English text below —

C’è un lungo intervallo di tempo tra la visione creatrice iniziale e il risultato finale; spesso passano anni.

Louise Bourgeois

E pensa a come l’ha ingannato la Prudenza,

a come se ne fidava sempre – che follia!

“Domani. Hai molto tempo” diceva la bugiarda

Kostantino Kavafis

Testo di Luca Berta —

Cosa succederà nel Capitolo V di Sposare la notte, dopo la filiazione dei primi quattro episodi non è dato a sapere. A Venezia ho partecipato a Spettri. Siamo partiti all’imbrunire, solcando le alghe tenui della Laguna. Non siamo ritornati al punto di partenza.

La coppia torinese che era in barca con me era un po’ infastidita – l’appartamento che avevano preso in affitto era molto più lontano dai Giardini da La Biennale, dove siamo sbarcati, era l’una di notte, dopo sette ora in barca faceva freddo. Io ho detto che probabilmente anche questo faceva parte della strategia di dislocazione di g. olmo stuppia: siamo abituati a pensare che quando prenotiamo la partecipazione a un’esperienza, ci vengono a prendere, ci portano in giro, e infine ci riportano nel luogo in cui siamo partiti. Lo credevo anch’io, pur senza averci pensato. E invece, ho detto agli altri, l’artista lavora proprio sul manipolare queste convinzioni precostituite. E ho aggiunto, in tono un po’ scherzoso, alla fine tutte le esperienze della vita sono così, non ti riconducono mai al nastro di partenza. Mi hanno risposto prevedibilmente con una battuta, l’equivalente bonario di mandarmi a quel paese per il tentativo di voler intellettualizzare una cosa insensata. Ma forse, a ripensarci il giorno dopo, la differenza tra un’escursione programmata e un’esperienza – una deriva, un cambiamento, una transizione, uno scivolamento, un ripensamento – sta proprio nel non richiudere l’anello.

Il punto di incontro alla fermata Celestia si apre sulla Laguna a nord di Venezia. Nel tardo pomeriggio di ottobre è uno specchio malva solcato dalle scie delle barche – dopo qualche attesa e il sequestro dei telefoni cellulari, anche delle nostre sei barche. Guardiamo l’orizzonte, e ci tastiamo le tasche nel riflesso di cercare l’apparecchio con cui immortalare in pixel quella bellezza transeunte.

L’artista conduce una patana a noleggio del cantiere di Andrea Lizzio a Cannaregio, l’ingegner Giovanni Cecconi la sua topa con issato un bastone avvolto di lucine led azzurre, le altre barche sono di ragazzi di Murano che l’artista ha ingaggiato, il capobanda è lo spavaldo e giovanissimo Mattia Rossini. Come prima tappa ci avviciniamo alla titanica struttura in metallo giallo attraccata appena fuori dal bacino dell’Arsenale: il jack-up (costo nominale 80 milioni) che serve a sollevare le paratie del MOSE per la manutenzione. Cecconi, che ha contribuito alla progettazione, spiega qualcosa, la nostra barca è un po’ distante, cita la pertica della palestra a scuola. Entriamo nel bacino dell’Arsenale e sostiamo sotto le scenografiche arcate delle Gaggiandre, davanti al Padiglione Italia che sprofonda nel crepuscolo. A ogni tappa l’ingegnere spiegherà qualcosa o l’artista declamerà qualcosa, ascoltiamo spesso senza aver compreso pienamente cosa, ricevendo le parole per ciò che sono. Non sappiamo dove andremo.

Nemmeno il giovanissimo conducente del piccolo motoscafo su cui sono salito sa quali sono le tappe (la verità è che non vi sono tappe, ma flussi e andirivieni), gli hanno detto inizialmente che doveva trasportare dei pacchi, poi dei turisti. Adesso ha capito che si tratta di “una cosa della Biennale”. Gli chiedo se ha visto Atlantide di Yuri Ancarani, all’inizio non afferra ma poi intuisce che si tratta del film che vede come protagonisti proprio dei ragazzi suoi coetanei delle isole della laguna, dominati dal demone del barchino e della velocità. Da un lato sembra orgoglioso che il gruppo cui appartiene sia il soggetto del film, dall’altro mostra una certa delusione, come se fosse stata un’occasione sprecata. Gli chiedo se pensa che il film racconti in modo fedele quel suo mondo. Dice di sì, ma che per la trama c’erano storie molto più coinvolgenti da scegliere. Ci leghiamo “a lai”, una barca affiancata all’altra, a una torretta di illuminazione davanti alla bocca di porto che collega la laguna al mare, a nord del Lido. La corrente in ingresso è vorticosa. Due metri al secondo. L’ingegnere spiega che il restringimento della bocca di porto creato dai lavori del MOSE ha accelerato le correnti, ma che i volumi d’acqua sono rimasti invariati. Ci parla delle turbolenze, che “stancano” l’acqua.

Ci saranno altre tappe, una davanti alla conca di navigazione del MOSE a Punta Sabbioni (uno stargate, come lo definisce qualcuno nella barca accanto, portale imponente di una chiusa contornato di luci a led), dove l’artista legge un passo di Spaesamento di Giorgio Vasta. Oppure l’estremità meridionale dell’isola di Sant’Erasmo, dove un cippo settecentesco indica l’antica congerminazione della Laguna, prima che le dighe foranee spostassero il mare tre chilometri più a sud-est (ancora viene scandita una poesia di Patrizia Cavalli). Per qualche motivo dopo gli interventi dell’ingegnere scoppia spontaneamente l’applauso, mentre le letture dell’artista lasciano noi partecipanti più disorientati, come se non sapessimo bene a cosa attaccare le parole che abbiamo ascoltato, ci manca un’àncora e forse proprio questo le parole tentavano di sussurrarci.

La tappa più suggestiva è quella su una lingua di sabbia che si estende per qualche decina di metri davanti alle bocche di porto. La costruzione dell’isola artificiale del MOSE ha cambiato il sistema di correnti, e lì da tre anni a questa parte ha preso ad accumularsi la sabbia. Le barche si adagiano sul fondale basso, ci togliamo le scarpe, immergiamo i piedi nel sorprendente tepore dell’acqua limpida, rischiarata dalla luna piena che ci accompagna inarcandosi sempre più alta sull’orizzonte. L’artista è fortunato ad aver scelto una notte così leopardiana. Dalla punta della lingua di sabbia (dinanzi il “Bacan”), dove il sedimento continua ad accumularsi insieme a piccoli detriti e alla soffice schiuma dei polisaccaridi metabolizzati dai cianobatteri, l’ingegnere ci conduce in avanti nello spazio e indietro nel tempo, a osservare come sulla sabbia accumulata uno, due o tre anni prima il meticoloso processo di biostrutturazione ha già creato un piccolo ecosistema in permanente evoluzione. Le piante sono basse, crescono su una sottile lente di acqua dolce trattenuta negli interstizi tra i granelli di sabbia. Chi di noi ha bisogno di urinare lo fa senza riparo, silhouettes scure ritagliate sul lembo più lontano della spiaggia. Chiedo all’ingegnere se quell’isolotto nato da poco abbia un nome. “Si chiama Metafora”, mi risponde. Applauso. Ed è proprio a Metafora che torneremo come tappa finale, in un andirivieni di barche e gorghi, nella più totale astratta lentezza.

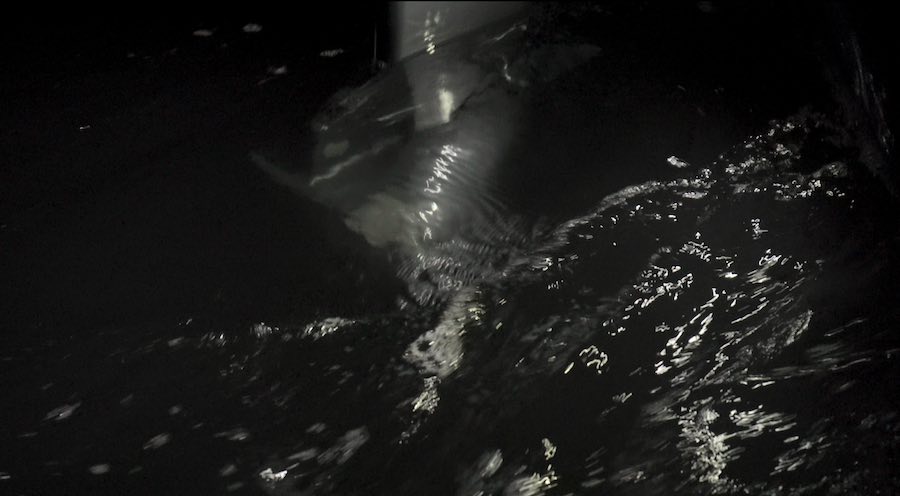

Le barche si allineano in formazione per tornare verso Venezia. Slanci e turgori, siamo tutt’uno col vespro della Luna, le isole martoriate dalla tecnica, la Laguna scippata ai suoi abitanti. Navighiamo e resistiamo. Il giovane conducente della mia barca è impaziente perché vorrebbe tornare in tempo per vedere i suoi amici, e sopporta a stento di procedere così lentamente (altra escamotage per invertire l’ossessione postfuturista, possessiva nei confronti delle acque della Laguna più estesa d’Europa). L’ingegnere, mentre stringe la manopola del suo fuoribordo, si passa il filo di luci led azzurre attorno al capo, come una corona. Offro agli altri della barca l’unica cosa che avevo portato da condividere, un pacco di cantucci senesi, li mangiamo tutti. Sposiamo la notte. Spettri.

Leggi

— Lucciole a Sacca San Mattia, Venezia, con g. olmo stuppia Ep. I

— Sposare la notte Ep. II – La Fabbrica di lucciole

— Sposare la notte – Ep. III | Cammino terzo

Marrying the night, episode IV. Spettri (Spectrum)

An account of the last episode of the quadraphonic “Sposare la notte long term project – Marrying the Night”, from the Venice Arsenal by the MOSE and San Nicoletto, touching , exploring the spaces that are still alive in Europe’s largest Lagoon.

There is a long time lag between the initial creative vision and the final result; often years go by.

Louise Bourgeois

And think how Prudence tricked him,

how he always trusted it – what madness!

“Tomorrow. You have plenty of time,” said the liar.

Kostantino Kavafis

Text by Luca Berta —

What’s the next Chapter after that crazy experience?

We did not return to our starting point. The couple from Turin who was on the boat with me was a bit annoyed – the flat they were renting was much further away from the Giardini della Biennale, where we disembarked, it was one o’clock in the morning, and after seven hours on the boat it was cold. I said that this was probably as well part of g. olmo stuppia’s dislocation strategy: we are used to thinking that when we book to participate in an experience, they pick us up, take us around, and finally bring us back to the place from where we left. I believe so too, without having really thought about it. And instead, I told the others, the artist works precisely on manipulating these pre-constituted beliefs. And in a little joking tone I added that in the end, all experiences in life are like that, they never lead you back to the starting tape. They responded predictably with a joke, the good-natured equivalent of telling me off for trying to intellectualize something nonsensical. But perhaps, looking back on it the next day, the difference between a planned excursion and an experience – a drift, a change, a transition, a slippage, an afterthought – lies precisely in not closing the loop.

The meeting point at the Celestia stop opens onto the Lagoon north of Venice. In the late October afternoon, it is a mauve mirror furrowed by the trails of boats – after some waiting and the confiscation of mobile phones, the wake of our six boats add up. We gaze at the horizon, feeling our pockets in the conditioned reflex of searching for the device with which to capture in pixel such transient beauty.

The artist drives a rented patana from Andrea Lizzio’s shipyard in Cannaregio, engineer Giovanni Cecconi his topa hoisted with a stick wrapped in blue LED lights, the other boats are by Murano boys hired by the artist, the ringleader is the swaggering young Mattia Rossini. As a first stop, we approach the titanic yellow metal structure docked just outside the Arsenale basin: the jack-up (nominal cost 80 million) used to raise the MOSE bulkheads for maintenance. Cecconi, who helped design the system of mobile dams that protects the city from extreme tides, explains something (our boat is a bit far away). He mentions the pole in the school gym. We enter the Arsenale basin and pause under the scenic arches of the Gaggiandre, in front of the Padiglione Italia that sinks into the twilight. At each stop the engineer will explain something, or the artist will declaim something, and we listen, at times without fully understanding, receiving the words for what they are. We do not know where we are going.

Not even the very young driver of the small speedboat on which I boarded knows the scheduled stops (the truth is that there are no stops, but ebbs and flows). He was initially told that he had to transport parcels, then tourists. Now he understands that it is “a Biennale thing”. I ask him if he has seen Atlantis by Yuri Ancarani. At first he doesn’t grasp, but then he realizes that it is the film starring boys of his own age from the islands in the lagoon, dominated by the demon of the barchino and of speed. Yes, he has seen it too.

On the one hand he seems proud that the group he belongs to is the subject of the film, on the other hand he shows some disappointment, as if it was a wasted opportunity. I ask him if he thinks the film faithfully portrays that world of his. He says yes, but that there were much more interesting stories to choose from for the plot. We tie up “a lai”, one boat alongside the other, to a lighting tower in front of the mouth of the harbor that connects the lagoon to the sea, north of the Lido. The incoming current is swirling. Two meters per second. The engineer explains that the narrowing of the harbor mouth caused by the works at the MOSE has accelerated the currents, but the water volumes remained the same. He tells us about the turbulence, which “tires out” the water.

There will be other stops, one in front of the MOSE navigation lock at Punta Sabbioni (a sort of stargate, as someone in the boat next to us defines it, an imposing portal of a sluice surrounded by LED lights), where the artist will excerpt a passage from Giorgio Vasta’s Spaesamento. Or the southern end of the island of Sant’Erasmo, where an eighteenth-century cippus indicates the ancient boundary of the lagoon, before the breakwaters moved the sea three kilometers further south-east (a poem by Patrizia Cavalli is still being recited). For some reason, applause spontaneously broke out after the engineer’s intervention, while the artist’s readings left us participants more disoriented, as if we did not quite know where to attach the words we had heard, we lacked an anchor: and perhaps this is precisely what the words were trying to whisper to us.

The most striking stop is on a tongue of sand that stretches for a few dozen meters in front of the harbor mouths. The construction of the MOSE artificial island has changed the current system, and sand has been accumulating there for the past three years. The boats settle on the shallow seabed, we take off our shoes, dip our feet into the surprising warmth of the clear water, illuminated by the full moon that accompanies us as it arches higher and higher over the horizon. The artist is lucky to have chosen such a Leopardi-like night. From the tip of the sand tongue (in front of the “Bacan”), where the sediment continues to stratify along with small debris and the soft foam of polysaccharides metabolized by cyanobacteria, the engineer leads us forward in space and back in time, to observe how on the sand accumulated one, two or three years earlier the meticulous process of bio-structuring has already created a small ecosystem in permanent evolution. The plants are low, growing on a thin lens of fresh water held in the interstices between the grains of sand. Those of us who need to urinate do so without hiding, dark silhouettes on the far strip of the beach. I ask the engineer if that newly born islet has a name. “It is called Metafora”, he replies. Applause. And precisely to Metafora we return as a final stop, in a coming and going of boats and whirlpools, in an abstract sluggishness.

The boats line up in formation to return towards Venice. We mingle with the moonlight, with the islands battered by technology, the lagoon robbed of its inhabitants. We sail and we resist, we exist. The young driver of my boat is impatient, because he would like to be back in time to see his friends, and he can hardly bear to proceed so slowly (another stratagem by the artist to reverse Lagoon kids about post-futurist, possessive obsession with the waters of Europe’s largest Lagoon). The “engineer”, while tightening the knob of his outboard, passes the string of blue LED lights around his head, like a crown. I offer the others on the boat the only thing I had brought to share, a pack of Sienese cantucci. We all eat them. We marry the night. Spettri.