English version below

Intervista di Sara Benaglia / Mauro Zanchi —

Sara Benaglia / Mauro Zanchi: Cosa si sta soffocando ora (nell’era di internet, dei cellulari e della sovrabbondanza di simulacri) del potere che veniva attribuito alle immagini nel passato?

EK: Al momento il potere delle immagini deriva soprattutto dalla loro quantità e molteplicità. Lo si vede anche online, in particolare sui social media e sulle piattaforme in cui le persone si presentano e si copiano a vicenda. Non c’è niente di sbagliato in questo, ma determina un comportamento stereotipato con la fotografia e le immagini: lo stesso tipo di selfie, lo stesso tipo di filtri sui selfie, lo stesso tipo di fotografia di cibo, le stesse immagini scattate quando ci si annoia e le medesime etichette per indicare il fatto di essere annoiati. Non è che un’immagine salti fuori da questa massa di immagini, si tratta piuttosto di un accumulo dei medesimi tipi di immagine che fanno un determinato movimento. In generale. Più specificamente, penso che in quest’epoca la maggior parte delle immagini sia già stata scattata. Soprattutto in fotografia, che è un mezzo così veloce, tutto ha anche un certo stile: il ritratto, il bianco e nero, il paesaggio, il reportage, la fotografia documentaria. Questi stili sono stati molto sviluppati. Oggi è molto più interessante la storia che si cela dietro una fotografia. Sono state scattate molte immagini, ma non tutte le storie dietro ogni fotografia sono state ancora raccontate, e questa è una cosa interessante. Quando si scatta una fotografia a caso e ci si concentra su di essa per un sacco di tempo, e si guarda di nuovo la foto il giorno dopo, si può immaginare quale tipo di storia ci sia dietro questa foto, oppure si può fantasticare intorno ad essa. Ma in alcuni casi dietro certe fotografie c’è anche una storia vera e propria e penso che anche l’aspetto narrativo sia molto interessante. In passato la qualità di un’immagine doveva solo dare risultati, doveva impressionare, ma oggi a fare questo può anche essere la storia che c’è dietro.

SB / MZ: Partecipi a costituire un’arte della contro-informazione (o meglio, per dirla alla Deleuze, realizzi “atti di resistenza”)?

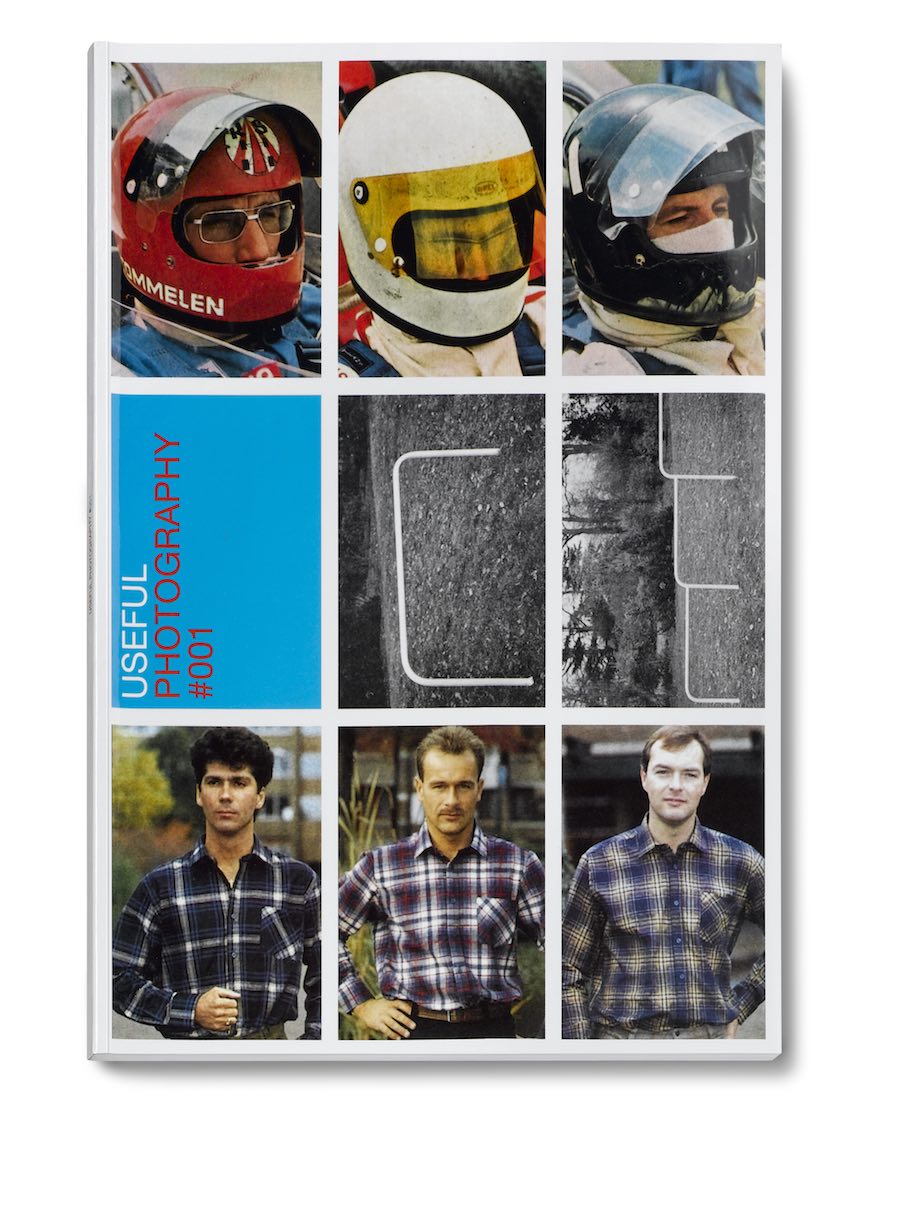

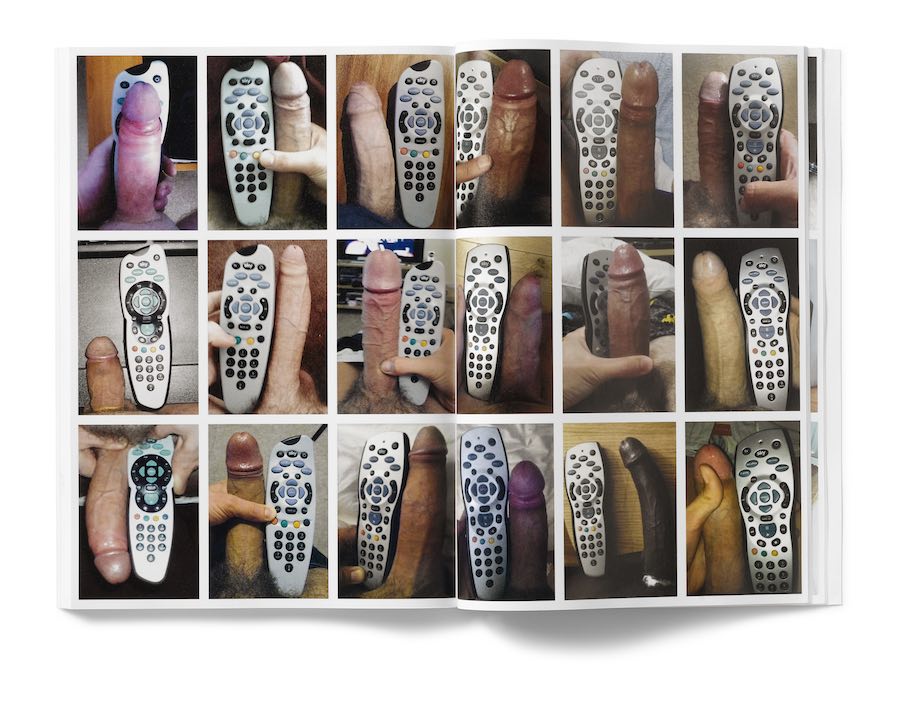

EK: Nel mio caso lavoro molto con le immagini, ma non sono un fotografo con la macchina fotografica o altro. Per me è sempre interessante guardare le immagini da outsider e guardare i sistemi da essa prodotti. Il fatto che ci sia un tale sovraccarico di immagini e che la grande maggioranza di esso sia molto stereotipata mi porta come artista a reagire a questo e a fare una dichiarazione. Con la pubblicazione Useful Photography mostro sempre determinate serie o stili di fotografie usate con un certo scopo, ma le tolgo dal loro contesto. Quando le immagini rimangono online non le guardi con molta precisione. Ma quando le togli dal loro contesto e le fai saltare in aria e le appendi alla parete, cambi il contesto di queste immagini e poi all’improvviso ricominci a guardarle. Una volta ho trovato una brochure, consegnata da un postino. Era una brochure di carne a buon mercato con immagini di filetto di pollo e bistecche. Ho scannerizzato un’immagine e l’ho stampata molto in grande, tipo due metri per un metro, l’ho appesa al muro, proprio l’immagine del filetto di pollo. Quel pezzo di pollo crudo era disgustoso, molto nudo. Ma appeso lì, sul muro del salotto, per quanto bizzarro, ti consente di guardarlo in modo diverso. Ho realizzato la rivista Useful Photography #13 dove ho preso da internet molte fotografie di cazzi, immagini in cui diversi uomini mostrano le dimensioni del proprio cazzo mettendolo in posa vicino a qualcosa, come una tazza di caffè o una matita, o una bottiglia di bagnoschiuma o un telecomando. Queste immagini sono usate per Snapchat o Tinder o per questo tipo di piattaforme. Quando le trovi e le raggruppi tutte, le tiri fuori dal loro contesto, poi all’improvviso la gente vede quanto è folle internet. È bizzarro. Ci sono così tante immagini di cazzi con il telecomando accanto! Lo studio di un artista filtra anche questo, lo scompagina e lo porta fuori dal suo contesto. Questo è un atto di riappropriazione, dove si costringe davvero la gente a vedere le cose come stanno. Siamo consumatori di immagini di massa, fast-images: c’è un tale sovraccarico che consumiamo le immagini senza sentirne più il sapore. Le ingoiamo e basta, ma non le guardiamo più.

SB / MZ: Come ti rapporti rispetto alle immagini che provengono dall’informazione televisiva, dalla comunicazione, insomma dalla esponenziale moltiplicazione delle immagini atta a mettere in azione i più efficaci risultati di accecamento?

EK: Ho un background in comunicazione e grafica. Conosco perfettamente le regole di questo tipo di immagini, e ho anche lavorato nel settore per molto tempo. Ma per me è importante il fatto che la gente costruisca sempre questo tipo di immagini, cioè il fatto che non si tratti di immagini spontanee ma costruite. È una cosa che ho sempre odiato. E per questo cerco di evitare di farla. Penso anche che ora come ora queste regole non siano più così forti. Una volta c’era un mondo professionale che generava questo tipo di immagini e che aveva tutte le tecniche, l’artigianalità per lucidare le immagini, per renderle efficaci, bellissime. Ma al momento questo non c’è più. Voglio dire: il fatto che le lucidino non è sparito, ma al momento tutti possono fare questa operazione.

Instagram funziona come una propaganda. Ognuno porta avanti la sua propaganda personale attraverso il proprio account. E questo accade determinando cose buone e cattive. Instagram è usato in un modo completamente diverso da quello per cui era stato immaginato. L’idea era che si vede qualcosa, si scatta una foto e poi la si pubblica. Ma ora le foto sono una specie di pre-produzione, preparate apposta per essere caricate sugli account Instagram e sono così professionali e così raffinate che anche i dilettanti ora usano le medesime regole usate dalla ‘propaganda professionale’. È spaventoso quanto siano perfette le immagini al giorno d’oggi. Il fatto che con un filtro si possa invecchiare di dieci anni e che l’effetto sia anche piuttosto realistico e il fatto che questa operazione avvenga in tre secondi o il fatto che si possano gonfiare le labbra in due secondi senza chirurgia estetica sembra perfetto. Queste macchine sono fatte apposta per il beneficio personale, così che le persone si sentano meglio con sé stesse. Ma le persone sono davvero così?

SB / MZ: Si possono far sprigionare immagini interessanti dai cliché?

EK: Ci saranno sempre immagini un po’ estranee e ai margini, forse più complicate da capire, magari con storie interessanti alle spalle. Queste immagini possono influenzare le immagini cliché che si vedono ovunque. C’è una costante battaglia in corso tra di loro. Ma a volte hanno anche bisogno di persone che dimostrino le loro potenzialità. È necessario confrontare le immagini più cliché con quelle maggiormente alternative.

SB / MZ: Con Thomas Mailaender hai condiviso l’ideazione del divertentissimo Photo Pleasure Palace all’Unseen di Amsterdam. Che cosa è emerso di particolare e nuovo da questa esperienza?

EK: Ci sono festival d’arte, fiere d’arte, festival di fotografia, mostre, ma quello che mi chiedo è: come posso spingere i confini di nuovi modi di mostrare il lavoro? A volte in una galleria appendi qualcosa al muro in linea retta, lo guardi e magari non trovi più quel che cercavi. Per me è molto più interessante l’esperienza nell’interazione. È qualcosa che abbiamo davvero cercato di fare lì: spingere i confini di come si possono mostrare anche in modo diverso le immagini. In questo caso si trattava per lo più di immagini con cui oggi viviamo. Tutte le immagini ridicole che internet ci ha portato. Quindi c’era un muro con 500 immagini incorniciate e da 8 metri di distanza si poteva lanciare contro di esse un blocco di legno. Si poteva colpire una fotografia, rompere la cornice dopo di che questa veniva sigillata e si poteva portare a casa la foto di plastica. C’era una pedana elastica di 8×8 metri con una foto di Trump stampata sopra, così la gente poteva saltargli in faccia. Era simile a una mostra interattiva, per vedere come le persone possono sperimentare le immagini in un modo diverso.

SB / MZ: Come utilizzi la “fotografia vernacolare” ora che, con i social network, la sfera privata si confonde con quella pubblica?

EK: Come artista puoi usare qualsiasi immagine esistente. Ne vedi una, ti viene un’idea guardandola, te ne riappropri, la metti in un contesto diverso che diventa il tuo lavoro. Naturalmente c’è anche una certa linea da non oltrepassare. Oggi il confine tra pubblico e privato è molto labile: se si guarda online si possono trovare immagini di donne che partoriscono un bambino e tutto questo viene fotografato e messo su Facebook o altrove. È bizzarro quanto siano aperte le persone con il proprio immaginario fotografico privato: nessuno sa che chiunque può guardarlo e che tutti possono scaricarlo. Penso che ci sia una certa linea per cui si debba rispettare la privacy altrui e in un certo senso proteggere le persone da sé stesse, dai loro comportamenti strani a volte.

SB / MZ: In una sua intervista abbiamo letto questa interessante metafora: “è nel caos del giardino posto sul retro delle nostre case che ci sentiamo liberi di andare in giro sbracati ed è lì che si crea, anche facendo errori. Così iniziamo a guardare le cose in modo differente e abbiamo nuove idee”. Cosa hai trovato nel disordine del giardinetto nascosto dietro la facciata principale della tua ricerca?

EK: Vedo giovani professionisti o studenti che usano solo il giardino posto di fronte a casa, dove hanno il lavoro finito. Lì mostrano il proprio lavoro o il sito web o il portfolio al resto del mondo. Spesso questi mostrano lavori creati solo nel giardino frontale, ma secondo me le opere più interessanti si creano nel giardino posteriore. Il retro di una casa mette in imbarazzo, perché lì vi sono riposti spazzatura e un certo caos. Per questo la gente lo recinta, perché si vergogna di quello che gli altri potrebbero vedervi. Sul retro sono depositati i progetti incompiuti. È ovviamente una metafora, per dire che nel disordine ci si può sbizzarrire e trovare idee senza che la gente se ne accorga. Quando fai qualcosa dal caos puoi poi portarla nel giardino di fronte e mostrarla. Molte persone non vanno più sul retro.

SB / MZ: Secondo te come mai la gente ha continuamente l’istinto o la propensione a dare testimonianza fotografica della propria esistenza, anche delle idiozie, visto che poi per l’80 per cento dei casi le immagini poi giacciono nelle memorie dei PC, degli smartphone o altro, senza essere più viste e fruite? Cosa è cambiato dal tempo in cui la gente in media conservava le fotografie in circa sette album fotografici nel corso di una vita intera, ora che invece non si fanno più foto per conservare memorie, ma per condividerle in tempo reale col mondo dell’effimero?

EK: Questa è una domanda interessante. Credo che la questione abbia molto a che fare con quella che definisco “propaganda privata”. Al tempo della fotografia analogica la famiglia teneva un album, per cui andava in vacanza, e faceva delle foto molto belle anche per provare di essere stata in Italia o in Francia e mostrava queste immagini ai suoi amici. Anche questa era una sorta di propaganda. Ma oggi la propaganda è quasi sempre in corso. Alla gente piace condividere con gli altri quanto è perfetta, quanto sia felice e quanto vadano bene le cose. È molto raro trovare immagini in cui qualcuno piange su Instagram, o immagini in cui qualcosa non va bene. Ho fatto una serie di fotografie con i miei figli quando erano piccoli. Li ho fotografati quando avevano il naso che sanguinava, perché hanno le narici molto sottili, quindi ho probabilmente 80 immagini di loro con il sangue che gli esce dal naso. Sono foto bellissime. Penso che siano bellissime. Ho pensato che questo fosse un momento perfetto da catturare, perché quando invecchieranno ne sentiranno la mancanza e non avranno più questo ricordo. Ma molte persone odiavano queste immagini, dicevano che si trattava di violenza contro i bambini. Mentre sono solo normali momenti di famiglia.

Interview with Erik Kessels

By Sara Benaglia and Mauro Zanchi —

SB / MZ: What is being stifled now (in the age of the internet, mobile phones and the overabundance of simulacra) of the power that was attributed to images in the past?

EK: At the moment the power of images comes mainly from their quantity and multiplicity. You see also online, particulartly on social media and platforms where people present themselves and copy each other. There is nothing wrong with this, but it leads to stereotypical behavior with photography and images: the same kind of selfies, the same type of filters over the selfies, the same kind of food photography, the same pictures taken when bored and the same tags to indicate being bored. It’s not that one image pops out of this mass of images, it’s rather an accumulation of the same types of images that make a certain movement. But this is in general. More specifically, I think that in this age most kind of images have already been taken. Especially in photography, that is such a quick medium, everything has also a certain style: like portrait, black and white, landscape, reportage, documentary photography. These styles have been very developed. Nowadays the story behind a photograph is much more interesting. Many images have been taken yet, but not all the stories behind every photograph have been told yet, and that is an interesting thing. When you just take a random picture and you concentrate on it for a long time, and you look again at the picture the next day, you can imagine which kind of story is behind it, or you can fantasize around it. But in some cases there is also a real story behind certain photographs and I think that the story-telling aspect is also very intriging. Because in the past the quality of an image was supposed to give results, to impress, but today it can be also the story that is behind it.

SB / MZ: Do you participate in constituting an art of counter-information (or rather, to put it in Deleuze’s words, you carry out “acts of resistance”)?

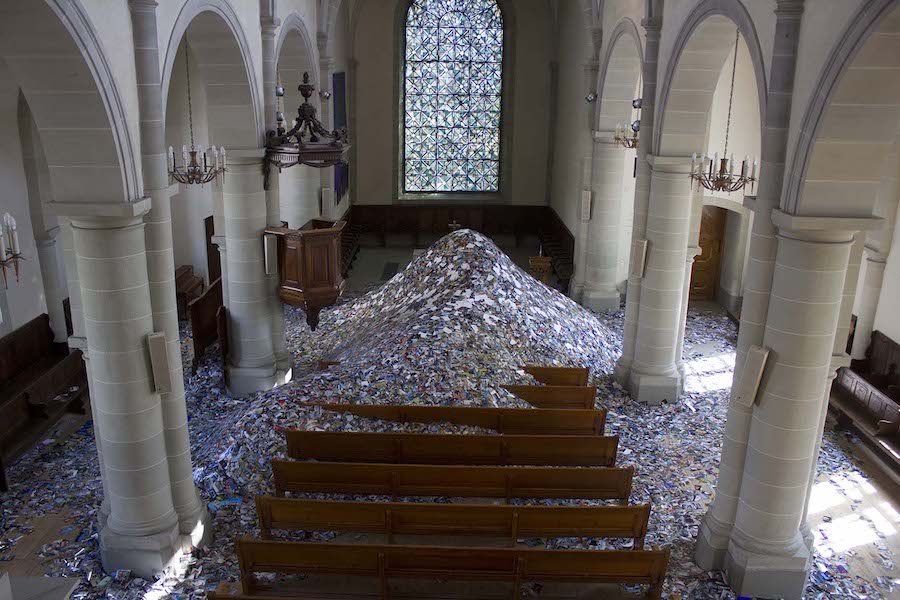

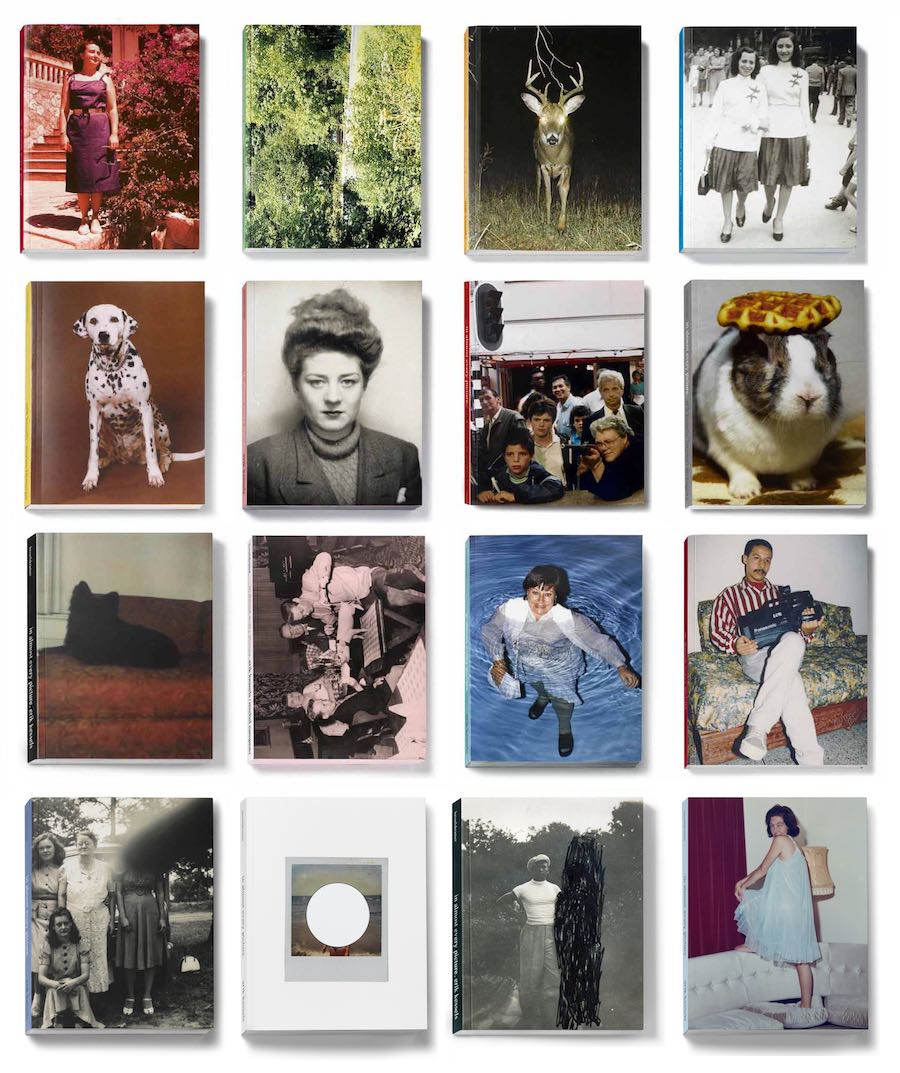

EK: In my case I work a lot with images, but I’m not a photographer with a camera or anything else. For me it’s always interesting to look at images as an outsider, and to look at the systems that it produces. The fact that there is such an overload of images and that the vast majority of it is very stereotypical leads me as an artist to react on that and to make a statement with that. With the publication Useful Photography I always show certain series or styles of photographs used with a certain purpose but I take them out of context. When images stay online you don’t look at them very precisely. But when you take them out of their context and you blow them up and you hang them on your wall you change the context of these images and then suddenly you start looking at them again. Once I found a brochure at a doorstep, delivered by a postman. It was a cheap meat brochure with images of chicken fillet and steaks. I scanned an image and printed it very big, like two by one meter, hang it on the wall, just the image of a chicken fillet. That raw piece of chicken looked disgusting, very naked. But when you have it on your wall and on your living room it’s quite bizarre because you start looking at it differently and that is an interesting thing to do. I made the magazine Useful Photography #13 where I took a lot of images of dick pics from the internet, which are images where several men are showing the size of their own dick with something next to it, with a cup of coffee or with a pencil, or with a shower bottle or a remote control. These images are used for Snapchat or Tinder or this kind of platforms. When you find them and group them all, you take them out of their context, then suddenly people look at how crazy the internet is. It’s bizarre. There are so many images with dicks with remote controls next to them! Artist’s practice filter that too, disrupt it and take it out of context. This is an act of re-appropriation, where you really force people to look at something as it is. We are mass or fast images consumer: there is such an overload that we consume images but we don’t taste them anymore. We just consume them, but we don’t look at them anymore.

SB / MZ: How do you relate to the images that come from television information, from communication, in short, from the exponential multiplication of images capable of putting into action the most effective results of blinding?

EK: I have a background in communication and graphic design. I know perfectly the rules of those kind of images, I also have been working in the industry for a long time. But for me it is very important the fact that people is always constructing these kind of images, that is, that they are not spontaneous but constructed images. It’s something I have always quite hated. So I always try to bypass that. I also think that at the moment these rules are not so strong anymore. Once upon a time there was a professional world that generated this kind of images, and that had all the techniques, the craftsmanship, to polish images, to make them very effective, very beautiful. But at the moment that is totally gone. I mean, the fact that they polish them is not gone, but at the moment everybody can do that. Instagram is like propaganda. It’s like personal propaganda through an Instagram account. With all the good and the bad things also. Instagram is used in a completely different way from the one it was attended to be. The idea was that you see something, take a picture and then you post it. But now pictures are kind of pre-produced to be uploaded on Instagram accounts and they are so professional and so polished that even amateurs now use the same rules of how ‘professional propaganda’ was done. Images are so perfect nowadays that is almost frightening. The fact that with a filter you can age yourself of ten years and it looks still quite realistic and you can do that in three seconds or the fact that you can just pump up your lips within two seconds and it looks perfect. But these machines are made for personal benefit, so that people feel better with what they are. But are they really like this?

SB / MZ: Can interesting images be released from clichés?

EK: Yes. There will always be images that are a little bit outsiders and from the fringe, perhaps more complicated to understand, maybe with more interesting stories behind. These images can influence the cliché images that you see everywhere. There’s an ongoing battle between them. But sometimes they need people to prove their potential. You need to confront the most cliché images with the most alternative ones.

SB / MZ: You shared with Thomas Mailaender the idea of the amusing Photo Pleasure Palace at Unseen in Amsterdam. What emerged, as was particular and new, from this experience?

EK: There are art festivals, art fares, photo festival, exhibitions but mostly what I look for is how I can push the boundaries of new ways of showing work. Sometimes in a gallery the time that you just hang something on the wall in the straight line you have to look at it and it’s maybe gone. For me the experience of interaction is much interesting. This is something that we really tried to do there: to push the boundaries of how you can show images in a different way. In this case they were mostly images that we live with nowadays. All the ridiculous images that internet brought us. So there was a wall with 500 framed images on there and from 8 meters distance you could throw a wooden block at them. You could hit a photograph, break the frame after which it was sealed and you could take the sealed plastic picture back home. There was an 8×8 meters jump with a picture of Trump printed on it, so people could jump in his face. It was more like an interactive exhibition, to try to see how people can experience imagery in a different way.

SB / MZ: How do you use “vernacular photography” now that, with social networks, the private sphere is confused with the public sphere?

EK: As an artist you can use any image that is there. If you make an idea with it, you re-appropriate it, you put it in a different context that becomes your work. Of course there is also a certain line not to be crossed. Nowadays there is such a blurred line between private and public: if you look online you can find images of a all session of women giving birth to a baby and all that is photographed and put on Facebook or wherever. It’s bizarre how open people are with their own private photographic imagery, not knowing that anybody can look at that and that everybody can take it off. I think that there is a certain line where you have to respect the privacy and almost protect people from themselves, from their own strange behaviors sometimes.

SB / MZ: In an interview with you I read this interesting metaphor: “it is in the chaos of the garden at the back of our homes that we feel free to wander around unhinged and that is where we create ourselves, even making mistakes. So we start looking at things in a different way and we have new ideas”. What did you find in the clutter of the small garden hidden behind the main facade of your research?

EK: I see young professionals or students that only use their front garden, where they have their finished work. The front garden is where you really show your work/website/portfolio to the rest of the world. But often they have created these works only in the front garden, while for me you create the most interesting work in the back garden. This is a place that the most of the time you are embarrassed about, because there is a lot of rubbish there, there is chaos, people built a fence around it, because they are ashamed of what is there. And there’ s a lot of unfinished project in this place. This is a metaphor since there you can fiddle around with things and come up with ideas without people seeing it. And when you make something there, then you can bring it to the front garden and you show it. But a lot of people don’t go to that backyard anymore.

SB / MZ: In your opinion, why do people constantly have the instinct or the propensity to give photographic evidence of their existence, even idiocy, since 80% of the time the images lie in the memories of PCs, smartphones or other devices, without being seen and enjoyed anymore? What has changed since the time when people kept photographs in an average of about seven photo albums over a lifetime, and now that they no longer take photos to preserve memories, but to share them with the world of the ephemeral?

EK: This is an interesting question. I think this has a lot to do with what I previously mentioned as “private propaganda”. Nowadays you can do this constantly. It has always been possible, but with analog photography the family had a family album, they went on holidays, they made very beautiful pictures just as an evidence of the fact that they had been in Italy or France and they showed these pictures to their friends. This was also a kind of propaganda. But nowadays the propaganda is constantly on. People like to share with others how perfect they are, how happy they are and how good things are going with them. It’s very rare that you find images where somebody is crying on Instagram, or images where something is not going well. I made a series of photographs with my children when they were young. I took pictures of them when they had a bloody nose, because they have very thin nostrils, so I probably have 80 pictures of them with blood coming out of their noses. These are beautiful pictures. I think that they are beautiful. I thought this was a perfect moment to capture, because when they will get older they will miss them and they won’t have this memory anymore. But a lot of people hated these images, because they said it was violence against children, while they are just normal family moments.