Interview by Joana Maria —

Ahead of its online screening as part of the DEMO Moving Image Festival 2020, I’ve interviewed Ana Vaz and Tristan Bera in regards to A Film, Reclaimed (2016). The ecologic crisis is a political, economic and social crisis. It is also cinematographic, as cinema coincides historically and in a critical and descriptive way with the development of the Anthropocene. A Film, Reclaimed is a conversation, an essay that reads the terrestrial crisis under the influence and with the help of the beautiful and terrible films which have accompanied it.The following text is a result of our written exchange.

Joana Maria:In A Film, Reclaimed you establish a new condition for Humanity, uncertainty. Revisiting this work in our current state of pandemic, and amidst the rise of protests and demonstrations around the world, in line with the Black Lives Matter movement, how do you see this uncertainty now? Is it becoming more and more unavoidable and consuming, or do you find it is changing into a more concrete state of hopefulness/hopelessness?

Ana Vaz / Tristan Bera: The term “Humanity” is not employed in the film, but rather “terrestrians”. At that time, we specifically avoided the term “Humanity” as a unified, universal concept with a capital letter in order to refrain from taking the human as One, or as clearly argued by Jamaican writer Sylvia Wynter to refrain from “a conception of the human as is defined by our present ethnoclass (i.e., Western bourgeois)”[1]. Which seems to be what the contemporary civil rights movement is looking to identify and defy.

If we consider that Western history is founded on a desire for certainty through the mastery and domination of “nature”, apprehended as inextinguishable resources to exploit and extract, then, uncertainty would be an antidote to this regime. Here, uncertainty concerns the apprehension of the world, but not the world in itself. One should embrace the inexplicable and accept a state of uncertainty that can open new paradigms, before a political force starts to impose its domination. Speaking of Western and bourgeois, Virginia Woolf writes in her diaries in January 1915 during WW1, just when Western societies discover the relativity of their civilization, that “the future is somber, which is the best thing the future can be, I think.”[2] We don’t see hope as a motor in these struggles, we would refrain from calling this a hopeful time, hope is the very value that makes the system continue as it is or even return to its “normalcy” (business as usual). In abandoning hope, there is restlessness, awareness, attentiveness, consciousness raising, reclamation.

Nonetheless, in the shadow of the awakening that we are experiencing today, it becomes clear that capitalism can only continue advancing if it assumes its most radical form: fascism. Henceforth, here there is no uncertainty.

JM: The footage which you investigate offers an exposition of the Anthropocene through various different films, from author cinema to big budget movies. Moviemaking in Hollywoodesque proportions is, in itself, an industry. Looking at these excerpts I encounter both environmental critique, as well as a problem with the factory-like genesis of some big pictures that burn through a great deal of resources. Did you deliberately use found footage as an efficient and sustainable resource?

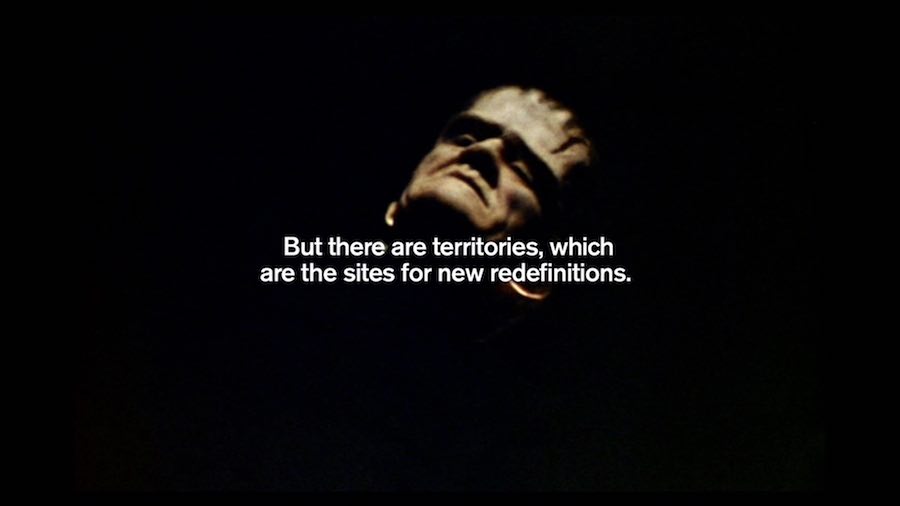

AV/ TB: The film is a meta-film as a critique of the medium. Hollywood films are the very medium of 20th century Anthropocene propaganda promoting the socio-political and economic values of the capitalist system. However, the medium has also historically revealed a precise critique of the system through its images, characters and narratives. A Film, Reclaimed weaves an audiovisual critique of our economic system through the films that metaphorically visualize it.

Often in the film, we try to reveal the monstrous unconscious of the sequences we use. It suffices to see an excerpt from John Carpenter’s They Live to visualize the forceful alienation of a system that states in subliminal Barbara Kruger-like messages: STAY ASLEEP, CONSUME, OBEY, SHOP, etc. Carpenter’s fiction of an invasion of the Earth by a cult of capitalist aliens could not be a more direct critique of “the system”. The film suggests capitalism as an alien system, a system that consistently ruptures and ravages our relationships to the earth.

And yes, our use of found footage was the foundation of the film from the beginning. We did not want to produce any images, only work with existing ones in an effort to recycle (in the sense of giving them a new cycle/new meaning) and hence reclaim the meaning of these images as critical images — a photosynthesis of sorts.

JM: You make use of French and English, and image and text through this work. As artists, filmmakers, and writers do you think there’s a hierarchy in the languages and mediums through which you express yourselves? And how did you carve an organic coexistence between all these different languages in the making of A Film, Reclaimed?

AV/ TB: The film was commissioned in 2015 by the Experimental School of Art and Politics (SciencoPo), which we were both members of, in preparation for the Paris Climate Conference. So, the use of diplomatic languages French and English was a formal strategy to address the restrictions of the climate conference rules. In this light, how not to think that this sort of international conference is already doomed to fail as the majority of parties are submitted to the linguistic rules of the major polluters?

However, in the film, as an infiltrating strategy, other languages emerge, parasite or disturb the French-English storytelling: Ana’s native Brazilian Portuguese, Thai in the excerpt of Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s opus Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives, and even other forms of communication such as the drums in The River (Jean Renoir), the buzzing of bees in Phenomena (Dario Argento), the cry of crows in Opera (Dario Argento), the growl of a gorilla in Max mon amour (Nagisa Oshima), etc. Finally, even cinema as a foreign language itself.

However, we would not say there is anything “organic” in A Film, Reclaimed but rather a highly artificial collage of images as concepts, texts as images.

JM: A last section of your film presents some utopian, yet achievable guidelines for modes of coexisting. A Film, Reclaimed is, in itself, an example of how different cultures and languages can organize and work together cooperatively. As a last exercise in clairvoyance, do you see a future for globalization where cooperation is the default work setting, and if so how would that take shape?

AV/ TB: To begin with, we mostly work with dystopian or disaster films that imply no utopian ideal, no pacific coexistence but on the contrary frictions in a fictional and political battlefield. For example: the love affair between Charlotte Rampling and a gorilla in Max mon amour, the symbiotic relationship between Jennifer Connelly and the bees in Phenomena, the tribute to the water-goddess in Uncle Boonmee…, the love-fear for Frankenstein in Spirit of the Beehive (Víctor Erice). None of these are cooperative relationships per se, but rather transgressive ones that defy the rules imposed by normative Western values. We see the last chapter of the film as a monstrous, chthonian (as philosopher Donna Haraway would suggest), ambiguous, humorous and estranged suggestion for a co-habitation that is not simple at all, one that resists the “global” or any pre-established scales used by Western modernity.

It is perhaps a world-ing of arduous work dedicated to re-building from the ashes of a collapsed world.

[1] We thank Karina Griffith for introducing the enormous work of Sylvya Wynter into our conversation.

[2] We acknowledge Vinciane Despret’s poignant reflection on the current sanitary crisis in her interview with Clémence Seurat on http://rybn.org/radioinformal/antivirus/