English Text below —

“Non vi è nulla nell’universo che non sia una corrispondenza”.

— Emanuel Swedenborg, Il cielo e l’inferno

Nel lessico di Emanuel Swedenborg, ogni cosa sensibile è sempre già qualcosa d’altro: un corpo visibile attraversato da un ordine invisibile, una soglia permeabile tra il naturale e lo spirituale, il contingente e l’eterno. Il mondo, nel suo schema, non è che un sistema di corrispondenze: non analogie, ma iscrizioni reciproche, rifrazioni dell’interiorità nel paesaggio, del divino nel quotidiano. È da questa ipotesi ontologica che prende le mosse Hereafter, il progetto di Simon Moretti concepito per la Swedenborg House di Londra. Sede della Swedenborg Society, la casa è custode dal 1810 di un pensiero laterale e profetico che ha intrecciato teologia, scienze della natura, filosofia sperimentale e poetica dell’oltre. Dove Swedenborg immaginava un cosmo interconnesso di piani spirituali, Moretti dà forma a un campo visivo magnetico, popolato da immagini che non illustrano, ma si attivano come forze agenti.

Che cosa accade all’immagine quando si svincola dalla sua funzione rappresentativa? Quando smette di testimoniare e inizia a trapassare — a inquietare, a risuonare, a trapelare? La mostra si attiva come campo di co-presenza, come articolazione sensibile del tempo fuori asse, come esercizio di visione incarnata. La curatela — diffusa, discreta, stratificata — costruisce un dispositivo espositivo che si serve della Swedenborg House non come contenitore, ma come organismo. L’edificio georgiano, affacciato su Bloomsbury Way, nel cuore del quartiere che fu epicentro della mistica laica del Novecento, è trattato come uno scenario risonante che attiva una topografia percettiva distinta. Il titolo, Hereafter porta con sé una polisemia latente: “ciò che viene dopo”, ma anche “ciò che resta”, “ciò che segue”, “ciò che sopravvive”. In questo senso, la mostra si articola come una riflessione estetico-filosofica sul postumo, inteso non come epilogo ma come campo di resistenza alla linearità del tempo e di sfida alla continuità identitaria. Non sorprende che molte delle opere ruotino attorno a corpi dislocati, alla memoria affettiva, all’archivio come apparato pulsante. Il pensiero swedenborghiano funziona come un intercessore, una grammatica carsica. Tra ciò che permane e ciò che sopravvive, tra ciò che si mostra e ciò che ritorna, l’intero tracciato curatoriale si compone come una mappa dell’intangibile, articola una cartografia dell’invisibile, un intreccio di ritualità secolare, sintassi visionaria e pratica medianica del display.

Il suo impianto profondo si radica nel concetto di corrispondenza — nozione che, centrale in Swedenborg, ispirò Baudelaire nel celebre sonetto Correspondances (1857) e, con lui, l’intera costellazione simbolista. Come nei versi del poeta francese, “les parfums, les couleurs et les sons se répondent”, così anche in questa sede le immagini, i materiali e gli oggetti risuonano tra loro come segnali in un sistema aperto, non gerarchico ma visionario.

“Deborah Levy ha spesso immaginato la soglia non come un punto da attraversare, ma come uno spazio che resta aperto — una zona di attesa e possibilità, dove l’identità si scompone e si ricompone. È in questa sospensione attiva che si innesta il cuore pulsante di Hereafter: una mostra che non traduce ma trattiene, che non comunica ma intensifica. Le opere non si lasciano leggere: si fanno ascoltare, come se fossero voci che sopravvivono alla loro origine, ogni opera coinvolta lavora su un piano diverso del postumo: pittorico, archiviale, concettuale, materiale, visionario e questa pluralità dei registri non produce dispersione, ma densità, una pluralità di voci dislocate. Nel saggio in catalogo Strange Navigator, Jennifer Higgie descrive la mostra come un “conceptual project” orchestrato da Simon Moretti, un’operazione che mette in scena una “choreography of symbolic analogies”. In questa definizione si condensa la doppia natura della pratica di Moretti: da un lato, un lavoro di montaggio e connessione temporale – che chiama in causa il passato, l’altrove e il postumo – dall’altro, un’esplorazione del pensiero visivo come sistema di corrispondenze.

Il lavoro di Derek Jarman (K.Y., 1989), si staglia come una reliquia apocalittica. L’opera, una piccola natura morta costruita con detriti spiaggiati — lattine schiacciate, ciottoli, un fiore arrugginito — sembra appartenere a un mondo post-catastrofico dove la bellezza si annida nella decomposizione, nella perdita, nella fragilità delle cose residuali. L’opera di Jarman non solo incarna perfettamente i temi centrali di Hereafter — la transitorietà, la resurrezione simbolica, la tensione verso l’invisibile — ma ne radicalizza il tono funzionando come un talismano postumo, un ex-voto del desiderio e della vulnerabilità. Reliquiario dell’invisibile, oggetto liminare che porta con sé le impronte di un’assenza e il riverbero di un oltre. È in questa tensione che si inscrive l’intero progetto: nell’anatomia dell’altrove che non si vede, ma si percepisce — come una voce interiore, un’eco sopravvissuta, un gesto d’amore che ha attraversato la notte. Il collage di Goshka Macuga (2014) lavora sulla frizione tra documento e finzione, tra storia e anacronismo, in esso l’archivio diventa superficie di invocazione, materia da interrogare più che da conservare. È una macchina iconografica perturbante: non si limita a “mostrare” ma a “rendere presente”. Nella stanza dove si trova Its Double (2019) di Donna Huddleston, il tempo pare sospeso tra teatralità e silenzio. Due figure si fronteggiano come riflessi interrotti: il disegno, realizzato a matita con precisione miniaturistica, trasforma il gesto grafico in atto sacrale. “Non c’è mai una sola direzione temporale nella soglia”, suggerisce Chloe Aridjis, e questa scena ambigua ne è la messa in atto visiva. Il dipinto Antiphon (2024) di Paul Heber-Percy si presenta come una tavola mistica: composizione cromatica rarefatta, ieratica, costruita per risonanza. Non c’è narrazione, né soggetto, ma uno spazio interiore fatto di ritmo e silenzio. È un’icona laica, un campo energetico in cui il guardare è già un atto di ricezione liturgica. A questa intensità visuale si si affiancano gli interventi dello stesso Simon Moretti. I due neon Double Vortex (after Emanuel Swedenborg) e Vortex Becoming (after Emanuel Swedenborg), entrambi del 2025 — agiscono come segni-soglia, elementi catalizzatori di senso e orientamento e rielaborano graficamente la figura del vortice, tema centrale nella cosmologia di Swedenborg e simbolo del moto ascensionale dello spirito. La loro luce è un vettore simbolico: curva lo spazio, guida lo sguardo, orienta l’immaginazione. Come afferma lo stesso Moretti: “Curare significa disporre degli spettri, modulare la loro frequenza, lasciarsi attraversare dalle loro interruzioni.”

In Untitled (91) di Haris Epaminonda (2023), una minuscola composizione grafica sembra trattenere un segno archeologico non decifrabile: è più un restauro che un disegno, una rievocazione che un’origine. Lo stesso si può dire per Eclipse (2023) di David Noonan: la sua superficie tessile, ottenuta con pigmenti liquidi su stoffa, non è né astratta né figurativa, ma piuttosto un affresco cosmico del tempo che si nasconde. E sempre su un orizzonte visionario che si innesta l’opera di Linder, Superautomatisme Grand Jeté XVII (2018), piccolo smalto su pagina di rivista: una figura femminile, una ballerina in tonalità seppia, abbassa lo sguardo mentre vortici di rosso, nero, bianco e giallo si avvolgono attorno a lei come fossero pulsazioni incarnate di energia. La pittura diviene così eco visiva di una rivelazione interiore, dove materia e trascendenza si intrecciano. La piccola ma densissima opera su carta di Joëlle Tuerlinckx lavora sul margine sottile tra l’atto del camminare e il gesto del pensare, tra traccia e riflessione. Theory of Walking (2008) non è semplicemente il suo titolo: è una dichiarazione d’intenti che trasforma il passo in scrittura e la pagina in luogo. La carta da fotocopie, materiale ordinario e fragile, accoglie una stampa laser e un intervento con pennarello su sottobicchiere da birra — elemento residuale, quotidiano, quasi triviale, che diventa modulo di annotazione, spostamento, presenza. Il frammento fa parte della serie PLACE–PAGE, che già nel nome evoca la sostituibilità tra spazio e scrittura, tra supporto fisico e dispositivo mentale.

Le sculture A and B (2021–22) di Daniel Silver, in ceramica dipinta, somigliano a icone fossili di un’umanità perduta: corpi che hanno dimenticato la propria funzione ma conservano ancora una forma. Sono reliquie incarnate, frammenti organici di una biologia spirituale. Michael E. Smith — con un assemblaggio privo di titolo (Untitled 2023), fatto di legno, smalto e una ciotola — compone un oggetto che non è né scultura né readymade, ma piuttosto un residuo del tempo. La sua posizione nel vuoto della stanza genera un campo silenzioso, come un’interruzione del flusso percettivo.

Non è il passato che ritorna ma una sua vibrazione trattenuta, un impulso che fende il tempo come un richiamo senza radice. Le opere storiche incluse in Hereafter non svolgono una funzione genealogica: esse agiscono come forme di pensiero dormienti, portatrici di un’intensità che non appartiene più alla storia, ma all’interiorità del tempo. Sono immagini che hanno atteso il momento della loro riattivazione, sopravvivendo come relitti simbolici, come nodi di senso ancora in potenza che si fanno presenti come epifanie interiori. Animal Skull and Hand (1950s) di Eileen Agar è più di un collage: è un engramma sensibile, un condensato mnemonico in cui il corpo e la natura si fondono in un archetipo visivo. In Grotto of the Sun and Moon, Nicaragua (1952), Ithell Colquhoun non dipinge un luogo, ma un’interiorità paesaggistica: l’acquerello diventa spazio di metamorfosi, soglia del mentale. Autumn Evening, Bruges (ca. 1900) di Pelle Swedlund si presenta come una visione sospesa tra il visibile e il numinoso: il colore è atmosfera pensante, eco spirituale di una memoria in dissoluzione. Con George Frederic Watts, la morte non è un soggetto iconogafico, ma una categoria formale: The Court of Death (1868-1870) e Love & Death (1880 circa) non narrano, non illustrano, ma interrogano il visibile nel momento in cui si apre verso l’invisibile. Le sue immagini, incerte e ardenti, esistono nella zona liminale tra pensiero e apparizione, come se cercassero, ancora oggi, una forma adeguata a dire ciò che non può essere detto.

Il programma pubblico della mostra si è articolato in momenti cruciali. La proiezione del film Faust (1926) di F.W. Murnau, accompagnata dalla sonorizzazione dal vivo di Maxwell Sterling nella Swedenborg Hall, ha rappresentato uno degli apici percettivi del progetto. L’estetica espressionista di Murnau — fatta di ombre mobili, silhouettes esatte, dissolvenze temporali — ha trovato un contrappunto elettroacustico nella musica di Sterling, che ha trasformato la visione in trance collettiva. Il cinema, qui, non era più dispositivo narrativo, ma medium necromantico. Altro momento rilevante è stata la proiezione del film di Ben Rivers, The Sky Trembles and the Earth Is Afraid and the Two Eyes Are Not Brothers (2015), presentato lo scorso aprile. Tratto da un racconto di Paul Bowles e girato tra le rovine desertiche del Marocco, il film si muove tra ethno-fiction e elegia metafisica. “Ci sono storie che iniziano dal punto in cui le voci si fanno eco,” scrive Aridjis, “Ben Rivers sembra inseguire la vibrazione che resta quando tutto il resto è stato rimosso.” Nel film la visione è una perdita di orientamento, un viaggio iniziatico senza ritorno, un’epifania percettiva. Rivers non filma l’aldilà, ma ciò che resta della sua ombra.

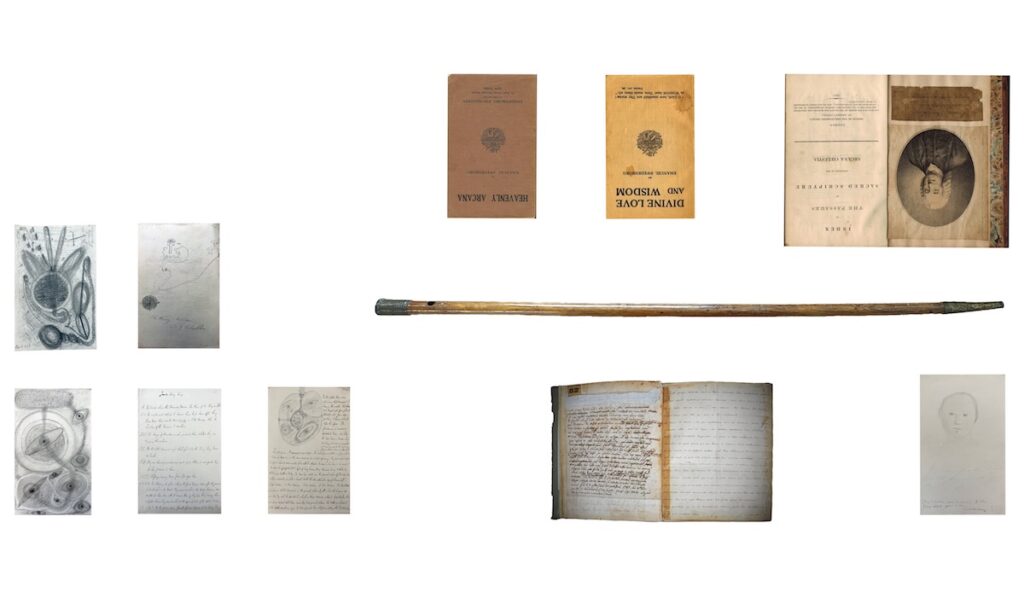

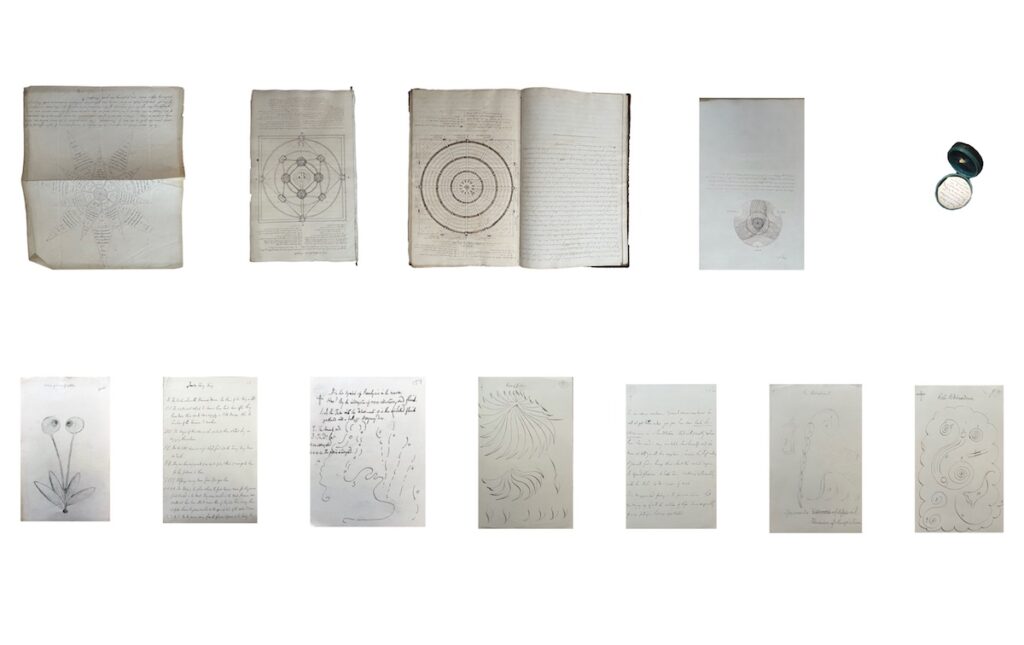

Il catalogo, ideato e curato da Moretti, è concepito come libro-oracolo.— raccoglie testi poetico-saggistici accompagnando la mostra come una sua estensione concettuale. Strutturato come un montaggio di voci che mette in dialogo le opere degli artisti con scritti di autori come Blake, Baudelaire, Poe, Mallarmé, Donne, Goethe e Colquhoun. La curatela stessa diventa parte del gesto artistico: un’architettura simbolica, diagrammatica, che si compone per affinità, analogie e risonanze inattese. In questo senso, il libro si configura come un “rebus temporale” e affettivo, un al di là estetico capace di ridisegnare le frontiere dell’esperienza.

In un tempo dominato dalla trasparenza coercitiva e dal dato, Hereafter rivendica l’opacità, il margine, l’irriducibile. Non è un’esposizione tematica: è un’invocazione, un campo semantico abitabile, un’interferenza duratura. Come affermava lo stesso Swedenborg, “The spiritual world is not elsewhere. It is the interior of things.

Anatomy of Elsewhere. Posthumous Thought and Mediumistic Visions in Hereafter

Text by Rita Selvaggio —

“There is nothing in the universe that is not a correspondence.”

— Emanuel Swedenborg, Heaven and Hell

In Emanuel Swedenborg’s lexicon, every perceptible thing is already something else: a visible body traversed by an invisible order, a permeable threshold between the natural and the spiritual, the contingent and the eternal. In his system, the world is not made up of analogies but of correspondences: reciprocal inscriptions, refractions of interiority within the landscape, of the divine within the everyday. It is from this ontological premise that Hereafter, the project by Simon Moretti conceived for the Swedenborg House in London, takes shape. Home to the Swedenborg Society since 1810, the house has preserved a lateral and prophetic mode of thought that interlaces theology, natural sciences, experimental philosophy, and a poetics of the beyond. Where Swedenborg envisioned an interconnected cosmos of spiritual planes, Moretti conjures a magnetic visual field populated by images that do not illustrate but act — as living forces.

What happens to the image when it breaks free from its representative function? When it ceases to testify and begins to penetrate — to unsettle, to reverberate, to seep through? The exhibition operates as a field of co-presence, a sensitive articulation of off-axis time, an exercise in embodied vision. The curatorial approach — diffuse, discreet, stratified — constructs an exhibitionary device that treats Swedenborg House not as a container but as an organism. The Georgian building on Bloomsbury Way, in the heart of a district once central to secular mysticism in the twentieth century, is approached as a resonant stage that activates a distinct perceptual topography. The title Hereafter carries latent polysemy: “what comes after,” but also “what remains,” “what follows,” “what survives.” In this sense, the exhibition unfolds as an aesthetic-philosophical reflection on the posthumous — not as epilogue but as a field of resistance to temporal linearity and a challenge to identity continuity. Unsurprisingly, many of the works orbit around displaced bodies, affective memory, and the archive as a pulsating apparatus. Swedenborgian thought functions as an intercessor, a submerged grammar. Between what endures and what survives, between what appears and what returns, the entire curatorial path becomes a map of the intangible, articulating a cartography of the invisible, a weave of secular rituality, visionary syntax, and a mediumistic display practice.

Its deep structure is rooted in the concept of correspondence—a notion central to Swedenborg, which inspired Baudelaire in his famous sonnet Correspondances (1857) and, with him, the entire Symbolist constellation. As in the French poet’s verse, where “perfumes, colours and sounds answer one another,” so too in this context do images, materials, and objects resonate among themselves like signals within an open, non-hierarchical, visionary system.

Deborah Levy has often imagined the threshold not as a point to be crossed, but as a space that remains open — a zone of waiting and possibility, where identity unravels and recomposes itself. It is within this active suspension that the vital core of Hereafter takes shape: an exhibition that does not translate but retains, that does not communicate but intensifies. The works do not lend themselves to reading: they must be listened to, as if they were voices surviving their own origin. Each piece engages a different register of the posthumous: painterly, archival, conceptual, material, visionary. And this plurality of registers does not disperse meaning—it generates density, a dispersed plurality of voices.

In her catalogue essay Strange Navigator, Jennifer Higgie describes the exhibition as a “conceptual project” orchestrated by Simon Moretti, a gesture that stages a “choreography of symbolic analogies.” Within this formulation lies the dual nature of Moretti’s practice: on one hand, a work of montage and temporal connection—calling upon the past, the elsewhere, and the posthumous; on the other, an exploration of visual thought as a system of correspondences.

Derek Jarman’s K.Y. (1989) stands out as an apocalyptic relic. The work, a small still life assembled from beached detritus—crushed cans, pebbles, a rusted flower—seems to belong to a post-catastrophic world where beauty nests in decomposition, in loss, in the fragility of leftover things. Jarman’s piece not only perfectly embodies the central themes of Hereafter—transience, symbolic resurrection, the pull toward the invisible—but it radicalizes their tone, functioning as a posthumous talisman, an ex-voto of desire and vulnerability. A reliquary of the invisible, a liminal object bearing the imprints of absence and the echo of an elsewhere. It is within this tension that the entire project takes shape: in the anatomy of an elsewhere that cannot be seen, but can be felt—like an inner voice, a lingering echo, a gesture of love that has travelled through the night.

Goshka Macuga’s collage (2014) operates on the friction between document and fiction, between history and anachronism: in it, the archive becomes a surface of invocation, a matter to be questioned more than preserved. It is a disquieting iconographic machine: it does not simply “show,” but rather “makes present.”

In the room where Donna Huddleston’s Its Double (2019) is installed, time seems suspended between theatricality and silence. Two figures face each other like broken reflections: the drawing, rendered in pencil with miniature precision, transforms the graphic gesture into a sacred act. “There is never just one temporal direction in the threshold,” suggests Chloe Aridjis, and this ambiguous scene visually enacts that insight.

Paul Heber-Percy’s painting Antiphon (2024) appears as a mystical panel: a rarefied, hieratic chromatic composition built through resonance. There is no narrative, no subject, only an inner space composed of rhythm and silence. It is a secular icon, an energetic field in which looking is already a liturgical act of reception.

This visual intensity is echoed by the contributions of Simon Moretti himself. His two neon works—Double Vortex (after Emanuel Swedenborg) and Vortex Becoming (after Emanuel Swedenborg), both from 2025—act as threshold-signs, catalytic elements of meaning and orientation. They graphically reinterpret the figure of the vortex, a central theme in Swedenborg’s cosmology and a symbol of the soul’s ascending motion. Their light is a symbolic vector: it bends space, guides the gaze, orients the imagination. As Moretti himself affirms: “To curate is to arrange spectres, to modulate their frequency, to let oneself be crossed by their interruptions.”

In Untitled (91) by Haris Epaminonda (2023), a tiny graphic composition seems to withhold an undecipherable archaeological trace: it is more a restoration than a drawing, more an evocation than an origin. The same could be said of Eclipse (2023) by David Noonan: its textile surface, made with liquid pigments on fabric, is neither abstract nor figurative, but rather a cosmic fresco of hidden time. Linder’s Superautomatisme Grand Jeté XVII (2018), a small enamel on a magazine page, is also inscribed within a visionary horizon: a sepia-toned female figure, a ballerina, lowers her gaze as vortices of red, black, white, and yellow swirl around her like embodied pulses of energy. The painting becomes a visual echo of an inner revelation, where matter and transcendence intertwine.

Joëlle Tuerlinckx’s small yet extremely dense work on paper operates at the fine edge between the act of walking and the gesture of thinking, between trace and reflection. Theory of Walking (2008) is not merely its title: it is a statement of intent, turning the step into script and the page into place. Photocopy paper — an ordinary and fragile material — hosts a laser print and a marker intervention on a beer coaster: a residual, every day, almost trivial object that becomes a unit of annotation, displacement, and presence. The fragment is part of the series PLACE–PAGE, which already in its title evokes the interchangeability between space and writing, between physical support and mental device.

The sculptures A and B (2021–22) by Daniel Silver, in painted ceramic, resemble fossil-like icons of a lost humanity: bodies that have forgotten their function but still retain a form. They are embodied relics, organic fragments of a spiritual biology. Michael E. Smith — through an untitled assemblage (Untitled 2023) made of wood, enamel, and a bowl — creates an object that is neither sculpture nor readymade, but rather a residue of time. Its placement within the emptiness of the room generates a silent field, like an interruption in the perceptual flow.

It is not the past that returns, but a vibration of it held in suspension—an impulse that cuts through time like a rootless call. The historical works included in Hereafter do not serve a genealogical function: they act as dormant forms of thought, bearers of an intensity that no longer belongs to history but to the interiority of time. These are images that have awaited the moment of their reactivation, surviving as symbolic relics, as nodes of latent meaning that emerge as inner epiphanies.

Eileen Agar’s Animal Skull and Hand (1950s) is more than a collage: it is a sensitive engram, a mnemonic condensation in which body and nature merge into a visual archetype. In Grotto of the Sun and Moon, Nicaragua (1952), Ithell Colquhoun does not paint a place, but a landscape of interiority: the watercolor becomes a space of metamorphosis, a threshold of the mental. Pelle Swedlund’s Autumn Evening, Bruges (ca. 1900) appears as a vision suspended between the visible and the numinous: color becomes thinking atmosphere, the spiritual echo of a dissolving memory. With George Frederic Watts, death is not an iconographic subject, but a formal category: The Court of Death (1868-1870) and Love & Death (1870) do not narrate, do not illustrate—they interrogate the visible at the very point it opens toward the invisible. His images, uncertain and burning, exist in the liminal zone between thought and apparition, as if still searching for a form adequate to express what cannot be said.

The public program of the exhibition unfolded through a series of crucial moments. The screening of Faust (1926) by F.W. Murnau, accompanied by a live soundtrack composed and performed by Maxwell Sterling in the Swedenborg Hall, marked one of the project’s perceptual peaks. Murnau’s expressionist aesthetic — composed of shifting shadows, sharp silhouettes, and temporal dissolves — found an electroacoustic counterpoint in Sterling’s music, transforming the viewing experience into a collective trance. Here, cinema was no longer a narrative device but a necromantic medium.

Another significant moment was the screening of Ben Rivers’ film The Sky Trembles and the Earth Is Afraid and the Two Eyes Are Not Brothers (2015), presented this past April. Based on a short story by Paul Bowles and shot amid the desert ruins of Morocco, the film moves between ethno-fiction and metaphysical elegy. “There are stories that begin at the point where voices echo,” writes Aridjis. “Ben Rivers seems to pursue the vibration that remains when everything else has been stripped away.” In the film, vision becomes a disorientation, an initiatory journey with no return, a perceptual epiphany. Rivers does not film the afterlife, but what lingers in its shadow.

The catalogue, conceived and curated by Moretti, takes the form of an oracle-book — a collection of poetic and essayistic texts that accompanies the exhibition as its conceptual extension. Structured as a montage of voices, it brings the artists’ works into dialogue with writings by Blake, Baudelaire, Poe, Mallarmé, Donne, Goethe, and Colquhoun. The curatorial act itself becomes part of the artistic gesture: a symbolic, diagrammatic architecture composed through affinities, analogies, and unexpected resonances. In this sense, the book unfolds as a “temporal and affective rebus,” an aesthetic beyond capable of redrawing the boundaries of experience.

In an age dominated by coercive transparency and data, Hereafter claims opacity, marginality, and the irreducible. It is not a thematic exhibition: it is an invocation, a habitable semantic field, a lasting interference. As Swedenborg himself once stated, “The spiritual world is not elsewhere. It is the interior of things.”