English version below –

«Tutte le cose si scambiano con il fuoco e il fuoco con tutte le cose, come le merci con l’oro e l’oro con le merci.»

— Eraclito, Frammento 90 (G. Colli in La sapienza greca, 1978)

Soy Fuego: così si intitola l’ultima mostra di Hannah Collins a Madrid, presso la galleria Prats Nogueras Blanchard (8 maggio-26 luglio 2025). Non un semplice nome, ma un sortilegio, un mantra pronunciato in prima persona che rivela subito la vocazione profonda di questo progetto: dissolvere le distanze tra il corpo umano e la materia che arde, tra la memoria che trattiene e la fiamma che consuma. Collins, nata a Londra nel 1956, finalista del Turner Prize nel 1993, autrice di straordinarie installazioni fotografiche e progetti filmici dedicati alla memoria collettiva, alla trasformazione culturale e alla fragile architettura del tempo, conferma qui la sua capacità di tenere insieme poesia, ricerca etnografica e visione critica. Dalle sue prime opere monumentali che esploravano le architetture urbane e gli spazi disabitati, fino ai lunghi soggiorni tra i Rom in Spagna e Russia, la sua traiettoria è segnata da un gesto sempre uguale: abitare a lungo, lasciarsi mutare dall’incontro con comunità e paesaggi, ascoltare le storie che altri mondi hanno da offrire.

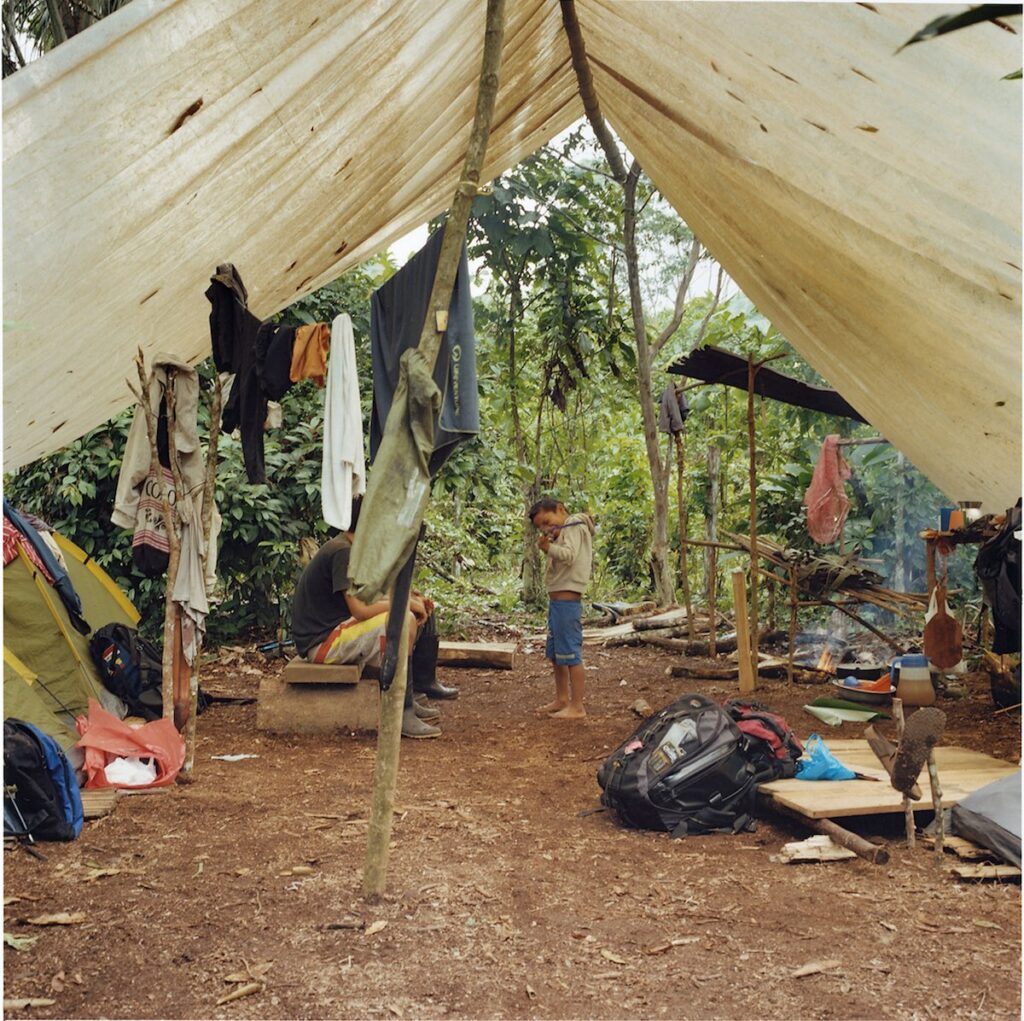

Soy Fuego è maturata lungo i cammini di Collins, tra viaggi estesi e incerti in America Latina. L’artista ha attraversato l’Amazzonia colombiana, è salita sui vulcani di Michoacán, ha guardato il cielo magro dell’Atacama e si è addentrata nelle foreste di Veracruz, condividendo saperi e riti che insegnano a leggere meglio i cicli, le ricadute, le stagioni segrete delle cose. È da questo che viene il suo fuoco: da una prossimità paziente, da un apprendere lento che scalfisce la pelle e rimane.

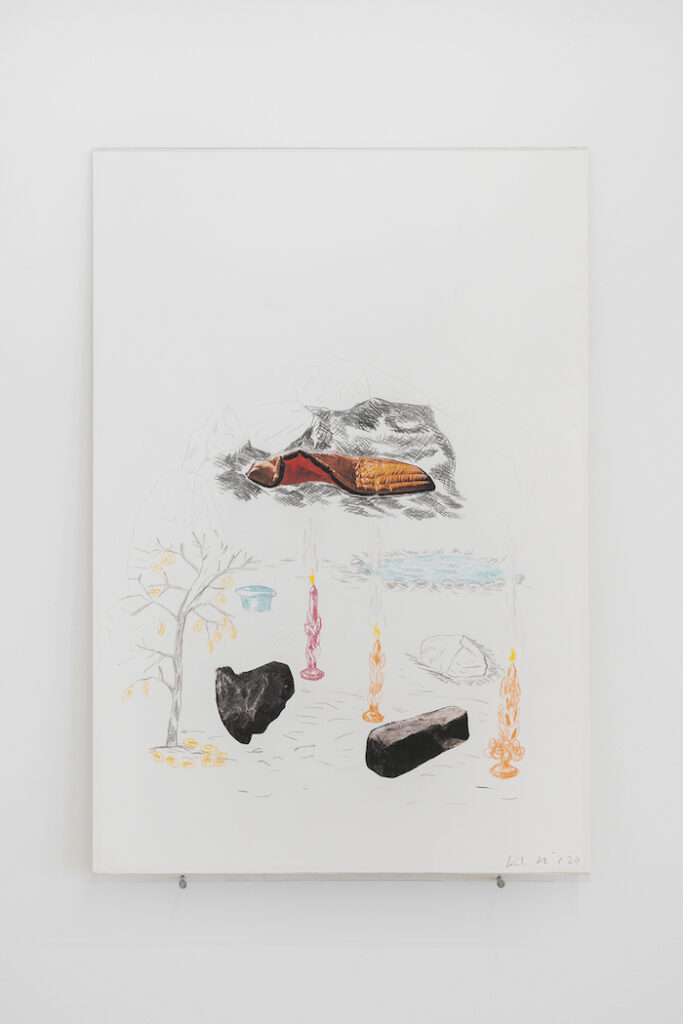

In questa mostra Collins porta tracce del tempo trascorso come ospite di comunità indigene per le quali il fuoco non è semplice strumento o decorazione rituale, ma una creatura viva con cui entrare in relazione. Nelle fotografie di grande formato, nel candore delle candele votive modellate a mano, nei frammenti di disegni che costellano lo spazio, si avverte un legame che si estende oltre la dimensione visiva, coinvolgendo anche questioni più ampie di giustizia ecologica e di riconoscimento dei saperi locali. Non a caso Collins racconta: «Il mio compito era trovare una memoria diversa, con associazioni positive, modi di relazionarsi alla natura in equilibrio, senza essere estrattiva. In Amazzonia ho dovuto rinunciare alla mia idea di controllo: è stato un processo graduale e minuzioso, come imparare a leggere una mappa che prima non capivo. Ho visto il fuoco sul copale guidarci nella notte, ma solo dopo, soggiornando con un anziano sciamano, la mia percezione delle piante e della terra si è realmente trasformata.»

È in questo cedere, in questo lasciare che il fuoco passi attraverso di lei, che l’opera si incendia di senso e si fa metamorfosi, più che documento. Questo approccio ci ricorda la concezione di Eraclito del fuoco come «arconte di tutte le cose», principio che regola il mutamento universale, o anche Bachelard che, nella Psychanalyse du feu, scrive del fuoco come di ciò che «ci penetra, ci trasforma, si confonde con la sostanza dei nostri sogni». Più recentemente Federico Campagna, riflettendo su ontologia, mito e pluriverso (in Technic and Magic: TheReconstruction of Reality, Bloomsbury Academic 2018), ha mostrato come queste narrazioni arcaiche e questi elementi naturali possano diventare contro-narrazioni necessarie di fronte ai dispositivi estrattivi del capitalismo globale. Il fuoco, in questo senso, è anche un linguaggio politico, una forma di resistenza sottile.

A differenza di molti artisti che ancora oggi guardano ai popoli dell’Amazzonia con l’occhio dell’antropologo o del turista estetico, Collins sceglie di restare a lungo, di condividere gesti minimi, di lasciarsi impregnare dal ritmo lento delle relazioni. Afferma con chiarezza: «Non può essere che si possa fare solo un autoritratto. Deve essere possibile entrare abbastanza in relazione con l’altro perché accada qualcosa. La società cambia costantemente nel modo in cui guarda e negozia il proprio ambiente. Io sono molto esitante. A volte filmo dal basso, come quando ho lavorato con la comunità gitana a La Mina, per costruire la complessità che vivo in forme positive». In questa reciprocità esitante si rivela il nucleo etico del suo lavoro: l’arte come atto fragile, teso tra rischio e fiducia, come materia che si lascia toccare e bruciare.

Il paesaggio della mostra in corso a Madrid spazia dalle miniere abbandonate di Almería, cavità che hanno inghiottito mani e sudore e ora sono lì vuote, come bocche asciutte, a un geode di quarzo, che custodisce un segreto di luce incastonato nella roccia, e più lontano l’Atacama, che nel suo cielo sottile conserva tracce di corpi celesti che hanno attraversato il buio. Poi ci sono frutti, foglie, piccoli gesti quotidiani colati in cera e bronzo, come se si volesse fermare il tempo in una carezza che non passa. Così, nello spazio, si danno appuntamento l’organico e l’artificiale, l’ancestrale e il contemporaneo. È a questo incrocio che Collins posa lo sguardo sul fuoco, non come minaccia ma come scintilla necessaria, un filo che tiene insieme la terra, il corpo, e quel che resta del cielo.

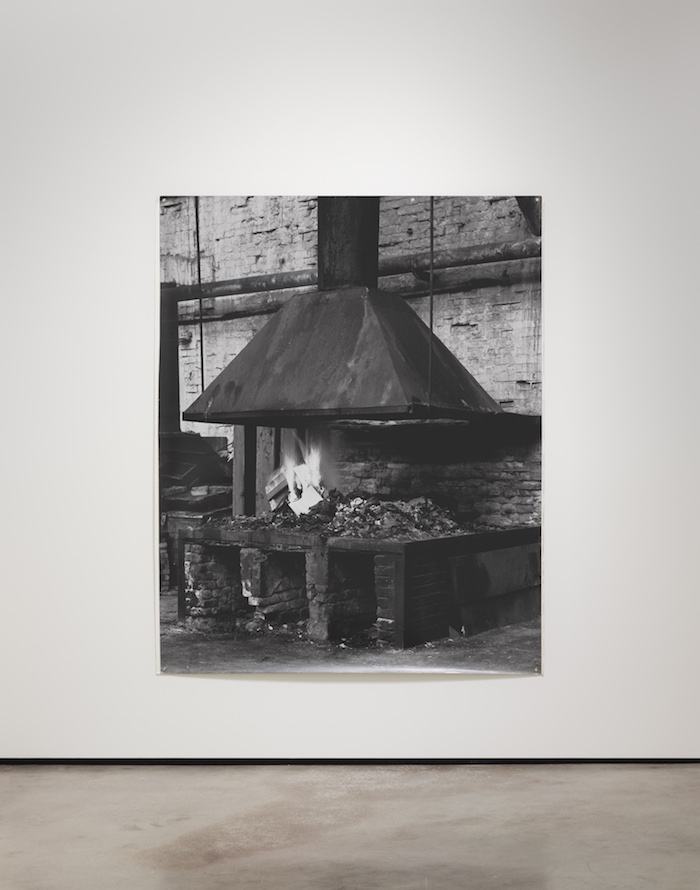

Questo richiamo al fuoco non è un’eccezione isolata nella ricerca di Collins. Opere come Flaming Forest (2021), grande fotografia pigmentata nata per la stessa stagione espositiva di Soy Fuego, e i più raccolti scatti di In the Course of Time (12) Small Fire (1996), mostrano come la combustione, reale o evocata, attraversi da tempo il suo immaginario. Nel primo caso, la foresta pare trattenere un bagliore segreto, un incandescente stato di sospensione; nel secondo, il piccolo fuoco diventa un segno minimo ma assoluto, una presenza silenziosa che arde e resta. Sono lampi che tornano, in modi diversi, a intrecciare la materia del mondo con quella del ricordo, come se la fiamma fosse sempre, in fondo, un frammento di memoria che cerca un corpo per continuare a bruciare.

È lo stesso fuoco, lo stesso richiamo tellurico, a condurre Collins a lavorare sul soggetto dei vulcani per la XII Biennale di Lanzarote (27 gennaio–5 aprile 2025). A cura di Alicia Chillida, il suo progetto si inscrive in un più ampio programma che, dedicato al tema “Lanzarote Planetario”, esplora ecologia, sostenibilità, le relazioni tra identità insulare e immaginari trans-species. Lanzarote come un planetario naturale, un’isola vulcanica che diventa osservatorio del cielo e specchio della Terra, un luogo dove il paesaggio roccioso racconta la memoria geologica e si connette all’astronomia, al cosmo, alla visione notturna. Unendo terra e cielo, vulcani e stelle, il progetto riflette sull’origine e il destino dei luoghi e sul modo in cui li abitiamo.

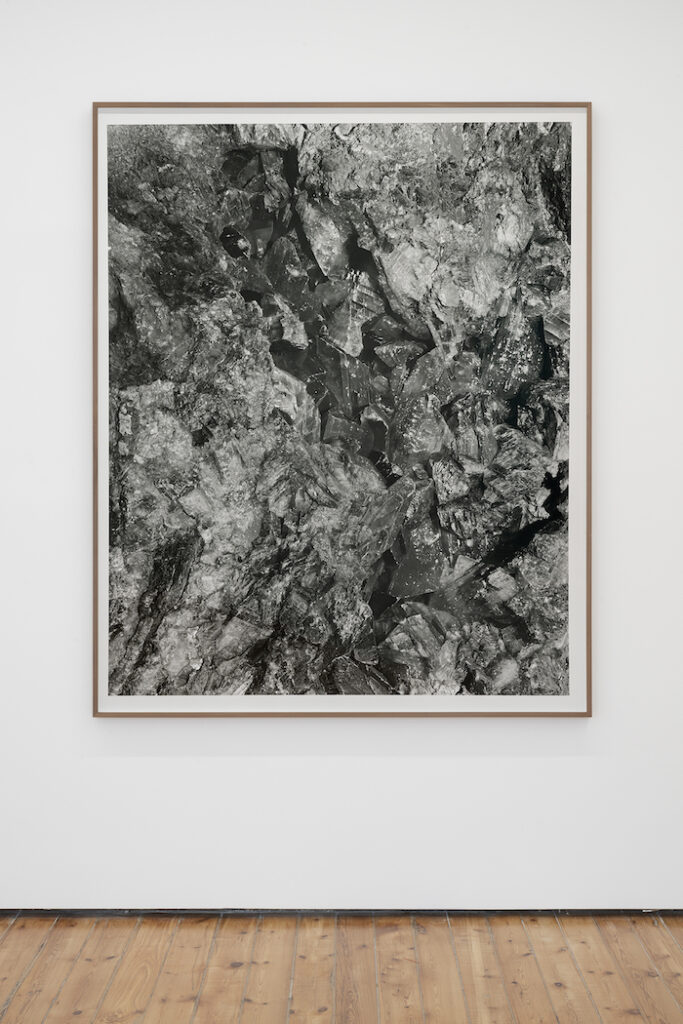

Between Volcanos / Entre Volcanes (2021–2025), una sorta di planetario sentimentale, nasce da una lunga ricerca di Collins sul vulcano Paricutín in Messico, proseguita con un lavoro sul campo condotto a Lanzarote nel 2024, tra i paesaggi di Timanfaya e La Corona, in collaborazione con studiosi, agronomi e artisti locali. Il risultato è un’installazione che combina fotografie in grande formato, testi autobiografici scritti a carboncino direttamente sui muri e un intreccio di testimonianze orali e osservazioni scientifiche, restituendo il vulcano come entità viva e memoriale, luogo di metamorfosi geologiche e umane.

Il Paricutín è nato da una crepa nella terra, all’improvviso. Non un monte antico, ma un figlio del 1943, spuntato da un campo di granturco sotto gli occhi di Dioniso Pulido, il contadino che ne udì prima il brontolio e poi vide il fumo e il terriccio rigirarsi, come fosse stato colto da un tremito interno. In pochi giorni divenne un gigante, divorò villaggi, lasciò solo un campanile conficcato nella lava, che ancora oggi sbuca come un dito che indica il cielo. I Purépecha lo chiamano Parhíkutini, che significa -il posto dell’altro lato-: un altrove dove la terra si apre e ricorda di essere viva, dove il fuoco custodisce storie che bruciano a bassa voce. Forse è questo che Collins ha cercato in quei crateri: un paesaggio che si scrolla di dosso la pelle vecchia e mostra cosa c’è sotto, un suolo che si fa archivio di cenere e possibilità. In Viaggio al centro della terra, pubblicato a Parigi nel 1864, Jules Verne inventa un cunicolo invisibile sotto i continenti, un corridoio di fuoco e caverne che unisce il cratere di Sneffels in Islanda alle bocche dello Stromboli, due vulcani lontani che si parlano attraverso il ventre caldo del pianeta. È un racconto della terra come corpo poroso, penetrabile, che sotto la crosta nasconde radici comuni. Il protagonista, un giovane studente di mineralogia, attraversa la terra di lato, come si fa con un amico, passando sotto le parole. È un viaggio che lega crateri lontani, mettendo in comunicazione focolai separati da oceani. Non è solo avventura, è un modo di dire che sotto la crosta ci sono vene che si toccano senza saperlo, che il fuoco conserva memoria dei passi che l’hanno calpestato.

Perché la terra, quando vuole, ricorda tutto.

In questo movimento che sfiora la geologia per lambire il tempo, si apre un’eco letteraria, un passo sotterraneo che lega le opere di Collins al racconto di Verne, e che Michel Serres ha saputo illuminare nel saggio “Jules Verne: la science et l’imaginaire”, incluso in Hermès II. L’interférence (1972). Lì Serres ricorda come discendere nelle viscere della terra non sia soltanto attraversare uno spazio, ma tornare a un tempo remoto, quello inciso negli strati della roccia, nelle pieghe del suolo che custodiscono la memoria del mondo. È un viaggio che porta con sé la fame di chi cerca, mani sporche di polvere e un occhio pronto a decifrare le scritture minerali. Così Collins si muove tra terre vulcaniche, crepe, crateri, come se varcasse una soglia che non è soltanto geografica, ma temporale. Va sotto la crosta, a scovare non il fuoco vivo del magma, ma qualcosa di più antico ancora: l’archivio silenzioso dove il tempo si piega e si addensa, e ci parla in un sussurro di lava rappresa. Si potrebbe dire, allora, che le sue opere sono un calarsi nel ventre del pianeta per interrogarne le memorie incandescenti, per leggere, pagina dopo pagina, le storie che la terra scrive da millenni, senza fretta, nella sua lingua di pietra.

Il progetto di Collins si muove in questo solco immaginario quando lega il Paricutín messicano ai vulcani di Lanzarote, costruendo un’alleanza segreta tra paesaggi lontani. Non li accosta come farebbe un atlante, ma li fa risuonare l’uno nell’altro, come se la lava avesse memoria, come se un’eruzione in un emisfero potesse far tremare la cenere in un altro. È ancora un modo di dire che la terra custodisce parentele ignote, e che il fuoco, anche se sepolto, ricorda. In questo dialogo tra il Paricutín e i crateri canari, Collins ricuce memorie stratificate, riattivando miti del fuoco e pratiche di racconto che appartengono a comunità distanti ma accomunate dallo stesso battito tellurico. Qui la terra ha il fiato caldo sotto la crosta e i crateri sono bocche spente che hanno conosciuto la fiamma, Collins si muove tra le rocce nere con la stessa cautela con cui si passa accanto a un animale addormentato.

In L’Amante del Vulcano, Susan Sontag lascia affiorare una verità semplice, quasi disarmante. «un vulcano non si lascia possedere. Si lascia attendere». Forse è questo che Hannah Collins cerca: un’attesa lunga, che tenga insieme la rovina e la rinascita, la minaccia e il germe. Nelle sue immagini la materia sembra ancora viva, resta lì a promettere un altro sussulto; il suo è un paesaggio che conosce la combustione, e per questo continua a ricordare. La terra arde ancora sotto la superficie, e i crateri portano scritto nella carne il tempo delle eruzioni: è in questa sostanza geologica che Collins ritrova un linguaggio primordiale in cui la materia fusa diventa specchio delle nostre metamorfosi interiori e dei nostri incendi futuri.

In tale itinerario di ceneri e bagliori Soy Fuego non si offre come un racconto da decifrare, ma come un varco percettivo, un invito a restare nella combustione, ad ascoltarne i crepitii, a lasciare che la pelle ne trattenga l’odore. Qui il fuoco non è soltanto simbolo o minaccia, ma materia interiore, lampo che ci percorre, memoria ardente di ciò che siamo stati e di ciò che, forse, potremmo ancora diventare.

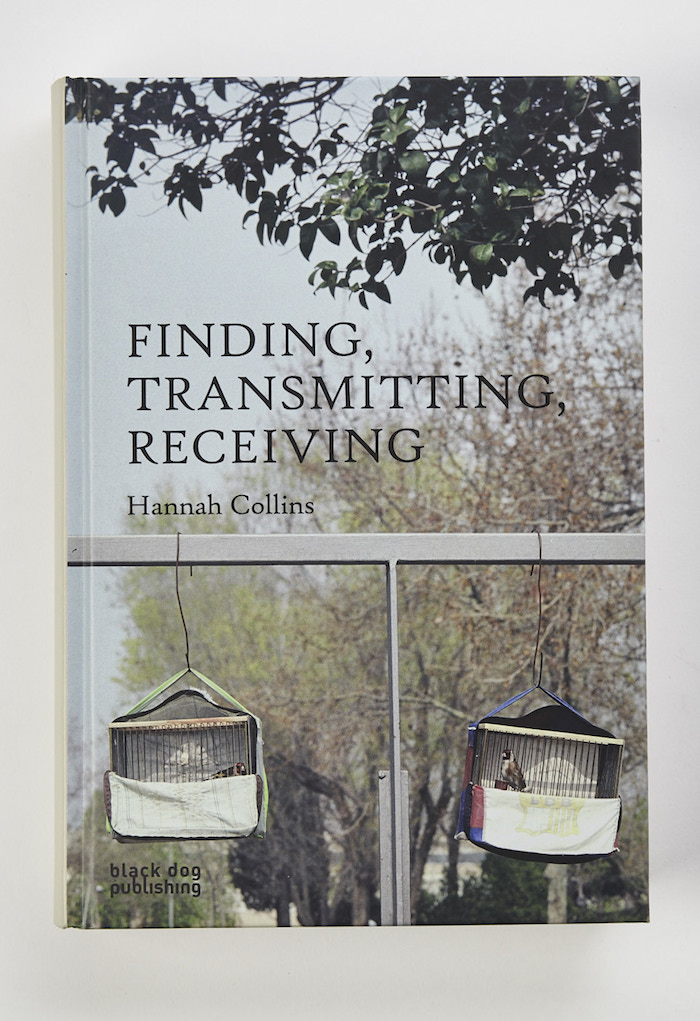

Parlare poi dei libri di Hannah Collins, da Finding, Transmitting, Receiving a The Fragile Feast, significa avvicinarsi a un altro focolare, in cui parole e immagini si tengono strette, custodiscono ciò che resta e lo offrono al tempo. Mi viene spontaneo chiederle: –Quale pensi sia il valore politico e poetico di affidare alla pagina stampata questi materiali? E in che modo il libro agisce diversamente da una mostra nel custodire e restituire una memoria collettiva? «Le mostre sono uniche -risponde- un’interazione con lo spazio in un preciso momento. I libri invece segnano un rapporto particolare tra parola e immagine, con un legame differente al tempo e al pubblico. Politicamente hanno una portata più ampia. Per questo mi dispiace quando un’esposizione resta senza libro, come accadde con We Will Walk, la mostra che ho curato sul Sud dell’America. Dopo ho lavorato con Doris Derby per A Civil Rights Journey, che è arrivato al primo posto in alcune classifiche americane: era il libro che doveva esistere, e sono orgogliosa di averlo realizzato.»

We Will Walk, con la co-curatela di Paul Goodwin e presentato alla Turner Contemporary di Margate (7 feb – 3 mag 2020) si concentrava sull’Alabama e sulle comunità afroamericane che lì hanno sviluppato forme artistiche uniche, nate dall’esperienza della segregazione razziale e delle lotte per i diritti civili come le marce da Selma a Montgomery nel 1965. Anche il Sud degli Stati Uniti ha conosciuto il fuoco. Quello delle croci accese dal Ku Klux Klan, piantate nei cortili di notte, per ferire l’aria e lasciare segni nella carne della memoria. Ma c’è stato anche un fuoco che ha scaldato ferri di fortuna, che ha piegato lamiere per farne sculture o strumenti che potessero cantare. E poi un fuoco nascosto nelle gole, nel blues che saliva dalle piantagioni, nei cori del gospel che facevano tremare i banchi di legno. A volte era la terra stessa a incendiarsi, per disfarsi e ricominciare. Forse è questa brace che Hannah Collins ha continuato a cercare anche in We Will Walk: un calore che resta sotto, pronto a rifarsi fiamma.

E così, dopo l’intervallo delle parole, tutto si placa: il fuoco, la pagina e l’eco delle sue voci, si dissolvono insieme in cenere calda, in un pulviscolo che continua a vibrare, come un pensiero non detto, pronto a tornare brace al minimo soffio.

Cover: Hannah Collins Timanfaya – Between Volcanos / Entre Volcanes, 2024 Gelatin silver print 126 × 156 × 4 cm

Soy Fuego | Hannah Collins and the telluric language of memory

Text by Rita Selvaggio –

“All things are an exchange for fire, and fire for all things, as goods for gold and gold for goods.”

— Heraclitus, Fragment 90 (trans. G.S. Kirk, Heraclitus: The Cosmic Fragments, 1954)

Soy Fuego: this is the title of Hannah Collins’ latest exhibition in Madrid, at Prats Nogueras Blanchard (8 May–26 July 2025). It is more than a title: an invocation, a first-person incantation that immediately reveals the deeper impulse of the project—to erase the distance between the human body and the matter that burns, between memory that holds and flame that erases.

Collins, born in London in 1956 and shortlisted for the Turner Prize in 1993, is known for photographic installations and films that explore collective memory, cultural transformation, and the delicate frameworks of time. Here again, she shows her distinctive ability to bring together poetry, ethnographic observation, and critical insight. From her early monumental works that explored urban architectures and uninhabited spaces, to her long stays among Roma communities in Spain and Russia, her trajectory is marked by a gesture ever the same: to dwell at length, to allow herself to be altered by encounters with communities and landscapes, to listen to the stories that other worlds have to offer.

In this exhibition, Collins brings with her traces of the time spent as a guest among Indigenous communities for whom fire is not merely an instrument or ritual ornament, but a living creature with which to forge a relationship. In the large-scale photographs, in the whiteness of hand-moulded votive candles, in the fragments of drawings scattered across the space, one senses a bond that extends beyond the visual realm, embracing broader questions of ecological justice and the recognition of local knowledges. It is no accident that Collins recounts: “My task was to find a different memory, with positive associations, ways of relating to nature in balance, without being extractive. In the Amazon I had to relinquish my idea of control: it was a gradual, painstaking process, like learning to read a map I had not understood before. I saw the fire on the copal guide us through the night, but only later, staying with an elder shaman, did my perception of the plants and the land truly transform.”

It is in this act of yielding, in this allowing the fire to pass through her, that the work catches flame with meaning and becomes metamorphosis, more than document. This approach recalls Heraclitus’s notion of fire as “the ruler of all things,” the principle governing universal change, or Bachelard who, in Psychanalyse du feu, writes of fire as that which “penetrates us, transforms us, merges with the very substance of our dreams”. More recently, Federico Campagna, reflecting on ontology, myth, and the pluriverse (Technic and Magic: The Reconstruction of Reality, Bloomsbury Academic 2018), has shown how these archaic narratives and natural elements can become necessary counter-narratives in the face of the extractive machinery of global capitalism. Fire, in this sense, is also a political language, a subtle form of resistance.

Unlike many artists who still look upon the peoples of the Amazon with the eye of the anthropologist or the aesthetic tourist, Collins chooses to stay for long stretches, to share in modest gestures, to let herself be steeped in the slow rhythm of relationships. She states it plainly: “It cannot be that all one makes is a self-portrait. There must be a way to enter into relation with the other so that something happens. Society constantly changes in how it looks at and negotiates its environment. I am very hesitant. Sometimes I film from below, as I did when working with the Roma community at La Mina, to build the complexity I live in positive forms.”

In this hesitant reciprocity lies the ethical heart of her work: art as a fragile act, stretched taut between risk and trust, as matter that yields to touch, and to flame.

The landscape of the exhibition currently on view in Madrid stretches from the abandoned mines of Almería—cavities that once swallowed hands and sweat and now stand there empty, like parched mouths—to a quartz geode that harbours a secret of light embedded within the rock, and farther off to the Atacama, whose slender sky preserves traces of celestial bodies that have crossed the dark. Then there are fruits, leaves, small everyday gestures cast in wax and bronze, as if one wished to halt time in a caress that does not fade. Thus, within the space, the organic and the artificial convene, the ancestral and the contemporary meet. It is at this very crossing that Collins casts her gaze upon fire—not as threat, but as a necessary spark, a filament that binds together earth, body, and what remains of the sky.

This invocation of fire is not an isolated exception in Collins’s practice. Works such as Flaming Forest (2021), a large pigment photograph conceived for the same exhibition season as Soy Fuego, and the more intimate shots of In the Course of Time (12) Small Fire (1996), show how combustion, real or evoked, has long coursed through her imagination. In the former, the forest seems to hold back a secret glow, an incandescent state of suspension; in the latter, the small fire becomes a minimal yet absolute sign, a silent presence that burns and abides. These are flashes that return, in different ways, to weave the matter of the world with that of memory, as though the flame were always, at heart, a fragment of remembrance seeking a body in which to go on burning.

It is this same fire, this same telluric summons, that leads Collins to work on the subject of volcanoes for the XII Biennale of Lanzarote (27 January–5 April 2025). Curated by Alicia Chillida, her project is inscribed within a broader programme dedicated to the theme “Lanzarote Planetarium,” which explores ecology, sustainability, and the relationships between insular identity and trans-species imaginaries. Lanzarote becomes a natural planetarium, a volcanic island turned observatory of the sky and mirror of the Earth, a place where the rocky landscape tells of geological memory and connects to astronomy, to the cosmos, to nocturnal vision. By uniting earth and sky, volcanoes and stars, the project reflects on the origin and destiny of places and on how we come to inhabit them.

The project Between Volcanos / Entre Volcanes (2021–2025), a kind of sentimental planetarium, arose from Collins’s long research on the Paricutín volcano in Mexico, continued with fieldwork carried out in Lanzarote in 2024, among the landscapes of Timanfaya and La Corona, in collaboration with scholars, agronomists, and local artists. The result is an installation that combines large-format photographs, autobiographical texts written in charcoal directly onto the walls, and an interlacing of oral testimonies and scientific observations, restoring the volcano as a living, memorial entity, a site of geological and human metamorphoses.

Paricutín issued from a tear in the earth, all of a sudden. Not an ancient mountain, but a newborn of 1943, sprouting from a cornfield under the eyes of Dionisio Pulido, the farmer who first heard its rumble and then saw the smoke and soil churn, as if seized by an inner shudder. Within days it became a giant, devoured villages, leaving only a church steeple impaled in the lava, still today jutting up like a finger pointing to the sky. The Purépecha call it Parhíkutini, meaning “the place on the other side”: a beyond where the earth opens and remembers it is alive, where fire keeps stories that burn in a hushed voice. Perhaps this is what Collins sought in those craters: a landscape shedding its old skin to reveal what lies beneath, a ground that becomes an archive of ash and possibility. In Journey to the Centre of the Earth, published in Paris in 1864, Jules Verne invented an invisible tunnel beneath the continents, a corridor of fire and caverns linking the crater of Sneffels in Iceland to the mouths of Stromboli, two distant volcanoes speaking to each other through the warm belly of the planet. It is a tale of the earth as porous, penetrable body, hiding common roots beneath its crust. The protagonist, a young student of mineralogy, travels sideways through the earth, as one does with a friend, passing beneath the words. It is a journey that binds far-off craters, bringing into communication hearths separated by oceans. It is not mere adventure, but a way of saying that beneath the crust there are veins that touch without knowing, that fire keeps memory of the steps that once pressed upon it.

Because when the earth wills, it remembers all.

In this drift that brushes against geology to graze the raw edges of time, there opens a literary echo, an underground vein that ties Collins’s work to Verne’s tale—so vividly lit by Michel Serres in his essay “Jules Verne: la science et l’imaginaire,” gathered in Hermès II. L’interférence (1972). There, Serres reminds us that to descend into the earth is not merely to cross through space, but to slip back into a more ancient time, one pressed deep into the strata of stone, folded into the ground that hoards the memory of the world. It is a journey carried by a hunger that dirties the hands, a need to read the scrawls etched into mineral skin. So, Collins moves through volcanic lands, across fissures and craters, as if stepping over a threshold not only of place but of age. She slips beneath the crust, seeking not the quick flare of magma but something far older: a hushed archive where time thickens and knots itself, whispering through veins of cooled lava. One might say, then, that her works drop into the belly of the planet to probe its smouldering recollections, to leaf through, page by gritty page, the stories earth has been spelling out for ages, unrushed, in its coarse, stony tongue.”

Collins’s project moves along this imaginary furrow when it binds Mexico’s Paricutín to the volcanoes of Lanzarote, forging a secret alliance between distant landscapes. She does not set them side by side as an atlas might, but makes them resonate within one another, as if the lava bore memory, as if an eruption in one hemisphere might cause the ash to tremble in another. It is yet another way of saying that the earth harbours unknown kinships, and that fire, even when buried, remembers.

In this dialogue between Paricutín and the Canarian craters, Collins stitches together layered memories, reawakening myths of fire and storytelling practices that belong to communities far apart yet joined by the same telluric pulse. Here the earth breathes warm beneath its crust, and the craters are silent mouths that have known the flame; Collins moves among the black rocks with the same caution one uses when passing by a sleeping animal.

In The Volcano Lover, Susan Sontag lets a simple, almost disarming truth surface: “a volcano does not let itself be possessed. It lets itself be awaited”. Perhaps this is what Hannah Collins seeks: a long waiting, one that holds together ruin and rebirth, threat and seed. In her images, matter seems still alive, lingering there to promise yet another tremor; hers is a landscape that knows combustion, and for that reason continues to remember. The earth still smoulders beneath the surface, and the craters bear inscribed in their flesh the time of eruptions: it is in this geological substance that Collins rediscovers a primordial language in which molten matter becomes a mirror for our inner metamorphoses and our future conflagrations.

Along such an itinerary of ashes and glimmers, Soy Fuego does not present itself as a tale to be deciphered, but as a perceptual breach, an invitation to remain within the combustion, to listen to its crackling, to let the skin retain its scent. Here fire is not merely symbol or threat, but inner matter, a flash that runs through us, burning memory of what we have been and of what, perhaps, we might yet become.

To speak then of Hannah Collins’s books, from Finding, Transmitting, Receiving to The Fragile Feast, is to draw close to another hearth, where words and images hold tightly together, guarding what remains and offering it up to time. I find myself asking her: — what do you think is the political and poetic value of entrusting these materials to the printed page? And how does the book act differently from an exhibition in safeguarding and returning a collective memory? “Exhibitions are unique,” she replies, “an interaction with space at a given moment. Books instead establish a particular relationship between word and image, with a different link to time and to the audience. Politically they have a wider reach. That’s why I regret it when an exhibition is left without a book, as happened with “We Will Walk”, the show I curated on the American South. Later I worked with Doris Derby on “A Civil Rights Journey”, which went on to reach first place in some American charts: it was the book that needed to exist, and I am proud to have brought it into being.”

We Will Walk, co-curated with Paul Goodwin and presented at Turner Contemporary in Margate (7 Feb – 3 May 2020), focused on Alabama and the African American communities there who developed unique artistic forms, born from the experience of racial segregation and the struggles for civil rights, like the marches from Selma to Montgomery in 1965. The American South too has known fire. That of the crosses set ablaze by the Ku Klux Klan, planted in yards by night to wound the air and leave scars in the flesh of memory. But there was also a fire that heated makeshift irons, that bent scrap into sculptures or instruments that could sing. And then a fire hidden in the throats, in the blues rising from the plantations, in the gospel choirs that made wooden pews quake. Sometimes it was the earth itself that caught fire, to break apart and begin again. Perhaps it is this ember that Hannah Collins has kept seeking even in We Will Walk: a heat that stays beneath, ready to flare up once more.

And so, after the interval of words, all falls silent: the fire, the page, and the echo of its voices dissolve together into warm ash, into a quivering dust that does not settle, but hovers — like a thought withheld, smouldering just beneath the breath, waiting for the faintest stir to kindle it back into flame.

Cover: Hannah Collins Timanfaya – Between Volcanos / Entre Volcanes, 2024 Gelatin silver print 126 × 156 × 4 cm