English version below —

C’è una luce che gira come un respiro, un faro immerso nel sangue e nel sudore.

In King of Boys (Abattoir of Makoko) (2015), il film che apre cronologicamente questo percorso, una bottiglia di plastica rossa riciclata — una membrana povera, improvvisata — tinge il mattatoio di Makoko di una febbre cromatica, trasformando la visione in una condizione percettiva. Per un istante, il mondo appare filtrato dall’interno del corpo, come se la camera stessa respirasse sangue e calore. Non è un documentario: è un corpo che guarda altri corpi. La cinepresa si muove come un organo interno, un battito che si confonde con quello degli uomini.

È da questa luce, da questa vibrazione sanguigna che Tendered, la personale di Karimah Ashadu al Camden Art Centre, prende avvio. Come un lungo respiro che si prolunga, si deposita sui muri, attraversa la pelle di chi guarda. Una luce che non mostra, ma diviene materia di ascolto. Una luce che non rivela, ma accompagna: non mette a fuoco, si lascia avvolgere. La curatela di Alessandro Rabottini e Leonardo Bigazzi — sviluppata all’interno della visione di Fondazione In Between Art Film, che da anni indaga la soglia porosa tra cinema, installazione e performance orienta l’intero percorso espositivo. Non come un apparato esterno, ma come un’architettura di sensibilità.

È da qui che comincia la narrazione, in un intreccio di vicinanze e di distanze, di intimità e lavoro, di fragilità e necessità. Nulla, in questa mostra, si offre come semplice contenuto da osservare: tutto si manifesta come relazione viva.

Karimah Ashadu nasce a Londra nel 1985, cresce tra Regno Unito e Nigeria, porta nella propria formazione due traiettorie che non si risolvono mai l’una nell’altra. La sua vita si muove tra Amburgo e Lagos, tra Europa e Africa, tra ordine e frattura, tra istituzioni e strade.

È questa mobilità – geografica, culturale, affettiva – a modellare il suo sguardo.

Prima di dedicarsi al cinema, studia pittura: e nella pittura apprende la densità del colore, il suo spessore, la sua forza d’urto, il suo potere di trasformare un punto in un ritmo.

Ogni film porta traccia di questo apprendistato: la cinepresa non descrive il mondo, lo tatua.

Lo stria di vibrazioni, lo sfiora, gli cede la pelle.

È importante ricordare che la pratica di Ashadu non si è mai sviluppata come un percorso di pura osservazione. Fin dagli inizi, quando sperimentava con piccole cineprese e materiali di fortuna, la sua attenzione non era rivolta tanto all’immagine quanto alla relazione che l’immagine instaurava. Non si chiedeva: “Che cosa posso mostrare?”, ma piuttosto: “Che cosa posso attraversare senza spezzarlo?”. Questa differenza, apparentemente sottile, definisce in profondità il suo modo di lavorare. Anche quando filma ambienti duri, spazi saturi di violenza quotidiana, Ashadu non cerca il trauma come spettacolo, né il realismo come prova. Cerca una zona intermedia in cui il mondo possa apparire senza essere catturato, e il corpo possa mostrarsi senza essere esposto.

È in questa zona che maturano i tratti più caratteristici del suo cinema: l’assenza di giudizio, la sospensione del commento, la scelta di lasciare che siano i corpi – non le parole – a definire la geometria del quadro. Ogni film sembra partire da un atto di fiducia: fiducia che il luogo filmato sappia dire se stesso, fiducia che l’inquadratura possa trovare il proprio limite senza imporlo, fiducia che l’incontro tra chi filma e chi viene filmato generi una forma di conoscenza non concettuale ma sensoriale.

È in questo senso che le parole di Ashadu assumono un peso quasi programmatico: “I just watch people all the time, often in quite intense ways” (Plaster Magazine, 16 maggio 2025).

Guardare, per lei, non è un gesto neutro: è un’esposizione reciproca, un atto che mette in gioco la vulnerabilità di entrambi i lati dell’immagine.

Ed è forse in questo senso che Ashadu va oltre il “documentario”: non perché rifiuti la realtà, ma perché la tratta come un organismo complesso, dotato di una sua intensità, di una sua ciclicità respiratoria, di un suo ritmo. Non c’è un “messaggio” da decifrare, non c’è una tesi estetica o politica da sostenere. C’è la comprensione – lenta, profonda – che ogni corpo porta con sé una costellazione di forze, e che il cinema può solo tentare di accompagnarle per un tratto, senza possederle mai.

Anche se questa è una successione solo cronologica e non espositiva, dopo la ferita cromatica e tattile di King of Boys, Cowboy (2022) si offre come un intervallo di grazia. Non un sollievo, ma una sospensione. Un uomo cammina accanto al suo cavallo su una distesa d’acqua e sabbia: non c’è eroismo, non c’è posa, solo un passo condiviso, una forma di complicità elementare. In un luogo dove il mare porta con sé la memoria della storia africana – partenze forzate, ritorni impossibili, orizzonti che feriscono – Ashadu non cerca il trauma: cerca il fiato. Il cavallo non è un simbolo ma un corpo che accompagna un altro corpo, un modo di attraversare il mondo. Il film suggerisce che la mascolinità può essere, almeno per un momento, un gesto di cura, un equilibrio provvisorio con la terra e con l’animale. È un respiro lento tra due densità, una parentesi di fiducia che non cancella la fatica ma la riconfigura.

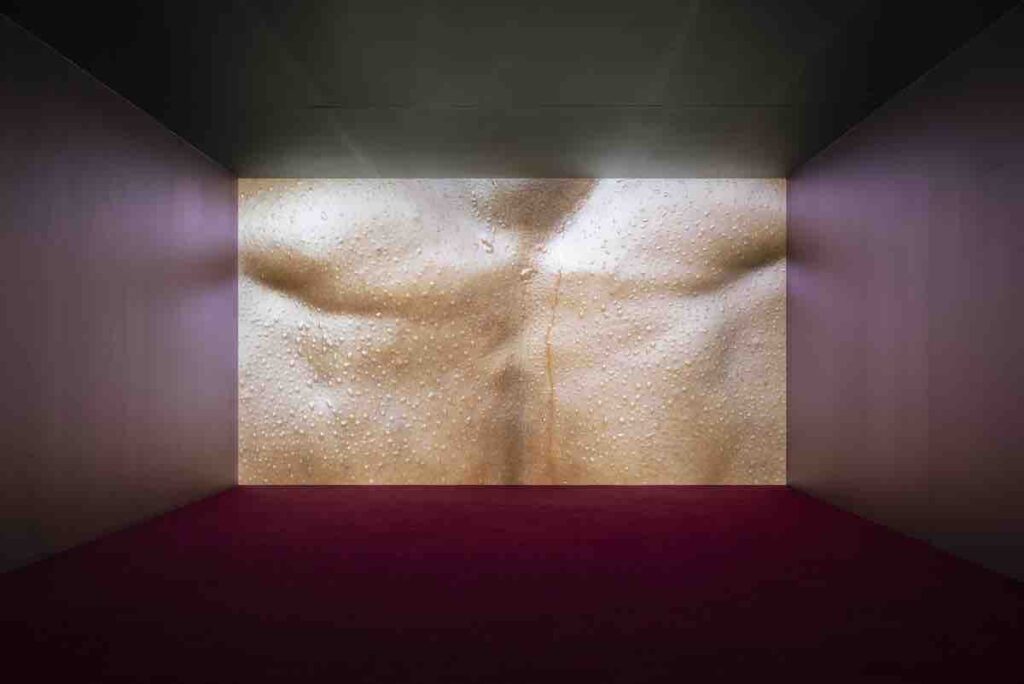

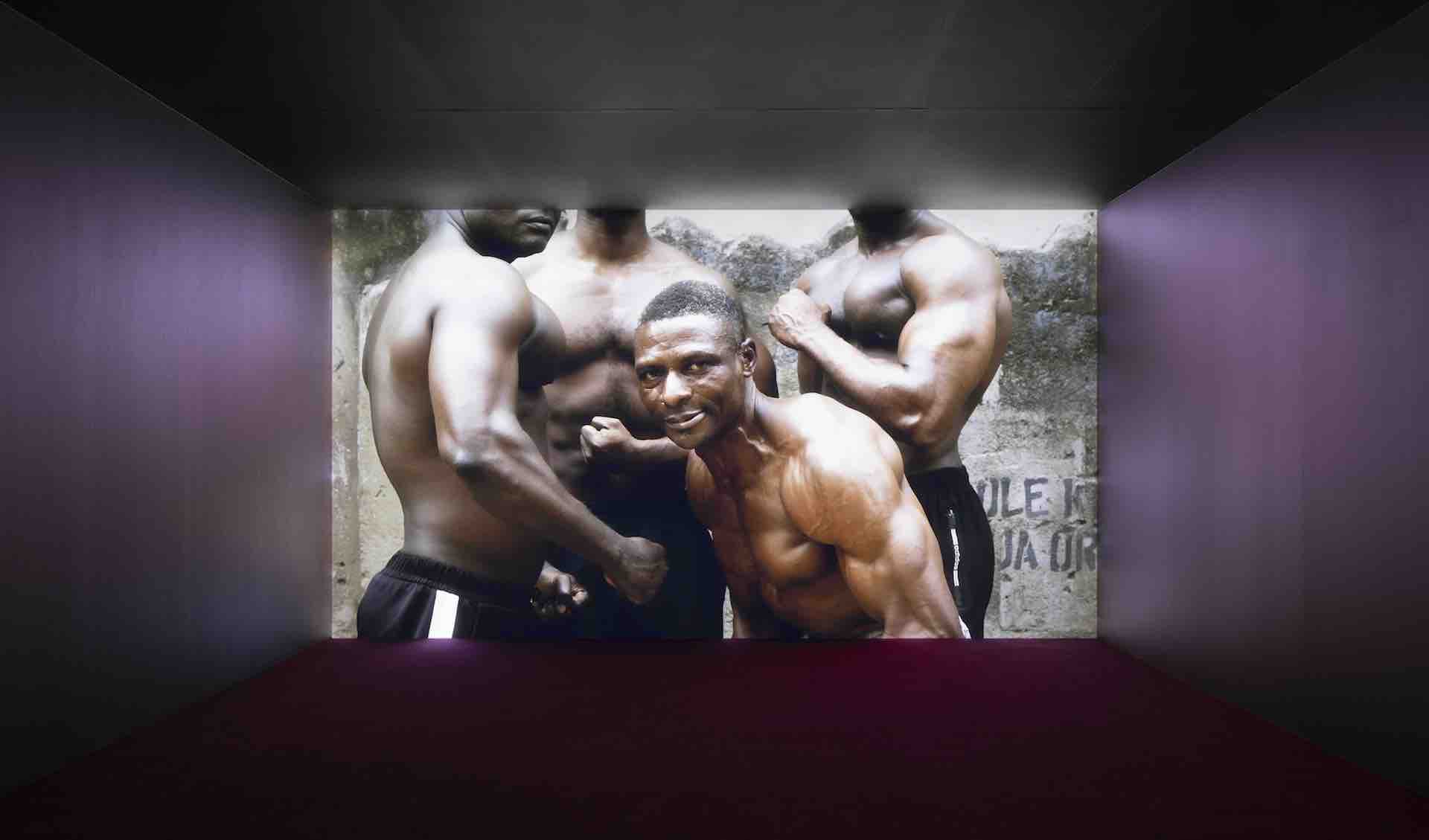

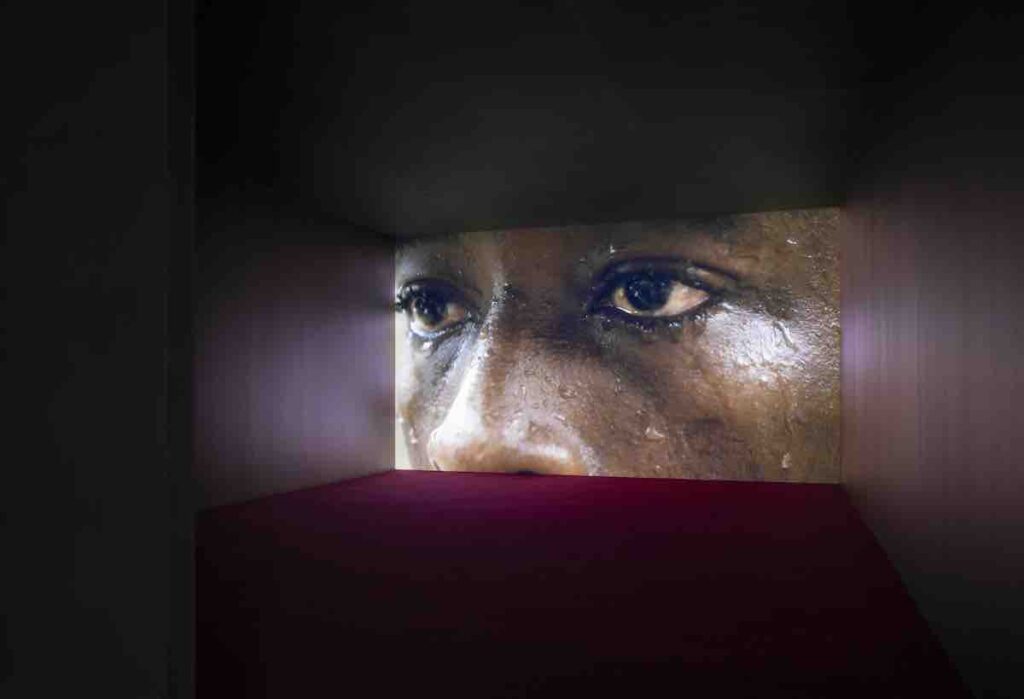

Nel 2024 Ashadu riceve il Leone d’Argento alla Biennale di Venezia per il film Machine Boys, un lavoro che indaga il desiderio di autonomia dei motociclisti di Lagos, e insieme il loro essere sospesi in una città che non concede stabilità. Con Machine Boys, Ashadu attraversa un altro corpo collettivo: quello degli okada, i motociclisti che tagliano la città come vene aperte, in un’economia informale che non conosce tregua. Li segue nel loro movimento continuo – accelerazioni, deviazioni, arresti improvvisi – lasciando che siano i loro gesti a costruire il ritmo del film: mani che stringono manubri, motori riparati sulla polvere, strade che si aprono e si richiudono come un fiato trattenuto. Non c’è eroismo né vittimismo: c’è la dignità instabile di chi vive ai margini della legge ma al centro di una tensione vitale. Il rombo dei motori, il vento, le voci si intrecciano in una tessitura sonora che non accompagna l’immagine: la precede, la incide. Machine Boys è una meditazione sul rischio come forma di vita, sull’autonomia come miraggio e necessità, su corpi che avanzano perché indietro non c’è più nulla. Pur non essendo presente in mostra, Machine Boys svolge qui una funzione essenziale: è il ponte che permette di comprendere il modo in cui Ashadu osserva, ascolta e restituisce la vitalità urbana di Lagos, e chiarisce poi la logica interna della triade di film esposti. È da questa soglia laterale che si comprende la sequenza che struttura la mostra — King of Boys (Abattoir of Makoko), Cowboy e MUSCLE — un arco visivo che attraversa il lavoro, la vulnerabilità, la forza e le forme mobili dell’autodefinizione.Come se il film, rimasto fuori dallo spazio espositivo, ne illuminasse comunque il respiro: una soglia che prepara il terreno, un controcanto necessario. Dopo la quiete di Cowboy e il rischio evocato da Machine Boys, la sequenza procede con MUSCLE (2025), il film che chiude idealmente la triade esposta e che ne rovescia l’atmosfera. Se Cowboy era passo e fiato, questo terzo movimento è tensione e compressione. Nessun protagonista, nessuna linearità: solo corpi che lottano per definire se stessi. La palestra all’aperto negli slums di Lagos è uno spazio minimo, sovraccarico, costruito con materiali di fortuna. La cinepresa sfiora i corpi fino a dissolvere il loro contorno: i muscoli gonfiati, le vene sporgenti, la pelle lucida di sudore riempiono lo schermo, trasformando la forza in un’immagine vulnerabile. È una prossimità così radicale che, a tratti, le figure diventano astrazione, mutano in forma, luce, materia, come se il corpo fosse uno spazio da attraversare più che un soggetto da fissare.

La scarsa profondità di campo comprime l’azione; i corpi si sovrappongono; la visibilità diventa disciplina. Il clangore del ferro, i respiri gutturali, i rumori della strada compongono una coreografia sonora sincopata. Il gesto del “pure water”, inquadrato con precisione quasi rituale, rivela una grammatica di classe e un capitalismo minimo. In questo dettaglio – trattenuto e calibrato come un “product placement” involontario – si intuisce la trama invisibile di un’economia che attraversa ogni corpo, ogni gesto.

Qui la mascolinità non è mai un dato: è una performance fragile, oscillante, bisognosa di testimoni. Un’imbricazione di gesto, tono, attivazione e percezione che rende ogni movimento un esercizio di visibilità, un tentativo di essere riconosciuti senza essere ridotti a una forma unica o fissa. Nei corpi di MUSCLE la forza non è potere: è una negoziazione instabile tra resistenza ed esposizione. Achille Mbembe, riflettendo sul postcoloniale, ricorda che la vita è una negoziazione continua tra ferita e possibilità. (Politiques de l’inimitié, 2016). Nei corpi di MUSCLE questa negoziazione è visibile, palpabile, quasi dolorosa: sono corpi di bodybuilders, cesellati dalla disciplina, ma attraversati da una vulnerabilità che li spoglia della loro ostentata forza.

Nel film, il suono è una forza autonoma. Il ferro che sbatte, il ritmo dei pesi, la plastica dei sacchetti che si strappa per versare acqua sui corpi: tutto crea una tessitura acustica che non accompagna l’immagine, ma la precede. Tina Campt, in Listening to Images (2017), sostiene che ci sono immagini che è necessario ascoltare prima di poterle vedere. I film di Ashadu appartengono esattamente a questa categoria: non si capiscono con la mente, ma con il corpo. Prima il rumore, poi la luce. Prima il ritmo, poi la visione.

E così, mentre gli uomini scolpiscono e ritualizzano i propri corpi, lo spettatore intravede il loro desiderio che prende forma: una zona immateriale dell’affetto, dell’attesa, dell’ambizione, che vibra dentro ogni gesto e non si lascia mai del tutto nominare.Forse il punto più radicale dell’opera di Ashadu non è la rappresentazione del lavoro o della mascolinità, ma la costruzione di uno spazio di prossimità che non diventa mai appropriazione. Nei suoi film, la camera non si avvicina per possedere: si avvicina per esitare, per attendere la temperatura dell’altro. Questa esitazione è il contrario esatto dello sguardo documentario che pretende di “sapere”: è una forma di sospensione, un margine in cui l’immagine non si offre come spiegazione ma come possibilità condivisa.

In questo senso, Lagos non è mai, nei suoi film, un semplice contesto urbano. È un organismo che precede e condiziona ogni gesto. Una città che non si lascia stabilizzare da una forma, sempre sul punto di frantumarsi e ricomporsi. Lagos è vibrazione, sospensione, spinta centrifuga: una geografia della sopravvivenza che imprime nei corpi una postura particolare, una sollecitazione costante.

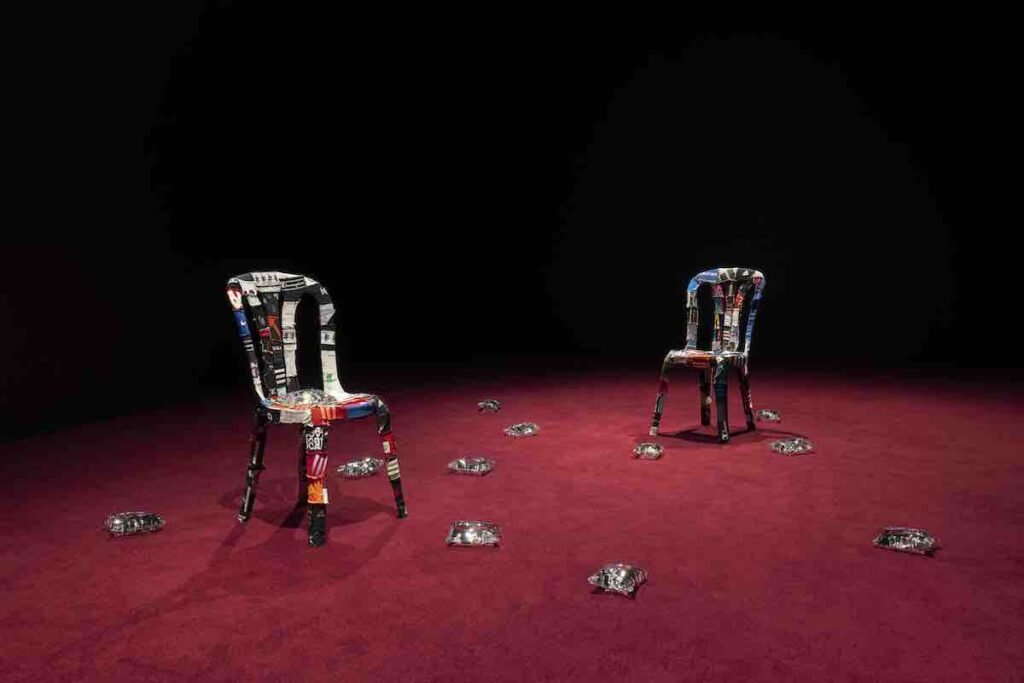

Le sculture presenti in mostra – strutture in ferro, corde annodate, frammenti di plastica, oggetti che sembrano usciti direttamente dalla palestra all’aperto – non sono semplici complementi. Sono prolungamenti materiali del film, resti che non documentano ma incarnano.

E poi il ritorno al silenzio: non un silenzio pacificato, ma il silenzio di chi ha attraversato tre stati del corpo – la ferita di King of Boys, il fiato di Cowboy, la tensione di MUSCLE – e ora porta sulla pelle la memoria di ciascuno.

Quando il percorso si chiude e la sala torna al buio, resta un’impressione che non è mentale, ma fisiologica. È come se il corpo dello spettatore si fosse lasciato attraversare dal ritmo dei film, come se qualcosa fosse rimasto sotto pelle: una pulsazione. Una tremula memoria del lavoro, del respiro, del passo. Una luce che non vuole spiegare nulla, ma che insiste nel suo movimento circolare. Una luce che non rivela: ascolta. Una luce che non pretende: resta.

Cover. Installation view of MUSCLE (2025) in Karimah Ashadu, Tendered at Camden Art Centre, 2025. Courtesy the artist and Fondazione In Between Art Film. (c) Andrea Rossetti

Karimah Ashadu. Tenderness as Resistance

Text by Rita Selvaggio —

There is a light that circles like a breath, a beacon immersed in blood and sweat.

In King of Boys (Abattoir of Makoko) (2015), the film that opens this trajectory in chronological terms, a recycled red plastic bottle — a poor, improvised membrane — stains the Makoko slaughterhouse with a chromatic fever, transforming vision into a perceptual condition. For an instant, the world appears filtered from inside the body, as if the camera itself were inhaling blood and heat. This is not a documentary: it is a body looking at other bodies. The camera moves like an internal organ, a pulse merging with the pulse of the men around it.

It is from this light, from this sanguine vibration, that Tendered, Karimah Ashadu’s solo exhibition at Camden Art Centre, begins. Like a long breath held and released, it settles on the walls, crosses the viewer’s skin. A light that does not show but becomes a substance of listening. A light that does not reveal but accompanies: it does not seek focus; it allows itself to be enveloped. The curatorship of Alessandro Rabottini and Leonardo Bigazzi — shaped within the vision of Fondazione In Between Art Film, which has long explored the porous threshold between cinema, installation and performance — guides the entire exhibition. Not as an external framework, but as an architecture of sensibility.”

The narrative begins here, in an interweaving of proximities and distances, of intimacy and labour, of fragility and necessity. Nothing in this exhibition presents itself as a simple object to be observed: everything manifests as a living relation.

Karimah Ashadu was born in London in 1985 and grew up between the United Kingdom and Nigeria, carrying within her background two trajectories that never fully resolve into one another. Her life moves between Hamburg and Lagos, between Europe and Africa, between order and fracture, between institutions and the street.

It is this mobility — geographical, cultural, affective — that shapes her gaze.

Before turning to film, she studied painting; and in painting she learned the density of colour, its thickness, its impact, its power to turn a single point into a rhythm.

Every film bears the trace of this apprenticeship: the camera does not describe the world, it tattoos it.

It scores it with vibrations, brushes against it, yields its own skin to it.

It is important to remember that Ashadu’s practice has never developed as a path of pure observation. From the very beginning, when she was experimenting with small cameras and makeshift materials, her attention was not directed toward the image itself but toward the relationship the image could establish. She did not ask: “What can I show?” but rather: “What can I move through without breaking it?” This difference, seemingly subtle, defines her working method in depth. Even when she films harsh environments, spaces saturated with everyday violence, Ashadu does not seek trauma as spectacle, nor realism as proof. She searches for an intermediate zone where the world may appear without being captured, and the body may reveal itself without being exposed. It is within this zone that the most characteristic traits of her cinema take shape: the absence of judgment, the suspension of commentary, the choice to let bodies — not words — define the geometry of the frame. Every film seems to begin with an act of trust: trust that the place filmed knows how to speak for itself; trust that the framing will find its own limit without imposing one; trust that the encounter between the one who films and the one being filmed can generate a form of knowledge that is not conceptual but sensorial. It is in this sense that Ashadu’s own words take on an almost programmatic weight: “I just watch people all the time, often in quite intense ways” (Plaster Magazine, 16 May 2025).

Looking, for her, is not a neutral gesture: it is a form of reciprocal exposure, an act that places the vulnerability of both sides of the image at risk.

And perhaps it is in this sense that Ashadu moves beyond “documentary”: not because she rejects reality, but because she treats it as a complex organism, endowed with its own intensity, its own respiratory cycles, its own rhythm. There is no “message” to decode, no aesthetic or political thesis to advance. What there is — slowly, deeply — is the understanding that every body carries within it a constellation of forces, and that film can only attempt to accompany them for a brief stretch, never to possess them.

Although this is a merely chronological — not an exhibition sequence, after the chromatic and tactile wound of King of Boys, Cowboy (2022) offers itself as an interval of grace. Not a relief, but a suspension. A man walks beside his horse across a stretch of water and sand: there is no heroism, no pose, only a shared step, a form of elemental companionship. In a place where the sea carries the memory of African history — forced departures, impossible returns, horizons that cut — Ashadu does not seek trauma: she seeks breath. The horse is not a symbol but a body accompanying another body, a way of moving through the world. The film suggests that masculinity may be, at least for a moment, an act of care, a provisional equilibrium with the land and with the animal. It is a slow breath between two densities, a parenthesis of trust that does not erase fatigue but reconfigures it.

In 2024, Ashadu received the Silver Lion at the Venice Biennale for Machine Boys, a work that investigates the desire for autonomy among Lagos motorcyclists, while also revealing their suspension within a city that grants no stability. With Machine Boys, Ashadu traverses another collective body: that of the okada, the riders who cut across the city like open veins, operating within an informal economy that knows no pause. She follows them in their continuous movement — accelerations, swerves, abrupt halts — allowing their gestures to construct the film’s rhythm: hands gripping handlebars, engines repaired on dusty ground, roads that open and close like a held breath. There is neither heroism nor victimhood: only the unstable dignity of those who live at the margins of the law yet at the centre of a vital tension. The roar of engines, the wind, the voices merge into a sonic weave that does not accompany the image: it precedes it, inscribes it.

Machine Boys is a meditation on risk as a mode of life, on autonomy as both mirage and necessity, on bodies that move forward because behind them nothing remains. Although not present in the exhibition, Machine Boys plays an essential function here: it is the bridge through which one can understand how Ashadu observes, listens to, and renders the urban vitality of Lagos — and it clarifies the internal logic of the triad of films on view. It is from this lateral threshold that the sequence structuring the exhibition becomes legible — King of Boys (Abattoir of Makoko), Cowboy, and MUSCLE — a visual arc that moves through labour, vulnerability, strength, and the shifting forms of self-definition. As if the film, kept outside the exhibition space, nonetheless illuminated its breath: a threshold that prepares the ground, a necessary counterpoint.

After the quiet of Cowboy and the risk evoked by Machine Boys, the sequence advances with MUSCLE (2025), the film that ideally closes the exhibited triad and overturns its atmosphere. If Cowboy was step and breath, this third movement is tension and compression. No protagonists, no linearity: only bodies struggling to define themselves.

The open-air gym in the Lagos slums is a minimal, overloaded space, built from improvised materials. The camera brushes the bodies until dissolving their contours: swollen muscles, protruding veins, sweat-glossed skin fill the screen, turning strength into a vulnerable image. It is a proximity so radical that, at times, the figures become abstraction, shifting into form, light, matter — as if the body were a space to be moved through rather than a subject to be fixed.

The shallow depth of field compresses action; bodies overlap; visibility becomes discipline. The clang of metal, the guttural breaths, the street noise compose a syncopated sonic choreography. The “pure water” gesture, framed with an almost ritual precision, reveals a grammar of class and a minimal capitalism. In this detail — held and calibrated like an involuntary “product placement” — one intuits the invisible mesh of an economy passing through every body, every gesture.

Here, masculinity is never a given: it is a fragile performance, oscillating, in need of witnesses. An interlocking of gesture, tone, activation, and perception that renders each movement an exercise in visibility, an attempt to be recognised without being reduced to a single, fixed form. In the bodies of MUSCLE, strength is not power: it is an unstable negotiation between resistance and exposure. Achille Mbembe, reflecting on the postcolonial, reminds us that life is a continuous negotiation between wound and possibility (Politiques de l’inimitié, 2016).

In the bodies of MUSCLE, this negotiation is visible, palpable, almost painful: they are the bodies of bodybuilders, chiselled by discipline yet traversed by a vulnerability that strips them of their ostentatious force.

In the film, sound is an autonomous force. Metal striking metal, the rhythm of weights, the plastic of sachets tearing open to pour water over bodies: everything forms an acoustic weave that does not accompany the image, but precedes it. Tina Campt, in Listening to Images (2017), argues that there are images that must be listened to before they can be seen. Ashadu’s films belong precisely to this category: they are not grasped by the mind but by the body. First the noise, then the light. First the rhythm, then the vision.

And so, while the men sculpt and ritualise their bodies, the viewer glimpses the desire taking shape within them: an immaterial zone of affect, anticipation, ambition, vibrating in every gesture and never fully nameable. Perhaps the most radical point of Ashadu’s work is not the representation of labour or masculinity, but the construction of a space of proximity that never becomes appropriation. In her films, the camera does not move close in order to possess; it moves close in order to hesitate, to wait for the other’s temperature. This hesitation is the exact opposite of the documentary gaze that claims to “know”: it is a form of suspension, a margin in which the image does not present itself as an explanation but as a shared possibility.

In this sense, Lagos is never simply an urban backdrop. It is an organism that precedes and conditions every gesture. A city that refuses to stabilise into a form, always on the verge of breaking apart and recomposing itself. Lagos is vibration, suspension, centrifugal force: a geography of survival that imprints on bodies a particular posture, a constant solicitation.

The sculptures in the exhibition — iron structures, knotted ropes, fragments of plastic, objects that seem to emerge directly from the open-air gym — are not mere complements. They are material extensions of the film, remnants that do not document but embody.

And then comes the return to silence: not a pacified silence, but the silence of someone who has passed through three states of the body — the wound of King of Boys, the breath of Cowboy, the tension of MUSCLE — and now carries on the skin the memory of each.

When the path comes to an end and the room returns to darkness, what remains is an impression that is not mental but physiological. It is as if the viewer’s body had allowed itself to be crossed by the rhythm of the films, as if something had remained beneath the skin: a pulse. A trembling memory of labour, of breath, of step. A light that does not seek to explain, but insists in its circular movement. A light that does not reveal: it listens.

A light that does not claim: it stays.