English text below

Ho deciso di parlare di una delle mie più recenti opere: una serie dal titolo “It’s always so hard to admit that things are different than what we had believed at first sight” perché secondo me, nella sua semplicità possiede molte caratteristiche emblematiche del mio lavoro.

Da alcuni anni la mia ricerca tenta di analizzare e problematizzare alcuni aspetti specifici dell’arte e dell’oggetto d’arte. Oggetto inteso in modo molto ampio.

Spesso le mie riflessioni partono dalla scelta di alcune forme, quasi sempre goffe, di materiali per me affascinanti a causa dele loro caratteristiche di iper-materialità, e di oggetti capaci di comunicare a lunghe distanze immaginari stratificati e differenti.

Poi c’è un lato del mio lavoro che invece torna spesso a riflettere sulla genealogia dell’opera stessa. Sempre più spesso però la necessità di approfondire questi discorsi si intreccia ad alcune riflessioni circa la percezione delle opere da parte delle differenti tipologie di pubblico alle quali queste si relazionano.

Ho sempre provato molta fascinazione nei confronti di un particolare momento in cui osservando alcune opere d’arte lo spettatore riesce a sentirsi coinvolto in prima persona.

Vedi l’opera, leggi il titolo e ti senti coinvolto. Sentirti coinvolto ti sconvolge per un attimo. Quando provo a ricreare questo speciale legame empatico che lega opera e spettatore e a ricostruirne la particolare dinamica relazionale, cerco di attuarla non attraverso un’ intesa, una conferma o una complicità, ma piuttosto attraverso un fraintendimento oppure una delusione.

Se dovessi sintetizzare in una frase tutto ciò di cui tratta la mia ricerca, direi che si occupa di comprendere e calcolare una distanza: la distanza tra opera e spettatore, oppure la distanza che c’è tra essa ed il suo titolo. La distanza che separa l’artista dal suo lavoro e la distanza che riesce a percorrere un’ opera continuando a comunicare se stessa.

La tematica affrontata in “It’s always so hard to admit that things are different than what we had believed at first sight” è ben descritta dalla frase che gli da il titolo: é sempre molto difficile ammettere che le cose sono diverse da ciò che avevamo creduto a prima vista.

L’esigenza di concentrarmi su questo concept è nata in modo del tutto naturale; spesso sono le persone ad inspirarmi maggiormente, con i loro errori, la loro miseria e la loro umanità. Nella mia mente la mia vita professionale, le mie riflessioni circa il linguaggio dell’arte, le mie delusioni, la mia vita privata, i miei stessi errori e quelli di persone che non conosco nemmeno, amici di amici, si mescolano, diventano un unico fardello di esperienze che faccio mie; che sento mie, e così nasce il senso di necessità e l’intuizione da cui ha origine ogni mia opera.

Formalmente mi faccio ispirare dalle cose che mi circondano, dalle mie esperienze pregresse ed infantili, dal mio quotidiano, da ciò che vedo ogni giorno tra semafori e tunnel stradali, da quello che gli algoritmi dei diversi social che utilizzo mi suggeriscono; la forma delle cose per me è quasi sempre una scusa per enfatizzare un determinato discorso, approfondire un processo, deviare l’attenzione del pubblico in modo da poterlo selezionare, così da riconoscere gli interlocutori più attenti e sensibili.

In quest’opera convivono due diverse facce: una suggerisce tridimensionalità, l’altra bidimensionalità. Ci ricordano l’unico punto comune a due epoche o realtà completamente differenti, quasi opposte. Faccio un piccolo esempio per spiegare questo attimo in comune, un esempio random, il primo che mi viene in mente preso dalla mia esperienza: se dovessi definire qual’è il momento che hanno in comune il triassico e l’anno 2028, direi che è una piovosa giornata di ottobre del 1991. La mattina ero andato a scuola, e come ogni mattina fino alla mia terza elementare avevo cercato di scappare, con mio padre che mi attendeva fuori pronto a riportarmi a scuola e la bidella che mi rincorreva spaventata. Ma questo è successo al mattino. Ora è pomeriggio. Da qualche parte a Milano, una persona speciale nasceva, ma io non ne avevo idea, avevo 8 anni ed ero il centro assoluto del mio universo. Stavo studiando la preistoria, e su Italia1 trasmettono Robocop.

In quel pomeriggio il triassico ed il 2028 sono avvenuti contemporaneamente.

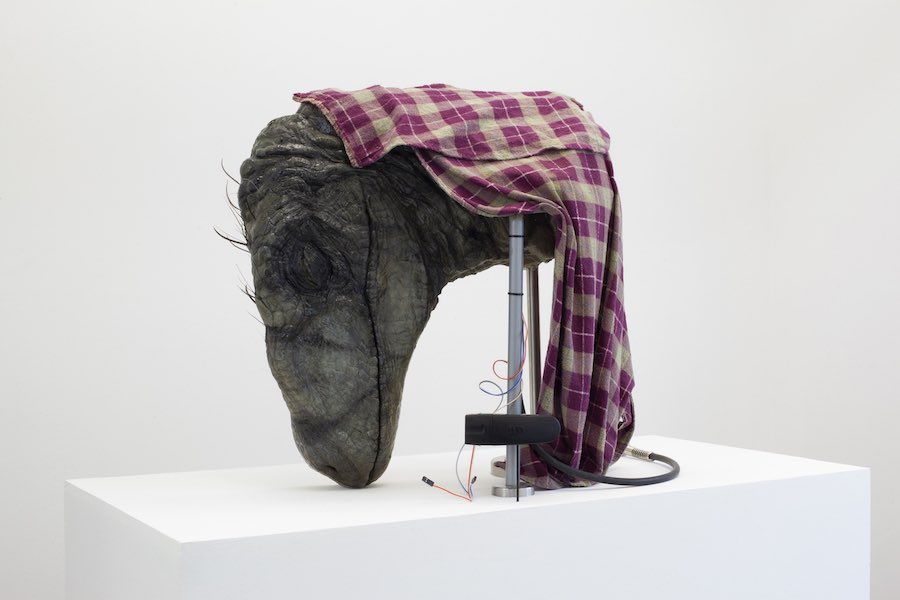

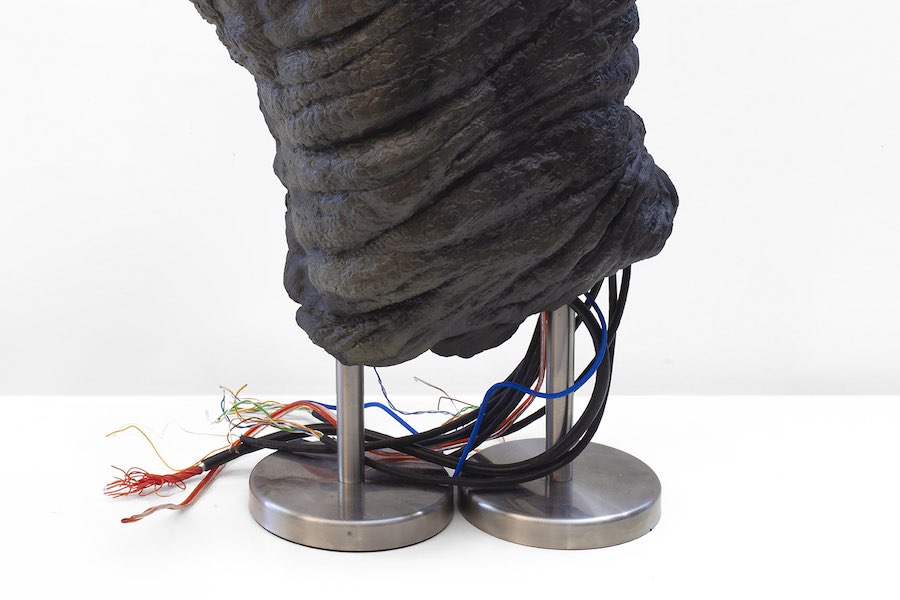

L’opera come dicevo presenta una ovvia e ridondante dicotomia: un lato è figurativo, modellato in resina epossidica bi-componente e dipinto ad olio, l’altro è realizzato con materiali ed oggetti di uso comune, scelti per due ragioni: la capacità di sottolineare tale bidimensionalità, e l’abilità nel suggerirci un immaginario (o più immaginari specifici), decorando la scultura con casuali fregi ornamentali ed astratti.

Il rapporto con lo spettatore è particolarmente importante in questa serie; non viene mostrato, o spettacolarizzato, ma è per me vitale, e mi obbliga a cambiare posizione, a divenire fruitore dell’opera per la seconda volta, ascoltando ed osservando.

Essa considera il pubblico dell’arte di oggi, che è fatto solo in minima parte da persone che avranno la possibilità di vedere le opere dal vivo e in maggior numero da persone che le vedranno, per scelta o necessità, solo attraverso il telefono o il computer. Ne sottolinea la distanza in quanto l’opera se vista in fotografia, vorrebbe facilitare un fraintendimento e suggerire di essere una scultura a tutto tondo nascondendo la sua seconda faccia più astratta o viceversa.

Analizza la difficoltà di ammettere a se stessi e agli altri che le cose non sono come avevamo creduto. Dunque la difficoltà di accettare le cose per ciò che sono, qualora queste in una prima analisi, hanno generato in noi un determinato pensiero.

Ho deciso di utilizzare e di ispirarmi formalmente alle teste degli animatronics di Jurassic Park proprio perché per molte persone della mia generazione è stata una destabilizzante sorpresa sapere che in realtà molti dinosauri erano ricoperti da piume, e quasi per nulla somiglianti a quelle gigantesche lucertole che ci eravamo abituati a sognare e temere. Le opere di questa serie vogliono sottolineare questo particolare sentimento. Questa difficoltà. Questo disagio.

La serie desidera raccontare una riflessione intima e frontale riguardo ad un fraintendimento, ad una difficoltà e alla tendenza dell’essere umano a non voler accettare le cose che si rivelano diverse da ciò che egli aveva sempre creduto.

Non bisognerebbe avere mai paura di cambiare opinione. Lo so, avere una intuizione, anche

solo avere una opinione, aver stigmatizzato una situazione, ci fa sentire molto

intelligenti, ci fa credere di aver capito qualcosa in più di noi stessi

anche, diventa immediatamente identitaria questa opinione e vogliamo anche

somigliare un po’ alle nostre opinioni. Ma non siamo noi a fare del mondo ciò

che vogliamo che sia, solo descrivendolo. È l’arte che osserva noi, ed è lei che ci giudica

attraverso la banalità delle nostre opinioni.

It’s always so hard to admit that things are different than what we had believed at first sight

I decided to talk about one of my most recent works: a series entitled “It’s always so hard to admit that things are different than what we had believed at first sight” because in my opinion, in its simplicity has characteristics emblematic of my work at large.

For many years, my research has attempted to analyze and problematize some specific aspects of art and the art object. I use object in a very broad sense. Often my thoughts start by choosing forms, which are almost always awkward, materials that are fascinating to me because of their hyper- material characteristics, and objects capable of communicating in long-distanced, multi-faceted, and layered manners.

There is a side of my work often returns to reflect on the genealogy of the work itself, investigating themes such as time travel and parallel universes. More and more often, however, the need to deepen these discourses is intertwined with some reflections about the perception of the works by the different types of viewers to which they relate.

I have always been very fascinated by a particular moment in which by observing some works of art the viewer can feel personally involved.

See the work, read the title and feel involved. Feeling involved can upset you for a moment.

When I try to recreate this special empathic bond that links work and spectator and to reconstruct the particular relational dynamic, I try to implement it not through an agreement, or a complicity, but rather through a misunderstanding or a disappointment.

If I had to summarize in one sentence everything my research is about, I would say that it deals with understanding and calculating a distance: the distance between work and viewer, or the distance between it (a work) and its title. The distance that separates the artist from his work and the distance that a work can travel along by continuing to communicate itself. The topic that is dealt with in the piece “It’s always so hard to admit that things are different than what we had believed at first sight” is well described by the phrase that gives it the title.

The need to focus on this concept was born in a completely natural way; often it is people who inspire me more, with their mistakes, their misery and their humanity. In my mind my professional life, my reflections about the language of art, my disappointments, my private life, my own mistakes and those of people I don’t even know, friends of friends, mix together, become one burden of experiences I make my own; that I feel to mine, and as such, all of my work orginates from a sense of necesity and intuition. Formally I let myself be inspired by the things that surround me, by my previous and childish experiences, by my daily life, by what I see every day between traffic lights and road tunnels, by what the algorithms of the different social media I use suggest to me; the shape of things for me is almost always an excuse to emphasize a certain discourse, deepen a process, divert the attention of the public so as to be able to select it, so as to recognize the most attentive and sensitive interlocutors.

In this work two different faces coexist: one suggests three-dimensionality, the other two- dimensionality. They remind us of the only common point between two completely different and almost opposite eras or realities. I give a small example to explain this moment in common, a random example, the first that comes to mind taken from my experience: if I had to define what is the moment that the Triassic and the year 2028 have in common, I would say that it is a rainy day in October 1991. In the morning I had gone to school, and like every morning until my third grade I had tried to escape, with my father waiting for me outside ready to take me back to school and the caretaker chasing me scared. But this happened in the morning. It’s afternoon now. Somewhere in Milan, a special person was born, but I had no idea, I was 8 and I was the absolute center of my universe. I was studying prehistory, and on Italia1(an Italian tv channel) they broadcast Robocop.

That afternoon the Triassic and 2028 occurred simultaneously.

The work as I said presents an obvious and redundant dichotomy: one side is figurative, modeled in two-component epoxy resin and oil painting, the other is made with commonly used materials and objects, selected for two reasons: capacity to emphasize this two-dimensionality, and the ability to suggest an imaginary (or more specific imaginaries), decorating the sculpture with random ornamental and abstract friezes.

The relationship with the viewer is particularly important in this series; it is not shown, or spectacularized, but it is vital for me, and forces me to change position, and leads me to change position, forcing me to become a viewer of this for the second time, by listening and observing. It considers the art viewers of today, which is only minimally made by of people who will have the chance to see the works IRL and in greater numbers by people who will see them, by choice or necessity, only by telephone or computer. It emphasizes the distance from the work, because when viewed in photography, facilitates a misunderstanding, suggests a complete sculpture hiding its second, more abstract and two dimensional face or vice versa. The series wants to be an intimate and frontal reflection about a misunderstanding, a difficulty and the tendency of the human being not to want to accept the things that are different from what he would have always believed.

Analyze the difficulty of admitting to yourself and to others that things are not as we had believed. Therefore the difficulty of accepting things for what they are, if these in a first analysis, have generated a certain thought in us.

I decided to use the dinosaurs and to formally take inspiration from the heads of the Jurassic Park animatronics precisely because for many people of my generation it was a destabilizing surprise to know that in reality many dinosaurs were covered with feathers, and almost not at all like those gigantic lizards that in our imagination we used to dream and fear.

The works in this series want to emphasize this particular feeling. This difficulty. This discomfort.

You should never be afraid to change your mind. I know, having an intuition, even having an opinion, stigmatizing a situation, makes us feel very intelligent, makes us believe that we have understood something more about ourselves too, this opinion immediately becomes an aspect of our identity and we also want to look a bit like to our opinions. But we are not the ones who make the world what we want it to be, just by describing it.

Per leggere gli altri interventi di I (never) explain

I (never) explain – ideato da Elena Bordignon – è uno spazio che ATPdiary dedica ai racconti più o meno lunghi degli artisti e nasce con l’intento di chiedere loro di scegliere una sola opera – recente o molto indietro del tempo – da raccontare. Una rubrica pensata per dare risalto a tutti gli aspetti di un singolo lavoro, dalla sua origine al processo creativo, alla sua realizzazione.