English version below —

Venezia è una città che più di qualunque altra sembra fatta di sottrazioni e pause, di ciò che manca e di ciò che sfugge. Un luogo in cui l’acqua è muro e strada insieme, dove persino il tempo si allaga e si fa lento battito di remi. Josif Brodsky, che la scelse come rifugio invernale, scrisse che Venezia è «una cartolina inviata da nessun luogo a nessun altro luogo» (Fondamenta degli Incurabili, 1992): un messaggio senza mittente né destinatario, che tuttavia giunge puntuale al cuore di chi la attraversa. Camminando per Dorsoduro o per qualsiasi altro sestiere, si avverte una sensazione simile a quella di una lettera mai spedita, di un discorso che si arresta a metà frase. Qui i muri trasudano storie che non vogliono essere raccontate tutte in una volta, ma si fanno confidenze a bassa voce. Il silenzio non è un vuoto, bensì un’eco che rimbalza tra calli strette e cortili improvvisi, moltiplicandosi sui canali come su uno specchio frantumato. E forse è proprio questa la cifra più autentica di Venezia: non tanto l’opulenza delle facciate o la solennità delle chiese, quanto la sua fragile consistenza, la tenace precarietà che la regge sopra l’acqua, come un’ipotesi di città sempre prossima a disfarsi.

A Venezia l’acqua non è soltanto sfondo, ma materia attiva che modella la città. Ogni palazzo si regge su pali conficcati nel fango, respira la marea, si lascia corrodere dalla salsedine. L’architettura qui è un patto fragile tra il peso della pietra e la cedevolezza dell’acqua, un equilibrio precario che rinnova ogni giorno il rischio della rovina. Abitare Venezia significa dunque accettare che il tempo e la laguna siano architetti invisibili, che incidono, scolpiscono, riplasmano senza tregua.

C’è un punto di Venezia, tra le pieghe meno clamorose ma più dense di segreti, che da secoli ospita studi di artisti, botteghe, dimore silenziose lambite da canali stretti come vene d’acqua. Il Sestiere di Dorsoduro fu per secoli il quartiere dove i mercanti scaricavano spezie e panni tinti, tra magazzini odorosi di canfora e banchine brulicanti di dialetti. Qui si accamparono botteghe di pittori, si aprirono scuole di disegno, e piccole tipografie stampavano libretti di preghiere o di melodrammi. La vitalità commerciale si mescolava a una quiete domestica fatta di panni stesi sui ponti e cortili segreti. Ancora oggi, passeggiando per queste calli, sembra di calpestare una geografia di mestieri, tracce di vite operose che si sono sedimentate come il limo tra le fondamenta. Dorsoduro, così chiamato perché sorgeva su un terreno relativamente solido rispetto alle paludi circostanti — un dosso duro — nei secoli ha accolto anche conventi, palazzi patrizi, scali mercantili. In questo tessuto urbano denso di memorie sovrapposte, Nicoletta Fiorucci Foundation ha trovato la sua dimora in un edificio del XV secolo. Fondata per sostenere l’arte contemporanea più sperimentale, ecologica, femminista e decoloniale, la Fondazione ha inaugurato qui la sua sede veneziana con l’intento di trasformare questo luogo in una piattaforma viva, permeabile, abitabile. Un palazzo che porta su di sé le stratificazioni tipiche della città: fu nobile residenza rinascimentale, dove forse l’eco di feste e salotti si aggrappa ancora ai soffitti alti, poi atelier di Ettore Tito, pittore che amava dipingere volti e corpi come se galleggiassero nell’aria densa di Venezia, figure uscite da un sogno di sale. Di quel passaggio restano forse piccole ombre nei muri, impronte leggere che si confondono con la polvere. Più tardi fu ambulatorio medico, stanze che hanno visto corpi feriti, mani febbrili, voci di premura o di timore, lasciando dietro un odore di antisettico misto a speranza. Oggi è spazio per l’arte che accoglie altre fragilità, altri tentativi di raccontare ciò che trema, con opere che si fanno varco e domande infilate tra le pareti. Una casa che, come molte a Venezia, non smette di trasformarsi, mutando la propria identità attraverso gli strati del tempo.

Ed è in questo palazzo di Dorsoduro che Tolia Astakhishvili, artista georgiana nata a Tbilisi nel 1974, ha scelto di “abitare”. Abitare non è solo occupare uno spazio, ma lasciare che esso ci trasformi. Heidegger direbbe che abitare è «custodire l’essere», prendersi cura di ciò che ci eccede. Astakhishvili “ ha abitato” nel senso più radicale: si è lasciata contaminare dal ritmo delle stanze, dalla polvere, dai cigolii notturni, permettendo che la casa entrasse in lei tanto quanto lei entrava nella casa. Il risultato è un incontro tra vulnerabilità reciproche. Per mesi ha vissuto tra queste mura, muovendosi come un’ospite attenta, lasciando che il palazzo parlasse attraverso i suoi stessi cedimenti. Ha tolto intonaci, aperto passaggi, esposto tubature, modificato la disposizione di pareti e soglie, inserito specchi e materiali recuperati. Ha fatto sì che il passato e il presente della casa si intrecciassero in un dialogo fragile, dove ogni stanza custodisce respiri inquieti. Non sorprende che proprio Venezia, città-palinsesto per eccellenza, sia divenuta teatro di questa operazione. Qui l’architettura si mostra da sempre come un organismo rizomatico: una rete di isole, canali, ponti, bricole, che cresce e si ramifica orizzontalmente, senza un centro dominante. Le case veneziane sono palinsesti di pietra e acqua, nate da continue aggiunte, innesti, rialzamenti, riconversioni. Un modello perfetto per comprendere la natura di questo progetto.

La pratica di Tolia Astakhishvili si muove sempre in bilico: tra costruzione e rovina, tra intimità ed esposizione, tra il gesto dell’artista e la risposta muta dell’architettura.

Il suo intervento sui luoghi non è mai puramente estetico: è un atto di svelamento radicale, di prossimità non protetta. In questa sede spoglia i muri come se staccasse una pelle, lasciando affiorare vene di tubature, cicatrici d’intonaco, memorie d’acqua.

Ma al tempo stesso ricuce il luogo con presenze minime, frammenti. Come a dire che la casa –lo spazio– non è mai un contenitore neutro, ma un corpo abitato, vulnerabile, caduco.

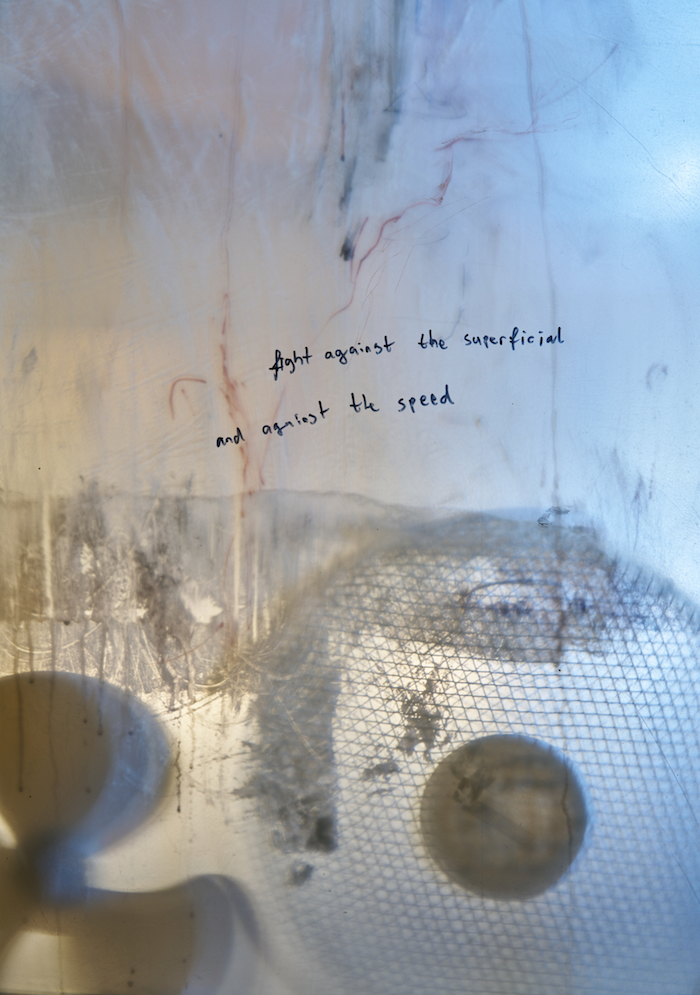

Questa poetica dell’abitare precario si riflette anche nei suoi disegni e dipinti, spesso installati come presenze incerte, mimetizzate sulle pareti o semi-occultate, che costringono chi guarda a un atto di ricerca, a un rallentamento percettivo.

Sono apparizioni che parlano di genealogie, di fughe e ritorni, ma sempre in forma allusiva: tracce più che racconti, impronte che non chiedono di farsi narrazione lineare.

to love and devour, titolo di questo intervento site-specific, è prima di tutto un gesto di abbandono dell’idea tradizionale di mostra personale.

Curato da Hans Ulrich Obrist, il progetto si configura come dispositivo discorsivo e relazionale, culminato nella pubblicazione di un libro d’artista omonimo, edito da Lenz Press, che lo documenta. Non è un dettaglio secondario che to love and devour prenda forma proprio durante la Biennale di Architettura di Venezia, quasi in controcanto silenzioso. Se la Biennale indaga l’architettura come progetto e struttura, Tolia Astakhishvili ne mette in discussione l’idea stessa, portando alla luce la soglia, la rovina, il fragile. Non un padiglione, ma un organismo. Non una visione, ma un’adesione al luogo. La mostra si struttura come una trama mobile: non forza percorsi, ma lascia che le cose accadano — che opere, architettura e memorie si incontrino, si disturbino, si trasformino a vicenda. Non c’è una sequenza da seguire, né un filo narrativo a guidare: è il palazzo stesso che diventa corpo poroso, attraversato da presenze che sembrano germogliare dalle sue ferite. Astakhishvili ha infatti coinvolto altri artisti a questo esperimento, non come aggiunta ma come prolungamento organico del proprio gesto: ciò che ne risulta non è una somma, ma un campo d’intensità condivise. Un rizoma che si propaga per connessioni orizzontali, dove le identità si toccano, si mescolano, si confondono, dove ognuno aggiunge un ramo, un battito, una deviazione che si fonde con il respiro segreto delle stanze.

Attraversando le stanze, Nails (2025) di Ketuta Alexi-Meskhishvili sfiora la retina come una reminiscenza infantile: una stampa inkjet sospesa su cotone, i cui contorni sembrano liquefarsi mentre la luce ne attraversa la superficie, catturata per un istante e subito rilasciata. È una leggerezza che non si ripiega su sé stessa, ma trova un’eco in Taste (Snoring and the Sound of Pigeons), un’installazione scultorea con un intervento sonoro di Dylan Peirce al suo interno. Il paesaggio sonoro ambientale di Dylan è una topografia acustica dei molteplici canali veneziani che modulano e mediano il suono. L’opera è costruita da registrazioni catturate a diversi livelli della città – ad esempio, la vita di strada registrata attraverso un grande condotto metallico, combinata con il rumore di ventilatori e tubature. L’intera scultura diventa un organismo sonoro, che vibra oltre la sua forma fisica.

Il video From Here to There (Sidewalks) presenta anch’esso un paesaggio sonoro di Dylan ed estende questa logica dello spostamento: un montaggio frammentario, dettagli marginali, passaggi ripetuti che generano la sensazione di una camminata sospesa, come se l’opera stessa fosse un viaggio senza destinazione.

È all’interno di questa trama di apparizioni sottili che prende forma il lavoro di Thea Djordjadze, come se l’assenza fosse la naturale prosecuzione di un’immagine che resiste alla presa. In Untitled (2020, 4 oggetti metallici, ciascuno 20,5 × 12 × 12 cm), i piccoli oggetti vicini agiscono come segni minimi di resistenza, frammenti di una sorta di archeologia domestica.

E ancora, quasi a sottolineare questa logica di precarietà, Zurab Astakhishvili — il padre di Tolia — lascia appunti che sembrano trattenere il tempo attraverso collage su finestre e un modello architettonico (I Can’t Imagine How I Can Die If I’m So Alive, 2025; Suddenly the World Became Loud II, 2024), frammenti affettivi appuntati sulla vulnerabilità della materia. I collage sono esposti in equilibrio instabile: a coprire le superfici di una scatola da scarpe rovesciata e di una mensola posata senza funzione sul pavimento.

Così come gli appunti di Zurab restano sospesi tra progetto e rovina, anche Heike Gallmeier lavora lungo una soglia fragile: in Prospective Dream (2010, C-print analogico su Alu-Dibond, incorniciato, 170 × 220 cm), la fotografia diventa al tempo stesso passaggio e frammento. La composizione si dispiega come un collage tridimensionale ricostruito e fotografato: frammenti di architettura, nature morte improvvisate, fondali scenici che sembrano oscillare tra immagine e realtà. Lo scatto diventa così documento e illusione insieme. Su questo terreno instabile si posa il lavoro di Rafik Greiss, the right to rest and leisure I, II (C-print su carta giapponese, collage, 50 × 60 cm; 60 × 75 cm). Nei suoi interventi, corpi e frammenti fotografici assemblati su fogli delicati, quasi traslucidi, sembrano affiorare e dissolversi, trattenuti in sospensione tra apparizione e cancellazione.

Il lavoro collaborativo di James Richards e Tolia Our Friends in the Audience (2024, stampa, marouflage su tela, 200 × 130 cm) è una stampa sussurrata, una superficie assorbente più vicina a un’ombra inscritta che a un’immagine compiuta, mentre I Remember (Depth of Flattened Cruelty,2023), un video HD, 10:16 min, realizzato con Tolia Astakhishvili) respira con le pareti, proiettando immagini rarefatte che sembrano dissolversi nei materiali stessi della stanza, fondendosi con i suoi rivestimenti. Il lavoro di Maka Sanadze sembra raccogliere proprio ciò che rimane in sospeso da questi passaggi: segni effimeri, frammenti intimi, tracce di un linguaggio che sfugge. Le sue opere (Untitled, pagine di riviste trattate, 38 × 29 cm; 46 × 36,5 cm) emergono come superfici logore, macchiate, a metà tra reliquia e detrito — pagine strappate che portano l’impronta del tempo, iscrizioni sopravvissute solo in frammenti. Lo stesso principio di precarietà abita il palazzo in altri interventi, che si presentano come modificazioni organiche piuttosto che come opere isolate: un bagno ridotto a struttura scheletrica (My Emptiness, 2025, pareti sezionate, tubi scavati, vasca), simile a un corpo spogliato in cui le tubature si intrecciano come ossa esposte; un modello architettonico nascosto in uno spazio di servizio (House of Mending, 2024–2025, cartone, cartapesta, bicchieri, adesivi, piumone, water, scatola con polvere, vetro), disseminato di materiali umili e residui; una parete divisoria in cartongesso appoggiata a una parete nuda (When the Others Are Within Us, 2025, cartongesso, gesso, caffè, inchiostro, neve artificiale, 980 × 266 cm), che si rivela come barriera temporanea; disegni incorniciati in plexiglass (A Timeline with Physical Attributes, 2025, carta, matita, inchiostro, pastello, 31 × 22 cm ciascuno), disposti quasi come ex-voto o mappe provvisorie.

Tutto si tiene sul filo: tra il visibile e il rimosso, tra l’opera e l’eco, tra la costruzione e la rovina. Come accade nelle case abbandonate dagli assenti ma abitate dai ricordi, qui l’arte non irrompe, ma vibra sottopelle, come un pensiero che tarda a disfarsi. Entra nello sguardo come la polvere: lenta, leggera, inesorabile. E ci ricorda che anche la visione può essere un atto fragile, che esige rispetto, come quando si entra nella stanza di qualcuno che non c’è più, ma il cui respiro è ancora lì.

Il concetto di rizoma, così come lo immaginavano Deleuze e Guattari, si fa qui metodo curatoriale e forma dell’esperienza: un sistema che rifiuta gerarchie, strutture centrali, firme univoche. Non esiste l’Uno che si divide, né il Molteplice che si riconduce a un’origine. Esiste un molteplice che cambia dimensione, che si espande in modo non lineare, che cresce per innesti, scarti, contaminazioni. Così anche la soggettività autoriale si dissolve: non c’è una sola voce a guidare, ma una coralità che si genera per attrito, per ascolto, per esposizione.

C’è una voce che si espone senza scudo, come la descrive Adriana Cavarero: fragile, irripetibile, incarnata. Una voce che non precede il corpo, ma lo traduce in suono, rendendo udibile la sua unicità vulnerabile. E c’è una scrittura che trema sul margine, come quella di Anne Carson: voce che non si difende, che vibra nella fenditura e, proprio per questo, riesce a toccare. Le stanze scarnificate di Astakhishvili — con le tubature scoperte, le pareti spellate, gli oggetti come resti — sono come corde vocali mute dell’edificio: non parlano, ma sussurrano da sotto la pelle. Mostrare queste ferite non è un gesto compiaciuto, ma una presa di posizione: un atto politico che si oppone alla levigatezza, alla prestazione, alla forma chiusa. Qui, nella crepa, nella sospensione, si riconosce la verità della fragilità. E in questo spazio esposto, la vulnerabilità non è debolezza, ma linguaggio. Non si tratta di mostrare, ma di lasciar emergere — come fa la voce quando trema, quando cerca, quando si espone.

to love and devour non è soltanto un titolo, è un confine sottile dove si appoggiano due gesti opposti, o forse due facce della stessa fame. Amare significa prendersi cura, ma anche farsi strada nell’altro, scavarlo piano. Divorare è portare dentro, far sparire, ma è pure un modo di lasciare che qualcosa entri a dissolverci. Qui, tra queste mura che parlano di acqua e di polvere, il palazzo si lascia amare, perché si lascia ferire. Si lascia divorare dai passi, dagli sguardi, dal cantiere che lo apre e lo spariglia.

Chi attraversa queste stanze finisce per divorare e farsi divorare, senza difese. È così che l’arte somiglia all’amore: resta un rischio, un contatto che ci smargina, che ci frantuma un po’. E forse non c’è modo più vero di abitare un luogo se non questo: cedere alla sua fragilità, lasciarsi invadere dal suo silenzio, consumarlo e farci consumare, fino a confondere la pelle con la parete, la voce con un passaggio a nudo, la memoria con la polvere.

In to love and devour, anche la dimensione del tempo è rizomatica: non lineare, non progressiva, ma stratificata e porosa. Astakhishvili ha abitato il palazzo per mesi, ne ha registrato le oscillazioni di luce, i rumori interni, la respirazione segreta delle stanze. Ha accettato l’incompiuto come forma di sincerità: testimonianza di un processo in atto piuttosto che di un risultato concluso. Il suo è un tempo che si dilata e si contrae come un tessuto organico, consentendo all’esperienza di accadere, per ciascun visitatore, in modo irripetibile.

Persino l’architettura, diventa un rizoma materiale. L’artista ha compiuto ciò che raramente è concesso in una casa storica veneziana: ha inciso, rimosso, aperto. Non per restaurare un’origine, ma per rivelare la natura stratificata e vulnerabile dell’edificio. Le tubature che corrono sulle pareti, i pavimenti segnati da impronte recenti, gli intonaci lasciati a metà non raccontano un abbandono, ma la vita: la casa come organismo poroso, fatto di tempo e di ferite. In questo spazio alterato, l’architettura smette di essere fondo neutro: respira, parla, accoglie. E ogni manipolazione, ogni dettaglio lasciato in sospeso, diventa traccia di un’ospitalità radicale — dove anche l’errore, la rovina, la polvere sono parte della voce del luogo.

Nulla è levigato, nulla risolto. Le superfici slabbrate, i materiali poveri, gli spigoli lasciati vivi sono testimoni di una scelta: quella di autorizzare che sia l’incompiuto a parlare. Ogni tubo scoperto è una confessione, ogni crepa un frammento di storia che riaffiora.

Camminare tra queste stanze è un gesto di intimità e disorientamento. Il visitatore si muove come in un labirinto organico, senza direzione imposta. Ogni ambiente è un nodo di connessione: si intrecciano il palazzo rinascimentale, lo studio di Ettore Tito, l’ambulatorio del Novecento, la comunità artistica odierna. La casa non è più solo contenitore, ma campo di forze, presenza viva. In questo modo il palazzo di Dorsoduro si popola di presenze multiple, ciascuna autonoma e vulnerabile, eppure capace di radicarsi nella stessa trama: una comunità temporanea che fa del luogo un rizoma di voci, di corpi, di memorie che si cercano e si riconoscono, pur restando irriducibilmente diverse. Si abita la crepa, si attraversa l’incompiuto, si sceglie di non dominare il materiale, ma di lasciarlo esistere in tutta la sua precarietà.

In questo rifiuto della perfezione, la vulnerabilità diventa linguaggio, e l’opera si fa soglia. Il rizoma qui non è solo una metafora concettuale, ma una realtà esperienziale: lo si calpesta, lo si sfiora con lo sguardo e con le mani, lo si respira nell’aria carica di polvere e memoria.

Nicoletta Fiorucci Foundation, con il suo programma che intreccia committenza e ospitalità, ha reso questo intervento possibile, offrendosi non solo come spazio espositivo ma come dimora viva, nella linea di una collezione e di una progettualità che ha sempre preferito l’ibrido, la soglia, la contaminazione. Come un rizoma, questa mostra si espande senza un disegno predefinito, si lascia incidere dagli incontri e dalle derive, accoglie deviazioni e differenze. Non offre rassicurazioni, ma ci chiede di sostare nel dubbio, nell’incompiuto, in quel tempo fragile che ci ricorda quanto siano provvisorie le nostre case, i nostri corpi, le nostre identità. Forse per questo, attraversare le stanze di to love and devour è un’esperienza tanto toccante. Non è una mostra quella che prende forma, si entra in una casa che parla, che confida le sue crepe, che si offre come spazio di incontro tra memorie georgiane, tracce veneziane e visioni contemporanee. Una casa che, come scrivono Deleuze e Guattari, “non comincia e non finisce, ma è sempre nel mezzo, tra le cose, intermezzo”. E come ogni rizoma, questo progetto resta aperto: disponibile a future ramificazioni, a nuove intromissioni, a storie che si aggiungeranno alle storie. In un mondo che tende a chiudere, a definire e a classificare, Tolia Astakhishvili ci invita piuttosto a perdere l’orientamento, ad accogliere la complessità, a sostare nel molteplice. E in questo gesto, così intimamente vulnerabile, risiede forse la forma più radicale di amore — e di arte — che ci sia data di sperimentare.

Cover: Tolia Astakhishvili, forbidden place, 2025 room, pipes, boiler, monitor HIM, hand-drawn animation 2 min, loop

Rhizomes of water and dust | | Nicoletta Fiorucci Foundation, Venice

Text by Rita Selvaggio —

Venice is a city that, more than any other, seems made of subtractions and pauses, of what is missing and of what slips away. A place where water is both wall and street, where even time floods and slows into the steady beat of oars. Joseph Brodsky, who chose it as his winter refuge, once wrote that Venice is “a postcard sent from nowhere to nowhere” (Watermark, 1992): a message without sender or recipient, which nonetheless arrives unfailingly at the heart of whoever crosses it. Walking through Dorsoduro, or any other sestiere, one feels something akin to a letter never posted, a discourse cut off mid-sentence. Here the walls seep stories that refuse to be told all at once, letting them fall instead like whispered confidences. Silence is not emptiness but an echo bouncing between narrow calli and sudden courtyards, multiplying across the canals as on a shattered mirror. And perhaps this is the most authentic measure of Venice: not the opulence of façades nor the solemnity of churches, but its fragile substance, the stubborn precariousness that holds it above the water, like the hypothesis of a city always on the verge of dissolution.

In Venice water is not merely backdrop, but an active matter that shapes the city. Every palace rests on piles driven deep into the mud, breathes with the tide, yields to the corrosion of salt. Architecture here is a fragile pact between the weight of stone and the yielding of water, a precarious balance that renews each day the risk of ruin. To inhabit Venice is thus to accept that time and the lagoon are invisible architects, endlessly cutting, chiselling, reshaping.

There is a corner of Venice, among its less clamorous folds yet dense with secrets, that for centuries has sheltered artists’ studios, workshops, and quiet dwellings lapped by canals as narrow as veins of water. The sestiere of Dorsoduro was for centuries the district where merchants unloaded spices and dyed cloths, amid warehouses scented with camphor and quays alive with a babel of dialects. Here painters’ workshops took root, drawing schools were opened, and small presses printed prayer booklets or melodramas. Commercial vitality mingled with a domestic quiet made of washing lines strung across bridges and hidden courtyards. Even today, walking through these calli, one seems to tread a geography of trades, traces of industrious lives that have settled like silt between the foundations.

Dorsoduro — so called because it rose on ground relatively firm compared to the surrounding marshes, a hard ridge — over the centuries welcomed convents, patrician palaces, mercantile docks. Within this urban fabric, dense with overlapping memories, the Nicoletta Fiorucci Foundation has found its home in a fifteenth-century building. Founded to support the most experimental, ecological, feminist, and decolonial forms of contemporary art, the Foundation inaugurated its Venetian base here with the intent of transforming this place into a living platform, permeable and habitable.

A palazzo that bears on itself the stratifications typical of the city: once a noble Renaissance residence, where perhaps the echo of feasts and salons still clings to the high ceilings; later the studio of Ettore Tito, a painter who loved to depict faces and bodies as if they floated in Venice’s heavy air, figures emerging from a dream of salt. Of that passage remain, perhaps, faint shadows on the walls, light impressions that blur into the dust. Later still it became a medical clinic, rooms that witnessed wounded bodies, fevered hands, voices of care or fear, leaving behind an odor of antiseptic mingled with hope. Today it is a space for art that welcomes other fragilities, other attempts to tell what trembles, with works that open passages and questions slipped into the walls. A house that, like so many in Venice, never ceases to transform, altering its identity through the layers of time.

It is in this palazzo of Dorsoduro that Tolia Astakhishvili, a Georgian artist born in Tbilisi in 1974, chose to “inhabit.” To inhabit is not merely to occupy a space, but to allow it to transform us. Heidegger would say that to inhabit is “to safeguard Being,” to care for what exceeds us. Astakhishvili has inhabited in the most radical sense: she let herself be permeated by the rhythm of the rooms, by the dust, by the creaks of the night, allowing the house to enter her as much as she entered the house. The result is an encounter between reciprocal vulnerabilities. For months she lived within these walls, moving like an attentive guest, letting the palazzo speak through its very fissures. She stripped plaster, opened passages, exposed pipes, altered the arrangement of walls and thresholds, inserted mirrors and salvaged materials. She allowed the past and present of the house to entwine in a fragile dialogue, where every room holds uneasy breaths.

It is no surprise that Venice itself, the palimpsest city par excellence, should become the stage for this gesture. Here architecture has always revealed itself as a rhizomatic organism: a network of islands, canals, bridges, mooring poles, branching horizontally without a dominant center. Venetian houses are palimpsests of stone and water, born of continual additions, grafts, elevations, conversions. A perfect model for grasping the nature of this project.

Astakhishvili’s practice always moves in suspension: between construction and ruin, between intimacy and exposure, between the artist’s gesture and the mute response of architecture.

Her intervention in places is never purely aesthetic: it is an act of radical unveiling, of unprotected proximity. Here she strips walls as though peeling skin, letting veins of pipes surface, scars of plaster, memories of water.

Yet at the same time she sutures the place with minimal presences, fragments. As if to say that the house — the space — is never a neutral container, but a body inhabited, vulnerable, mortal. This poetics of precarious dwelling is also reflected in her drawings and paintings, often installed as uncertain presences, camouflaged on the walls or half-hidden, compelling the viewer to an act of search, a perceptual slowing down. They are apparitions that speak of genealogies, of flights and returns, but always allusively: traces rather than narratives, imprints that resist becoming linear account.

to love and devour, the title of this site-specific intervention, is first of all a gesture of relinquishing the traditional idea of a solo exhibition. Curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist, the project takes shape as a discursive and relational device, culminating in the publication of an artist’s book of the same name, issued by Lenz Press, which documents it. It is no minor detail that to love and devour should take form precisely during the Venice Architecture Biennale, almost as a silent counterpoint. If the Biennale investigates architecture as project and structure, Tolia Astakhishvili questions the very idea itself, bringing to light the threshold, the ruin, the fragile. Not a pavilion, but an organism. Not a vision, but an adhesion to place.

The exhibition unfolds as a shifting weave: it imposes no paths, but lets things happen — works, architecture, and memories meeting, disturbing, transforming one another. There is no sequence to follow, no narrative thread to guide: it is the palazzo itself that becomes a porous body, traversed by presences that seem to sprout from its wounds. Astakhishvili has in fact invited other artists into this experiment, not as an addition but as the organic extension of her own gesture: what emerges is not a sum, but a field of shared intensities. A rhizome that propagates through horizontal connections, where identities touch, mingle, blur — where each one adds a branch, a pulse, a deviation that fuses with the secret breath of the rooms.

The works of the involved artists do not interrupt, do not erupt. They enter on tiptoe, like a memory resurfacing when least expected. They do not illustrate, but breathe together with the space: they allow themselves to be touched and transformed, like living matter exposed to the moods of the rooms. Every gesture is a caress that settles — and at the same time dissolves — into the vulnerable body of the palazzo.

Moving through the rooms, Nails (2025) by Ketuta Alexi-Meskhishvili grazes the retina like a childhood reminiscence: a suspended inkjet print on cotton, its contours seeming to liquefy as light passes across the surface, caught for an instant and immediately released. It is a lightness that does not fold in on itself but finds an echo in Taste (Snoring and the Sound of Pigeons), a sculptural installation with an audio piece by Dylan Peirce inside. Dylan’s ambient soundscape is a sonic topography of Venice’s manifold channels that modulate and mediate sound. The piece is built from recordings captured at different levels throughout the city – for example, street life recorded through a large metal shaft, combined with the noise of ventilators and pipes. The whole sculpture becomes a sonic organism, vibrating beyond its physical form. The video From Here to There (Sidewalks) also has a soundscape by Dylan and extends this logic of displacement: a fragmentary montage, marginal details, repeated passages that generate the sensation of a suspended walk, as though the work itself is a journey without destination.

It is within this weave of subtle apparitions that the work of Thea Djordjadze takes shape, as though absence were the natural continuation of an image that resists grasp. In Untitled, 2020, 4 metal objects, each 20.5 × 12 × 12 cm), the small metallic objects nearby act as minimal signs of resistance, fragments of a kind of domestic archaeology.

And again, as if to underscore this logic of precariousness, Zurab Astakhishvili — Tolia’s father — leaves notes that seem to hold back time through collages on windows and an architectural model, (I Can’t Imagine How I Can Die If I’m So Alive, 2025; Suddenly the World Became Loud II, 2024), affective fragments pinned to the vulnerability of matter. The collages are displayed in unstable balance: covering the surfaces on a shoe box turned upside down and a shelf placed without functionality on the floor.

Just as Zurab’s notes remain suspended between project and ruin, so too does Heike Gallmeier work along a fragile threshold: in Prospective Dream (2010, analogue C-print on Alu-Dibond, framed, 170 × 220 cm), photography becomes both passage and fragment. The composition unfolds as a reconstructed, photographed three-dimensional collage: fragments of architecture, improvised still life, stage-like backdrops that seem to waver between image and reality. The shot thus becomes both document and illusion. Upon this unstable ground rests the work of Rafik Greiss, the right to rest and leisure I, II (C-prints on Japanese paper, collage, 50 × 60 cm; 60 × 75 cm). In his work bodies and photographic fragments, assembled on delicate, almost translucent sheets, seem to rise and fade, held in suspension between apparition and erasure.

James Richards and Tolia’s collaborative work Our Friends in the Audience (2024, print, marouflage on canvas, 200 × 130 cm) is a whispered print, an absorptive surface closer to an inscribed shadow than to a finished image, while I Remember (Depth of Flattened Cruelty) 2023, a HD video, 10:16 min, created with Tolia Astakhishvili, breathes with the walls, projecting rarefied images that seem to dissolve into the very materials of the room, merging with its coverings. The work of Maka Sanadze seems to gather precisely what lingers from these passages: ephemeral signs, intimate fragments, traces of a language that escapes. Her works (Untitled, treated magazine pages, 38 × 29 cm; 46 × 36.5 cm) emerge as worn, stained surfaces, halfway between relic and debris — torn pages bearing the imprint of time, inscriptions that survive only in fragments.

This same principle of precariousness inhabits the palazzo in other interventions, which appear as organic modifications rather than isolated works: a bathroom reduced to a skeletal structure (My Emptiness, 2025, sectioned walls, excavated pipes, bathtub), resembling a stripped-down body where the pipes intertwine like exposed bones; an architectural model hidden in a service space (House of Mending, 2024–2025, cardboard, papier mâché, glasses, stickers, duvet, toilet, box with dust, glass), scattered with humble materials and remnants; a drywall partition leaning against a bare wall (When the Others Are Within Us, 2025, drywall, plaster, coffee, ink, artificial snow, 980 × 266 cm), revealing itself as a temporary barrier; framed drawings in plexiglass (A Timeline with Physical Attributes, 2025, paper, pencil, ink, pastel, 31 × 22 cm each), laid out almost like ex-votos or provisional maps

The concept of the rhizome, as imagined by Deleuze and Guattari, becomes here both curatorial method and form of experience: a system that refuses hierarchies, central structures, univocal signatures. There is no One that divides, nor a Multiple that returns to an origin. There is a plural that shifts dimension, expands in a non-linear way, grows by grafts, by detours, by contaminations. Thus, authorial subjectivity dissolves as well: there is no single voice to guide, but a chorus generated through friction, through listening, through exposure.

There is a voice that exposes itself without shield, as Adriana Cavarero describes it: fragile, unrepeatable, incarnate. A voice that does not precede the body but translates it into sound, rendering audible its vulnerable uniqueness. And there is a writing that trembles on the margin, like that of Anne Carson: a voice that does not defend itself, that vibrates in the fissure and, precisely for this, is able to touch. The stripped-down rooms of Astakhishvili — with exposed pipes, peeled walls, objects like remnants — are like the mute vocal cords of the building: they do not speak, but whisper from beneath the skin. To show these wounds is not a gesture of self-indulgence, but a stance: a political act opposing smoothness, performance, closure. Here, in the crack, in suspension, the truth of fragility is recognized. And in this exposed space, vulnerability is not weakness, but language. It is not a matter of showing, but of letting emerge — as the voice does when it trembles, when it seeks, when it exposes itself.

to love and devour is not merely a title, but a fine boundary where two opposite gestures rest, or perhaps two faces of the same hunger. To love means to care, but also to carve a way into the other, to hollow it gently. To devour is to draw inside, to make disappear, but it is also a way of allowing something to enter and dissolve us. Here, among these walls that speak of water and of dust, the palazzo allows itself to be loved because it allows itself to be wounded. It allows itself to be devoured by footsteps, by gazes, by the chantier that opens and unsettles it.

Whoever crosses these rooms ends by devouring and being devoured, unguarded. This is how art resembles love: it remains a risk, a contact that unsettles us, that fractures us a little. And perhaps there is no truer way of inhabiting a place than this: to yield to its fragility, to let oneself be invaded by its silence, to consume it and be consumed by it, until skin is confused with wall, voice with a passage laid bare, memory with dust.

Even the dimension of time, in to love and devour, is rhizomatic: not linear, not progressive, but layered and porous. Astakhishvili inhabited the palazzo for months, registering its oscillations of light, its inner noises, the secret respiration of the rooms. She accepted incompletion as a form of sincerity: testimony of a process in motion rather than a finished result. Hers is a time that dilates and contracts like an organic fabric, allowing the experience to occur in a way that is unrepeatable for each visitor.

Even architecture itself, in Astakhishvili’s exhibition, becomes a material rhizome. The artist has done what is rarely permitted in a historic Venetian house: she has cut, removed, opened. Not to restore an origin, but to reveal the stratified and vulnerable nature of the building. The pipes running along the walls, the floors marked by recent imprints, the half-finished plasterwork do not speak of abandonment, but of life: the house as a porous organism, made of time and wounds. In this altered space, architecture ceases to be a neutral backdrop: it breathes, speaks, welcomes. And every manipulation, every detail left unfinished, becomes the trace of a radical hospitality — where even error, ruin, dust are part of the voice of the place. Here nothing is smoothed over, nothing resolved. The ragged surfaces, the poor materials, the edges left raw all bear witness to a choice: that of letting incompletion speak. Every exposed pipe is a confession, every crack a fragment of history resurfacing.

Walking through these rooms is a gesture of intimacy and disorientation. The visitor moves as in an organic labyrinth, without an imposed direction. Every space is a knot of connection: the Renaissance palazzo, Ettore Tito’s studio, the twentieth-century clinic, the contemporary artistic community all intertwine. The house is no longer merely a container, but a field of forces, a living presence. In this way the palazzo of Dorsoduro fills with multiple presences, each autonomous and vulnerable, yet able to root itself in the same weave: a temporary community that turns the place into a rhizome of voices, of bodies, of memories that seek one another and recognize one another, while remaining irreducibly diverse.

Here one inhabits the crack, traverses incompletion, chooses not to dominate the material but to let it exist in all its precariousness. In this refusal of perfection, vulnerability becomes language, and the work becomes threshold. The rhizome here is not only a conceptual metaphor but an experiential reality: it is trodden underfoot, brushed by the gaze and the hands, breathed in with the air thick with dust and memory.

The Nicoletta Fiorucci Foundation, with its program interweaving commissioning and hospitality, has made this intervention possible, offering itself not only as an exhibition space but as a living dwelling, in the spirit of a collection and a vision that has always privileged hybridity, thresholds, contamination. Like a rhizome, this exhibition expands without a predetermined design, allowing itself to be marked by encounters and by drift, welcoming deviations and differences. It offers no reassurance, but asks us instead to pause in doubt, in incompletion, in that fragile time which reminds us how provisional our homes, our bodies, our identities truly are.

Perhaps for this reason, to walk through the rooms of to love and devour is such a moving experience. What takes shape is not an exhibition, but a house that speaks, that confides its cracks, that offers itself as a place of encounter between Georgian memories, Venetian traces, and contemporary visions. A house which, as Deleuze and Guattari write, “does not begin and does not end, but is always in the middle, between things, intermezzo.” And like every rhizome, this project remains open: available to future ramifications, to new intrusions, to stories that will add themselves to other stories.

In a world that tends to close, to define, to classify, Tolia Astakhishvili invites us rather to lose our bearings, to welcome complexity, to dwell in the multiple. And in this gesture — so intimately vulnerable — perhaps lies the most radical form of love, and of art, that we are given to experience.

Cover: Tolia Astakhishvili, forbidden place, 2025 room, pipes, boiler, monitor HIM, hand-drawn animation 2 min, loop