English version below —

Prima che lo sguardo si adatti alla luce, qualcosa accade: il tempo si fa vapore, la materia si raccoglie in silenzio, come se il mondo stesse per pronunciarsi sottovoce. Entrando nello spazio, la luce cambia passo — scende con lentezza, si trattiene nell’aria, avvolge ogni superficie come un respiro che cerca forma. È da questo silenzio sospeso che prende avvio Čučukstēt my hour, prima personale istituzionale di Daiga Grantina nel Regno Unito, a cura di Vittoria de Franchis.

Il titolo, un ibrido linguistico che intreccia il verbo lettone čučukstēt (“mormorare”) all’inglese my hour, suggerisce un tempo che non scorre ma mormora, che vibra come una superficie liquida attraversata dalla luce: un doppio tempo, collettivo e personale, condiviso e segreto, radicato nella lingua e nella memoria, ma anche nel respiro dell’esperienza sensibile.

Grantina, nata a Riga e residente a Parigi, da anni costruisce un lessico scultoreo che sfugge a ogni fissità formale. Le sue opere si compongono e si dissolvono nello stesso gesto, come se la materia — sintetica o organica, traslucida o opaca — trovasse equilibrio solo nel contatto con lo spazio. In questa mostra londinese, tale equilibrio si affina in una partitura di presenze minime: superfici sospese, forme che assorbono e rifrangono la luce, strutture leggere che rivelano la porosità della visione.

Il punto di partenza è un episodio reale ma carico di simbolismo: il giorno della prima visita dell’artista alla sede della Fondazione Nicoletta Fiorucci, l’orologio esterno — solitamente fermo — segnava esattamente l’ora del suo arrivo. Da questa coincidenza nasce il filo della mostra, che trasforma il tempo in materia plastica, in ritmo interno dell’opera. Il mormorio evocato dal titolo non appartiene soltanto alla voce, ma al movimento invisibile che attraversa la scultura, al modo in cui essa modula lo spazio e lo restituisce come eco.

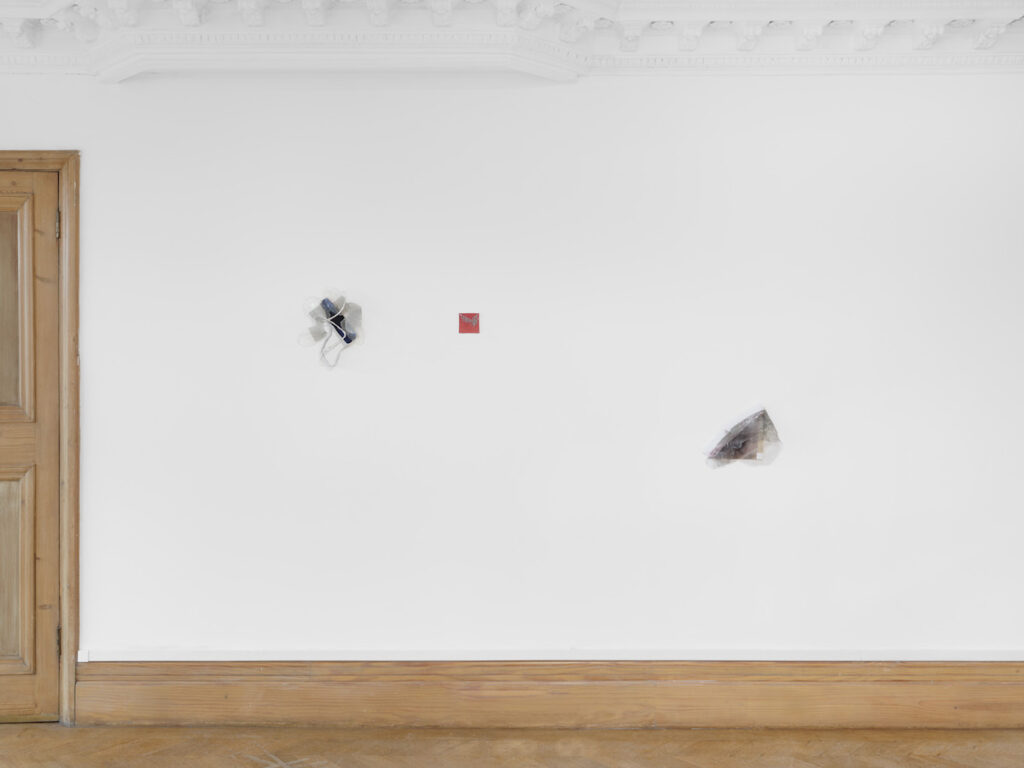

Grantina non costruisce oggetti, ma condizioni di visibilità. Ogni elemento partecipa di un sistema più ampio, dove luce, colore, ombra e trasparenza si contaminano. Le sculture murali, concepite come light catchers, sono spartiti di un linguaggio astratto: si dispongono lungo le pareti in una coreografia circolare, invitando il corpo dello spettatore a muoversi lentamente, a lasciarsi assorbire dal ritmo della visione. Il cerchio, figura ricorrente nel suo immaginario, diventa principio generativo — forma che respira — e si manifesta in assemblaggi puntinistici di perle e chiodi cilindrici, come galassie condensate in superficie.

Durante la residenza alla Villa Medici di Roma, Grantina aveva osservato i pini marittimi che si innalzano come colonne leggere, “colonne per le nuvole”, li ha definiti. Da quell’immagine è nata una metamorfosi che attraversa l’intera mostra. Le strutture verticali diventano punti d’appoggio per forme che si librano, come se l’aria stessa avesse trovato consistenza. Il passaggio tra elementi sospesi e altri ancorati al muro disegna un equilibrio instabile, dove ogni gesto scultoreo è anche un gesto d’ascolto.

“Solo i pini hanno appreso il passo delle nuvole,” affermava Cristina Campo. In quella lentezza verticale, quasi orante, si riconosce il ritmo silenzioso che attraversa le opere di Grantina. Come nelle parole di Tagore, “tra le cime dei pini passano le nuvole, e in ogni respiro della foresta c’è la voce del cielo,” anche nella sua geografia il paesaggio non è sfondo ma organismo respirante, un continuum di aria e materia. Tra queste due immagini — la contemplazione terrestre di Campo e il respiro cosmico di Tagore — si disegna una continuità di tempo e di sostanza: la nuvola non è più il contrario del pino, ma la sua estensione. Radice e vapore condividono un medesimo ritmo, una soglia di metamorfosi dove l’aria si fa corpo e il corpo si fa aria.

E proprio le nuvole, in Čučukstēt my hour, diventano figura del pensiero stesso: presenze mobili, provvisorie, che trattengono la luce senza possederla. La loro forma non è mai data, ma sempre in divenire — un archivio di possibilità atmosferiche che mutano con lo sguardo. Come nelle sculture di Grantina, anche nella nuvola la visione è un atto di durata, un esercizio di attenzione al transitorio. L’artista accoglie questa lezione naturale, traducendola in materia sensibile: le sue opere non rappresentano le nuvole, le imitano nel modo di esistere, sospese tra densità e disgregazione, tra corpo e respiro.

Una scultura sospesa, di fronte alla finestra, cattura il mutare della luce esterna e lo restituisce come movimento interno: un continuo slittamento tra trasparenza e ombra, presenza e assenza. Il suo oscillare impercettibile allinea per un attimo lo sguardo con le traiettorie del cielo, facendo coincidere nuvola, colonna, lampo — tre figure che condensano la tensione tra durata e improvvisazione.

Davanti a quella finestra, che si apre direttamente sul Tamigi, la scultura assume la forma di una nuvola terrestre: non più trattenuta dal soffitto, ma sospesa tra il fiume e il cielo, tra il movimento delle acque e quello delle correnti d’aria. È come se l’opera si lasciasse attraversare dal respiro stesso della città: la luce che rimbalza sull’acqua penetra nello spazio espositivo, frantumandosi in riflessi mobili che sembrano prolungare il battito del fiume dentro la scultura. In certi momenti, la luce londinese — lattea, instabile, sempre in bilico tra opalescenza e grigio — avvolge la materia, ne scioglie i contorni fino a farla sembrare un frammento di cielo trattenuto al suolo. Il Tamigi diventa allora un grande specchio atmosferico, un dispositivo ottico che restituisce all’opera la sua origine liquida, la sua natura di mormorio visivo. Come sostiene Emanuele Coccia, viviamo tutti in una mescolanza d’aria: respiro, luce, polline, vapore. L’aria è il primo habitat, la casa comune in cui le forme si trasformano e si scambiano sostanza. In questa mostra, la scultura di Grantina sembra praticare la stessa legge della metamorfosi vegetale: trasmigra tra stati, assorbe luce come clorofilla, restituisce visibilità come fotosintesi. La nuvola non rappresenta il cielo: lo fa passare. Così l’opera: non imita il mondo, lo respira; lo lascia circolare, come se la materia potesse farsi foglia e la foglia luce. In questo regime aereo, tempo e visione coincidono: ciò che vediamo è già un passaggio di sostanze, un lessico di scambi che tiene insieme l’umano e il non umano, il pino e la nuvola, l’acqua e il colore.

Sull’altra riva del fiume, tra gli alberi di Battersea, c’è una Pagoda che veglia. Lunare, immobile, si alza dal respiro dell’acqua come una preghiera che ha trovato forma. È nata per ricordare la pace, dopo il fuoco. Da qui, attraverso la finestra, la si scorge come un punto di quiete nel movimento del fiume. Anche la scultura sembra guardarla: due presenze che non si parlano, ma si riconoscono. La Pagoda sale, l’opera discende, e nel mezzo scorre il Tamigi — un respiro che passa da una sponda all’altra. Quando la luce cambia, per un attimo la nuvola di Grantina e il bianco del tempio si confondono: non più due cose, ma lo stesso fiato trattenuto tra cielo e acqua. In quell’istante, la città diventa parte integrante del lavoro, un paesaggio interiore che si deposita sulla materia come vapore.

Ciò che distingue Čučukstēt my hour dalle precedenti mostre di Grantina è l’emergere di un nuovo minimalismo pittorico, dove la materia sembra farsi pittura senza perdere la propria tridimensionalità. Le perle colorate e i chiodi creano superfici che vibrano come membrane, evocando la trama di un dipinto astratto o il pixel di un’immagine digitale. In questa traslazione, la scultura non rinuncia alla propria fisicità, ma la trasforma in un campo di energia, in una tensione tra luce e densità. Il lavoro dell’artista appare sempre più orientato verso una fenomenologia del sensibile: la sua pratica non racconta, ma accade. È un linguaggio fatto di intermittenze, di “scintille di sentimento senza risoluzione”, come afferma lei stessa. Ogni opera è un frammento che si apre all’altro, che chiede di essere attraversato con lo sguardo e con il corpo. L’idea di mormorio si traduce in un tempo che non conosce compimento, un tempo circolare che coincide con l’atto stesso del vedere. In un momento storico in cui la scultura tende spesso verso la monumentalità o l’iper-materialità, Grantina propone un’altra via: quella della leggerezza come intensità, della forma come respiro condiviso. Le sue opere non occupano lo spazio, lo ascoltano, lo modulano, lo restituiscono in forma di percezione. Alla fine del percorso, lo spettatore si ritrova dentro un cerchio di luce, come in una lente che concentra e dissolve. È lì che il tempo torna a mormorare: non come nostalgia, ma come promessa di un nuovo inizio.

Nella traiettoria di Grantina — dal Padiglione lettone della 58ª Biennale di Venezia (2019), Saules Suns, fino a questa mostra londinese — si può leggere la costante ricerca di un equilibrio tra materialità e respiro, tra costruzione e dissolvenza. Se allora l’opera sembrava nascere dal sole e dalla terra, ora pare generarsi dal cielo e dall’acqua. Čučukstēt my hour segna una maturità luminosa: la scultura non è più soltanto forma, ma modo d’essere del tempo — il punto in cui la materia si fa respiro e il respiro diventa mondo.

E l’ora, infine, non è un istante da possedere, ma un’eco che risuona senza mai coincidere del tutto con il proprio nome: un fluire, un apparire che si offre solo nell’attimo in cui si sottrae, come un respiro che si dissolve nell’aria.

Cover: Daiga Grantina, Čučukstēt my hour, at the Nicoletta Fiorucci Foundation. Courtesy the artist and the Nicoletta Fiorucci Foundation. Ph. Eva Herzog

The Murmuring of Time. Daiga Grantina at the Nicoletta Fiorucci Foundation, London

Text by Rita Selvaggio —

Before the gaze adjusts to light, something happens: time turns to vapour, and matter gathers in silence, as if the world were about to speak in a whisper. Entering the space, light alters its pace — it slows, lingers in the air, enveloping every surface like a breath searching for form. From this suspended stillness unfolds Čučukstēt my hour, Daiga Grantina’s first institutional solo exhibition in the United Kingdom, curated by Vittoria de Franchis.

The title, a linguistic hybrid that entwines the Latvian verb čučukstēt (“to murmur”) with the English my hour, evokes a temporality that does not flow but murmurs — vibrating like a liquid surface crossed by light. It speaks of a double time: collective and personal, shared and secret, rooted in language and memory yet attuned to the breath of sensory experience.

Born in Riga and based in Paris, Grantina has long been constructing a sculptural lexicon that resists formal fixity. Her works come together and dissolve in the same gesture, as if matter — synthetic or organic, translucent or opaque — could find balance only through its contact with space. In this London exhibition, that equilibrium refines itself into a score of minimal presences: suspended surfaces, forms that absorb and refract light, delicate structures that reveal the porosity of vision.

The exhibition begins with a real event, charged with symbolism: on the day of the artist’s first visit to the Nicoletta Fiorucci Foundation, the clock outside — usually stopped — showed precisely the hour of her arrival. From this coincidence unfolds the thread of the exhibition, transforming time into plastic matter, into the inner rhythm of the work. The murmur suggested by the title belongs not only to voice but to the invisible motion that traverses the sculpture — to the way it modulates space and gives it back as echo.

Grantina does not build objects but conditions of visibility. Each element participates in a wider constellation where light, colour, shadow, and transparency interpenetrate. The wall-based sculptures, conceived as light catchers, unfold like the score of an abstract language: arranged along the walls in a circular choreography, they invite the viewer’s body to move slowly, to be absorbed into the rhythm of seeing. The circle — a recurring figure in her imagination — becomes a generative principle, a form that breathes, manifesting in pointillist constellations of beads and cylindrical nails, like galaxies condensed upon a surface.

During her residency at the Villa Medici in Rome, Grantina observed the maritime pines that rise like slender columns — “columns for the clouds,” as she called them. From that image was born a metamorphosis that traverses the entire exhibition. The vertical structures become points of balance for forms that hover, as though air itself had gained substance. The dialogue between suspended elements and those anchored to the wall creates a delicate instability, where every sculptural gesture is also a gesture of listening.

“Only the pines have learned the pace of clouds,” wrote Cristina Campo. In that vertical slowness, almost prayerful, one recognises the silent rhythm that breathes through Grantina’s work. And as Tagore wrote, “Among the tops of the pines drift the clouds, and in every breath of the forest is the voice of the sky.” Within her geography too, the landscape is not backdrop but breathing organism — a continuum of air and matter. Between these two images — Campo’s terrestrial contemplation and Tagore’s cosmic breath — runs a continuity of time and substance: the cloud is no longer the opposite of the pine, but its extension. Root and vapour share the same pulse, a threshold of metamorphosis where air becomes body and body turns to air.

In Čučukstēt my hour, clouds become figures of thought itself — mutable, provisional presences that hold light without possessing it. Their form is never fixed but always in becoming, an archive of atmospheric possibilities that shift with the gaze. As in Grantina’s sculptures, the act of seeing becomes one of duration, an exercise in attending to the transient. The artist embraces this natural lesson, translating it into a sensitive material: her works do not represent clouds, but imitate their way of existing — suspended between density and dissolution, between body and breath.

A single hanging sculpture, placed before the window, captures the shifting light outside and returns it as inner movement — a continuous slippage between transparency and shadow, presence and absence. Its imperceptible sway aligns the viewer’s gaze, for a brief instant, with the trajectories of the sky, fusing cloud, column, and flash — three figures that condense the tension between persistence and improvisation.

Before that window, which opens directly onto the Thames, the sculpture assumes the form of a terrestrial cloud: no longer tethered to the ceiling but suspended between river and sky, between the motion of water and the currents of air. It is as if the work were traversed by the city’s own breath — the light bouncing off the river enters the room, fragmenting into shifting reflections that seem to prolong the river’s pulse within the sculpture. At certain hours, the London light — milky, unstable, poised between opalescence and grey — enfolds the material, softening its contours until it appears like a fragment of sky held close to the ground. The Thames becomes an atmospheric mirror, an optical device returning to the work its liquid origin, its nature as visual murmur.

As Emanuele Coccia reminds us, we all live within a mingling of air: breath, light, pollen, vapour. Air is our first habitat — the shared home in which forms transform and exchange substance. In this exhibition, Grantina’s sculpture seems to obey the same law of vegetal metamorphosis: it migrates between states, absorbs light like chlorophyll, and releases visibility like photosynthesis. The cloud does not represent the sky; it lets it pass through. So too the work: it does not imitate the world, it breathes it — allowing it to circulate, as if matter itself could turn to leaf and the leaf to light. Within this aerial regime, time and vision coincide: what we see is already a passage of substances, a lexicon of exchanges that binds together the human and the non-human, the pine and the cloud, water and colour.

On the opposite bank of the river, among the trees of Battersea, a Pagoda keeps watch. Moonlike, still, it rises from the breath of the water like a prayer that has taken form. It was built to remember peace, after fire. Seen from here, through the window, it appears as a single point of stillness within the river’s motion. The sculpture seems to gaze back at it: two presences that do not speak, yet recognise one another. The Pagoda ascends, the work descends, and between them the Thames flows — a breath moving from one shore to the other. When the light shifts, for an instant Grantina’s cloud and the whiteness of the temple merge: no longer two things, but the same held breath suspended between sky and water. In that moment, the city becomes part of the work itself, an interior landscape settling upon matter like vapour.

What distinguishes Čučukstēt my hour from Grantina’s previous exhibitions is the emergence of a new pictorial minimalism, in which matter seems to turn to painting without relinquishing its three-dimensionality. The coloured beads and nails create surfaces that vibrate like membranes, evoking both the weave of an abstract painting and the pixelated shimmer of a digital image. In this translation, sculpture does not abandon its physicality but transforms it into a field of energy — a tension between light and density. Grantina’s practice seems increasingly oriented toward a phenomenology of the sensible: her work does not narrate, it happens. It is a language of intermittence, of what she herself calls “sparks of feelings without resolution.” Each work is a fragment that opens toward the other, asking to be traversed by both gaze and body. The notion of murmur becomes a temporality without completion, a circular time that coincides with the act of seeing itself.

In an age when sculpture often inclines toward monumentality or hyper-materiality, Grantina proposes another path: that of lightness as intensity, of form as shared breath. Her works do not occupy space; they listen to it, modulate it, and return it in the guise of perception. At the end of the journey, the viewer finds themself inside a circle of light, as if within a lens that both concentrates and dissolves. There, time begins to murmur again — not as nostalgia, but as the promise of a new beginning.

Across Grantina’s trajectory — from Saules Suns, the Latvian Pavilion at the 58th Venice Biennale (2019), to this London exhibition — one reads the steady pursuit of equilibrium between materiality and breath, between construction and dissolution. If then her work seemed to rise from the sun and the earth, now it appears to be born of sky and water. Čučukstēt my hour marks a luminous maturity: sculpture is no longer merely form, but a mode of being in time — the point where matter becomes breath, and breath becomes world.

And the hour, finally, is not an instant to be possessed, but an echo that never fully coincides with its own name: a flow, an appearing that offers itself only in the moment it withdraws, like a breath dissolving into air.

Cover: Daiga Grantina, Čučukstēt my hour, at the Nicoletta Fiorucci Foundation. Courtesy the artist and the Nicoletta Fiorucci Foundation. Ph. Eva Herzog