English version below

Season Ending (The day of forever) è il video realizzato dallo scrittore e critico Shumon Basar per Finite Rants, progetto on-line della Fondazione Prada – curato da Luigi Alberto Cippini e Niccolò Gravina – che ha visto avvicendarsi una serie di cineasti e intellettuali alle prese con dei saggi visuali atti a sondare questioni sociali, politiche e culturali emerse nel contemporaneo.

Daniela Zangrando ne parla in questa intervista con l’autore.

Daniela Zangrando:Season Ending (The day of forever) sembra prima di tutto un ragionamento. Puntuale e sofisticato. Su un’iperproduzione e un’eccedenza di immagini, certo. Ma soprattutto sull’oggi. Me ne racconti la genesi e il processo?

Shumon Basar: Tutto inizia con la premessa della piattaforma Finite Rants, iniziata alcuni mesi dopo l’inizio della pandemia nel 2020. Luigi Cippini e Niccolò Gravini sono interessati ad estendere e aggiornare la tradizione del “saggio visivo” o “saggio cinematografico”. E questo è un genere estremamente importante per me. Un film come Sans Soleil di Chris Marker e la produzione di Jean-Luc Godard in collaborazione con Anne-Marie Mieville fin dalla metà degli anni ’70 sono il culmine della sintesi di parola (scritta e parlata), immagine e suono. Dato che io dovevo essere l’ultimo capitolo della prima stagione di Finite Rants, e dato che era la fine del 2020 quando ho iniziato a lavorare, mi è venuta in mente questa espressione: “Season ending”, finale di stagione. È un’espressione che è ora familiare a tutti quelli che macinano serie su Netflix. Il 2020 ha obbligato improvvisamente tutto il mondo a vivere in un reality apocalittico. La gente scherzava, magari nervosamente, su come questa era la nuova “fine”, “This is the [new] End”. Ecco perché ho pensato alla fantascienza durante tutta la pandemia. Perché molti racconti fantascientifici sono ambientati in un immaginario “dopo”, in cui un cataclisma crea un nuovo ordine nella realtà. Nel nostro prolungato sbandamento all’interno della pandemia, ora già da un anno, e probabilmente ancora per anni, si sogna un “dopo” che ci permetterà di tornare al “prima”. Tuttavia una fantasia come questa non è altro che la fantasia della “fine”.

Daniela Zangrando: Mi hai detto di essere interessato ai brevi screenshot postati nelle storie di chi ha visto il video. Quali strappi sono stati fatti? Hanno messo in rilievo qualcosa in comune?

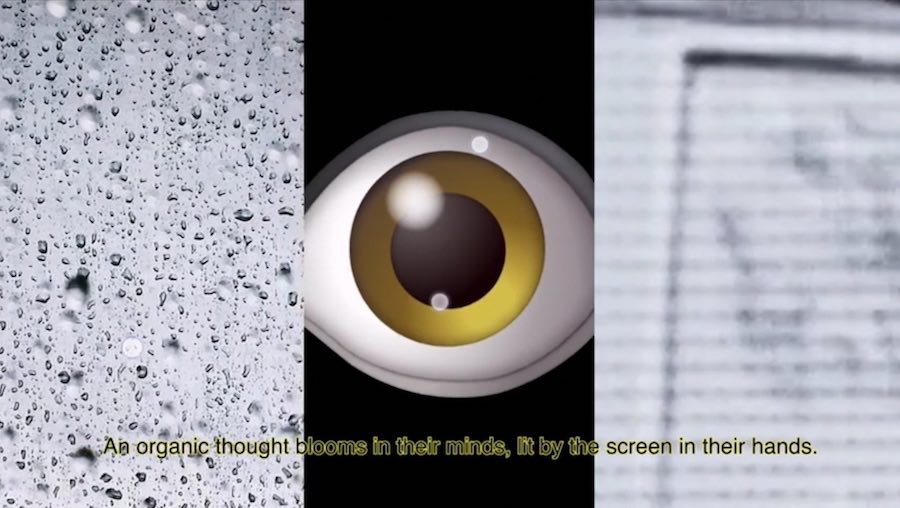

Shumon Basar: Ho una conoscenza ragionevolmente ampia della storia del cinema, ma non sono un regista. Quindi ho lavorato a stretto contatto con il video-editor milanese Francesco Tosini, che ha contribuito moltissimo alle prodezze tecniche del film. La gente commenta che i contenuti da me postati su instagram — che sono quasi esclusivamente sotto forma di Storie — sono una specie di macchina narrativa. Li uso per prendere appunti sul presente e registrare quello che leggo, vedo, ascolto. Richard Buckminster Fuller — visionario architetto, ingegnere e inventore — realizzò una cosa che si chiamava “Dymaxion Chronofile” in cui “creò un enorme scrapbook in cui documentò la propria vita ogni 15 minuti dal 1920 al 1983”. Non è forse quello che stiamo facendo ora se siamo neurologicamente collegati con il tasto “Storia” dei nostri cellulari? Volevo creare un nuovo tipo di fantascienza sul 2020, allora aveva senso partire dal materiale visivo che avevo già elaborato nelle mie Storie, attorno al quale ne ho raccolto poi dell’altro. Quindi la maggior parte del mio repertorio ha una durata estremamente ridotta, il che porta a un’estetica discontinua, stroboscopica, alternandosi fra un formato orizzontale e uno verticale, in sequenze e stratificazioni realizzate da Francesco in modo molto ricercato.

Daniela Zangrando: Lavoro a questa intervista proprio nel giorno di San Valentino. Il mio pensiero va a Mia e Abdullah, l’ultima coppia. Dove si sono conosciuti? Sono reali? Cosa ne sarà di loro?

Shumon Basar: Buon San Valentino Parte Seconda! Mia e Abdullah… beh, sono fissato con la figura della coppia come unità fondante dello storytelling fin da quando ho scritto la tesi di laurea su Pierrot le fou (1965). Godard mette insieme questa coppia bizzarra ed esplosiva — Ferdinand e Marianne — che sembra in grado di incarnare quasi tutto. In particolare, gli opposti: cerebrale e intuitivo, poeta e criminale; aria e mare. Quindi continuavo a tornare al formato della coppia, come un drogato di romanticismo, e in Season Ending ho immaginato una coppia che credeva di essere l’ultima coppia sulla terra nel momento finale della storia della terra. Mia e Abdullah, anche se soltanto “due”, in questo momento, non contengono solo moltitudini, ma la portata stessa della storia e del futuro dell’umanità. Cosa accadrà loro? Magari se un giorno farò un sequel ti farò sapere…

Daniela Zangrando: Qualche giorno fa Stefano Zaniboni, studioso e collezionista di vinili, ha postato sui suoi canali social la foto di un gruppo di bambini intenti ad ascoltare il canto degli uccelli. Te la allego. Credo sia molto incisiva. Mia e Abdullah li ho immaginati così … perché non avevano mai sentito prima il canto degli uccelli?

Shumon Basar: Città metropolitane ad alta densità — come Milano o Guangzhou — uccidono le stelle a causa dell’eccessiva quantità di luce elettrica e spesso uccidono i suoni della natura a causa del traffico incessante e del brusio dell’attività umana. All’inizio del lockdown — che ho osservato dal 56° piano di un grattacielo di Dubai — era veramente apocalittico vedere l’intera città svuotata dalle persone e dai veicoli, per settimane e settimane. Una città che normalmente è rumorosa 24 ore su 24 era immersa in un silenzio mortale. E in quel silenzio… si poteva sentire il canto degli uccelli. Ci sono stati anche avvistamenti, in molte città, di caprioli e altri animali che si avventuravano nei centri urbani. Questo è un tropo familiare della fantascienza — la natura che ritorna dopo la scomparsa dell’umanità — che è stato anche riassunto dal meme del primo Coronacene: “Il virus siamo noi”.

Daniela Zangrando: La fine. I finali, lo dici proprio tu, possono offrire una promessa di salvezza, di redenzione, persino di libertà.

D’altro canto, pare che vivere faccia morire, come dice un personaggio dell’ultimo libro della scrittrice Chiara Valerio, “Il cuore non si vede”.

Shumon Basar: L’idea della “fine” ha un qualcosa di seducente. Per esempio, già da un secolo l’arte occidentale parla di “fine della pittura”. Eppure la pittura sopravvive e anzi domina il mercato dell’arte. Non è più una contraddizione affermare che qualcosa è finito mentre quella stessa cosa sembra continuare a vivere. È una specie di condizione quantica: essere vivi e morti allo stesso tempo. Forse non è un caso che uno dei movimenti pittorici più produttivi degli ultimi tempi si sia chiamato “formalismo zombie.” Per la teoria culturale, il “postmodernismo” ha dato origine a un’aporia dopo la quale abbiamo fatto molti tentativi disperati di dare un nome all’era storica successiva (“altermoderno,” “off-modern,” “metamoderno”). E poi non c’è nulla di realmente “nuovo” che possa emergere senza porre fine a ciò che lo ha preceduto. In quanto tale, “la Fine” rappresenta anche una liberazione, come il mito del diluvio universale. Eppure gli esseri umani fantasticano sull’immortalità. Ingannare la Fine. Continuare per sempre.

Daniela Zangrando: Il tuo video, riprendendo l’inizio di questa intervista, è immerso nel vivere di questi nostri giorni. Ne è assorbito. Lo trovo schietto, e senza alcuna retorica.

Con la stessa disposizione vorrei tu rispondessi a questa domanda: come sta cambiando il tuo stare al mondo, oggi? Cosa sta succedendo allo Shumon Basar curatore, editore, scrittore, ma soprattutto, uomo? Che ne è del suo cervello pre-Coronavirus?

Shumon Basar: Una delle cose più difficili è misurare il cambiamento che ti sta accadendo mentre ti sta accadendo. Ecco perché la foto che hai fatto 10 secondi fa è ipernormale, ma fra un anno, o fra 10 anni, sembrerà strana. La pandemia ha anticipato cambiamenti dei prossimi due o tre decenni nel presente di adesso. Molte persone sono crollate di fronte a questi cambiamenti. Per me, prima del Covid, il movimento era significato. Tendevo a vivere e lavorare fra un continente e l’altro, un prodotto di quella storia di globalizzazione “senza attrito”. Quando questo è diventato impossibile il mio cervello, anzi la mia anima, non sapeva come gestire la situazione. È un male molto privilegiato, certo, e non si può annoverare in mezzo alle tragedie di milioni e miliardi di persone. Ma nonostante tutto ciò che ha portato questa era di shock schermoabilitante — dalla videoconferenza alla videosofferenza — io rimango un forte sostenitore di tutto ciò che non è sullo schermo: l’aria sottile e frizzante, il frémito dei corpi nello spazio condiviso, il buio coinvolgente del cinema.

Daniela Zangrando: Guardare Season Ending (The day of forever) mi fa anche pensare all’idea che stai sviluppando, con Douglas Coupland e Hans Ulrich Obrist, di “Extreme Self”. Cosa indica questa espressione?

Shumon Basar: Non so tu, ma ogni mattina io mi sveglio e trovo qualcosa di completamente nuovo. Quello che davo per scontato ieri, oggi non posso più darlo per scontato. E la pandemia ha reso questa sensazione ancora più estrema. Le cose che pensavamo fossero delle costanti, improvvisamente sono impossibili o complicate. La pandemia ci ha fatto esistere sullo schermo, come flussi di dati, come messaggi vocali, come emoji espressivi. È possibile tornare indietro? Sembra assurdo, ora, parlare di “prima vita” (quella fisica) e “second life”, “seconda vita” (quella digitale), come se fossero separate. “L’Extreme Self” si concentra su come il nostro senso dell’essere individui o collettivi e folle sta cambiando forma a causa di queste rotture nel tessuto della realtà. Cosa siamo diventati? Cosa stiamo diventando?

Daniela Zangrando: Penso che il 2020 abbia rappresentato un momento di rottura e messa in discussione del pensiero. Citandoti, “Era questa la fine?”

Shumon Basar: Ogni fine poi diventa l’inizio di qualcos’altro. Non sapremo che cos’è per un po’ di tempo. L’attuale situazione lascerà effetti duraturi all’interno dei nostri cervelli, sulla superficie del pianeta, nell’ordine geopolitico per il resto del secolo. Vale la pena ricordare che le società tradizionali, premoderne, intendevano l’ordine del tempo in modo molto diverso. Noi tendenzialmente pensiamo che il tempo scorra in una sorta di linea retta, dal passato, attraverso il presente e verso il futuro. Ma nella tradizione il tempo era ciclico, quello che Mircea Eliade chiamava “Il mito dell’eterno ritorno.” Era questa la fine? O era quello l’inizio?

Traduzione di Giulia Galvan.

Shumon Basar è scrittore, editore e curatore.

Daniela Zangrando è curatrice indipendente e direttrice del Museo Burel

SEASON ENDING (THE DAY OF FOREVER)

Interview with Shumon Basar

Season Ending (The day of forever) is the video created by writer and critic Shumon Basar for Finite Rants, an on-line project by Fondazione Prada –curated by Luigi Alberto Cippini and Niccolò Gravina – which has involved a series of filmmakers and intellectuals, working on visual pieces in order to investigate the social, political, and cultural matters that have come to light in the contemporary world.

Daniela Zangrando talks about it with the author.

Daniela Zangrando: Season Ending (The day of forever) looks first of all like an accurate and sophisticated line of thought. About a hyper production and an excess of images, for sure. But especially on the contemporary world. Can you tell me about the origin and creative process of the piece?

Shumon Basar: It really starts with the whole premise of the Finite Rants platform, which began a few months into the pandemic in 2020. Luigi Cippini and Niccolo Gravini are interested in extending and updating the tradition of the “visual essay,” or, “film essay.” This happens to be an extremely important genre to me. A film like Sans Soleil by Chris Marker, and the output of Jean-Luc Godard in collaboration with Anne-Marie Mieville since the mid 1970s, are highpoints in the synthesis of word (written and spoken), image and sound. As I was to be the end of this first season of Finite Rants, and it was the end of 2020 when I set to work, this phrase came to my mind: “Season ending.” It’s now familiar to Netflix binge watchers. The year 2020 suddenly forced the entire world to star in an apocalypse reality TV show. People joked — nervously, maybe — about how this was “the End.” Which is why I have been thinking about science fiction throughout the pandemic. For many science fiction stories take place in some speculative “after,” where a cataclysmic event reorders reality. Our extended lurch into the pandemic — now one year long, and possibly years more to come — dreams of an “after” that would allow us to go back to “before.” However, such a fantasy is just that: the fantasy of “the End.”

Daniela Zangrando: You told me you are interested in the short screenshots and fragments that the ones who saw the video posted in their Instagram stories. Which parts have they torn away? Did they share anything in what they highlighted?

Shumon Basar: I have a reasonably vast knowledge of the history of cinema; but I am no filmmaker. So, I worked closely with the Milanese editor, Francesco Tosini, who has contributed greatly to the technical prowess of the film. People have commented that my Instagram content — which has been almost exclusively in the Stories format — is a kind of narrative machine. I use it to annotate the present, and record what I am reading, seeing, hearing. Richard Buckminster Fuller — the visionary architect, engineer and inventor — produced something called the “Dymaxion Chronofile” where “he created a very large scrapbook in which he documented his life every 15 minutes from 1920 to 1983.” Is this not what we now do if we are neurologically linked to the “Story” button on our phones? Since I wanted to make a new kind of science fiction about 2020, then, it made sense to start with the visual material I had already processed on my Stories, around which I then collected more. It also means that most of my footage is extremely short in duration. This leads to the staccato, stroboscopic aesthetic, that switches between landscape and portrait mode, which Francesco has so exquisitely sequenced and layered.

Daniela Zangrando: I’m working on our interview on Valentine’s Day. My thoughts go to Mia and Abdullah, the last couple. Where did they meet? Are they real? What will happen to them?

Shumon Basar: Happy Valentine’s Day Redux! Mia and Abdullah… well, I’ve been fixated with the figure of the couple as a foundational unit of story telling ever since I wrote my university dissertation on Pierrot le fou (1965). Godard sets up this explosively odd couple — Ferdinand and Marianne — who seem to be able to embody almost everything. In particular, opposites: cerebral vs intuitive; poet vs gangster; air vs sea. So, I’ve returned to the couple format again and again, like a Romantic addict, and in Season Ending, I pictured a couple who believed they were the last couple on earth at the final moments of earth. Mia and Abdullah, although only “two,” for this moment, not only contain multitudes, but, the entire scope of human history and futurity. What will happen to them? Maybe if I make a sequel one day, I will let you know…

Daniela Zangrando: A few days ago Stefano Zaniboni, a researcher and vinyls’ collector, posted on his social profiles a photo of children all concentrated in listening to the birds sing. I am attaching it. I think it is very incisive. I imagined Mia and Adbullah being like this group of children… Why hadn’t they ever heard the birds sing before?

Shumon Basar: Dense, metropolitan cities — like Milan or Guangzhou — kill the stars with their excessive amounts of electric light, and, often kill the sounds of nature, due to the incessant traffic and hum of human activity. At the beginning of the lockdown — which I observed from the 56th floor of a skyscraper in Dubai — it was genuinely apocalyptic to see the entire city voided of people and vehicles, for weeks on end. A city that is normally noisy 24 hours a day became deadly silent. And in that silence… you could hear bird song. There were also sightings in several cities of deer and other animals now venturing into urban centres. This is a familiar trope of sci-fi — nature returns after mankind vanishes — which was also encapsulated in the early Coronacene meme: “We are the virus.”

Daniela Zangrando: The end. The endings, you say so, can offer a promise of salvation, redemption, even freedom. On the other hand, it looks like living will make you die, like one of the characters of “Il cuore non si vede” (You don’t see one’s heart) says, that is the latest book written by writer Chiara Valerio.

Shumon Basar: There is a seductiveness to the idea of “the End.” For example, “The End of Painting” has been going on in Western art for over a century now. And yet, painting still survives, and indeed, dominates the art market. It’s no longer a contradiction to claim that something has ended, while, that very thing also seems to live on. It’s a kind of quantum condition: to be both alive and dead at the same time. Maybe it’s no coincidence that one of the most profitable painting movements in recent times was called “Zombie Formalism.” For cultural theory, “post-modernism” provided an aporia, after which, we have had lots of desperate attempts to name the succeeding historic era (“alter-modern,” “off-modern,” “meta-modern”). Also, nothing truly “new” can emerge without the end of that which precedes it. As such, “the End” is also a great clearing, like the flood myth. And yet, humans also still fantasise about immortality. Cheating the End. Continuing forever.

Daniela Zangrando: To get back to where we started this interview, your video is submerged in the life of these days of ours. It is totally absorbed by them. I find that sincere, and free of any sort of rhetoric. With the same attitude, I would like you to answer this question: how is your being in the world changing today? What is happening to Shumon Basar – a curator, publisher, writer, and above all, a man? What about his pre-Coronavirus brain?

Shumon Basar: One of the most difficult things is to measure the change that is happening to you as change is happening to you. It’s why a photo you took 10 seconds ago is hyper-normal, but, in a year’s time, or 10 year’s time, it will look strange. The pandemic has brought forward changes from the next two to three decades into our current present. Many people are collapsed under these changes. For me, pre-Covid, movement was meaning. I have tended to live and work across continents, a product of that history of “frictionless” globalisation. When this became impossible, my brain — my soul, even — didn’t know how to cope. It’s a very privileged malady, of course, and not one that ranks on any meaningful scoreboard of tragedy that has struck millions and billions. But for all that this screen-empowered shock era has brought us — from Zoom to doom — I remain a strong advocate for everything that isn’t the screen: thin crisp air, the frisson of bodies in shared space, the absorbing dark of the cinema.

Daniela Zangrando: Watching Season Ending (The day of forever) also makes me think about the idea you have been developing, with Douglas Coupland and Hans Ulrich Obrist, the idea of an “Extreme self”. What does this expression indicate?

Shumon Basar: I don’t know about you, but I wake up every morning to something entirely new. What I took for granted yesterday, I can’t anymore today. And then the pandemic made this feeling even more extreme. Things that we thought were constants are suddenly impossible or complicated. The pandemic has made us exist on screens, as data streams, as voice-notes, as expressive emoji. Is there any going back? It seems ridiculous, now, to talk about “first life” (the physical) and “second life” (the digital) as though they are separated anymore. “The Extreme Self” is interested in how our sense of being individuals, or collectives and crowds, are morphing because of these ruptures in the fabric of reality. What have we become? What are we turning into?

Daniela Zangrando: I think 2020 stood for a moment of rupture, a chasm of thought. Quoting you: “Was that the end?”

Shumon Basar: Every end later turns out to be the beginning of something else. We won’t know what this is for some time. The present condition will leave lasting effects, on the insides of our brains, on the surface of the planet, on the geopolitical order of the rest of this century. It’s worth reminding that traditional, pre-modern societies had a very different understanding of the order of time. We tend to think of time flowing in some kind of straight line, from the past, through the present, to the future. But traditional understanding of time was cyclical, what Mircea Eliade called, “The Myth of the Eternal Return.” Was that the end? Or was that the start?

Translated by Giulia Galvan.

Shumon Basar is a writer, publisher, and curator.

Daniela Zangrando is an independent curator as well as the director of Museo Burel.