[nemus_slider id=”64089″]

English text below

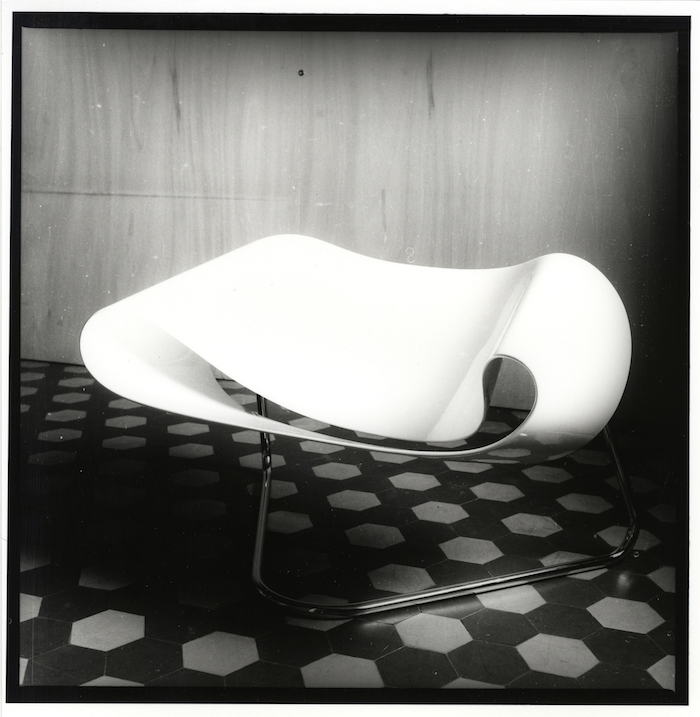

Architetto e fotografo, Cesare Leonardi (Modena, 1935), nel corso di una carriera professionale durata più di quarant’anni ha continuamente messo in discussione il confine tra progettazione e pratica artistica. Nonostante il successo dei primi oggetti di design (come la poltrona Dondolo disegnata con Franca Stagi nel 1967, selezionata per la celebre esposizione Italy: The New Domestic Landscape al MoMA) la maggior parte dell’opera di Leonardi è ancora poco conosciuta. La mostra Cesare Leonardi: Strutture – ospitata fino al 17 aprile 2017 a Villa Croce a Genova e a cura di Joseph Grima e Andrea Bagnato – è stata organizzata in stretto contatto con l’Archivio Leonardi e mette in luce la dimensione personale e allo stesso tempo poliedrica della sua produzione.

Seguono alcune domande ai curatori e un testo di Joseph Grima —

ATP: Una domande su tutte mi sembra significativo trovare risposta. Perché, a vostro parere, la maggior parte l’opera di Cesare Leonardi è ancora poco conosciuta, nonostante la sua carriera sia punteggiata di tappe importanti tappe, tra tutte la mostra The New Domestic Landscape al MoMA (1972)?

Joseph Grima e Andrea Bagnato: Quello che ci sembra di capire dalle nostre ricerche e conversazioni è che Leonardi non è mai stato interessato alla fama e ai riconoscimenti. Il suo lavoro è peculiare proprio per la volontà di mantenere un’assoluta integrità, senza scendere a compromessi con le esigenze del mercato e dei mezzi di comunicazione. Leonardi voleva lavorare su quello che lo interessava (come gli alberi) in modo esaustivo, dedicando tutto il tempo necessario; per fare questo era necessario tenersi lontano dalla scena architettonica. Questo spiega perché non sia entrato nel circolo dell’architettura milanese degli anni settanta nonostante l’evidente successo dei suoi primi lavori.

ATP: La mostra a Villa Croce mette a fuoco due dimensioni di Cesare Leonardi: quella personale e quella più strettamente legata alla sua ricerca e produzione. Come avete conciliato questi due aspetti? Come sono espressi in mostra? Il percorso espositivo è stato suddiviso in tre macro aree d’indagine: sedie, ombre e alberi. Mi raccontate brevemente questa tripartizione?

JG / AB: Ci è sembrato importante che la mostra raccontasse il modus operandi di Leonardi, che come detto sopra era esaustivo e staccato da considerazioni di utilità pratica: le tre aree di indagine (sedie, ombre, alberi) rappresentano ciascuna almeno due decenni di lavoro.

Gli spazi di Villa Croce, che appunto era un’abitazione prima di diventare un museo, con la loro dimensione domestica ci hanno permesso di sottolineare come Leonardi lavorasse prima di tutto per se stesso: ogni stanza della mostra racchiude un singolo aspetto della sua produzione, ma il percorso nel suo insieme ripercorre tutta la biografia.

ATP: Per oltre vent’anni Cesare Leonardi si è dedicato a disegnare degli alberi. La raccolta di questi disegni ha avuto come esito il libro L’Architettura degli Alberi (1982). Nelle vostre ricerche sul suo lavoro, avete scoperto perché era ‘ossessionato’ dagli alberi? Come ha sviluppato questa sua ricerca in relazione alla progettazione di paesaggi?

JG / AB: Il progetto con cui Leonardi si è laureato a Firenze era un parco pubblico a Modena. Mentre ci lavorava, si accorse che nelle discipline architettoniche la conoscenza degli alberi era pressoché nulla. Come diceva spesso, gli architetti usano gli alberi come se fosse insalata, cioè a casaccio. Da qua nasce la volontà di studiare le caratteristiche di ogni specie arborea, le sue variazioni, la storia, l’habitat, e l’impatto sullo spazio urbano. Leonardi è stato visionario in questo, perché la sua ricerca sugli alberi anticipa di molto l’attenzione corrente per le piante “spontanee” e per il progetto del paesaggio che presta attenzione alle interazioni ecologiche tra specie diverse (si veda per esempio il lavoro di Gilles Clement e Piet Oudolf).

Curatorial Statement by Joseph Grima —

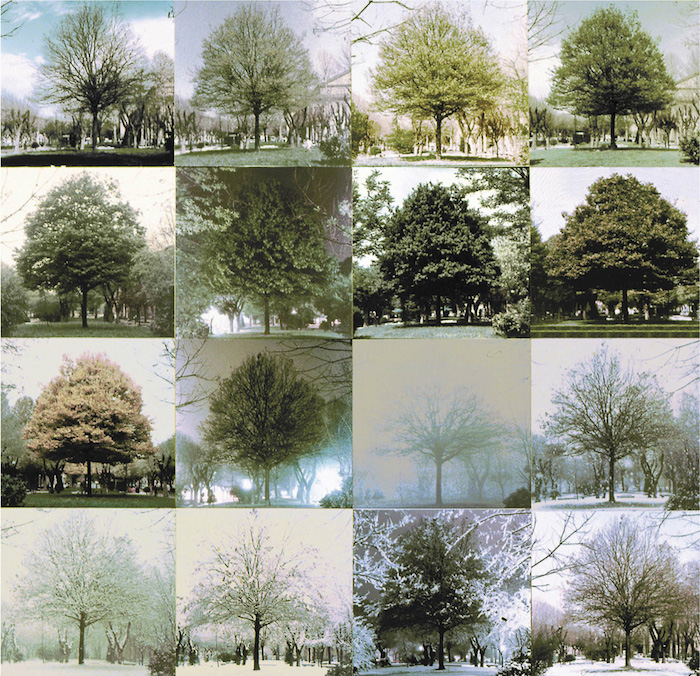

“About five years ago, in a secondhand bookshop in Milan, I bought a book that instantly became my most cherished (and I have quite a few!). L’Architettura degli Alberi by Cesare Leonardi is a poetic ode to the magnificence of trees, the life’s work of an architect who was obsessed by their effortless beauty and offended by the callousness with which most architects treated their presence. Assisted by Franca Stagi, he spent 20 years traveling the world to photograph, measure and painstakingly hand-draw in ink over 100 varieties of trees, with and without foliage, scientifically documenting their seasonal chroma and shadow patterns.

He developed planting schemes to take the effort out of designing parks that would provide pleasant shade at various latitudes, and obsessively photographed his subjects over the months and years, observing their development and adaptation to their environment. Throughout all this time, working from a modest flat in suburban Modena, he remained almost completely unknown (to this day he has no Wikipedia page). To some extent he did achieve his aim, though – I remember friends telling me that scans of his drawings were often passed around among students on thumb drives in Italian schools of architecture in the late ’90s, though few knew where they came from…

Five years later, thanks to the great Giorgio de Mitri, I finally met him in his house in Modena. It turns out that Alberi is just the beginning of the incredible story of Cesare Leonardi. In his 30s he designed several chaise-longue and armchairs that were included in Italy: The New Domestic Landscape at MoMA in 1972. Yet soon after he had a change of heart; considering those pieces elitist, he devoted the following twenty years to designing an almost infinite set of chairs that could be made out of standard yellow formwork casting panels (€15 from Leroy Merlin). Another of his books, Solidi, collects dozens of blueprints for these designs – a sort of ante litteram open source furniture manual.

All this to say he instantly became my hero, and I’m incredibly happy that on Feb. 23 at 6pm, we’ll inaugurate a first retrospective of his work at Museo Villa Croce in Genova (organized by myself and Andrea Bagnato). This show is an anticipation of a larger and more exhaustive retrospective organized by the brilliant team at the Archivio Cesare Leonardi (Giulio Orsini, Andrea Cavani, Paolo Credi and Veronica Bastai) that will be held later this year at the Galleria Civica di Modena. The members of the Fondazione deserve special credit for the incredible work they’ve patiently carried out over the last decade to catalogue Leonardi’s prodigious volume of work.

It’s a pleasure and a privilege to pay tribute to this extraordinary architect and the people he worked with over 5 decades, and very gratifying that although his health isn’t great he’s still around to see his life’s work didn’t go unnoticed. The world needs more trees, and more Cesare Leonardi’s.”

CESARE LEONARDI STRUTTURE

Museo arte contemporanea Villa Croce

Until april 17, 2017

Organized by Joseph Grima and Andrea Bagnato

in collaboration with Archivio Architetto Cesare Leonardi

The Villa Croce Museum of Contemporary Art presents the first comprehensive exhibition on the work of Cesare Leonardi (b. 1935, Modena, Italy). An architect and photographer, in the course of a career that spanned more than four decades Leonardi has continuously challenged the boundary between design and artistic practice. In spite of the recognition gained by his early furniture design – such as the Rocking chair, designed with Franca Stagi in 1967 and featured in the foundational MoMA exhibition Italy: The New Domestic Landscape – most of Leonardi’s oeuvre has remained little known, even within Italy. The exhibition Cesare Leonardi: Strutture, organized in close cooperation with Leonardi’s archive, sheds light on a body of work that is at once intimate and multifaceted.

The exhibition uses the historical backdrop of Villa Croce to explore three broad topics — chairs, shadows, trees — which preoccupied Leonardi throughout his career, and on which he worked across very different scales. In parallel with the acclaimed work on fiberglass furniture, in the 1960s Leonardi and Stagi embarked on a twenty-year-long project to redraw common trees in order to provide a missing tool for landscape designers. The result, is a group of more than 360 hand-inked scale drawings, published in the book L’Architettura degli Alberi (1982) that is now out of print; poetic and obsessive, it goes far beyond its original intentions. A focal point of the exhibition is a series of more than fifty original drawings.

The systematic study of trees, conducted through a large photographic survey that took Leonardi to travel around the world, was propaedeutic to a series of landscape projects based on the idea of a non-hierarchic network. The structure, potentially endless, regulates the position of each element in space.

In the 1980s, as a reaction to the oil crisis that made fiberglass no longer sustainable, Leonardi began working with simple timber formwork. Decontextualized and combined according to increasingly complex patterns, the yellow boards became a series of furniture termed Solidi. These are veritable sculptures in which Leonardi explores the idea of an infinite permutation of the same element. Similarly, photography informed and played along Leonardi’s entire career, reflecting both his interest for abstract form and his analogic working method, which was always based on iterations and sequences. While retaining a highly original language, Leonardi entertained productive exchanges with important figures in the regional scene, such as photographer Luigi Ghirri and artist Claudio Parmiggiani; nonetheless, he always chose to shy away from publicity.

Cesare Leonardi: Strutture is an intimate journey inside Leonardi’s extraordinary body of work where, in spite of the ever-shifting scales of design, it is possible to see a constant tension between work of art and craftsmanship, and between single element and structure.

The exhibition at Villa Croce will be followed by a retrospective at Galleria Civica di Modena, which is scheduled to open in September 2017.

Cesare Leonardi was born in Modena in 1935. After graduating in architecture in Florence in 1970, he returned to Modena and opened an architecture firm in partnership with Franca Stagi. The firm completed several projects at the interior, architectural and landscape scales, among which a swimming center in Vignola (1975) and the City of Trees in Bosco Albergati, Reggio Emilia (1998). In parallel, Leonardi continued to experiment with photography and darkroom techniques. He published several books, including L’Architettura degli Alberi with Franca Stagi (Milano: Mazzotta, 1982), Il Duomo di Modena. Atlante fotografico (Modena: Panini, 1985) and Solidi/Solids (Modena: Logos, 1995). Some of Leonardi’s works have been acquired by institutions such as The Museum of Modern Art in New York, and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.