English version below —

C’è qualcosa di ininterrotto nel modo in cui Tilda Swinton entra nelle immagini: non le interpreta, le attraversa. Ogni ruolo, ogni gesto, ogni frammento di voce sembra provenire da un altrove che non si chiude mai, una frontiera in perenne trasformazione. Ongoing — la grande mostra che l’EYE Filmmuseum di Amsterdam le dedica (sino all’8 Febbraio 2026) — non è una retrospettiva, né un omaggio: è un organismo in movimento, una camera d’ eco che respira insieme al cinema, alla performance, al sogno e alla memoria.

Il titolo stesso, Ongoing, racchiude la chiave dell’intero progetto: ciò che continua, che si prolunga, che non si arresta alla superficie di un film o alla conclusione di una scena. È un verbo che diventa stato, un participio che dice durata. Come ha dichiarato Swinton nel catalogo, “To go on, to keep making light — that’s the only way of living with cinema.” Il titolo, scelto da lei stessa, è quindi una dichiarazione di poetica e di resistenza: continuare a fare luce come unico modo di vivere il cinema. L’esposizione si offre come una costellazione di apparizioni e sparizioni, un montaggio che rinuncia alla linearità per farsi corrente.

L’EYE Filmmuseum, che si staglia come una scultura di luce sulla riva nord dell’IJ, è di per sé una dichiarazione di poetica. Progettato dallo studio viennese Delugan Meissl Associated Architects e inaugurato nel 2012, l’edificio è una geometria di piani obliqui, un corpo irregolare che riflette il cielo e l’acqua. Dalla Stazione Centrale di Amsterdam lo si raggiunge con un breve tragitto in traghetto: un attraversamento che è già preludio visivo, una soglia liquida tra la città e il suo doppio specchiato.

La missione del museo è quella di custodire e ripensare il cinema come patrimonio vivo — non solo conservazione, ma riattivazione delle immagini. L’EYE non è un mausoleo, ma una macchina respirante: proietta, restaura, produce, ospita artisti che mettono in discussione il confine tra film e installazione. Il suo archivio comprende oltre 54.000 titoli, dalle prime pellicole dei fratelli Lumière ai più recenti esperimenti digitali, in dialogo con una programmazione espositiva che unisce storia, ricerca e visione contemporanea. In questo luogo sospeso tra acqua e cielo, il cinema si rinnova come esperienza sensoriale totale: il luogo ideale, dunque, per ospitare Ongoing, una mostra che del movimento fa la propria condizione esistenziale.

Swinton — qui al tempo stesso soggetto e curatrice implicita, presenza e fantasma — ha collaborato direttamente con il team curatoriale dell’EYE (tra cui Jaap Guldemond, Simone van den Berg e Jennifer Lange), concependo con loro un ritratto espanso: un film disseminato nel museo, un autoritratto in movimento che si costruisce attraverso immagini, suoni e oggetti.

Appena si entra nello spazio, la percezione è quella di un archivio che si muove. Le proiezioni, i monitor, gli schermi sospesi non sono disposti secondo un percorso narrativo ma come un ritmo: il tempo dell’immagine si dilata, ritorna, cambia frequenza. Il percorso è articolato in cinque “respiri” tematici — non sezioni rigide ma onde di durata — che corrispondono ai momenti di una vita in immagini: nascita, corpo, legami, sopravvivenza e continuità. In un angolo, le fotografie di The Garden (1990) di Derek Jarman convivono con costumi di scena provenienti da Orlando (1992), mentre su una parete scorre la sequenza rallentata di Memoria (2021), di Apichatpong Weerasethakul, in cui la voce di Swinton sembra nascere dal suolo. Tutto vibra di un’energia silenziosa: una tensione tra presenza e dissoluzione, tra corpo e luce.

“Being an image means surviving yourself”, dice Swinton in una delle interviste che accompagnano la mostra. È la frase che potrebbe definire l’intero percorso: sopravvivere a se stessi, lasciare che l’immagine diventi ciò che resta quando il corpo non c’è più. Ongoing esplora proprio questo spazio sospeso: il momento in cui la rappresentazione smette di essere illusione e diventa materia viva, capace di incarnare l’invisibile. Nei testi scritti da Swinton per il catalogo, si legge di “un corpo che trattiene il cinema come un respiro” e di “un dialogo costante con i fantasmi che abitano la luce”. Si tratta di un cinema vibrante, che non rappresenta ma continua a pulsare.

L’EYE Filmmuseum — con la sua architettura bianca, obliqua, affacciata sull’acqua — sembra fatto apposta per questo dialogo. Le sale non chiudono ma aprono; non contengono, ma riverberano. La mostra, ideata in collaborazione con il museo e costruita come un viaggio attraverso decenni di cinema, è pensata come una proiezione continua della vita stessa. Ci sono fotografie, installazioni, materiali d’archivio, disegni, appunti, frammenti di costumi, ma anche nuove opere, inediti, performance registrate e lettere. Molti di questi materiali provengono da archivi internazionali — il British Film Institute, la Fondazione Prada e il Thailand Film Archive — e vengono esposti per la prima volta: segni di una genealogia affettiva che attraversa luoghi e tempi diversi. Ogni oggetto è un detrito luminoso, una scheggia di tempo.

Swinton non ha mai separato la vita dall’immagine: la sua filmografia — da Caravaggio (1986) a The Eternal Daughter (2022) — è un continuum di incarnazioni che si richiamano, si inseguono, si riscrivono. È in Jarman che si trova il principio di questa genealogia, il punto in cui il cinema diventa comunione e rito, un linguaggio collettivo che affonda nella terra e nella luce. Il loro incontro, avvenuto sul set di Caravaggio, fu l’inizio di una consonanza creativa che avrebbe segnato per sempre entrambi. Per Jarman, Swinton incarnava la possibilità di un cinema vivo, un corpo capace di attraversare il tempo e il genere, di rendere visibile ciò che non ha forma. Per lei, Jarman fu una rivelazione: l’artista che trasformò il set in un luogo sacro, un laboratorio di immagini e di libertà. Nei film successivi — The Last of England (1987), The Garden (1990), Edward II (1991), Wittgenstein (1993) — Swinton divenne una figura quasi liturgica: icona e spettro, angelo e testimone, corpo politico e mistico insieme. In Wittgenstein, il più mentale e siderale dei film di Jarman, Swinton non interpreta: pensa con il corpo. Nei panni di Lady Ottoline Morrell, entra nello spazio come un concetto vestito di colore, un’apparizione che disarticola la logica con la grazia. In quel vuoto scenico, sospeso tra aforisma e visione, la sua presenza è la figura del pensiero stesso — il gesto che illumina ciò che non si può dire. Ogni movimento diventa sillaba, ogni silenzio una fessura del linguaggio. È come se il suo corpo respirasse il pensiero di Wittgenstein, rendendolo visibile, trasportandolo oltre il confine del discorso. Lì dove la filosofia tace, lei appare: corpo di luce nell’ombra del concetto, immagine che pensa.

Jarman la definiva “the most luminous creature I’ve ever filmed”, intuendo in lei non un’interprete ma una presenza medianica, un volto che non appartiene al tempo. Swinton, a sua volta, ha sempre riconosciuto in lui il proprio mentore spirituale: “He showed me that cinema could be a home, a family, a faith.” Insieme costruirono un linguaggio comune, fatto di luce, poesia e dissidenza — un cinema queer e visionario che faceva dell’amore un atto di resistenza.

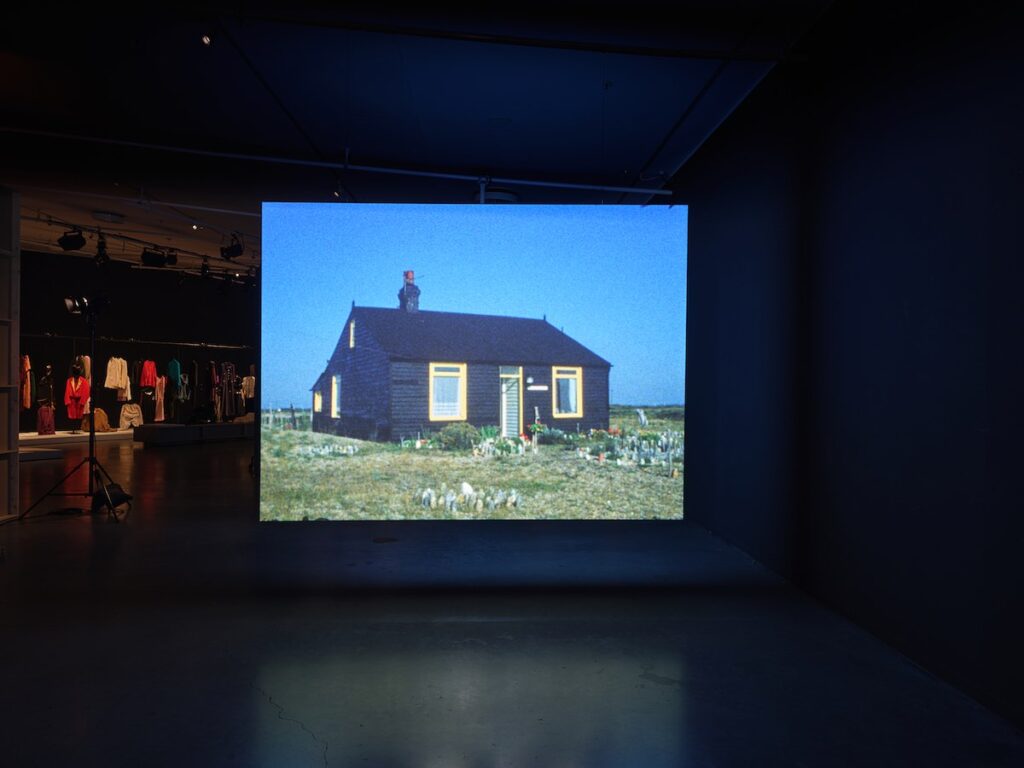

Nel giardino di Prospect Cottage a Dungeness, tra le piante di finocchio selvatico e le pietre disposte come reliquie, Swinton nel tempo ha continuato a tornare, come se lì si custodisse la sorgente di una luce ancora attiva. La mostra Ongoing raccoglie anche quella eredità: la fede di Jarman in un cinema vivo, vulnerabile, capace di rigenerarsi nel contatto con la realtà. In fondo, Swinton è la sua immagine postuma — la prosecuzione luminosa di un pensiero che non si è mai interrotto.

Dopo Jarman, è Luca Guadagnino la voce che più intimamente ha saputo risuonare con quella di Swinton. Il loro incontro, nato alla fine degli anni Novanta, non è solo un capitolo di film condivisi, ma una lunga conversazione sulla visione, sull’amore, sulla materia del tempo. Guadagnino non dirige Tilda: la ascolta. Tra loro il cinema si fa complicità silenziosa, un modo di pensare attraverso le immagini, di riconoscersi nei riflessi dell’altro.

In I Am Love (2009), il suo volto si apre come una ferita luminosa: un corpo che si fa linguaggio, dove il desiderio diventa forma e la forma, emozione. In A Bigger Splash (2015), la voce perduta è già memoria, un’eco che attraversa la luce del Mediterraneo come un fiato trattenuto. In Suspiria (2018), la metamorfosi si fa vertigine: tre presenze, tre enigmi che si cercano nello stesso corpo, tra magia e rivelazione.

Il loro legame non conosce ruoli né gerarchie. È un dialogo di fiducia e vertigine, di affinità più che di mestiere. Swinton ha detto di lui: “Luca is a brother, a friend, a filmmaker who dreams aloud.” Ma in quella frase c’è qualcosa di più: il riconoscimento di un’anima affine, capace di comprendere la fragilità come potenza, l’intimità come spazio politico.

Nel loro percorso comune, il cinema diventa luogo di confessione e di rinascita: non racconto, ma ascolto; non messa in scena, ma tempo condiviso. È in Guadagnino che Swinton trova la continuità di Jarman: lo stesso desiderio di un cinema che tocchi la pelle del mondo, che trasformi la luce in sentimento.

Ma in Ongoing si percepisce anche il dialogo con Apichatpong Weerasethakul, con Sally Potter, con Bong Joon-ho e con Joanna Hogg: una costellazione di registi che hanno fatto della sua presenza una forma di pensiero.

Ogni film è qui un atto di reincarnazione. In Orlando Swinton attraversa quattro secoli senza mai cambiare, rivelando che il genere è una finzione del tempo. In The Garden, è figura angelica e martire, corpo politico e sacro insieme. In Memoria, la sua voce è un suono sepolto, un richiamo alle radici della percezione. E in The Eternal Daughter, la sua doppia interpretazione — madre e figlia — diventa un confronto vertiginoso con la memoria e l’assenza. Ongoing restituisce tutto questo non come una somma di ruoli, ma come un’unica, infinita trasformazione.

In Memoria, il vedere diventa ascolto. Swinton non si muove: è il mondo che, intorno a lei, cambia respiro. Il suono che attraversa il film — unico, inspiegabile, terrestre — non chiede di essere capito, ma ricordato. È l’eco di qualcosa che accade sempre, anche quando tace.

Alla fine, Tilda non guarda più il mondo: lo ricorda.

E in quella memoria silenziosa, Ongoing trova la sua misura: l’immagine che non mostra, ma continua a vivere, anche dopo la fine. Come suggerisce la sezione “Sounding the Image” del catalogo, il suono diventa la materia scultorea della visione: una presenza tattile che scolpisce lo spazio e prolunga il corpo oltre la visibilità. È come se il suono fosse la nuova forma della luce, un corpo invisibile che continua a vibrare quando tutto tace.

Il visitatore attraversa le sale come chi entra in un sogno che non finisce. L’illuminazione è tenue, quasi lunare; il suono arriva da più direzioni, ma sembra provenire da dentro le immagini stesse. Ci sono voci, frammenti di dialoghi, sospiri, risate, musiche. Tutto si fonde in un continuum sensoriale che trascende la distinzione tra visione e ascolto. È un cinema che non si guarda: si vive. Il pubblico diventa co-performer dell’immagine, come scrive il team dell’EYE: non spettatore ma partecipe, corpo in ascolto. Ogni passo, ogni sosta è una forma di montaggio, un gesto che completa l’opera.

La mostra si apre con una proiezione multipla: The Maybe, la performance del 1995 in cui Swinton dorme, esposta in una teca di vetro alla Serpentine Gallery di Londra. Quel gesto — il corpo dell’attrice che si offre come reliquia vivente — diventa qui il prologo di un percorso sulla durata, sul tempo come presenza assoluta. Dormire davanti allo sguardo altrui: ecco la forma più radicale dell’essere immagine. Da quel corpo immobile parte tutto, come un battito che si dirama in decine di forme. Nel catalogo, Swinton definisce questa performance “the seed of Ongoing”: il seme da cui tutto germina, la promessa che il corpo può essere immagine senza cessare di vivere.

Più avanti, un’installazione sonora riunisce estratti di film, interviste, improvvisazioni vocali. Le parole si intrecciano come in una partitura: “Who are you when the camera sleeps?”, “What is left when the light goes off?”. Sono domande che attraversano tutta la mostra, senza trovare risposta. L’immagine, qui, non è rappresentazione ma esperienza del limite: la possibilità di restare in ascolto dell’invisibile.

C’è anche un’attenzione filologica e affettiva per il passato. I materiali d’archivio provenienti dai film di Jarman — Caravaggio, The Last of England, Edward II — convivono con documenti più recenti: appunti di regia di Guadagnino, disegni di costumi di Sandy Powell, fotografie di Juergen Teller. Ma non si tratta di memorabilia: sono reperti che costruiscono un tempo emotivo, una stratigrafia del vedere. Ogni dettaglio — un guanto, una parrucca, una pagina dattiloscritta — diventa un frammento di autobiografia visiva, come se il cinema potesse farsi corpo anche attraverso le sue tracce materiali.

L’effetto complessivo è quello di una liturgia sospesa: Ongoing non celebra, ma riaccende. La mostra non guarda al passato come a una forma di nostalgia, bensì come a un deposito di possibilità. Ogni immagine è un corpo che si rinnova, ogni proiezione un gesto che ricomincia. La parola “ongoing” diventa così una dichiarazione di poetica: l’arte come stato permanente di metamorfosi, la visione come atto ininterrotto di nascita.

Swinton attraversa il cinema come un principio di trasformazione. Per lei, recitare è un atto di attraversamento. Non costruisce un personaggio, ma uno stato di trasparenza. Ogni volta che appare, lascia che la luce la attraversi come un corpo d’acqua: non esprime, accoglie. “Actors are mediums, not mirrors,” ha detto una volta — e in quella frase si concentra tutta la sua poetica. L’attore non riproduce il mondo, lo lascia passare attraverso di sé. È una pratica di ascolto, una forma di respirazione condivisa con la macchina da presa, in cui il gesto diventa pensiero e il tempo materia sensibile. La sua recitazione non comunica: vibra. È una filosofia incarnata della trasformazione, dove ogni corpo è un ponte verso l’invisibile. Ogni film in cui appare sembra nascere da una domanda sul corpo: che cosa significa essere visibili? Che cosa resta, quando la visione cede alla luce? Il suo volto, spesso definito “androgino”, non è mai neutro: è un territorio di passaggio, un luogo dove il genere, il tempo e l’identità si disgregano per rinascere in altre forme. In questo senso, Ongoing è una mostra sulla metamorfosi intesa come condizione ontologica: non un processo che si conclude, ma un ritmo che continua a pulsare, anche quando lo schermo si spegne.

Ciò che anche colpisce, nelle sale dell’EYE, è la continuità tra le immagini e i corpi che le abitano. Swinton non si limita a impersonare, ma costruisce un modo di esistere nell’immagine. Non è un caso che la mostra includa fotografie di The Maybe accanto ai frammenti video di The Seasons in Quincy: Four Portraits of John Berger (2016). In entrambi i casi, l’immagine non serve a raccontare ma a creare uno spazio condiviso: un campo magnetico tra chi guarda e chi è guardato. Come Berger, Swinton sembra credere che “vedere” sia un atto etico, una forma di coabitazione tra soggetti e cose.

Il tema della metamorfosi attraversa anche la relazione con il tempo. Ongoing dissolve ogni cronologia: Caravaggio convive con The Eternal Daughter, I Am Love con Memoria. Il tempo non è più una linea ma un cerchio, un battito che torna. Questo movimento ricorda la concezione di Jarman, per il quale il cinema era “a living garden”, un giardino vivo dove le immagini crescono e muoiono come piante. Swinton riprende quel giardino e lo trasforma in paesaggio interiore: la durata diventa una forma d’ascolto, la pellicola un corpo che respira piano.

Nella sezione centrale della mostra, una grande installazione multicanale intitolata The Line of Flight intreccia frammenti provenienti da film e video sperimentali: il volto di Swinton che si volge verso la luce in Edward II, un primo piano di The Deep End, un’inquadratura sfocata da Only Lovers Left Alive. Le immagini si sovrappongono come in una sinfonia visiva, mentre la sua voce, fuori campo, recita un testo tratto da The Garden: “The body is a prayer written on water.” È in questo intreccio che emerge la sua poetica: il corpo come superficie attraversata dal tempo, come luogo dove la luce lascia tracce di sé.

Il dialogo con il cinema queer di Jarman è il cuore pulsante della mostra. Ongoing non lo cita come memoria, ma come eredità attiva. Il film The Garden (1990), in cui Swinton interpreta una figura angelica e martire, è riproposto in una sala isolata, immersa in una luce azzurra. Attorno, schermi più piccoli mostrano materiali d’archivio, lettere e fotografie del regista. Qui l’immagine di Jarman non è reliquia, ma sorgente: la testimonianza di un cinema nato dalla marginalità, capace di unire desiderio e politica, eros e trascendenza. Swinton ne raccoglie la fiaccola, trasformando la vulnerabilità in linguaggio.

Nel dialogo con Jarman c’è qualcosa di profondamente rituale. Entrambi concepiscono il cinema come un atto comunitario, un rito condiviso che ha la forza di guarire. Per Jarman, la pellicola era un luogo di resistenza contro la normalizzazione; per Swinton, è un modo di abitare poeticamente il mondo. Ongoing riprende questa tensione e la amplifica: l’immagine diventa spazio di empatia, un luogo di attraversamento, in cui le differenze non vengono cancellate ma accolte. È un cinema che non esclude, ma include: che non definisce, ma domanda.

Nei materiali dedicati a Orlando, l’energia di questo pensiero è tangibile. La regia di Sally Potter, nel 1992, aveva trasformato il romanzo di Virginia Woolf in un inno alla libertà dei corpi e del tempo. Swinton, che attraversa quattro secoli mutando genere ma non identità, incarna la possibilità di una continuità oltre la biologia. Nel percorso di Ongoing, questo film torna come una sorgente di luce: una dichiarazione di poetica e di esistenza. “We change, yet we remain the same,” recita Orlando davanti allo specchio — ed è come se quella frase appartenesse all’intera mostra.

In Orlando, Swinton non attraversa un ruolo: si lascia attraversare dal tempo. Orlando, nato dalla pagina e proiettato sul tempo, trova nel corpo di Tilda la tessitura sottile di un’esistenza sospesa — un filo tra ieri e domani che non si spezza, e insieme non si sazia del presente. Nel suo sguardo c’è quiete e domanda allo stesso momento: come se guardasse il mondo dal bordo di un lago silente e lo riconoscesse per la prima volta.

Il genere, il secolo, il paesaggio: tutto si muove e muta, eppure lei resta. Non è la stasi, è la resistenza viva: un corpo che accoglie ogni forma, ogni epoca, senza perdere la propria risonanza. Quando Orlando si sveglia donna, non dichiara una metamorfosi: suggerisce un ritorno a sé — “Same person. No difference at all.” È in quella frase, semplice proprio come un respiro sommesso, che il tempo si inclina e ricomincia.

Potter la lascia camminare tra giardini, saloni, deserti come se fossero stanze d’attesa. E Tilda le attraversa come un sogno che non sa di essere sogno: il paesaggio diventa eco del suo silenzio, i passi un battito lieve nella grande volata del secolo. Il suo corpo è grammatica di spazio, il suo silenzio una forma di lingua.

Orlando non è solo il film della libertà: è il film della durata. E Swinton ne è la prima eco — immagine che non svanisce quando la luce si spegne, ma che resta nell’aria, vibrante. Nel suo sorriso finale, il cinema riconosce la propria soglia respirante: non più racconto, ma presenza. E la visione, quel brivido sottile, si fa casa.

Ma Ongoing non è solo una genealogia queer: è anche una riflessione sull’immagine come promessa di sopravvivenza. In una delle sale finali, un video intitolato Afterlight (2024) — realizzato con il figlio Xavier Swinton Byrne — mostra un corpo immerso nell’acqua, sospeso tra luce e buio. La figura si muove lentamente, come se stesse cercando di tornare alla superficie. È un’immagine di resurrezione, ma anche di memoria: una figura che prolunga la vita oltre la sua fine.

Il curatore dell’EYE ha parlato di Ongoing come di “una mostra che respira”: un’esposizione che non si limita a mostrare, ma che costruisce un’esperienza temporale. Lo spettatore è invitato a muoversi liberamente, a sedersi, ad ascoltare, a sostare. Non c’è un inizio né una fine. È una visione in loop, come se il cinema, una volta liberato dalla linearità, potesse diventare spazio mentale puro.

E in effetti, ciò che colpisce è proprio la capacità della mostra di fondere l’intimità con la vastità. Le immagini, anche quelle tratte dai film più noti, perdono la loro funzione narrativa per diventare presenze autonome. Il volto di Swinton in Memoria, che ascolta un suono misterioso provenire dalla terra, si trasforma in un’icona del sentire contemporaneo: un atto di ascolto che è insieme personale e cosmico. La mostra sembra chiederci di ritrovare la lentezza dello sguardo, di ascoltare il fiato dell’immagine.

L’impressione finale è quella di una cerimonia lenta, un atto di dedizione alla fragilità delle immagini. Ongoing ci ricorda che ogni fotogramma è un corpo che ha amato, ogni proiezione un gesto che permane. Tilda Swinton non interpreta la vita: la prolunga, la traduce in presenza luminosa. “Essere un’immagine significa sopravvivere a se stessi” — e in questa sopravvivenza c’è tutta la poesia del suo cinema.

Come scriveva Virginia Woolf: “The future is dark, which is the best thing the future can be.” Ongoing abita proprio quella oscurità feconda: il luogo dove la luce del cinema continua, incessante, a nascere. Quando l’immagine svanisce, Tilda resta. Non più corpo, non più figura — soltanto un’eco di luce che attraversa il tempo e lo lascia tremare.

Non chiede di essere ricordata. È nel modo in cui l’aria cambia, nel bianco che rimane sugli schermi dopo la fine. In lei il cinema non rappresenta: ascolta. Si ritira, come un fiato che non ha bisogno di voce.

Tilda vive quel punto in cui la visione si spegne e comincia il vedere. Ogni film è solo un pretesto per continuare a sognare.

Cover: Still from Luca Guadagnino’s Camaraderie, 2025. Commissioned by Eye Filmmuseum, co-produced by Onassis Stegi. © Luca Guadagnino

TILDA SWINTON. ONGOING | EYE Filmmuseum, Amsterdam

Text by Rita Selvaggio —

There is something unbroken in the way Tilda Swinton enters images: she does not interpret them, she crosses through them. Every role, every gesture, every fragment of voice seems to come from an elsewhere that never closes, a frontier in perpetual transformation. Ongoing — the major exhibition dedicated to her by the EYE Filmmuseum in Amsterdam (on view until 8 February 2026) — is neither a retrospective nor an homage: it is a living organism, an echo chamber that breathes with cinema, performance, dream, and memory.

The title itself, Ongoing, contains the key to the entire project: that which continues, extends, refuses to stop at the surface of a film or at the end of a scene. It is a verb turned into a state of being, a participle that speaks of duration. As Swinton writes in the catalogue, “To go on, to keep making light — that’s the only way of living with cinema.” The title, chosen by her, is thus a statement of poetics and resistance: to keep making light as the only way to live with cinema. The exhibition unfolds as a constellation of appearances and disappearances, a montage that renounces linearity to become a current.

The EYE Filmmuseum itself — rising like a sculpture of light on the northern bank of the IJ — is a declaration of poetics. Designed by Delugan Meissl Associated Architects and inaugurated in 2012, the building is a geometry of oblique planes, an irregular body reflecting sky and water. From Amsterdam Central Station it is reached by a brief ferry ride: a passage that is already a visual prelude, a liquid threshold between the city and its mirrored double.

The museum’s mission is to preserve and rethink cinema as a living heritage — not only conservation, but reactivation of images. The EYE is no mausoleum, but a breathing machine: it screens, restores, produces, and hosts artists who question the boundary between film and installation. Its archive holds more than 54,000 titles, from the earliest Lumière reels to the most recent digital experiments, in dialogue with an exhibition programme that weaves together history, research, and contemporary vision.

Suspended between water and sky, the EYE renews cinema as a total sensory experience — the ideal place, then, to host Ongoing, a project that turns movement into its existential condition.

Swinton — here both subject and implicit curator, presence and phantom — has collaborated directly with the EYE’s curatorial team (including Jaap Guldemond, Simone van den Berg, and Jennifer Lange), conceiving with them an expanded portrait: a film disseminated through the museum, a self-portrait in motion built from images, sounds, and objects.

Upon entering the space, one senses an archive in motion. Projections, monitors, suspended screens are arranged not as a narrative path but as a rhythm: the time of the image stretches, returns, changes frequency. The layout unfolds in five thematic “breaths” — not rigid sections but waves of duration — corresponding to moments in a life of images: birth, body, bonds, survival, and continuity. In one corner, photographs from Derek Jarman’s The Garden (1990) coexist with costumes from Orlando (1992), while on a wall runs the slowed sequence from Memoria (2021) by Apichatpong Weerasethakul, where Swinton’s voice seems to rise from the soil itself. Everything vibrates with silent energy: a tension between presence and dissolution, between body and light.

“Being an image means surviving yourself,” says Swinton in one of the interviews accompanying the exhibition. It is a phrase that could define the entire journey: to survive oneself, to let the image become what remains when the body is no longer there. Ongoing inhabits precisely this suspended space — the moment when representation ceases to be illusion and becomes living matter, capable of embodying the invisible.

In the texts Swinton wrote for the catalogue, she speaks of “a body that holds cinema like a breath” and of “a constant dialogue with the ghosts that dwell in light.” It is a cinema that vibrates rather than represents — a cinema that keeps on pulsing.

The EYE Filmmuseum — with its white, oblique architecture leaning over the water — seems made for such a dialogue. The galleries do not close but open; they do not contain, they reverberate. Conceived in collaboration with the museum and structured as a journey through decades of cinema, the exhibition unfolds like a continuous projection of life itself. There are photographs, installations, archival materials, drawings, notes, fragments of costumes, as well as new works, previously unseen pieces, recorded performances, and letters. Many of these materials come from international archives — the British Film Institute, Fondazione Prada, and the Thailand Film Archive — and are shown for the first time: traces of an emotional genealogy that spans places and times. Each object is a luminous remnant, a shard of time.

Swinton has never separated life from image. Her filmography — from Caravaggio (1986) to The Eternal Daughter (2022) — forms a continuum of incarnations that echo, pursue, and rewrite one another. At its origin lies Derek Jarman: the moment when cinema becomes communion and rite, a collective language rooted in earth and light. Their encounter on the set of Caravaggio marked the beginning of a creative consonance that would define them both. For Jarman, Swinton embodied the possibility of a living cinema — a body able to move through time and gender, to make visible what has no form. For her, Jarman was a revelation: the artist who transformed the set into a sacred space, a laboratory of images and freedom.

In the films that followed — The Last of England (1987), The Garden (1990), Edward II (1991), Wittgenstein (1993) — Swinton became an almost liturgical figure: icon and spectre, angel and witness, political and mystical body at once. In Wittgenstein, the most cerebral and sidereal of Jarman’s films, Swinton does not act — she thinks with the body. As Lady Ottoline Morrell, she enters space like a concept dressed in colour, an apparition that unravels logic through grace. In that scenographic void, suspended between aphorism and vision, her presence becomes the figure of thought itself — the gesture that illuminates what cannot be said. Each movement turns into a syllable; each silence, a fissure in language. It is as if her body were breathing Wittgenstein’s thought, making it visible, carrying it beyond the frontier of discourse. Where philosophy falls silent, she appears: a body of light in the shadow of the concept, an image that thinks.

Jarman called her “the most luminous creature I’ve ever filmed,” sensing in her not an actress but a medium, a face unbound by time. Swinton, in turn, has always recognised him as her spiritual mentor: “He showed me that cinema could be a home, a family, a faith.” Together they built a shared language of light, poetry, and dissidence — a queer and visionary cinema that made love an act of resistance.

In the garden of Prospect Cottage in Dungeness, among wild fennel and stones arranged like relics, Swinton has kept returning over the years — as if the source of an unextinguished light were still guarded there. Ongoing gathers that legacy too: Jarman’s faith in a cinema that is alive, vulnerable, capable of regenerating itself through contact with reality. In many ways, Swinton is his posthumous image — the luminous continuation of a thought that never ceased.

After Jarman, it is Luca Guadagnino whose voice has most intimately resonated with Swinton’s. Their encounter, at the end of the 1990s, was not merely a chapter of shared films but a long conversation about vision, love, and the substance of time. Guadagnino does not direct Tilda: he listens to her. Between them, cinema becomes a silent complicity — a way of thinking through images, of recognising oneself in another’s reflection.

In I Am Love (2009), her face opens like a luminous wound: a body becoming language, where desire turns to form and form to emotion. In A Bigger Splash (2015), the lost voice is already memory — an echo crossing the Mediterranean light like a held breath. In Suspiria (2018), metamorphosis becomes vertigo: three presences, three enigmas seeking one another within the same body, between magic and revelation.

Their bond knows neither hierarchy nor role. It is a dialogue of trust and vertigo, of affinity more than craft. Swinton has said of him: “Luca is a brother, a friend, a filmmaker who dreams aloud.” But in that sentence lies something more — the recognition of a kindred soul, one who understands fragility as power and intimacy as a political space.

In their shared path, cinema becomes a place of confession and rebirth: not narration but listening; not mise-en-scène but shared time. In Guadagnino, Swinton finds the continuity of Jarman — the same longing for a cinema that touches the skin of the world, that transforms light into feeling.

Yet Ongoing also reveals her dialogue with Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Sally Potter, Bong Joon-ho, and Joanna Hogg — a constellation of filmmakers who have made her presence a mode of thought.

Each film here is an act of reincarnation. In Orlando, Swinton traverses four centuries without ever changing, revealing that gender itself is a fiction of time. In The Garden, she is both angelic and martyred figure — a political and sacred body at once. In Memoria, her voice is a buried sound, a summons to the roots of perception. And in The Eternal Daughter, her double role — mother and daughter — becomes a vertiginous confrontation with memory and absence. Ongoing restores all this not as an accumulation of roles, but as a single, infinite transformation.

In Memoria, seeing turns into listening. Swinton does not move; it is the world around her that alters its breath. The sound that traverses the film — singular, inexplicable, earthly — does not ask to be understood but remembered. It is the echo of something that happens always, even when it falls silent.

In the end, Tilda no longer looks at the world — she remembers it.

And in that silent memory, Ongoing finds its measure: the image that does not show, but continues to live, even after the end. As suggested by the catalogue section “Sounding the Image,” sound becomes the sculptural matter of vision — a tactile presence that carves space and extends the body beyond visibility. It is as if sound were the new form of light: an invisible body that keeps vibrating when everything else falls silent.

The visitor moves through the galleries as one might enter a dream that never ends. The light is dim, almost lunar; the sound comes from several directions, yet seems to rise from within the images themselves. Voices, fragments of dialogue, sighs, laughter, music — everything fuses into a sensorial continuum that transcends the distinction between seeing and hearing. This is a cinema not to be watched but lived. As the EYE curatorial team writes, the public becomes a co-performer of the image: not a spectator but a participant, a body in listening. Every step, every pause is a form of montage, a gesture completing the work.

The exhibition opens with a multi-screen projection: The Maybe, the 1995 performance in which Swinton sleeps inside a glass case at London’s Serpentine Gallery. That gesture — the actress’s body offered as a living relic — becomes here the prologue to a journey through duration, through time as absolute presence. To sleep before another’s gaze: the most radical form of being an image. From that still body, everything begins, like a heartbeat spreading into a hundred forms. In the catalogue, Swinton calls this performance “the seed of Ongoing” — the seed from which everything germinates, the promise that the body can be image without ceasing to live.

Further on, a sound installation gathers excerpts from films, interviews, and vocal improvisations. Words intertwine like a score: “Who are you when the camera sleeps?” — “What is left when the light goes off?” These questions traverse the entire exhibition without ever finding an answer. Here, the image is not representation but an experience of the threshold — the possibility of remaining in listening to the invisible.

There is also a philological and emotional care for the past. Archival materials from Jarman’s films — Caravaggio, The Last of England, Edward II — coexist with more recent documents: Guadagnino’s directing notes, Sandy Powell’s costume sketches, Juergen Teller’s photographs. But these are not memorabilia: they are relics that compose an emotional temporality, a stratigraphy of seeing. Each detail — a glove, a wig, a typewritten page — becomes a fragment of visual autobiography, as if cinema could become embodied even through its material traces.

The overall impression is that of a suspended liturgy: Ongoing does not commemorate, it rekindles. The exhibition does not regard the past as nostalgia, but as a reservoir of possibilities. Every image is a body renewed, every projection a gesture beginning anew. The very word ongoing thus becomes a declaration of poetics: art as a permanent state of metamorphosis, vision as an unbroken act of birth.

Swinton moves through cinema as a principle of transformation. For her, acting is an act of crossing. She does not construct a character but a state of transparency. Each time she appears, she lets light pass through her like through water: she does not express, she receives. “Actors are mediums, not mirrors,” she once said — and in that sentence lies her entire poetics. The actor does not reproduce the world but lets it pass through. It is a practice of listening, a form of shared respiration with the camera, in which gesture becomes thought and time, tangible matter. Her acting does not communicate — it vibrates. It is an embodied philosophy of transformation, where every body is a bridge toward the invisible.

Every film in which she appears seems to arise from a question about the body: what does it mean to be visible? What remains when vision gives way to light? Her face — often described as “androgynous” — is never neutral: it is a threshold, a terrain where gender, time, and identity disintegrate only to be reborn in other forms. In this sense, Ongoing is an exhibition about metamorphosis as an ontological condition: not a process that concludes, but a rhythm that continues to pulse, even when the screen goes dark.

What also strikes the viewer within the EYE’s galleries is the continuity between images and the bodies that inhabit them. Swinton does not merely embody, she invents a way of existing within the image. It is no coincidence that the exhibition places photographs from The Maybe beside video fragments from The Seasons in Quincy: Four Portraits of John Berger (2016). In both, the image serves not to narrate but to create a shared space — a magnetic field between the seer and the seen. Like Berger, Swinton seems to believe that to see is an ethical act, a form of cohabitation between subjects and things.

The theme of metamorphosis also informs her relation to time. Ongoing dissolves all chronology: Caravaggio coexists with The Eternal Daughter, I Am Love with Memoria. Time is no longer a line but a circle, a heartbeat returning. This movement recalls Jarman’s idea of cinema as “a living garden,” a fertile space where images grow and wither like plants. Swinton inherits that garden and transforms it into an inner landscape: duration becomes a mode of listening, film a body breathing slowly.

At the centre of the exhibition, a large multi-channel installation titled The Line of Flight weaves together fragments from films and experimental videos: Swinton’s face turning toward the light in Edward II, a close-up from The Deep End, a blurred shot from Only Lovers Left Alive. The images overlap like a visual symphony, while her voice, off-screen, recites a line from The Garden: “The body is a prayer written on water.” Within this weave, her poetics emerges clearly — the body as a surface traversed by time, as the place where light leaves its trace.

The dialogue with Jarman’s queer cinema is the exhibition’s beating heart. Ongoing does not cite him as memory but as active legacy. The Garden (1990), in which Swinton plays an angelic and martyred figure, is presented in an isolated room bathed in blue light. Around it, smaller screens display archival materials, letters, and photographs by the filmmaker. Here Jarman’s image is no relic but a source: the testimony of a cinema born from marginality, able to unite desire and politics, eros and transcendence. Swinton carries that torch forward, transforming vulnerability into language.

There is something profoundly ritual in Swinton’s dialogue with Jarman. Both conceive cinema as a communal act, a shared rite with the power to heal. For Jarman, film was a site of resistance against normalisation; for Swinton, it is a way of inhabiting the world poetically. Ongoing takes up that tension and amplifies it: the image becomes a space of empathy, a site of passage where differences are not erased but embraced. It is a cinema that does not exclude but includes — that does not define, but asks.

In the materials dedicated to Orlando, the energy of this thought is tangible. In 1992, under Sally Potter’s direction, Virginia Woolf’s novel was transformed into a hymn to the freedom of bodies and of time. Swinton, who traverses four centuries changing gender but not identity, embodies the possibility of a continuity beyond biology. Within Ongoing, this film returns as a source of light — a declaration of poetics and of existence. “We change, yet we remain the same,” Orlando says before the mirror — and it is as though that phrase belonged to the entire exhibition.

In Orlando, Swinton does not move through a role; she lets time move through her. Orlando, born from the page and projected into time, finds in Tilda’s body the subtle weave of a suspended existence — a thread between yesterday and tomorrow that never breaks and never tires of the present. In her gaze there is both stillness and questioning: as though she were looking at the world from the edge of a silent lake, recognising it for the first time.

Gender, century, landscape — all shift and mutate, yet she remains. It is not stasis but living resistance: a body that receives every form, every era, without losing its resonance. When Orlando wakes as a woman, she does not proclaim metamorphosis; she suggests a return to self — “Same person. No difference at all.” In that line, simple as a quiet breath, time bends and begins again.

Potter lets her wander through gardens, halls, deserts as though through waiting rooms. And Tilda moves among them like a dream unaware of itself: the landscape becomes an echo of her silence, her steps a faint pulse in the long sweep of a century. Her body is a grammar of space; her silence, a form of language.

Orlando is not only a film of freedom; it is a film of duration. And Swinton is its first echo — an image that does not fade when the light goes out but lingers in the air, trembling. In her final smile, cinema recognises its own breathing threshold: no longer story, but presence. And vision — that subtle shiver — becomes home.

Yet Ongoing is not only a queer genealogy; it is also a reflection on the image as a promise of survival. In one of the final rooms, a video titled Afterlight (2024) — made with her son Xavier Swinton Byrne — shows a body immersed in water, suspended between light and darkness. The figure moves slowly, as if trying to return to the surface. It is an image of resurrection, but also of memory — a figure extending life beyond its end.

The EYE curator described Ongoing as “an exhibition that breathes”: a presentation that does not simply show, but constructs a temporal experience. The viewer is invited to move freely, to sit, to listen, to linger. There is no beginning and no end — a vision on a loop, as if cinema, once freed from linearity, could become pure mental space.

Indeed, what strikes most is the exhibition’s ability to fuse intimacy with vastness. The images, even those from Swinton’s most recognisable films, lose their narrative function to become autonomous presences. Her face in Memoria, listening to a mysterious sound rising from the earth, becomes an icon of contemporary sensibility — an act of listening both personal and cosmic. The exhibition seems to ask us to recover the slowness of the gaze, to listen to the breath of the image.

The final impression is that of a slow ceremony, an act of devotion to the fragility of images. Ongoing reminds us that every frame is a body that has loved, every projection a gesture that endures. Tilda Swinton does not interpret life; she extends it, translating it into luminous presence. “Being an image means surviving yourself” — and in that survival lies the poetry of her cinema.

As Virginia Woolf wrote, “The future is dark, which is the best thing the future can be.” Ongoing inhabits that fertile darkness — the place where the light of cinema continues, incessantly, to be born. When the image fades, Tilda remains. No longer body, no longer figure — only an echo of light crossing time and making it tremble.

She does not ask to be remembered. She exists in the way the air changes, in the white that lingers on the screen after the end. In her, cinema does not represent — it listens. It withdraws, like a breath that needs no voice.

Tilda inhabits that point where vision dies and seeing begins. Every film is merely a pretext to keep on dreaming.

Cover: Still from Luca Guadagnino’s Camaraderie, 2025. Commissioned by Eye Filmmuseum, co-produced by Onassis Stegi. © Luca Guadagnino