English version below —

La ciudad de México no es un caos: es el orden del desorden, la legalidad de la confusión, la forma del desconcierto

(Carlos Monsiváis, Los rituales del caos, México, Ediciones Era, 1995, p. 14)

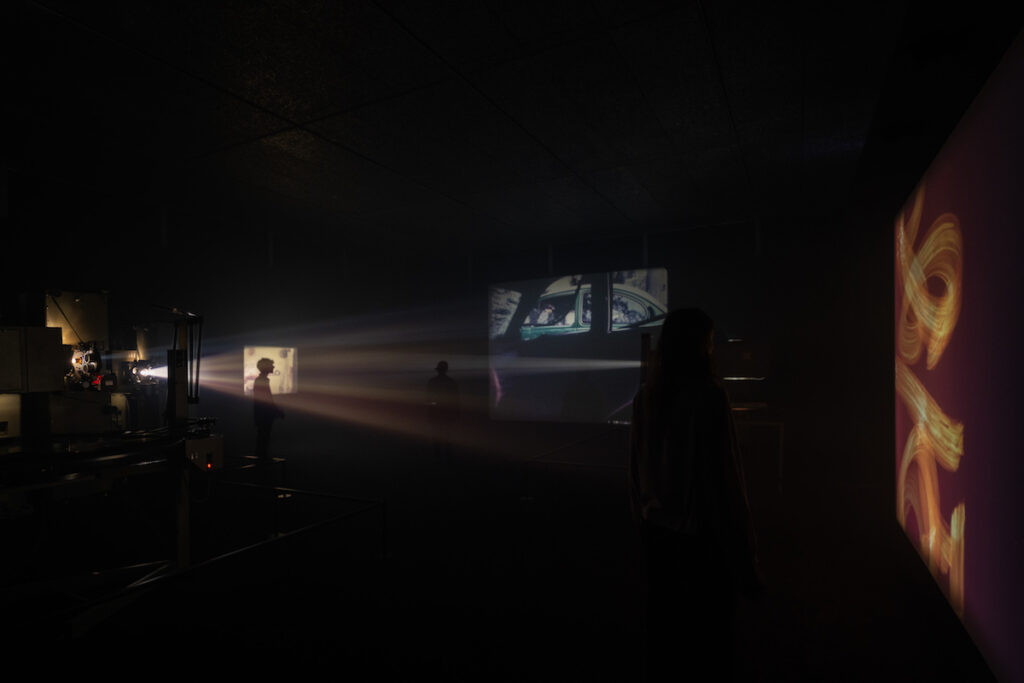

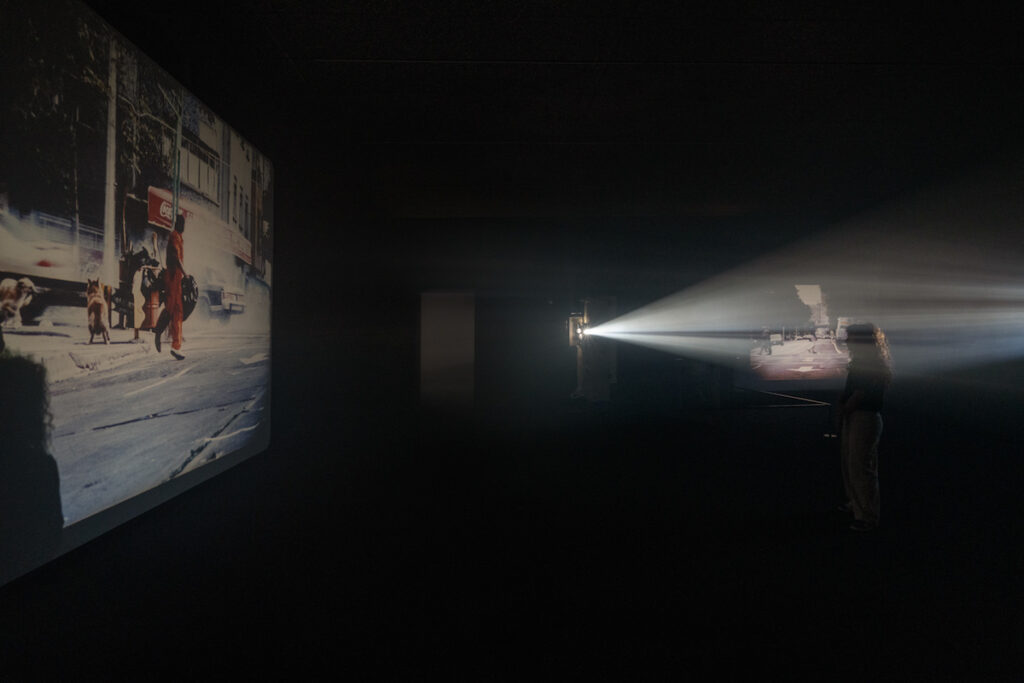

C’è un momento, entrando nel buio del Podium, in cui il cinema smette di essere finestra e torna a essere macchina. Il respiro dei proiettori analogici, il loro ronzio regolare, il cono di luce che taglia la polvere: tutto concorre a ricordarci che un’immagine in movimento è prima di tutto una materia che resiste. In Sueño Perro: Instalación Celuloide, mostra multisensoriale concepita da Alejandro G. Iñárritu per Fondazione Prada in occasione del venticinquesimo anniversario di Amores Perros (2000), il regista messicano riapre il corpo del suo film e ne mostra la muscolatura: i legamenti del montaggio, i tendini della durata, le cicatrici della copia di lavoro. Non c’è più la protezione della trama: al suo posto, un paesaggio di resti che chiede di essere attraversato con il corpo, non solo con lo sguardo.

Il punto di partenza è noto e insieme sorprendente: oltre trecento chilometri di pellicola scartata, corrispondenti a sedici milioni di fotogrammi, rimasta per venticinque anni negli archivi cinematografici dell’Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM). Ora, grazie a un lavoro di archeologia visiva e sonora, Iñárritu li riassembla in un dispositivo ambientale che traduce il film in città. Le sequenze non “raccontano” più: respirano; tornano a essere eventi di luce e suono che si offrono per prossimità, rima, cortocircuito. Laddove il lungometraggio del 2000 orchestrava tre storie nello specchio di un incidente, l’installazione sottrae il conforto dell’inevitabile e ci consegna al regime del forse: gli incontri non sono predestinati, sono collisioni di indizi. È un’etica dello scarto che diventa estetica dell’attenzione.

In questo riattraversamento della memoria filmica, la riflessione critica si stratifica come la città stessa. “Quanti film esistono dentro un film?” — si chiede Alejandro G. Iñárritu.

Come ha osservato David William Foster nel saggio The Canine and the Carnal in Amores Perros (2002), il film si configura come una parabola sull’ambiguità della condizione umana, sospesa tra istinto e coscienza, ferocia e desiderio. A partire dal doppio significato del titolo — perros come “cani” e come “crudeli” — Foster individua nel rapporto tra canino e carnale la chiave di un discorso più ampio sulla vulnerabilità del corpo e sulla sua esposizione alla violenza. I cani, presenti in ciascuna delle tre storie, non sono semplici figure allegoriche ma specchi etici che riflettono le pulsioni dei personaggi: la lealtà, la rabbia, la fame d’amore, la sopravvivenza. Il film, secondo Foster, non umanizza gli animali ma animalizza gli uomini, mostrando come la violenza urbana e la miseria sociale dissolvano ogni confine tra umano e bestiale. Città del Messico è concepita come un corpo ferito, attraversato da cicatrici visibili e invisibili, dove la macchina da presa aderisce alla materia della città come a una pelle. In questa prospettiva, Amores Perros diventa una riflessione laica sulla colpa e sulla possibilità di redenzione attraverso il contatto fisico con la sofferenza altrui: la carne come ultimo luogo possibile dell’etica. Il gesto finale di El Chivo — liberare i cani e riconciliarsi col proprio passato — rappresenta per Foster il momento in cui l’uomo accetta la propria animalità come condizione di compassione e di verità.1

Su questa linea di lettura, Città del Messico nel film non è semplice scenario ma una mappa vivente di tensioni, un organismo che pulsa e collassa insieme ai suoi abitanti. La frammentazione temporale e il montaggio a incastri producono un’esperienza dello spazio più prossima al flusso della memoria che alla narrazione lineare: la città non è raccontata, ma agita. Ogni raccordo somiglia a un corto circuito, ogni movimento di macchina a un respiro trattenuto. Il film, come la città stessa, vive di urti e rifrazioni, alterna la claustrofobia delle intercapedini domestiche all’apertura abbagliante delle arterie metropolitane, componendo una geografia mentale dove intimità e caos coincidono. In questo senso Amores Perros pensa come Città del Messico: discontinua, affollata, in stato d’allarme.2

In continuità con questa visione, ma spostando l’attenzione sul piano geopolitico,

la studiosa britannica Deborah Shaw individua nel film una soglia che segna il passaggio del cinema latinoamericano verso la globalizzazione estetica. Amores Perros, scrive, inaugura un nuovo modello di “transnational art cinema” in cui il realismo sociale si intreccia con la grammatica postmoderna e la frammentazione narrativa diventando riflesso di una società disconnessa, priva di centro. L’incidente che lega i protagonisti è la metafora di un mondo che collassa su sé stesso, dove ogni gesto d’amore è contaminato dalla fame e dalla violenza. Ma nella spietatezza delle relazioni resta, per Shaw, una possibilità di umanesimo ferito: la scoperta, dentro la perdita, di un residuo di solidarietà istintiva. Il film, in questa prospettiva, unisce etica e forma, traducendo la crisi del Messico contemporaneo in una lingua cinematografica capace di parlare al mondo.3

A completare questo orizzonte critico, la studiosa messicana Maricruz Castro Ricalde interpreta Amores Perros come un momento fondativo del Nuevo Cine Mexicano e come allegoria di una nazione spezzata. Nelle sue analisi, la città di Iñárritu diventa la scena in cui il progetto identitario del Messico si frantuma in una molteplicità di corpi, accenti e sopravvivenze. È ciò che Castro Ricalde definisce una “estetica della disintegrazione”: un montaggio di differenze che sostituisce la coesione con la contiguità, e la narrazione con la ferita. L’opera non cerca una redenzione nazionale, ma rivela un archivio emotivo fatto di frammenti, di gesti minimi, di resistenze individuali. In questo senso, il film non è soltanto un ritratto della violenza urbana, ma un atto di memoria affettiva, in cui la vulnerabilità del corpo diventa figura di una collettività dispersa e ancora viva.4

Queste interpretazioni, nel loro insieme, agiscono come preambolo teorico al gesto di Iñárritu, che decide di riaprire la ferita e di esporne la materia prima.

“Durante la fase di editing di Amores Perros oltre trecento chilometri di pellicola sono stati tagliati e lasciati sul pavimento della sala di montaggio. Queste immagini cariche di intensità […] sono rimaste sepolte negli archivi dell’UNAM per venticinque anni. In occasione dell’anniversario del film ho sentito il dovere di riscoprire e riesplorare questi frammenti abbandonati, con la loro grana e i fantasmi di celluloide che contengono. Spogliata di ogni narrazione, questa installazione non è un omaggio, ma una resurrezione: un invito a percepire ciò che non è mai stato. È come incontrare un vecchio amico che non abbiamo mai visto prima”, spiega il regista.

I cani – dichiarati nel titolo e disseminati nelle immagini – non sono qui simboli facili di ferocia. Sono mediatori, animali psicopompi che nella tradizione mesoamericana accompagnano oltre il fiume e, nel dispositivo del film, traghettano lo spettatore tra classi, quartieri, stati della coscienza. In mostra, la loro presenza è un battito a distanza: appaiono, scompaiono, tornano come un motivo musicale che fa soglia tra scene, ricordandoci che la città è un ecosistema in cui l’umano è solo una delle specie del racconto.

Iñárritu non feticizza la nostalgia della pellicola. Al contrario: ne stressa le imperfezioni – graffi, impunture, code ottiche, aperture di diaframma – come indizi del tempo che passa sul dispositivo e sul mondo. Non “vintage”, ma politica della materia: come se il film avesse assorbito le torsioni sociali di Città del Messico e ora ce le restituisse nel granello fisico dell’emulsione. A ogni spuntatura, un sobbalzo: non c’è superficie liscia, non c’è algoritmo che normalizzi; c’è resistenza. In un’epoca che chiede al visivo di essere fruibile e piatto, Sueño Perro difende la ruvidità.

La struttura a stanze funziona come un montaggio spaziale: attraversare i bui consecutivi è come passare da una bobina all’altra, con una memoria corta che si riaccende per intonazioni, non per coordinate. L’udito diventa guida: frammenti ambientali, suoni musicali sghembi, echi di strada compongono una drammaturgia senza dialogo. Di quando in quando, è il suono – non l’immagine – a suggerire un raccordo invisibile tra sequenze lontane. È come guardare il film dal suo verso, dove il senso non precede la forma ma si coagula cammin facendo. Al centro dell’installazione c’è una profonda venerazione per la materialità del 35mm che, con la sua grana, lo sfarfallio e il calore, evoca un senso di nostalgia viscerale: il ritorno del cinema come corpo vivo.

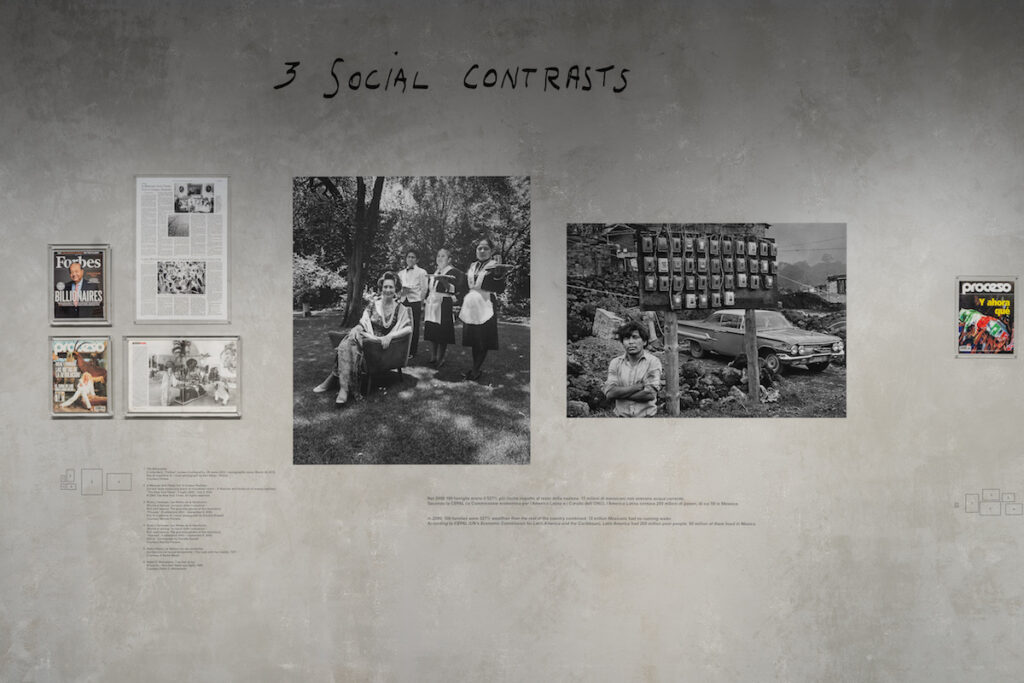

Al piano superiore, l’intervento di Juan Villoro, scrittore e giornalista messicano, dilata il perimetro dall’opera alla storia. Mexico 2000: The Moment that Exploded non è un apparato didascalico: è un montaggio parallelo di cronaca e immaginario, con fotografie, testi e frammenti sonori a segnare l’ora legale del Paese. “Amores Perros si può collocare in un preciso momento storico,” spiega Villoro. “Nel canonico anno 2000 il Messico stava attraversando un raro e atteso momento di speranza: dopo 71 anni al potere, il PRI aveva perso le elezioni presidenziali e il paese si preparava a scoprire una vera democrazia. Allo stesso tempo la realtà messicana si presentava come un panorama fatto di disuguaglianze, corruzione e violenza.” Il suo intervento traccia una mappa delle condizioni politiche, familiari, religiose ed economiche che hanno dato vita alle tre storie interconnesse e narrate nel film. “Girato in un ‘momento di transizione’, Amores Perros non rifletteva la fine di un’era, ma l’inizio di un tracollo. Venticinque anni dopo la sua rilevanza sociale è disturbante: ciò che accadeva allora, accade ancora oggi. La sua esplosione è ancora in corso.”

Questa geologia di frammenti rimette al centro ciò che Amores Perros aveva reso in forma narrativa: la compresenza di mondi che non smettono di sfiorarsi – slum e attici, autisti e modelle, randagi e pedigree – dentro una metropoli che funziona come livellatrice e amplificatore. Ma nel passaggio dal cinema alla mostra cambia l’uso del tempo: non più un “prima–dopo” orchestrato, bensì una durata perforata, fatta di ritorni e scarti. L’effetto non è confusione bensì attenzione dispersa, quella che la città esige per non soccombere. Si guarda come si vive: per appigli.

In questa logica, Sueño Perro è anche una riflessione sulla sovranità del montaggio nel XXI secolo. Non solo come tecnica audiovisiva, ma come procedura cognitiva che organizza l’eccesso. L’installazione mostra una possibile risposta: non ridurre, ma rendere poroso; non chiudere, ma predisporre passaggi. Ecco perché l’opera non teme la ripetizione: la usa come prova di stress, come banco in cui il senso, per differenza minima, cambia intensità.

Che cos’è dunque il “sogno” del titolo? Non l’allucinazione romantica, ma un regime di verità intermittente in cui le immagini mantengono la loro libertà di non farsi catturare interamente. Un sogno materialista, se si vuole: fatto di ingranaggi, di mani che caricano bobine, di un gesto tecnico divenuto raro quanto gli operatori che lo padroneggiano. La promessa “immersiva” – parola inflazionata, spesso svilita – qui ritrova senso: non è spettacolo avvolgente, è impegno dei sensi, è disponibilità a perdersi nei corridoi dove l’immagine e la città si scambiano il ruolo.

“Con questo progetto,” osserva Miuccia Prada, Presidente e Direttrice di Fondazione Prada, “vogliamo aprire nuove prospettive sul lavoro di Iñárritu e su un film che, sin dagli esordi, ha unito la forza del realismo alla densità del simbolismo. A venticinque anni dalla sua uscita, Amores Perros continua a parlare al presente e a restituire, con potenza visiva ed emotiva, tutta la complessità del mondo in cui viviamo.”

Se Amores Perros apriva, all’inizio del millennio, una stagione del cinema messicano capace di ibridare cronaca e invenzione, Sueño Perro ne distilla il concentrato etico: guardare il mondo là dove è più inospitale senza smettere di amarlo. Non c’è cinismo, non c’è redenzione facile: c’è un amore cattivo che è, al tempo stesso, lucidità e responsabilità dello sguardo. Alla fine della visita non possediamo il film: è il film – o meglio, i suoi scarti – ad averci posseduti quel tanto che basta per farci uscire con la città ancora addosso, come un odore. “Immergersi nella celluloide grezza e smembrarla è stata una sorta di impresa archeologica. Infinita ed esaltante.

Qui, i frammenti sono messi a nudo: nessuna storia a mascherarli, spogli e privi di forma, presentati in open gate. Brandelli riemersi del paesaggio sonoro di Città del Messico. L’innocenza di forme incompiute in uno specchio.

Un mosaico di cosa è stato, di cosa avrebbe potuto essere e di cosa non è mai stato.”

scrive Iñárritu.

L’installazione occupa il piano terra del Podium della Fondazione Prada di Milano e resterà aperta fino al 26 febbraio 2026, prima di spostarsi in altre istituzioni internazionali tra cui LagoAlgo (Città del Messico) e The Los Angeles CountyMuseum of Art (LACMA) nel corso del 2026. Sueño Perro segna la terza collaborazione tra Iñárritu e Fondazione Prada, dopo la rassegna cinematografica Flesh, Mind and Spirit (Seul, 2009; Milano, 2016) e l’installazione in realtà virtuale CARNE y ARENA (Milano, 2017), selezionata al Festival di Cannes e premiata con un Oscar speciale dal Board of Governors of the Academy. È giusto che accada: Sueño Perro non è un reliquiario, è una tecnologia di passaggio. In ogni sede cambierà la traiettoria degli sguardi, la qualità dell’aria, il passo dei visitatori: e cambierà, inevitabilmente, anche il suo senso locale. Come tutte le opere vive, non finisce: continua. Così l’opera si riscrive nello spazio che la accoglie, come se ogni luogo la obbligasse a respirare di nuovo. Forse è questo il destino delle immagini: non restare, ma ritornare altrove, mutate, respirate da altri corpi, nell’oscillazione continua tra perdita e rivelazione, tra luce e sopravvivenza.

Come tutte le opere vive, Sueño Perro non si chiude: prosegue nel tempo di chi la guarda, nella memoria della materia, nel respiro di ciò che non si lascia archiviare.

- David William Foster, The Canine and the Carnal in Amores Perros, in Latin American Literary Review, vol. 30, n. 60, 2002, pp. 5–20. ↩︎

- Paul Julian Smith, Contemporary Mexican Cinema 1989–2016: History, Space and Identity, Palgrave/BFI, 2017.

↩︎ - Deborah Shaw, Contemporary Cinema of Latin America: Ten Key Films, Continuum, 2003, pp. 1–24.

↩︎ - Maricruz Castro Ricalde, El cine mexicano del nuevo milenio, Universidad de Guadalajara, 2004; Reescrituras de la nación: el cine mexicano del nuevo milenio, Universidad Autónoma de Querétaro, 2009. ↩︎

Sueño Perro. Cartography of a Wounded City

La ciudad de México no es un caos: es el orden del desorden, la legalidad de la confusión, la forma del desconcierto

— Carlos Monsiváis, Los rituales del caos (1995)

There is a moment, stepping into the darkness of the Podium, when cinema ceases to be a window and becomes a machine again. The breath of the analogue projectors, their steady hum, the cone of light slicing through dust: all of it reminds us that a moving image is, first of all, a matter that resists. In Sueño Perro: Instalación Celuloide, a multisensory exhibition conceived by Alejandro G. Iñárritu for Fondazione Prada to mark the twenty-fifth anniversary of Amores Perros (2000), the Mexican director reopens the body of his own film and exposes its musculature — the ligaments of editing, the tendons of duration, the scars of the work print. The protection of narrative is gone; in its place, a landscape of remnants that must be crossed with the body, not merely with the gaze.

The starting point is both known and unexpected: over three hundred kilometres of discarded film stock — sixteen million frames — left for twenty-five years in the archives of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM). Through a work of visual and sonic archaeology, Iñárritu now reassembles them into an environmental device that translates the film into a city. The sequences no longer “tell” — they breathe. They return to being events of light and sound offered through proximity, rhyme, and short-circuit. Whereas the 2000 feature orchestrated three stories mirrored in a single accident, the installation withdraws the comfort of the inevitable and delivers us to the regime of perhaps: encounters are not predestined but collisions of clues. It is an ethics of discard turned into an aesthetics of attention.

In this re-crossing of filmic memory, critical reflection accumulates like the city itself. “How many films exist within a film?” — asks Alejandro G. Iñárritu.

As David William Foster noted in The Canine and the Carnal in Amores Perros (2002), the film unfolds as a parable of the human condition’s ambiguity — suspended between instinct and consciousness, ferocity and desire. Drawing on the double sense of the title — perros as “dogs” and as “cruel” — Foster finds, in the tension between the canine and the carnal, the key to a wider discourse on the body’s vulnerability and its exposure to violence. The dogs that inhabit each of the three stories are not mere allegorical figures but ethical mirrors reflecting the characters’ drives: loyalty, rage, hunger for love, survival. The film, according to Foster, does not humanise animals but animalises men, revealing how urban violence and social misery dissolve every border between the human and the bestial. Mexico City becomes a wounded body, traversed by visible and invisible scars, where the camera adheres to the city’s matter as if to a skin. In this perspective, Amores Perros becomes a secular meditation on guilt and on the possibility of redemption through the physical contact with another’s suffering — flesh as the last possible site of ethics. El Chivo’s final gesture — releasing the dogs and reconciling with his past — marks, for Foster, the moment when man accepts his own animality as the condition of compassion and truth.

On this line of reading, Mexico City in the film is not a mere backdrop but a living map of tensions — an organism that pulses and collapses with its inhabitants. Temporal fragmentation and interlocking montage generate an experience of space closer to the flow of memory than to linear narration: the city is not described but enacted. Each cut resembles a short circuit, each camera movement a held breath. The film, like the city itself, lives through shocks and refractions, shifting between the claustrophobia of domestic interstices and the blinding openness of metropolitan arteries, composing a mental geography where intimacy and chaos coincide. In this sense, Amores Perros thinks like Mexico City itself: discontinuous, crowded, permanently on alert.

In continuity with this vision — though moving the focus onto a geopolitical plane — the British scholar Deborah Shaw identifies in the film a threshold marking Latin American cinema’s passage into aesthetic globalisation. Amores Perros, she writes, inaugurates a new model of “transnational art cinema,” in which social realism intertwines with postmodern grammar, and narrative fragmentation becomes the reflection of a disconnected, centreless society. The car crash that binds the protagonists is the metaphor of a world collapsing upon itself, where every gesture of love is contaminated by hunger and violence. Yet within the relentlessness of these relationships, Shaw locates a possibility of wounded humanism: the discovery, within loss, of a residue of instinctive solidarity. In this perspective, the film unites ethics and form, translating the crisis of contemporary Mexico into a cinematic language capable of speaking to the world.

Completing this critical horizon, the Mexican scholar Maricruz Castro Ricalde reads Amores Perros as both a founding moment of the Nuevo Cine Mexicano and as an allegory of a fractured nation. In her analyses, Iñárritu’s city becomes the stage upon which Mexico’s identity project splinters into a multiplicity of bodies, accents, and survivals. It is what Castro Ricalde calls an “aesthetics of disintegration”: an editing of differences that replaces cohesion with contiguity, and narration with the wound. The work does not seek national redemption but reveals an emotional archive made of fragments, minor gestures, and individual forms of resistance. In this sense, Amores Perros is not merely a portrait of urban violence but an act of affective remembrance, where the body’s vulnerability becomes the figure of a dispersed yet still living collectivity.

Taken together, these interpretations serve as a theoretical prelude to Iñárritu’s gesture — his decision to reopen the wound and expose its raw matter.

“Over a million feet of film were left on the cutting room floor during the editing of Amores Perros. These intensely charged images, sixteen million still frames, were buried in the UNAM film archives for 25 years. On the occasion of the film’s anniversary, I felt compelled to revisit and re-explore these abandoned fragments, with the grain and the ghosts of celluloid which they hold. Stripped of all narrative, this installation is not a tribute, but a resurrection — an invitation to feel what never was. Like meeting an old friend, we have never seen before.”, explains the director.

The dogs — declared in the title and scattered throughout the images — are not easy symbols of ferocity. They are mediators, psychopomps who, in Mesoamerican tradition, guide souls across the river and, within the film’s device, ferry the spectator between classes, districts, and states of consciousness. In the exhibition, their presence is like a pulse from afar: they appear, vanish, and return like a recurring musical motif that opens a threshold between scenes, reminding us that the city is an ecosystem in which the human is only one of the species in the tale.

Iñárritu does not fetishise the nostalgia of celluloid. On the contrary, he stresses its imperfections — scratches, splices, optical tails, bursts of aperture — as clues to the time inscribed upon both device and world. Not “vintage,” but a politics of matter: as if the film had absorbed the social torsions of Mexico City and now returned them to us in the physical grain of its emulsion. Each splice is a jolt; there is no smooth surface, no algorithm to normalise it — only resistance. In an age that demands images to be consumable and flat, Sueño Perro defends roughness.

The room-based structure functions as a spatial montage: to cross its consecutive darknesses is like moving from one reel to the next, carrying a short memory that reignites through tonalities rather than coordinates. Hearing becomes a guide: environmental fragments, skewed musical motifs, street echoes compose a dramaturgy without dialogue. At times, it is sound — not image — that suggests an invisible bridge between distant sequences. It is like watching the film from its reverse side, where meaning does not precede form but coagulates as one walk. At the centre of the installation lies a profound veneration for the materiality of 35mm film, whose grain, flicker, and warmth evoke a visceral nostalgia — the return of cinema as a living body.

On the upper floor, the intervention by Mexican writer and journalist Juan Villoro expands the perimeter from artwork to history. Mexico 2000: The Moment that Exploded is not a didactic apparatus but a parallel montage of chronicle and imagination, with photographs, texts, and sonic fragments marking the country’s official hour. “Amores Perros can be located at a precise historical juncture, – Villoro explains- Perros. In the canonical year of 2000, Mexico was experiencing a rare moment of long-awaited hope: after 71 years in power, the Institutional Revolutionary Party had finally lost a presidential election, and the country was preparing to discover genuine democracy. At the same time, reality presented a panorama of inequality, corruption, and violence”. His contribution maps the political, familial, religious, and economic conditions that gave rise to the three interwoven stories told in the film. “Filmed at a ‘moment of change’, Amores Perros did not reflect the end of an era but rather the beginning of a downfall. Twenty-five years later, its social relevance is alarming: what was happening then is still happening now. Its explosion is still ongoing.”

This geology of fragments recentres what Amores Perros had once rendered in narrative form: the coexistence of worlds that never cease to brush against one another — slums and penthouses, drivers and models, strays and pedigrees — within a metropolis that functions both as leveler and amplifier. Yet in the passage from cinema to exhibition, the use of time changes: no longer an orchestrated “before–after,” but a perforated duration made of returns and skips. The effect is not confusion but dispersed attention — the kind the city itself demands in order not to collapse. One looks as one lives: by grasping for holds.

Within this logic, Sueño Perro also becomes a meditation on the sovereignty of montage in the twenty-first century — not only as an audiovisual technique but as a cognitive procedure that organises excess. The installation offers a possible answer: not to reduce, but to make porous; not to close, but to prepare passages. This is why the work does not fear repetition: it uses it as a stress test, as a plane on which meaning, through the slightest variation, shifts in intensity.

What, then, is the “dream” of the title? Not the romantic hallucination, but a regime of intermittent truth in which images retain their freedom never to be entirely captured. A materialist dream, if you will — made of gears, of hands loading reels, of a technical gesture now as rare as those who master it. The much-abused promise of the “immersive” finds here its true sense: not enveloping spectacle, but sensory engagement, a willingness to lose oneself in the corridors where image and city exchange roles.

With this project, as stated by Miuccia Prada, President and Director of Fondazione Prada, “ we aim to open new perspectives on Iñárritu’s work and on a film that, from its very start, combined the force of realism with the density of symbolism. Twenty-five years after it was released, Amores Perros continues to speak to the present and to capture, with visual and emotional power, the full complexity of the world we live in.”

If Amores Perros inaugurated, at the dawn of the millennium, a season of Mexican cinema capable of fusing chronicle and invention, Sueño Perro distils its ethical core: to look at the world where it is most inhospitable without ceasing to love it. There is no cynicism, no easy redemption — only a fierce love that is, at once, lucidity and responsibility of vision. At the end of the visit, we do not possess the film: it is the film — or rather, its remnants — that have possessed us just enough to make us leave with the city still clinging to us like a scent.

“Digging and dismembering through the raw celluloid felt like an archaeological adventure. Endless and exhilarating. Here, the fragments stand exposed—no story to disguise them, unadorned and unshaped, presented in open gate. Rescued soundscape particles of Mexico City. The innocence of unfinished forms in a mirror. A mosaic of what was, what might have been and what never came to be”, writes Iñárritu. The installation occupies the ground floor of the Podium at Fondazione Prada in Milan and will remain open until 26 February 2026, before travelling to other international institutions, including LagoAlgo (Mexico City) and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) later that year. Sueño Perro marks the third collaboration between Iñárritu and Fondazione Prada, following the film programme Flesh, Mind and Spirit (Seoul, 2009; Milan, 2016) and the virtual reality installation CARNE y ARENA (Milan, 2017), which was selected for the Cannes Film Festival and honoured with a special Oscar by the Board of Governors of the Academy.

It is right that it should be so: Sueño Perro is not a reliquary, but a technology of passage. In every venue, it will alter the trajectory of gazes, the quality of air, the pace of visitors — and, inevitably, its local meaning. Like all living works, it does not end: it continues. Thus, the work rewrites itself within the space that receives it, as though each site compelled it to breathe anew. Perhaps this is the destiny of images: not to remain, but to return elsewhere — transformed, inhaled by other bodies, within the constant oscillation between loss and revelation, between light and survival.

Like all living works, Sueño Perro does not close: it continues in the time of those who see it, in the memory of matter, in the breath of what refuses to be archived.

¹ David William Foster, The Canine and the Carnal in Amores Perros, in Latin American Literary Review, vol. 30, no. 60, 2002, pp. 5–20.

² Paul Julian Smith, Contemporary Mexican Cinema 1989–2016: History, Space and Identity, Palgrave/BFI, 2017.

³ Deborah Shaw, Contemporary Cinema of Latin America: Ten Key Films, Continuum, 2003, pp. 1–24.

⁴ Maricruz Castro Ricalde, El cine mexicano del nuevo milenio, Universidad de Guadalajara, 2004; Reescrituras de la nación: el cine mexicano del nuevo milenio, Universidad Autónoma de Querétaro, 2009.