English text below

Testo di Luciana Fabbri —

Si chiama Pepsis la mostra di Roberto Cuoghi inaugurata da Hauser and Wirth a New York il 26 gennaio e visitabile fino al 1° aprile. Artista misterioso, ironico ed evocativo Cuoghi ha rappresentato l’Italia insieme agli artisti Giorgio Andreotta Calò e Adelita Husny Bey alla Biennale di Venezia del 2017 curata da Cecilia Alemani. La mostra è la prima dell’artista in galleria, e la prima a New York dopo circa dieci anni.

Entrati in mostra, la prima cosa che risalta all’occhio è un tappeto a forma di ragno fatto di seta, lana, e acrilico e che mostra la mappa del mondo di notte. Uno scenario notturno immaginario che coinvolge, nello stesso momento, tutte le nazioni del mondo. Al centro dell’opera, vediamo gli Stati Uniti d’America.

Nonostante il richiamo apparentemente pop, Pepsis è una parola che in greco vuol dire digestione, ma è anche il nome scientifico di una vespa ragno che si attacca ad un altro insetto per nutrire i suoi piccoli, manipolando il suo comportamento fino alla sua morte, mentre le larve Pepsis lo divorano dall’interno. Osservando questo fenomeno Charles Darwin scrisse di aver perso la fiducia nella benevolenza divina in cui era stato portato a credere.

Il titolo dell’opera è A(XLVIIPs)t. XLVII è un numero romano che corrisponde al 47. Tenendo conto che di fronte troviamo la torta presidenziale di Donald Trump, 45esimo presidente americano, il titolo potrebbe suggerire il monito di un futuro che potrebbe ritornare, in una maniera spaventosa.

Di fronte al tappeto, troviamo due torte, che sono le repliche della torta presidenziale di Donald Trump e della torta nuziale di John Kennedy Jr. e Caroline Besset. L’artista ci ricorda di un dettaglio ridicolo quanto significativo, ovvero che Trump volle la sua torta quattro volte più grande di quella dei suoi predecessori. Le torte sono fatte di meringa, pasta di zucchero, fiori conservati, resina e polistirolo e sprigionano un odore dolciastro.

Un’altra opera presente in questa sala è P+SS(IVP)po/c, composta da un dipinto, raffigurante due signore anziane a braccetto, e da due sculture in ceramica poste di fronte. Il colore nero dei cappottini delle signore in lana e cachemire è predominante. L’artista è noto per avere un’attenzione quasi ossessiva ai dettagli nella composizione delle sue opere. Le signore hanno le mani in tasca, tranne quella delle donne a destra, che spunta mentre prende il braccio della vicina. Questa mano bianca inquietante, che si staglia nel buio in posizione molle, porta un anello al dito medio, che sembra sottolineare la sua posizione al centro tra le due figure. Pochi sono i dettagli sulla collocazione della scena, e accennano a un paesaggio naturale sull’acqua sul lato sinistro e ad uno più vago, con dei ciottoli, a destra.

Le due sculture di ceramica di fronte alla tela raffigurano due blocchi di fogli, su cui in cima leggiamo l’incipit del romanzo storico di Charles Dickens A tale of Two Cities (1859). L’incipit è famoso perché contiene frasi contraddittorie, con l’intento di creare un ponte tra il presente, quello vissuto da Dickens che potrebbe anche essere però il nostro, e il passato, della Rivoluzione Francese. Ma anche un ponte tra classi sociali diverse, tra borghesia e aristocrazia.

«Erano i giorni migliori, erano i giorni peggiori, era un’epoca di saggezza, era un’epoca di follia, era tempo di fede, era tempo di incredulità, era una stagione di luce, era una stagione buia, era la primavera della speranza, era l’inverno della disperazione, ogni futuro era di fronte a noi, e futuro non avevamo, diretti verso il paradiso, eravamo incamminati nella direzione opposta. A farla breve, era quello un tempo così simile al nostro che alcune fra le voci più autorevoli, quelle che più strillavano, insistevano a giudicarlo, nel bene e nel male, solamente per superlativi».

La mostra riflette sulla cultura del consumo americana e occidentale e sul modo in cui siamo abituati a organizzare i nostri pensieri e il mondo. Un consumo di tipo estrattivo, come si potrebbe dedurre dalla scelta dei vestiti delle signore in materiali preziosi. Cuoghi scinde l’incipit del romanzo in due tempi distinti e sembra ammonirci riguardo alla possibilità della ripetizione del passato, dei suoi errori e dei suoi estremismi.

Nella scelta dei colori bianco e nero per quest’opera, ma anche dalla decisione di esporre la mappa del mondo di notte, l’artista fa emergere una tensione tra luce e buio. Già nel 2019 con l’installazione M I R A C O L A, Cuoghi aveva scelto di spegnere le luci di piazza San Carlo a Torino, per pochi secondi, ogni ora dopo le nove di sera, lasciando tutti al buio. L’intenzione dell’artista era “costringere a considerare i vincoli cognitivi che separano la luce dal buio”.

Spegnere la luce in una città ti può portare a quella paura ancestrale che provavano le persone nei confronti della natura prima di avere la luce artificiale. Allo stesso tempo, l’improvvisa esperienza del buio può costituire una rivelazione in quanto, cogliendoci impreparati, ci spinge a riconsiderare i modi in cui abbiamo pensato e agito fino a quel momento.

C’è una riflessione storico filosofica che lega il lavoro di Cuoghi a un discorso sull’Illuminismo. Horkeimer e Adorno nel La dialettica dell’Illuminismo (1947) rileggono la storia della civiltà occidentale dimostrando come sia legata totalmente al pensiero illuminista. La narrazione positiva dell’illuminismo racconta dell’emancipazione dell’uomo dalla natura e del progressivo controllo che egli impone su di essa ma i due filosofi rivelano il lato oscuro di questa storia mostrando l’illusorietà del dominio umano e la potenza vendicatrice della natura. I due filosofi parlano di asservimento della ragione alla sua funzione di strumento. La ragione è diventata strumento, non più per comprendere in maniera etica, morale o religiosa la nostra esperienza nel mondo, quanto piuttosto in relazione alla sua capacità di dominare la natura e gli altri uomini. Non a caso il titolo della mostra prende il nome da un parassita.

Si legge nel comunicato stampa: ‘Cuoghi parla di ‘stilizzazione’ come l’antica forza primordiale dell’imparare imitando, permettendo alla conoscenza e alle abilità di essere tramandate, evitando l’errore. È meglio ri-creare che creare qualcosa che potrebbe non essere di successo. Stilizzare significa semplificare e illuminare, che a sua volta vuol dire impoverire allo scopo di conservare e comunicare qualcosa che diviene un modello di riferimento. Secondo Cuoghi, la nuova disponibilità illimitata di modelli da seguire e aspirazioni che modellano e orientano la nostra crescita, sviluppo e socializzazione, ci condanna a digerire e ripetere formule inautentiche. Nessuno è escluso da questo numero sempre crescente di riferimenti che annebbiano la nostra immaginazione, non solo ad un livello estetico, ma anche minacciando la vera idea di innovazione alla radice. In Pepsis Cuoghi interroga questa ipotesi e le sue conseguenze, che in ultima istanza sostituiscono la vera idea di soluzione con delle forme di soluzione stilizzata.’

Scrive l’artista: “Si tratta dell’offerta di informazione che non è più proporzionata alle nostre capacità cognitive, che sono sempre le stesse. Ma stiamo imparando a vivere in overdose”.

Spegnendo il lume, della ragione, Cuoghi denuncia quello che viene comunemente chiamato ragione, portandoci a interrogare il regime del quotidiano normalizzato da regole prestabilite e date per assodate.

Parlando di immagini e modelli di riferimento, nella seconda sala della galleria troviamo altre quattro torte: si tratta delle torte nuziali di Grace Kelly e Ranieri di Monaco, del principe Carlo e Diana Spencer, di John Kennedy e Jacqueline Bouvier, e la torta presidenziale di Obama (anche se dal titolo XLII, che è 42 in numeri romani, potrebbe anche essere quella di Bill Clinton). Promesse di felicità finite in tragedia. Alcune torte hanno addirittura una base lignea, che ricorda una bara. Questi simboli celebrativi sono posti in netto contrasto con un’immagine di un altro tipo di consumo, da Starbucks.

Nel dipinto intitolato P(XLIXPs)po vediamo un gruppo di persone sedute di fronte a Starbucks. Non sappiamo nient’altro sull’ambientazione. Forse un parcheggio, o un luogo d’attesa. Agli antipodi del clima festoso e promettente dei dolci, troviamo un’immagine anti-celebrativa di un gruppo di persone, una in posizione gobba, un’altra su una sedia a rotelle, un’altra il cui volto si fonde con il logo del brand. È interessante notare che il logo di Starbucks ritrae il volto di una sirena. In molte lingue, una sirena è suono che avvisa un’emergenza in corso. Nella mitologia greca le sirene erano figure ambivalenti dalla voce seducente, irresistibili e letali. Il loro canto attirava i marinai, che si gettavano in mare per raggiungerli, finendo per annegare. Nel poema omerico dell’Odissea, Odisseo decise di tappare le orecchie dei suoi compagni con la cera durante la traversata e si fece legare all’albero maestro per poter ascoltare il loro canto, evitando però di cadere nella loro insidiosa trappola.

Sembra che la mostra di Cuoghi, con il suo eccesso di zuccheri, informazioni e rifiuti si rifletta bene con l’opera di Georges Bataille La Parte Maledetta (1949) dove l’autore affronta il paradosso dell’eccedenza: al massimo dell’esuberanza produttiva corrisponde il massimo della perdita. L’attività umana moderna si fonda sul dispendio di energie e merci, sino al dispendio – fine a se stesso – di vite umane.

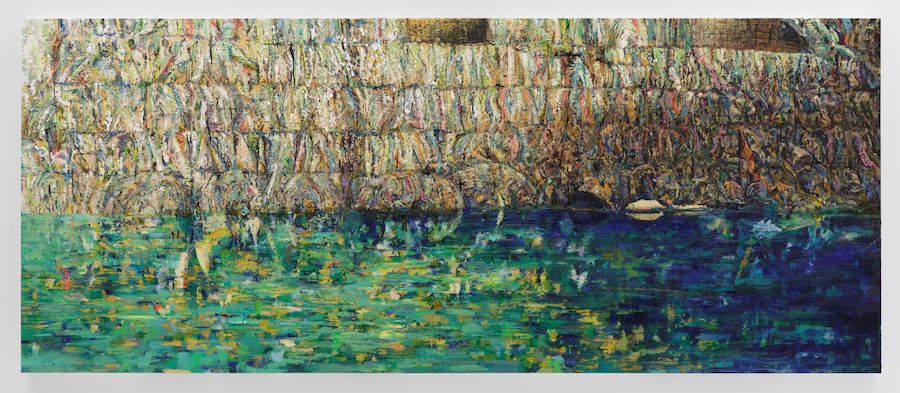

Su un lato della parete della galleria vediamo più ritratti, per lo più di persone anziane, che l’artista ha preso dal TIME Magazine durante il picco della pandemia. Disposti come un ironico wall-of-fame, i ritratti sono fluidi, in evoluzione. L’artista mette in risalto la loro individualità. Le loro emozioni non sono di facile identificazione. Sul lato opposto della stanza, vediamo un grande dipinto, che a prima vista ricorda le famose ninfee di Monet, ma questa volta invece dello scenario idilliaco, vediamo cumuli di rifiuti accatastati, pronti per essere eliminati. La pittura stratificata sembra riflettere l’ammassamento dei rifiuti. Le persone, situate in maniera speculare rispetto ai rifiuti, diventano una lo specchio dell’altra, prodotti soggetti a consumo e smaltimento.

In queste circostanze, alcune persone potrebbero rivolgersi alle voci, come delle sirene, dei leader demagoghi che forniscono risposte facili e false promesse. Ma c’è anche la possibilità che l’esperienza della pandemia, possa portare a nuove forme di coscienza e nuovi modi di pensare e condurre le nostre vite. Potrebbe anche portare a nuove forme di leadership che promuovano la responsabilità civica e la solidarietà tra le nazioni, spazzando via coloro che hanno lavorato per alzare muri tra queste. Come dice l’artista: “Anche in un circuito chiuso c’è sempre un po’ di prospettiva davanti a te”.

The excess of reason – Roberto Cuoghi | Hauser and Wirth, New York

Pepsis is the name of the Roberto Cuoghi exhibition inaugurated by Hauser and Wirth in New York on 26 January and open until 1 April. Mysterious, ironic and evocative artist Cuoghi represented Italy along with the artists Giorgio Andreotta Calò and Adelita Husny Bey at the 2017 Venice Biennale curated by Cecilia Alemani. The exhibition is the artist’s first in the gallery, and the first in New York after about ten years.

As you walk in the gallery, the first thing that catches your eye is a spider-shaped tapestry made of silk, wool, and acrylic, which shows the world map at night. An imaginary nocturnal scenario that involves all the nations of the world at the same time. At the center of the work, we see the United States of America.

Despite the apparently pop appeal, Pepsis is a Greek word for digestion, but it is also the scientific name of a spider wasp that attaches itself to another insect to feed its young, manipulating its behavior until it dies, while Pepsis larvae devour it from the inside. Observing this phenomenon Charles Darwin wrote that he lost faith in the divine benevolence in which he had been led to believe.

The title of the work is A(XLVIIPs)t. XLVII is a Roman number which corresponds to 47. Taking into account that in front of us we find the presidential cake of Donald Trump, the 45th American president, the title could suggest the warning of a future that could return, in a frightening way.

In front of the tapestry, we find two cakes, which are replicas of Donald Trump’s presidential cake and John Kennedy Jr. and Caroline Besset’s wedding cake. The artist reminds us of a detail as ridiculous as it is significant, which is that Trump wanted his cake four times bigger than that of his predecessors. The cakes are made of meringue, sugar paste, preserved flowers, resin and polystyrene and give off a sweet smell.

Another work in this room is P+SS(IVP)po/c, consisting of a painting, depicting two elderly ladies arm in arm, and two ceramic sculptures placed in front of the painting. The black color of the ladies’ wool and cashmere coats is predominant. The artist is known for having an almost obsessive attention to detail in the composition of his works. The ladies have their hands in their pockets, except that of the women on the right, which sticks out as she takes the arm of her neighbor. This disturbing limp, white hand wears a ring on the middle finger, which seems to remark its position in the center between the two figures. There are few details on the location of the scene, and they hint at a natural landscape on the water on the left side and a vaguer one, with pebbles, on the right.

The two ceramic sculptures in front of the canvas depict two blocks of paper, on top of which we read the incipit of Charles Dickens’ historical novel A Tale of Two Cities (1859). The incipit is famous because it contains contradictory sentences, with the intention of creating a bridge between the present, the one experienced by Dickens which could also be ours, and the past of the French Revolution. But also, a bridge between different social classes, between the bourgeoisie and the aristocracy.

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of light, it was the season of darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to heaven, we were all going direct the other way–in short, the period was so far like the present period, that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on its being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only.”

The exhibition reflects on American and Western consumer culture and on the way we are used to organizing our thoughts and the world. A consumption of an extractive type, as could be deduced from the choice of the ladies’ clothes in precious materials. Cuoghi splits the incipit of the novel into two distinct moments and seems to warn us about the possibility of repeating the past, its errors and its extremes.

In the choice of black and white colors for this work, but also in the decision to display the world map at night, the artist brings out a tension between light and dark. Already in 2019 with the installation M I R A C O L A, Cuoghi had chosen to turn off the lights of Piazza San Carlo in Turin, for a few seconds, every hour after nine in the evening, leaving everyone in the dark. The artist’s intention was “to force one to consider the cognitive constraints that separate light from dark”.

Turning off the lights in a city can lead you to that ancestral fear that people felt towards nature before having artificial light. At the same time, the sudden experience of darkness can be a revelation as, by catching us unprepared, it pushes us to reconsider the ways we have thought and acted up until that moment.

There is a historical-philosophical reflection that links Cuoghi’s work to a discourse on the Enlightenment. Horkeimer and Adorno in The Dialectic of Enlightenment (1947) reread the history of Western civilization demonstrating how it is totally linked to Enlightenment thought. The positive narrative of the Enlightenment tells of man’s emancipation from nature and the progressive control he imposes on it but the two philosophers reveal the dark side of this story by showing the illusoriness of human domination and the avenging power of nature. The two philosophers speak of the enslavement of reason to its function as an instrument. Reason has become an instrument, no longer to understand our experience in the world in an ethical, moral or religious way, but rather in relation to its ability to dominate nature and other men. It is no coincidence that the title of the exhibition takes its name from a parasite.

The press release reads: ‘Cuoghi speaks of ‘stylization’ as the ancient primordial force of learning by imitating, allowing knowledge and skills to be handed down, avoiding mistakes. It’s better to re-create than to create something that may not be successful. Stylizing means simplifying and illuminating, which in turn means impoverishing in order to preserve and communicate something that becomes a reference model. According to Cuoghi, the new unlimited availability of models to follow and aspirations that shape and direct our growth, development and socialization condemns us to digest and repeat inauthentic formulas. No one is excluded from this ever-increasing number of references that cloud our imagination, not only at an aesthetic level, but also threatening the very idea of innovation at its root. In Pepsis Cuoghi questions this hypothesis and its consequences, which ultimately replace the real idea of a solution with stylized forms of solution.’

The artist writes: “It is about the offer of information that is no longer proportionate to our cognitive abilities, which are always the same. But we are learning to live with an overdose”.

By turning off the light of reason, Cuoghi denounces what is commonly called reason, leading us to question the regime of the everyday normalized by pre-established and taken for granted rules.

Speaking of reference images and models, in the second room of the gallery we find four other cakes: the wedding cakes of Grace Kelly and Ranieri of Monaco, Prince Charles and Diana Spencer, John Kennedy and Jacqueline Bouvier, and the presidential cake of Obama (although titled XLII, which is 42 in Roman numerals, could also be that of Bill Clinton). Promises of happiness ended in tragedy. Some cakes even have a wooden base, resembling a coffin. These celebratory symbols are placed in stark contrast to an image of another type of consumption, at Starbucks.

In the painting titled P(XLIXPs)po we see a group of people sitting in front of Starbucks. We don’t know anything else about the setting. Maybe a parking lot, or a waiting place. At the antipodes of the festive and promising atmosphere of the cakes, we find an anti-celebratory image of a group of people, one in a hunchbacked position, another in a wheelchair, another whose face merges with the brand logo . Interestingly, the Starbucks logo portrays the face of a mermaid. In many languages, a siren is a sound that alerts you to an emergency. In Greek mythology, sirens were ambivalent figures with seductive voices, irresistible and lethal. Their song attracted sailors, who threw themselves overboard to reach them, ending up drowning. In the Homeric poem of the Odyssey, Odysseus decided to plug the ears of his companions with wax during the crossing and had himself tied to the mainmast in order to hear their song, avoiding however falling into their insidious trap.

It seems that Cuoghi’s work, with excessive sugar, information and food scraps is reflected well in Georges Bataille’s work The Accursed Share (1949) where the philosopher tackles the paradox of surplus: the maximum of productive exuberance corresponds to the maximum of the loss. Modern human activity is based on the expenditure of energy and goods, up to the expenditure – an end in itself – of human lives.

On one side of the gallery wall we see more portraits, mostly of older people, that the artist took from TIME Magazine during the peak of the pandemic. Arranged like an ironic wall-of-fame, the portraits are fluid, evolving. The artist highlights their individuality. Their emotions are not easy to identify. On the opposite side of the room, we see a large painting, which at first glance resembles Monet’s famous water lilies, but this time instead of the idyllic scenery, we see piles of rubbish piled up, ready to be disposed of. The layered application of paint seems to suggest the excessive accumulation of waste. People, placed in a specular way with respect to waste, become mirrors of each other, products subject to consumption and disposal.

In these circumstances, some people may turn to the siren-like voices of demagogue leaders who provide easy answers and false promises. But there is also the possibility that the experience of the pandemic could lead to new forms of consciousness and new ways of thinking and leading our lives. It could also lead to new forms of leadership that promote civic responsibility and solidarity among nations, wiping out those who have worked to put up walls between them. As the artist says: “Even in a closed circuit there is always a little perspective in front of you”.