English version below

Patriarchy is History è la terza personale di Yael Bartana ospitata alla galleria Raffaella Cortese di Milano. Viste le restrizioni in atto, la mostra è visitabile solo per appuntamento (tel. 02 2043555 – in via A. Stradella 7-1- 4).

In occasione della mostra Mauro Zanchi e Sara Benaglia hanno posto alcune domande all’artista.

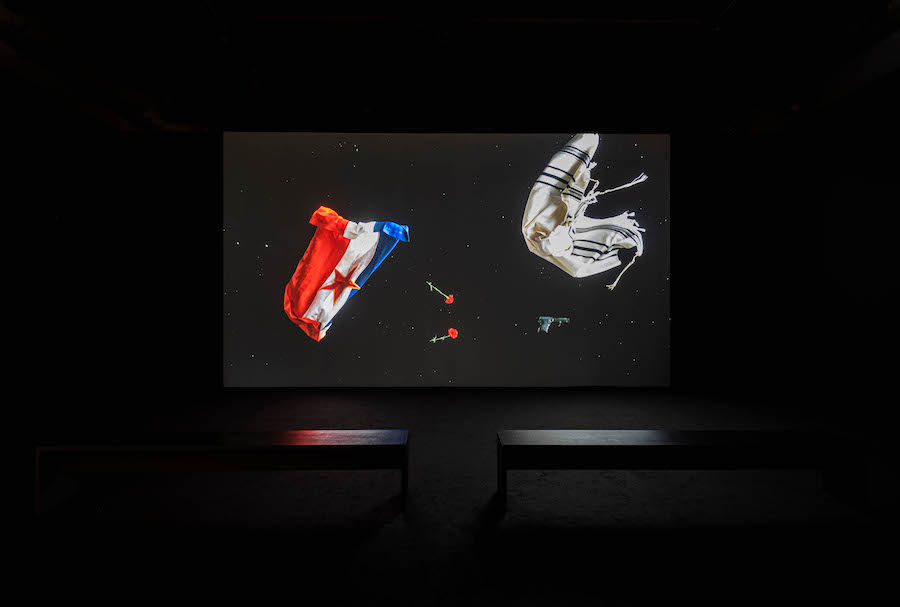

Mauro Zanchi e Sara Benaglia: Nella recente mostra Cast Off (2019), allestita alla Fondazione Modena Arti Visive nella sede di Palazzo Santa Margherita, siamo rimasti colpiti dal video in slow-motion, Tashlikh (Cast Off), dove piovono oggetti, simboli dei genocidi, delle torture, delle atrocità perpetrate in guerre vicine e lontane, della nostra società, che possono appartenere sia ai carnefici sia alle vittime di persecuzioni etniche e delle guerre. Stivaloni neri, medaglie al valore militare, vestiti, maschere africane, oggetti di diverse religioni cadono a pioggia sopra le nostre teste. Quale è la via da intraprendere, giorno dopo giorno, per opporsi all’anestesia, all’indifferenza, all’omertà, all’istintivo balzo di lato per non essere colpiti dagli oggetti che cadono dal cielo (nel suo video)?

Yael Bartana: Credo che un’opera d’arte, quando funziona, ci ricordi che la vita è complessa, multisfaccettata, contraddittoria e sorprendente. Quando è ben fatta, ci pone nuovi interrogativi da contemplare, discutere, approfondire. Dovrebbe invitarci a esplorare nuovi territori, non solo in senso pratico ma anche figurativo. Quindi, alla fine, non si tratta di dare indicazioni pragmatiche su come vivere la vita o essere politicamente attivi, ma di rivelare e mettere in discussione meccanismi che fanno parte della nostra realtà.

MB / SB: Cosa significa per Lei il senso di appartenenza a una patria, partecipare a una comunità? Che valore hanno nel suo lavoro i concetti di “identità” e “rito”?

YB: L’immaginazione politica è il fulcro centrale nella mia pratica artistica, soprattutto in relazione al mio passato e al modo in cui affronto i concetti di identità e rituali. Per molti anni ho esplorato le due nozioni, simulando alcune situazioni e combinando finzione e realtà in modi differenti. Quando ho lavorato a Polish Trilogy (2012), per esempio, ero interessata a invertire le narrazioni storiche e a introdurre uno scenario fantasioso e da copione, come modo per commentare la realtà attuale, e sfidare alcune narrazioni tradizionali nazionali e storiche. Queste si basano esattamente sulla nostra comprensione dell’identità e sui rituali nazionali. Trovo quindi che queste due componenti – la creazione di una certa ambientazione o di un certo evento e la sua documentazione – siano estremamente interessanti e importanti.

MB / SB: Può parlarci delle idee alla base della sua mostra Patriarchy is History (2020)?

YB: I lavori in mostra, dal video The Undertaker alla serie fotografica fino agli oggetti, hanno come punti di partenza le mie due performance What If Women Ruled the World (2017-2018) e Bury Our Weapons, Not Our Bodies! (2018). Tutto[sb1] è iniziato dopo che il Philadelphia Museum of Art ha acquisito la Polish Trilogy intitolata And Europe will be Stunned, con l’intenzione di allestire la trilogia video nel museo, e allo stesso tempo mi ha invitato a lavorare su una nuova commissione. Ho proposto al museo di realizzare una sorta di azione – “a staged protest” – nel contesto del Secondo Emendamento degli Stati Uniti – quello che dà agli americani il diritto di portare armi – che io ho invece sostituito con il diritto di seppellire le armi. Il contesto storico di Philadelphia è molto specifico, ma naturalmente il lavoro tratta del seppellimento della violenza. Ho pensato a questo lavoro come parte di un’azione che sarei felice di vedere accadere in Israele; mi piacerebbe molto se gli israeliani seppellissero le loro armi. Fa proprio parte dell’etica israeliana: avere forza, avere una forza militare.

MB / SB: Nelle opere video – nella mostra Cast Off a Modena – agisce la mescolanza fra uno stile documentaristico e una modalità di ripresa, tratta da film di propaganda sionista degli anni Venti e Trenta, dove compaiono momenti che possono risultare quasi ironici. Che ruolo ha l’ambiguità all’interno di questi suoi lavori, che stanno al confine fra realtà e finzione?

YB: L’ambiguità è sempre stata un elemento importante del mio lavoro. Jacques Rancière osserva che la realtà debba essere romanzata per poter essere pensata, e mi piacerebbe pensare a questo come un punto di partenza per la mia pratica artistica. Come dite, i miei film non sono veramente documentari, almeno non documentari secondo una definizione convenzionale. Il mio interesse per il documentario sta nello spazio tra il reale e la finzione. Quando giro un nuovo film, cerco spesso quei momenti documentativi e autentici che accadono sulla strada durante le riprese di una scena e mi interessa includerli nell’editing. Ciò che sta al centro della mia pratica è la documentazione della realtà fittizia, che creo sulla base del nostro mondo e della vita quotidiana. Mi piace esplorare ciò che accade quando si colloca un elemento fittizio all’interno della realtà, cosa fa al nostro mondo reale, come sfida le condizioni reali date e come provoca il pubblico.

MB / SB: Facendo riferimento al progetto interdisciplinare in corso What if Women Ruled the World? (2017-2018) vorremmo chiederle che cosa pensa del rapporto tra femminismo e pace? Come ha sviluppato una risposta attraverso il cast di questo lavoro? Stiamo pensando anche a un contesto specifico, che è l’articolo di Dilar Dirik Femminismo pacifismo o passivo-ismo? Pubblicato su Open Democracy

YB: Più di ogni altra cosa, What if Women Ruled the World è un esperimento. Il titolo stesso suggerisce che il progetto non cerca di fare un’affermazione del tipo: “il mondo sarebbe stato un posto migliore (o peggiore) se le donne lo avessero governato”. La domanda su cosa sarebbe successo se le donne avessero governato il mondo mi è venuta in mente qualche anno fa, quando pensavo allo status quo del conflitto israelo-palestinese. Dopo aver vissuto per anni una realtà così frustrante, ho iniziato a immaginare cosa sarebbe potuto succedere se le donne avessero governato la situazione politica sia in Israele sia in Palestina. Il conflitto sarebbe stato risolto? La realtà sarebbe stata diversa? Naturalmente non stiamo parlando di mantenere le stesse strutture e di cambiare il sesso delle persone al vertice; questo probabilmente non cambierebbe nulla. Stiamo parlando qui dei meccanismi esistenti che governano il nostro mondo, che sono stati storicamente sviluppati da uomini al potere. E naturalmente, pensare a questa domanda nel contesto israelo-palestinese mi ha fatto riflettere in un senso più ampio: e se le donne governassero il mondo intero? In questa accezione, il progetto mira a mettere in discussione tutto ciò che sappiamo sulle strutture politiche. Sono abbastanza sicura che se avessi avuto una risposta a questa domanda probabilmente non avrei lavorato a un progetto del genere.

Tuttavia è importante ricordare che, parallelamente agli sforzi artistici globali nel reagire alla folle realtà in cui viviamo, assistiamo in tutto il mondo ad alcuni eventi politici e sociali che ci ricordano che stiamo percorrendo la strada giusta. Cinque giovani donne sono ora a capo della leadership in Finlandia; la protesta per il cambiamento climatico è guidata da giovani provenienti da ogni angolo del pianeta; c’è poi l’intera vicenda #metoo e il fatto che Harvey Weinstein sia stato condannato, un caso simbolico che manda un chiaro segnale: tutto ciò ha un impatto notevole sia a livello pragmatico, sia a uno più profondo e psicologico, influenza la nostra mente, la nostra percezione di ciò che è possibile e di quali siano i limiti. Non solo per noi stessi, ma soprattutto per le prossime generazioni che dovranno prendersi cura della nostra terra.

Interview with Yael Bartana

By Mauro Zanchi and Sara Benaglia

Mauro Zanchi and Sara Benaglia: In the recent exhibition “Cast Off”, set up in Palazzo Santa Margherita in Modena, we were struck by the slow-motion video “Tashlikh (Cast Off)”, where objects, symbols of genocide, torture, atrocities perpetrated in wars near and far – which may belong both to the executioners and to the victims of ethnic persecution and wars -, rain down. Black boots, military valour medals, clothes, African masks, objects of different religions drop down over our heads. Which is the way to take, day after day, to oppose anesthesia, indifference, conspiracy of silence, so as not to be struck by the objects falling from the sky (in your video)?

Yael Bartana: I believe that a work of art, when at its best, reminds us that life is complex, multi-faceted, contradictory and surprising. When done well, it poses new questions for us to contemplate, discuss, dive deeper into. It should invite us to explore new territory, not only practically but also figuratively. So, in the end we are not really talking here about giving pragmatic directions as to how to live life or be politically active, but about revealing and putting in question mechanisms that are part of our reality.

MZ / SB: What does the sense of belonging to a homeland and participating in a community mean to you? What value do the concepts of “identity” and “ritual” have in your work?

YB: Political imagination is very central to my artistic practice, especially in relation to my own past and how I deal with these two concepts of identity and rituals. For many years now, I’ve been exploring the two by simulating certain situations and combining fiction and reality in different ways. When working on the Polish trilogy, for example, I was interested in reversing historical narratives and introducing an imaginative, scripted scenario as a way to comment on the present reality, and challenge some traditional national and historical narratives. All these use and are based exactly on our understanding of identity as well as on national rituals. So, I find these two components, the creation of a certain setting or event and the documentation of it, extremely interesting and important.

MZ / SB: Please can you tell us about the ideas behind your show Patriarchy is History (2020)?

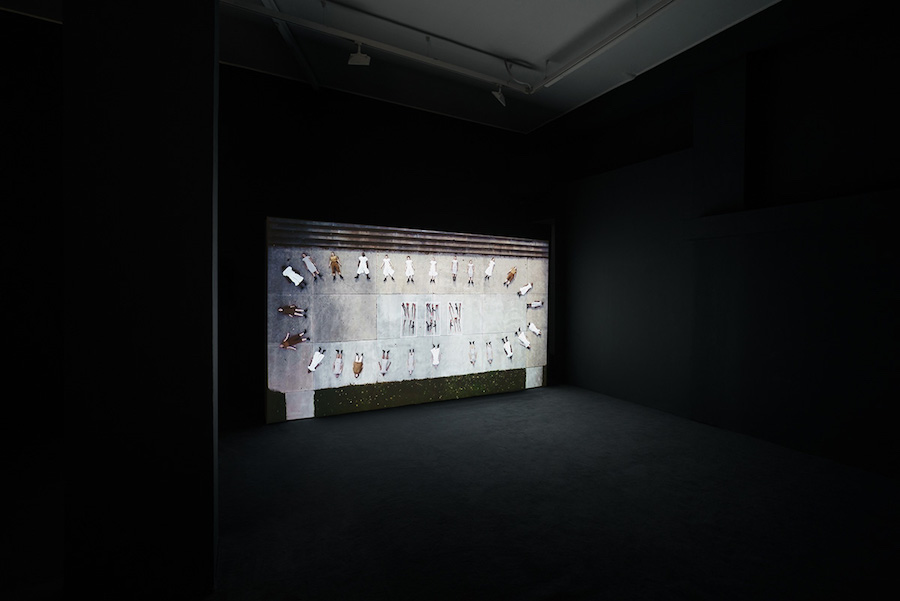

YB: The exhibition features my latest film The Undertaker together with a group of prints and objects, all of which take my two performances What If Women Ruled the World (2017-2018) and Bury Our Weapons, Not Our Bodies! (2018) as points of departure and represent different elements based on the two. It started after the Philadelphia Museum of Art bought the Polish trilogy And Europe will be Stunned and was planning to install it and the same time invited me to work on a new commission. I offered them to do some sort of action – a staged protest – in the context of the United States’ Second Amendment that gives Americans the right to bear arms, which I had changed to the right to bury weapons. The historic context of Philadelphia is very specific, but of course this is about burying violence. I thought about it as part of a move that I would be happy to see happening in Israel; I would love it if Israelis buried their weapons. It’s such a part of the Israeli ethos: To have strength, to have an army.

MZ / SB: In your video works – in the exhibition Cast Off in Modena – there is a mixture of a documentary style and a mode of filming, taken from Zionist propaganda films of the 1920s and 1930s, with moments that are almost ironic. What role does ambiguity play within these works that are on the borderline between reality and fiction?

YB: Ambiguity has always been an important element of my work. Jacques Rancière notes that reality must be fictionalized in order to be thought of, and I’d like to think of that as a starting point for my artistic practice. As you say, my films are not really documentaries, at least not documentaries according to a conservative definition. My interest in documentary lies in the space between the real and the fiction. When I go to shoot new film I often search for those documentary and authentic moments that appear on the street while shooting a scene and often I like to include them in the edit. What stands in the center of my practice is the documentation of fictional reality, which I create based on our world and everyday life. I like to explore what happens when placing a fictional element within reality – what it does to our real world, how it challenges the real given conditions and how it provokes the audience.

MZ / SB: Referring to your artist’s ongoing interdisciplinary project “What if Women Ruled the World?” (and ongoing project from 2016) I’d like to ask you what do you think about the relation of feminism with peace? And how did you develop an answer through the cast of such work? (I’m thinking also about a specific context, that is Dilar Dirik article Feminism pacifism or passive-ism? published on Open Democracy

YB: More than anything else, What if Women Ruled the World is an experiment. The title itself suggests that the project doesn’t try to make a statement such as “the world would have been a better (or worse) place if women ruled it”. The question of what if women ruled the world came to my mind a few years ago when I was thinking about the status quo of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. After years of frustration of the reality I started to imagine what could have happened if women ruled the political situation in both Israel and in Palestine. Would the conflict then be solved? Would the reality be different at all? Of course, we are not talking here about keeping the same structures while changing the gender of the people at the top – that would probably not change anything. We are talking here about the existing mechanisms that rule our world, which were historically developed by men in power. And naturally, thinking about this question in the Israeli-Palestinian context made me think in a broader sense: what if women ruled the whole world? In that sense, the project aims to put in question everything we know about political structures. I am quite sure that if I had an answer to the question I would have probably not worked on such a project. Still it’s important to remember that in parallel to the global artistic efforts to react to our crazy reality, we are witnessing some actual political and social events around the world that remind us that we are on the right way. Five young women are now at the head of the leadership in Finland, the protest regarding the climate change led by young people from all corners of the world, the entire #metoo affair and the fact the Harvey Weinstein was now convicted, a symbolic case that sends a clear sign – all these have a major impact not only on a pragmatic level, but also on a more deep and psychological level, it affects our mind, our perception of what is possible and where limits pass. Not only for ourselves, but mainly for the younger generations who will need to take charge of our world.