English text below —

Nella Switch House della Tate Modern, fra le sale dedicate a Nigerian Modernism, la luce non cade: risale, come un respiro trattenuto dal suolo. È una luce che attraversa le opere come una memoria terrestre, un bagliore che si espande dal cuore della materia. Curata da Osei Bonsu con Bilal Akkouche, la mostra è più di un’esposizione: un laboratorio di storia, una riflessione sulla possibilità di costruire una nazione attraverso le proprie immagini.

“Celebrating the originality of Nigerian art in all its power and vitality,” scrive Bonsu nel catalogo, ricordandoci che la modernità africana non è prestito né traduzione, ma invenzione — una fioritura autonoma nata dall’incontro tra tecniche europee e memoria indigena, dal desiderio di ridefinire il visibile a partire dal suolo. Nata da una ricerca pluriennale condotta durante la pandemia nei fondi africani delle università di Birmingham, York e Chichester, l’esposizione affronta una questione cruciale: come restituire all’arte nigeriana la propria modernità negata, sottraendola a categorie etnografiche che per decenni l’hanno imprigionata. La critica britannica, da The Guardian in poi, ha sottolineato quanto questa esposizione sia ambiziosa e contraddittoria: troppo ampia per essere contenuta in un solo sguardo, ma proprio per questo necessaria. Il suo fascino nasce dall’irrisolutezza, dal tentativo di leggere un secolo di storia attraverso opere che non si lasciano disciplinare.

Il percorso si apre con Aina Onabolu, colui che per primo intuì che la padronanza delle tecniche occidentali poteva trasformarsi in un gesto politico. Nel suo realismo disciplinato, appreso tra Lagos, Londra e Parigi, non c’è obbedienza al canone ma desiderio di rovesciarlo dall’interno, di piegare la regola al proprio respiro. Nei ritratti di inizio Novecento — uomini e donne dell’élite lagosiana, avvocati, insegnanti, figure della borghesia nascente — Onabolu traduce la posa accademica in una lingua di orgoglio e di emancipazione. Ogni volto, immerso in una luce severa e precisa, sembra restituire al soggetto africano la possibilità di guardarsi finalmente da sé. Nel suo A Short Discourse of Art (1925) scrive che il realismo è un “linguaggio di libertà”: e in quella formula asciutta si riconosce il suo intero cammino. Padroneggiare la forma occidentale per riscriverla, farla respirare dentro un’altra memoria, significa affermare che la modernità non appartiene a nessuno, che può germogliare ovunque la mano trovi un volto da ricomporre. Nella sua pittura, la tecnica diventa coscienza, la superficie si apre come un varco: l’immagine non rappresenta, genera. Così, scegliendo deliberatamente la tradizione pittorica europea invece delle consuetudini scultoree yoruba, Onabolu non rinnega la propria origine — la trasforma in humus, in terreno fertile per un’altra visione del sé. Akinola Lasekan, suo allievo e successore, raccoglie quella eredità e la porta oltre. Nei suoi dipinti degli anni Quaranta e Cinquanta — Ajaka of Owo, Ogedengbe of Ilesha, le danze rituali e le scene di corte — il corpo africano non è più oggetto di rappresentazione ma figura mitica, presenza che parla il linguaggio dell’epopea. Lasekan fa della pittura una narrazione che intreccia documento e leggenda, cronaca e mito, fino a dissolvere i confini tra storia e visione. Nelle illustrazioni per il West African Pilot di Nnamdi Azikiwe, la satira si fa arma e il ritratto diventa resistenza: una cronaca civile che smaschera il potere e alimenta la coscienza dell’indipendenza. Attorno al suo studio di Lagos, aperto con lo scultore Justus D. Akeredolu, prende forma una piccola repubblica dell’immagine: un luogo dove la tradizione yoruba incontra la modernità urbana, dove il colore diventa testimonianza. Re, guerrieri, madri, antenati: le loro figure restituiscono alla Nigeria la fierezza del proprio volto. In queste tele la materia pittorica è canto e invocazione, un’alleanza di pigmento e memoria in cui la storia si fonde al mito per riaffermare il diritto di esistere. Nello stesso orizzonte si muovono Lamidi Olonade Fakeye, che fonde l’iconografia cristiana con la scultura yoruba, e Olowe of Ise, la cui porta intagliata — esposta a Wembley nel 1924 — ribalta la gerarchia dello sguardo coloniale: il funzionario britannico non domina più la scena, ma la supplica. In quei legni raffinati, incisi con l’adze tradizionale e con strumenti moderni, si compie un passaggio simbolico: la scultura come scrittura di resistenza, la tradizione come avanguardia.

Da questa trama di voci — Onabolu, Lasekan, Fakeye, Olowe — nasce una genealogia della libertà, un modernismo che respira dal suolo e non dall’aria. La modernità, per loro, non è conquista esterna ma spazio interiore: il punto in cui la tecnica europea si piega alla memoria africana e la storia coloniale diventa materia viva, plasmabile. È da questa terra fertile, contraddittoria e luminosa, che si leverà la generazione successiva: quella di Ben Enwonwu, pronto a far vibrare la modernità africana tra la danza e il mito, tra la maschera e la regina.

Accanto a loro, le fotografie di Jonathan Adagogo Green documentano la complessità di un tempo di transizione. Ritraggono l’Oba of Benin dopo la devastazione del 1897: il sovrano deposto, incatenato, a bordo di uno yacht britannico. Green, fotografo al servizio dell’amministrazione coloniale, registra senza volerlo la frattura morale di un impero e la dignità ferita di un regno. Le sue immagini oscillano tra denuncia e compromesso, come se il moderno nascesse già contaminato.

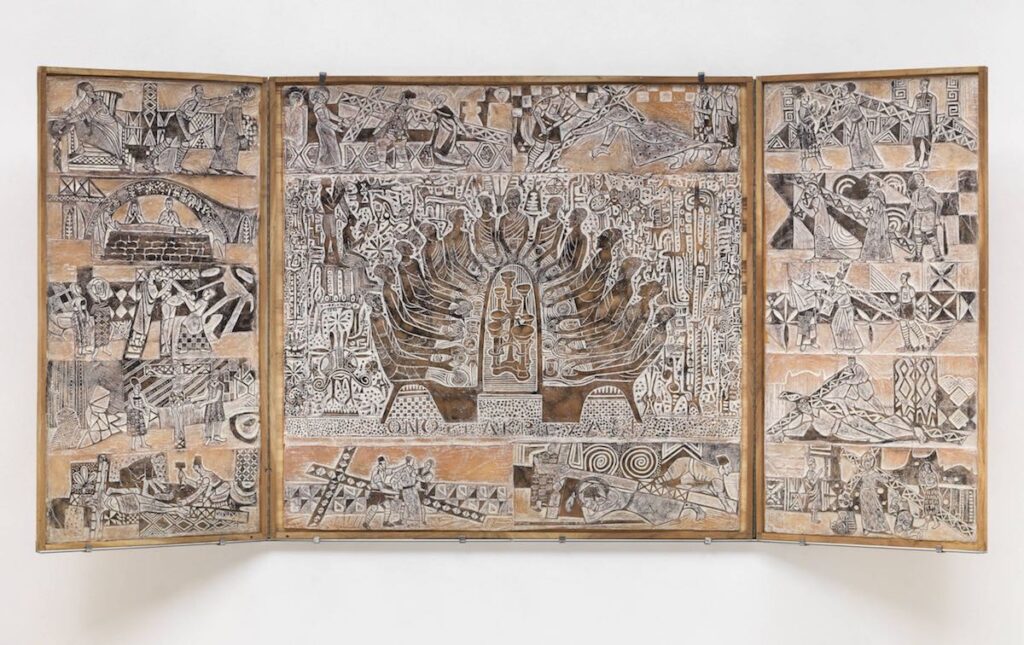

Un pannello scolpito da Olowe of Ise raffigura l’incontro tra l’Ogoga di Ikere e il capitano Ambrose: il colonizzatore, questa volta, appare come supplice davanti al re. È un gesto di sovversione che usa la scultura tradizionale per politicizzare la rappresentazione del potere. Non a caso la mostra evita i bronzi saccheggiati: sceglie piuttosto di ripartire da dove quel racconto si è interrotto, dai gesti di chi ha tentato di ricucire forme e tecniche a un nuovo orizzonte. Il passo successivo porta a Ben Enwonwu, artista simbolo delle contraddizioni tra orgoglio nazionale e appartenenza imperiale. La sua Negritude, metaforicamente e visivamente immagine guida della mostra, traduce la danza in pittura: corpi che si moltiplicano come onde, pigmenti che diventano ritmo. Ispirato alle serate del Caban Bamboo Club di Lagos, Enwonwu cerca di dipingere il suono stesso del movimento. Eppure la sua figura resta ambigua: nel 1956 realizza il ritratto di Elisabetta II, incarnando l’arrivo di una Nigeria indipendente e insieme i valori del Commonwealth. La sua arte attraversa il confine fra mito e potere, fra libertà e deferenza.

Da qui prende forma la tensione che percorre l’intera esposizione: la modernità come equilibrio instabile, mai pacificato.

A differenza di Enwonwu, i giovani della Zaria Art Society – fondatori della Natural Synthesis – rifiutano ogni linguaggio imposto e tentano di decolonizzare la visione. Nel 1958 si riuniscono per reinventare la didattica artistica in Nigeria: la loro rivoluzione è silenziosa e radicale, un modo di pensare la libertà come processo in divenire. Come scrive il curatore, “gli artisti di questa generazione seppero attingere al potenziale emancipatorio della tradizione e della modernità per forgiare un linguaggio nuovo, radicato nell’unità panafricana.” In loro, la memoria non è nostalgia ma forza generatrice: il mito diventa gesto politico, il simbolo si fa lingua dell’indipendenza. La pittura non rappresenta, agisce: un processo in cui la forma è già liberazione. Nelle opere di Uche Okeke e Demas Nwoko la pittura diventa spazio di resistenza: anfibi, soldati, danzatori smascherati popolano un mondo vibrante d’urgenza, come se la tela potesse contenere l’ansia di un paese in trasformazione.

In questa costellazione di tensioni si inserisce Uzo Egonu, pittore di Onitsha trasferitosi giovanissimo a Londra. Le sue tele – Cityscape, Stateless People, Village with Church – sembrano viste attraverso una lente che curva lo spazio: autobus che attraversano Piccadilly, figure isolate, un’inquietudine geometrica che non appartiene né a Lagos né a Londra. L’artista rappresenta l’altro volto della modernità: la diaspora come condizione permanente. Più che cercare una sintesi, il suo linguaggio abbraccia la coesistenza, lascia che le differenze restino in tensione, come nella memoria di chi vive altrove. In Egonu la modernità assume la forma di un esilio interiore: linee spezzate, architetture che vacillano, figure senza radici. Nel ciclo Stateless People (1976–1980 circa), affronta il tema dello sradicamento come condizione universale, non solo politica ma ontologica. Le figure appaiono sospese in spazi frammentati, né terra né cielo, come se la pittura stessa cercasse un luogo dove appartenere. I contorni geometrici che definiscono i corpi si dissolvono in una cartografia emotiva della diaspora: non un paesaggio di perdita, ma una topografia della sopravvivenza. In queste opere, Egonu non rappresenta un popolo senza Stato: ne dipinge la dignità invisibile, il diritto a un’immagine, a un orizzonte condiviso. La sua sezione chiude la mostra non con un punto, ma con una sospensione: l’attimo prima che la storia riprenda a scorrere.

Poi la narrazione si apre alle città. Le fotografie architettoniche del dopoguerra e le copertine degli album Highlife raccontano Lagos come laboratorio di modernità cosmopolita. Un suono tenue attraversa la sala: la playlist di Peter Adjaye evoca l’energia urbana che il museo, per sua natura, non può contenere.

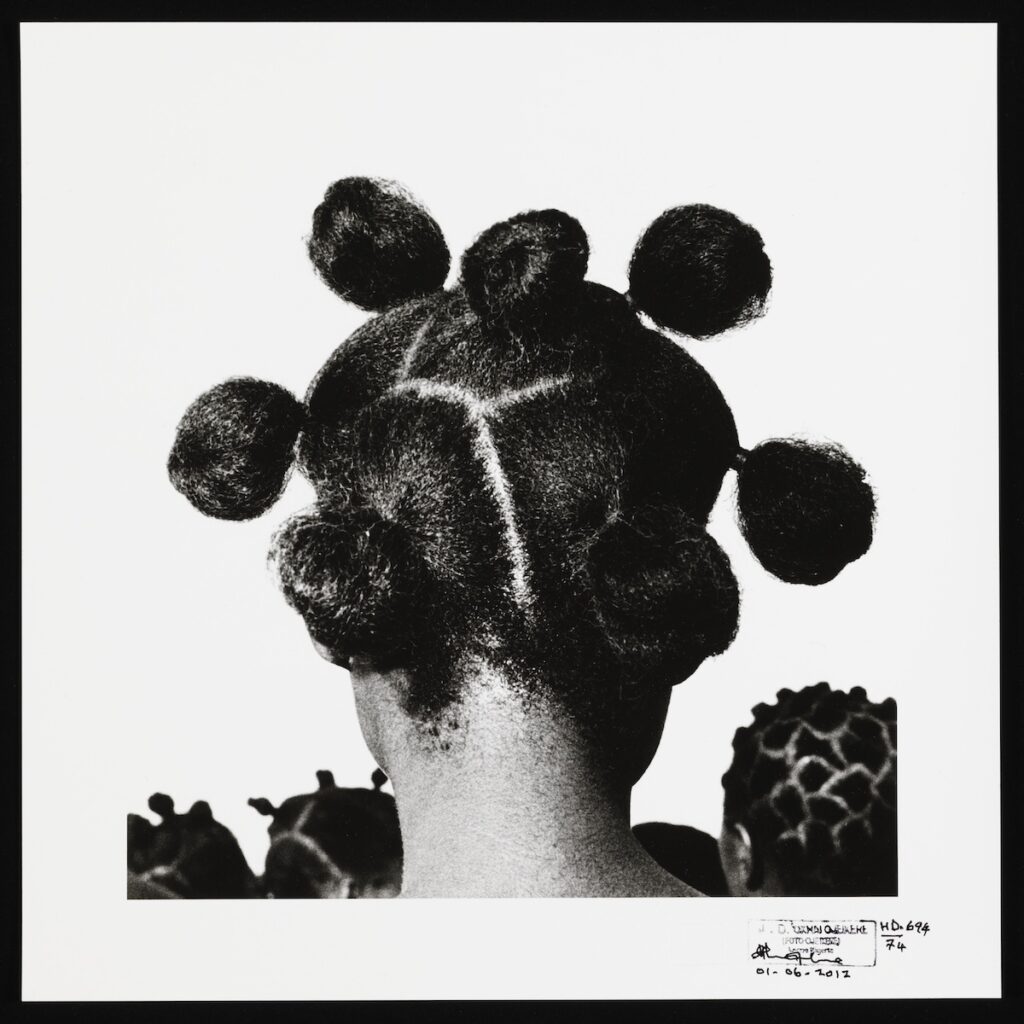

Eppure, nelle acconciature scolpite di JD ’Okhai Ojeikere, l’architettura torna al corpo: la città vive nei capelli delle donne, nella geometria di un gesto quotidiano.

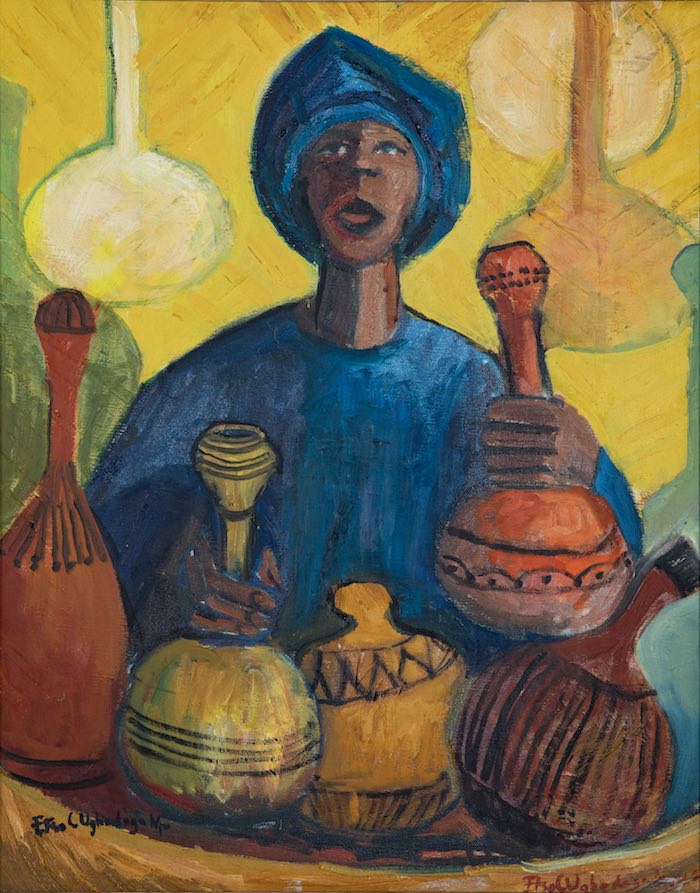

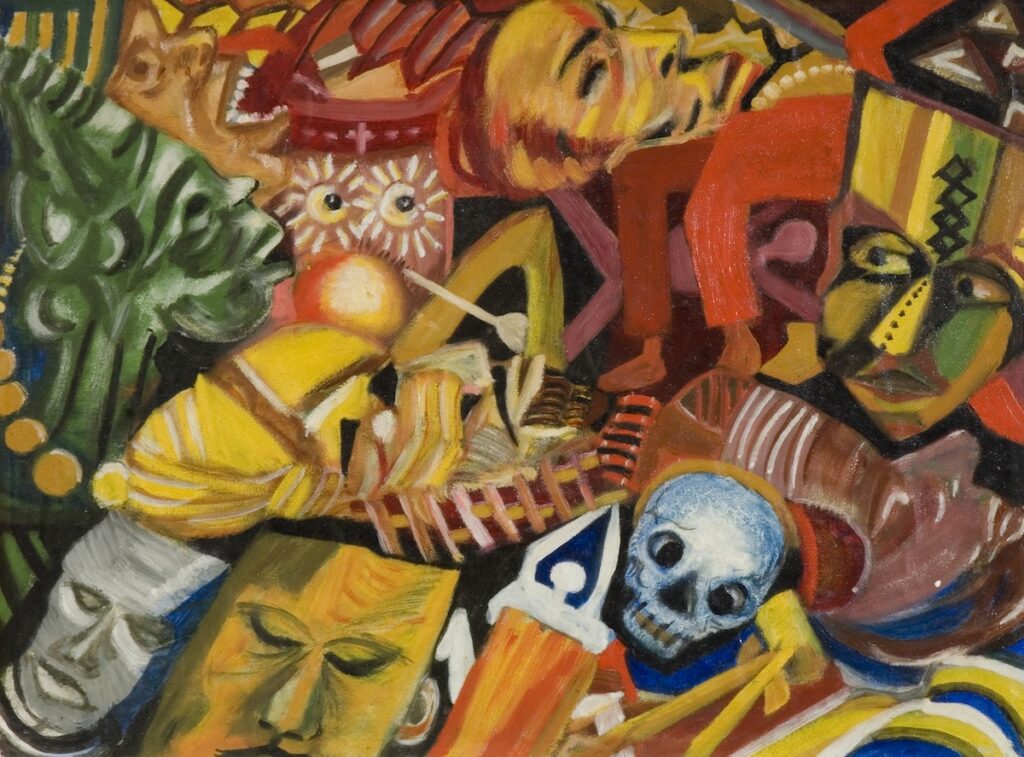

Intorno a lei, Twins Seven-Seven e Jimoh Buraimoh espandono la mitologia Yoruba in visioni dense, attraversate da spiriti e città interiori. In In the Palm of an Architect tutto si affolla: l’uomo e il dio coincidono, la forma esplode in segno. Qui la mostra ritrova la sua voce più profonda: la modernità come metamorfosi del suolo, l’immagine come forma respirante di una terra viva. In Twins, la visione mitica; in Buraimoh, la costruzione: due poli di una stessa energia creativa, quella modernità indigena che la mostra alla Tate riconsegna al suo respiro originario — un’arte che non imita, ma trasfigura, trasformando la memoria in materia che pulsa. Attorno a loro si dispiega una costellazione più ampia di presenze: da Ben Enwonwu, che tradusse il movimento del corpo in una grammatica scultorea di dignità e potere, a Uche Okeke, teorico della Natural Synthesis, per il quale l’arte doveva nascere dall’incontro tra segno tradizionale e modernità cosmopolita. Yusuf Grillo portò la luce del vetro e del blu indaco dentro il linguaggio pittorico, mentre Bruce Onobrakpeya trasformò la stampa in rito, facendo della matrice un altare di memoria. Nello stesso orizzonte, Clara Etso Ugbodaga-Ngu, tra le prime pittrici e insegnanti della scuola di Zaria, sperimentò un linguaggio di emancipazione femminile e formale; e Asiru Olatunde, con le sue incisioni su metallo, trasformò il gesto artigianale in scrittura cosmica, intrecciando il segno alla superficie come una preghiera di luce. Ladi Kwali, la grande ceramista, modellava la terra come si accarezza un’origine. Nei suoi vasi il gesto femminile tornava canto, il fango si faceva parola, e la continuità di un sapere antico trovava la propria voce nelle mani che la plasmavano. Più avanti, la mostra rallenta e si apre al sacro. Susanne Wenger, artista austriaca naturalizzata nigeriana, porta il modernismo verso il rito. Nei testi in catalogo, viene descritta come una figura di passaggio tra mondi, un’artista-sacerdotessa capace di entrare “nella sostanza stessa della cultura yoruba”. Il suo lavoro di restauro e costruzione dei santuari di Osun, realizzato con artigiani locali, segna la nascita del New Sacred Art Movement — un’arte nata in servizio al rito, non alla rappresentazione. Le sue sculture per i boschi sacri di Osogbo – figure nate dal suolo, quasi radici che si fanno corpo – sono reliquie di un’esperienza collettiva, residui di un’arte che non separa umano e divino.

Nel respiro di questa rinascita culturale si avverte anche la voce di Christopher Okigbo, poeta e musicista, morto giovane nella guerra del Biafra, come se la sua parola avesse consumato troppo presto il proprio fuoco. Nei suoi versi — «and the flute calls again / and the wailing drum» — si riconosce lo stesso battito che attraversa le opere di Osogbo: un canto di fondazione e di perdita. Okigbo cercò nella poesia ciò che gli artisti visivi cercavano nella forma: un linguaggio capace di unire l’antico e il moderno, il rito e la nazione nascente. La sua poesia, sospesa tra inglese e lingua igbo, tra sacro e profano, risuona come un altare verbale della modernità africana: una lingua che scava nel mito per reinventare il presente. “L’odore del sangue galleggia già nella nebbia lavanda del pomeriggio”: i suoi versi riempiono la stanza in cui campeggia Our Journey (1993) di Obiora Udechukwu: un vortice giallo che contiene eventi, figure, ricordi, come un diagramma del destino. Qui la pittura, sospesa tra simbolo e narrazione, lascia la mostra in uno stato di veglia: come se l’arte, invece di chiudere, prolungasse la ferita.

Mbari fu una cerimonia dell’appartenenza, il luogo dove una giovane nazione imparò a vedersi come origine e modernità insieme. Come ha scritto Okwui Enwezor in The Short Century: Independence and Liberation Movements in Africa, 1945–1994, (Prestel, 2001), il Mbari può essere inteso come una “cerimonia sociale e culturale” in cui arte e nazione coincidono, dando forma a una modernità africana consapevole di sé. Quella stessa cerimonia continua oggi nelle mani di Ndidi Dike e Peju Alatise, dove la materia torna rito e la scultura si fa respiro collettivo. Dike intreccia materiali industriali e simboli sacri, trasformando l’alluminio in reliquia, il ferro in memoria; Alatise plasma figure sospese, donne che sognano, come se la scultura potesse respirare il dolore e restituirlo come canto. Non sono appendici, ma aperture: la continuità di un pensiero che attraversa le generazioni.

Tutto in Nigerian Modernism ruota attorno a una domanda: che cosa significa essere moderni in un mondo erede della colonizzazione? Bonsu risponde in chiusura con un’immagine: questi sono gli artisti che emergono dall’altra parte della violenza, non per cancellarla ma per riscriverne la forma. Il modernismo diventa allora linguaggio della sopravvivenza, la prova che ogni nazione si costruisce anche attraverso la propria arte.

Alla fine del percorso, tornando verso la luce del corridoio, si percepisce un respiro: il suono profondo della terra che si riapre. Forse è questo che la mostra insegna: che la modernità non è una cima, ma un suolo. Come scrive Mbembe, “ogni civiltà si riconosce nel modo in cui custodisce le sue rovine.” Nigerian Modernism le custodisce non per nostalgia, ma per continuità. È una mostra che non chiude, ma riapre, non celebra, ma interroga; che ci ricorda, con la forza quieta dell’argilla, che il respiro dell’arte è – da sempre – il respiro del suolo.

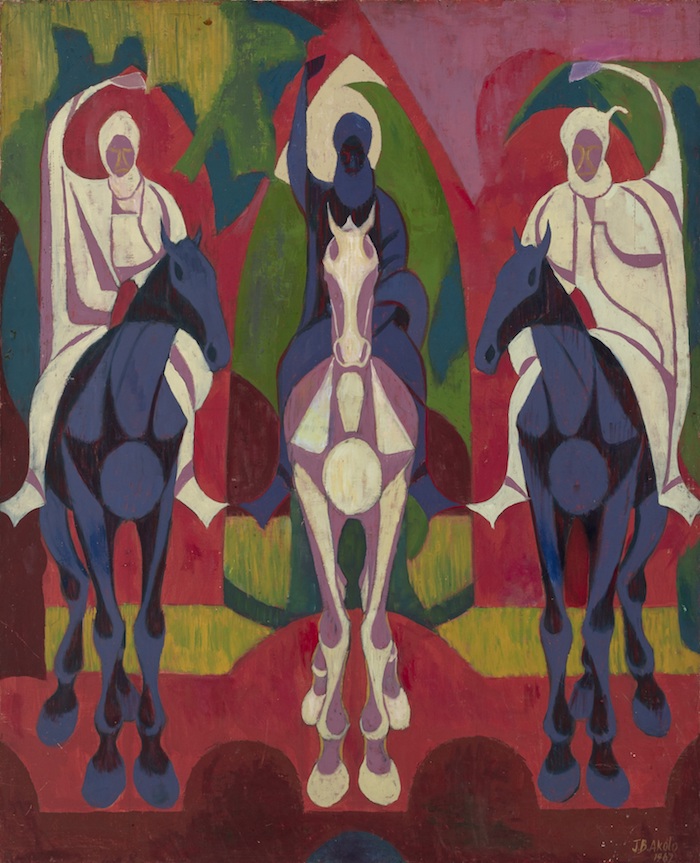

Cover: Ben Enwonwu, The Durbar of Eid-ul-Fitr, Kano, Nigeria 1955. © Ben Enwonwu Foundation. Private Collection

The Breath of the Soil. Notes on Nigerian Modernism at Tate Modern

Text by Rita Selvaggio —

In the Switch House at Tate Modern, within the rooms devoted to Nigerian Modernism, light does not fall: it rises — a breath drawn upward from the soil itself. It is a light that moves through the works like an earthly memory, a radiance that expands from the heart of matter. Curated by Osei Bonsu with Bilal Akkouche, the exhibition is more than a display: it is a laboratory of history, a reflection on the possibility of building a nation through its own images.

“Celebrating the originality of Nigerian art in all its power and vitality,” Bonsu writes in the catalogue, reminding us that African modernity is neither a loan nor a translation, but an invention — an autonomous flowering born of the encounter between European techniques and indigenous memory, of the desire to redefine the visible from the ground up. Developed through years of research carried out during the pandemic in the African holdings of the universities of Birmingham, York, and Chichester, the exhibition confronts a crucial question: how to restore to Nigerian art its denied modernity, releasing it from the ethnographic categories that imprisoned it for decades. The British press — The Guardian and beyond — has underlined how ambitious and contradictory this exhibition is: too expansive to be contained in a single glance, and necessary precisely for that reason. Its allure lies in its irresolution, in the attempt to read a century of history through works that refuse to be disciplined.

The journey opens with Aina Onabolu, the first to sense that mastering Western techniques could become a political act. In his disciplined realism, learned between Lagos, London and Paris, there is no obedience to the canon but a desire to overturn it from within, to bend the rule to his own breath. In his early-twentieth-century portraits — men and women of the Lagos elite, lawyers, teachers, figures of a rising bourgeoisie — Onabolu translates the academic pose into a language of pride and emancipation. Each face, immersed in a severe and precise light, seems to return to the African subject the possibility of finally seeing himself through his own gaze.

In A Short Discourse of Art (1925) he writes that realism is a “language of freedom”: a terse phrase that contains the essence of his path. To master the Western form, only to breathe another memory into it, is to affirm that modernity belongs to no one— that it can germinate wherever the hand finds a face to recompose. In his painting, technique becomes consciousness, and the surface opens like a threshold: the image does not represent, it generates. By deliberately choosing the European pictorial tradition over Yoruba sculptural conventions, Onabolu does not renounce his origin — he transforms it into humus, fertile ground for another vision of the self.

Akinola Lasekan, his pupil and successor, carried that inheritance further. In his paintings from the 1940s and 1950s — Ajaka of Owo, Ogedengbe of Ilesha, ritual dances and court scenes — the African body is no longer an object of representation but a mythic figure, a presence that speaks the language of epic. Lasekan turns painting into a narrative that interlaces document and legend, chronicle and myth, until the borders between history and vision dissolve. In his illustrations for Nnamdi Azikiwe’s West African Pilot, satire becomes a weapon and portraiture an act of resistance: a civic chronicle that unmasks power and nurtures the consciousness of independence. Around his Lagos studio, founded with the sculptor Justus D. Akeredolu, a small republic of images took form — a place where Yoruba tradition met urban modernity, where colour became testimony. Kings, warriors, mothers, ancestors: their figures restore to Nigeria the pride of its own face.

In these canvases, pictorial matter becomes chant and invocation — an alliance of pigment and memory in which history merges with myth to reaffirm the right to exist. Within this same horizon move Lamidi Olonade Fakeye, who fuses Christian iconography with Yoruba sculpture, and Olowe of Ise, whose carved door — shown at Wembley in 1924 — overturns the hierarchy of the colonial gaze: the British official no longer dominates the scene, but pleads before the king. In those refined woods, carved with the traditional adze and with modern tools, a symbolic passage is fulfilled: sculpture becomes a writing of resistance, tradition an avant-garde.

From this weave of voices — Onabolu, Lasekan, Fakeye, Olowe — a genealogy of freedom emerges, a modernism that breathes from the soil rather than the air. For them, modernity is not an external conquest but an interior space: the point where European technique bends to African memory and colonial history becomes living, malleable matter. From this fertile, contradictory and luminous ground will rise the next generation — that of Ben Enwonwu, ready to make African modernity vibrate between dance and myth, between mask and queen.

Alongside them, the photographs of Jonathan Adagogo Green document the complexity of a time of transition. They portray the Oba of Benin after the devastation of 1897: the deposed ruler, in chains, aboard a British yacht. Green, a photographer in the service of the colonial administration, unwittingly records the moral fracture of an empire and the wounded dignity of a kingdom. His images oscillate between exposure and compromise, as though the modern were born already contaminated.

A carved panel by Olowe of Ise depicts the meeting between the Ogoga of Ikere and Captain Ambrose: this time the coloniser appears as a supplicant before the king. It is a gesture of subversion that uses traditional sculpture to politicise the representation of power. It is no coincidence that the exhibition avoids the looted bronzes; instead, it chooses to resume the story where it was broken off — from the gestures of those who sought to stitch forms and techniques into a new horizon.

The next passage leads to Ben Enwonwu, the artist who embodies the contradictions between national pride and imperial belonging. His Negritude, metaphorically and visually the exhibition’s guiding image, translates dance into painting: bodies multiplying like waves, pigments turning into rhythm. Inspired by the nights at Lagos’s Caban Bamboo Club, Enwonwu attempts to paint the very sound of movement. Yet his figure remains ambiguous: in 1956 he painted Queen Elizabeth II, embodying both the arrival of an independent Nigeria and the continuing values of the Commonwealth. His art crosses the boundary between myth and power, between freedom and deference.

From here arises the tension that runs through the entire exhibition: modernity as an unstable, never-pacified equilibrium.

Unlike Enwonwu, the young artists of the Zaria Art Society — founders of Natural Synthesis — rejected every imposed language and sought to decolonise vision itself. In 1958 they gathered to reinvent art education in Nigeria: their revolution was silent and radical, a way of thinking of freedom as an unfolding process. As the curator writes, “the artists of this generation drew on the emancipatory potential of both tradition and modernity to forge a new language rooted in Pan-African unity.”

For them, memory is not nostalgia but a generative force: myth becomes a political gesture, symbol becomes the language of independence. Painting does not represent — it acts; form itself becomes liberation.

In the works of Uche Okeke and Demas Nwoko, painting becomes a space of resistance: amphibians, soldiers, unmasked dancers populate a world trembling with urgency, as if the canvas could contain the anxiety of a nation in transformation.

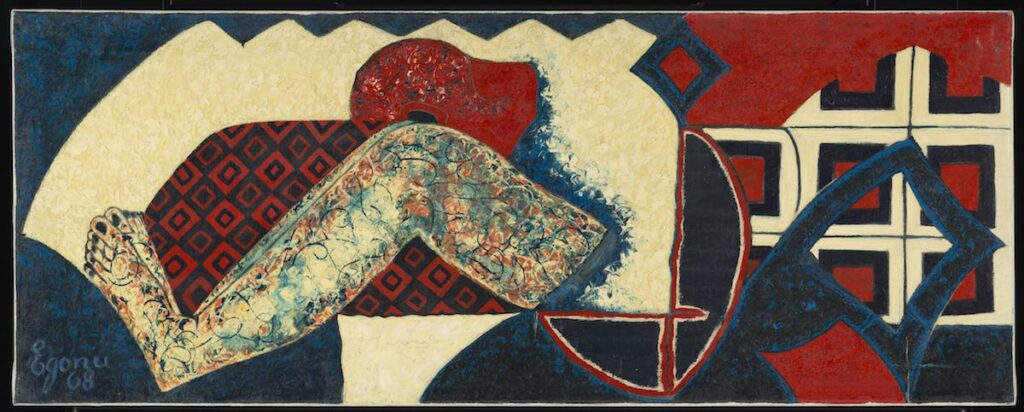

Within this constellation of tensions appears Uzo Egonu, a painter from Onitsha who moved to London as a young man. His canvases — Cityscape, Stateless People, Village with Church — seem seen through a lens that bends space: buses crossing Piccadilly, solitary figures, a geometric unease that belongs neither to Lagos nor to London. Egonu embodies the other face of modernity — diaspora as a permanent condition. Rather than seeking synthesis, his language embraces coexistence, letting differences remain in tension, like the memory of one who lives elsewhere.

In Egonu, modernity takes the form of an inner exile: broken lines, wavering architectures, figures without roots. In the Stateless People series (c. 1976–1980), he faces displacement as a universal condition — not only political but ontological. The figures appear suspended in fragmented spaces, neither earth nor sky, as though painting itself were searching for a place to belong. The geometric contours that define the bodies dissolve into an emotional cartography of the diaspora: not a landscape of loss, but a topography of survival. In these works, Egonu does not portray a people without a state — he paints their invisible dignity, their right to an image, to a shared horizon. His section closes the exhibition not with a full stop, but with a suspension: the instant before history begins to flow again.

Then the narrative opens toward the city. Post-war architectural photographs and Highlife album covers portray Lagos as a laboratory of cosmopolitan modernity. A faint sound drifts through the gallery: Peter Adjaye’s playlist evokes the urban energy that the museum, by its nature, cannot contain.

And yet, in the sculpted hairstyles of JD ’Okhai Ojeikere, architecture returns to the body: the city lives in the women’s hair, in the geometry of a daily gesture.

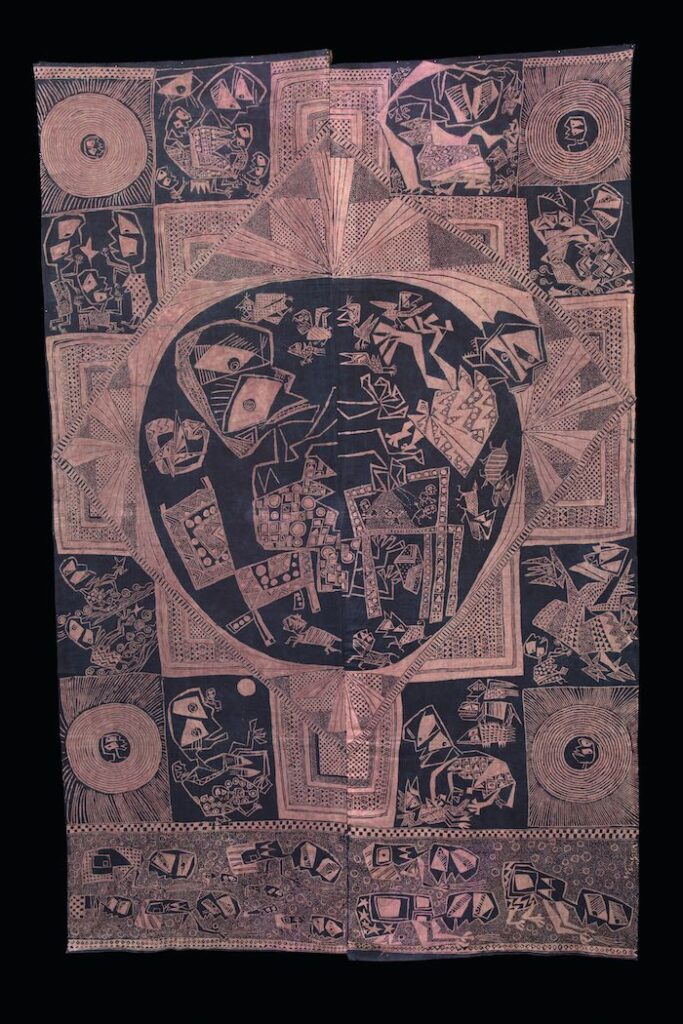

Further on, the exhibition slows and opens to the sacred. Susanne Wenger, an Austrian-born artist who became Nigerian by choice, leads modernism toward ritual. In the catalogue she is described as a figure of passage between worlds — an artist-priestess capable of entering “the very substance of Yoruba culture.” Her work of restoring and rebuilding the Osun shrines, carried out with local artisans, marks the birth of the New Sacred Art Movement — an art born in service of ritual, not representation. Her sculptures for the sacred groves of Osogbo — figures rising from the soil, roots transfigured into bodies — are relics of a collective devotion, the remains of an art that never separates the human from the divine.

Around her, Twins Seven-Seven and Jimoh Buraimoh expand Yoruba mythology into dense visions, crossed by spirits and inner cities. In In the Palm of an Architect everything crowds together: man and god coincide, form explodes into sign. Here the exhibition rediscovers its deepest voice — modernity as a metamorphosis of the soil, the image as a breathing form of living earth. In Twins, the mythical vision; in Buraimoh, construction: two poles of the same creative energy, that indigenous modernity which the Tate exhibition returns to its original breath — an art that does not imitate but transfigures, turning memory into pulsing matter.

Around them unfolds a wider constellation of presences: Ben Enwonwu, who translated bodily movement into a sculptural grammar of dignity and power; Uche Okeke, theorist of Natural Synthesis, for whom art had to arise from the meeting of traditional sign and cosmopolitan modernity; Yusuf Grillo, who brought the light of stained glass and indigo blue into painting; Bruce Onobrakpeya, who transformed printmaking into ritual, making the printing plate an altar of memory. Within this same horizon, Clara Etso Ugbodaga-Ngu — among the first women painters and teachers at the Zaria school — experimented with a language of female and formal emancipation; and Asiru Olatunde, with his engravings on metal, turned the artisanal gesture into cosmic writing, intertwining sign and surface like a prayer of light.

Ladi Kwali, the great ceramist, shaped the earth as one might caress an origin. In her vessels, the feminine gesture became song, clay turned to word, and the continuity of ancient knowledge found its own voice in the hands that shaped it.

In the breath of this cultural rebirth, one also hears the voice of Christopher Okigbo — poet and musician, who died young in the Biafran War, as if his words had burned through their own fire too soon. In his verse — “and the flute calls again / and the wailing drum” — one recognises the same pulse that runs through the works of Osogbo: a song of foundation and of loss. Okigbo sought in poetry what visual artists sought in form — a language able to unite the ancient and the modern, the ritual and the newborn nation. His poetry, suspended between English and Igbo, between sacred and profane, resounds as a verbal altar of African modernity: a language that delves into myth in order to reinvent the present.

“The smell of blood already floats in the lavender mist of afternoon.” His words fill the room where Obiora Udechukwu’s Our Journey (1993) stands — a yellow vortex containing events, figures, memories, like a diagram of destiny. Here painting, poised between symbol and narration, leaves the exhibition in a state of wakefulness — as though art, instead of ending, kept the wound breathing.

Mbari was a ceremony of belonging — the place where a young nation learned to see itself as both origin and modernity. As Okwui Enwezor wrote in The Short Century: Independence and Liberation Movements in Africa, 1945–1994 (Prestel, 2001), Mbari can be understood as a “social and cultural ceremony” in which art and nation coincide, giving form to an African modernity conscious of itself. That same ceremony continues today in the hands of Ndidi Dike and Peju Alatise, where matter returns to ritual and sculpture becomes collective breath. Dike weaves industrial materials and sacred symbols, turning aluminium into relic, iron into memory; Alatise moulds suspended figures, dreaming women, as if sculpture itself could breathe pain and return it as song. They are not appendices, but openings — the continuity of a thought that crosses generations.

Everything in Nigerian Modernism revolves around a single question: what does it mean to be modern in a world that inherits colonisation? Bonsu closes with an image: these are artists who emerge on the far side of violence, not to erase it but to rewrite its form. Modernism thus becomes a language of survival, the proof that every nation is also built through its art.

At the end of the path, returning toward the corridor’s light, one perceives a breath — the deep sound of the earth reopening. Perhaps this is what the exhibition teaches: that modernity is not a summit, but the soil from which everything begins again. As Mbembe writes, “Every civilisation is recognised by the way it tends to its ruins.” Nigerian Modernism tends to them not out of nostalgia, but out of continuity. It is an exhibition that does not close but reopens, that does not celebrate but questions — reminding us, with the quiet strength of clay, that the breath of art has always been the breath of the soil.

Cover: Ben Enwonwu, The Durbar of Eid-ul-Fitr, Kano, Nigeria 1955. © Ben Enwonwu Foundation. Private Collection