English text below —

“Every memory is fused with its surroundings.

Every foundation is built on something already broken.”

— Anne Michaels (Fugitive Pieces, Toronto, McClelland & Stewart, 1996, p. 140)

Entrare nello spazio di via Tadino in un pomeriggio d’autunno significa attraversare una luce che non consola. È una luce che non descrive, ma incide; che taglia la superficie e ne rivela la trama. Sulle pareti bianche della Galleria Giò Marconi, le opere di Allison Katz non si presentano come immagini, ma come sintomi: stratificazioni di tempo, materia, affezione. È una pittura che non cerca stabilità, ma vibrazione. Fin dal titolo, Foundations tradisce l’illusione di un fondamento solido. Katz non costruisce, non istituisce: scava. Le sue fondamenta non sono basi, ma fenditure; non sostegni, ma spazi porosi in cui il senso si sposta, si deforma, si ridefinisce. “Era solo questione di tempo prima che Allison Katz realizzasse Foundations,” scrive Yuval Etgar nel testo che accompagna il progetto, “una mostra che porta in primo piano il suo costante interrogarsi sul mito dell’artista e sui limiti della sua definizione come voce autonoma.”

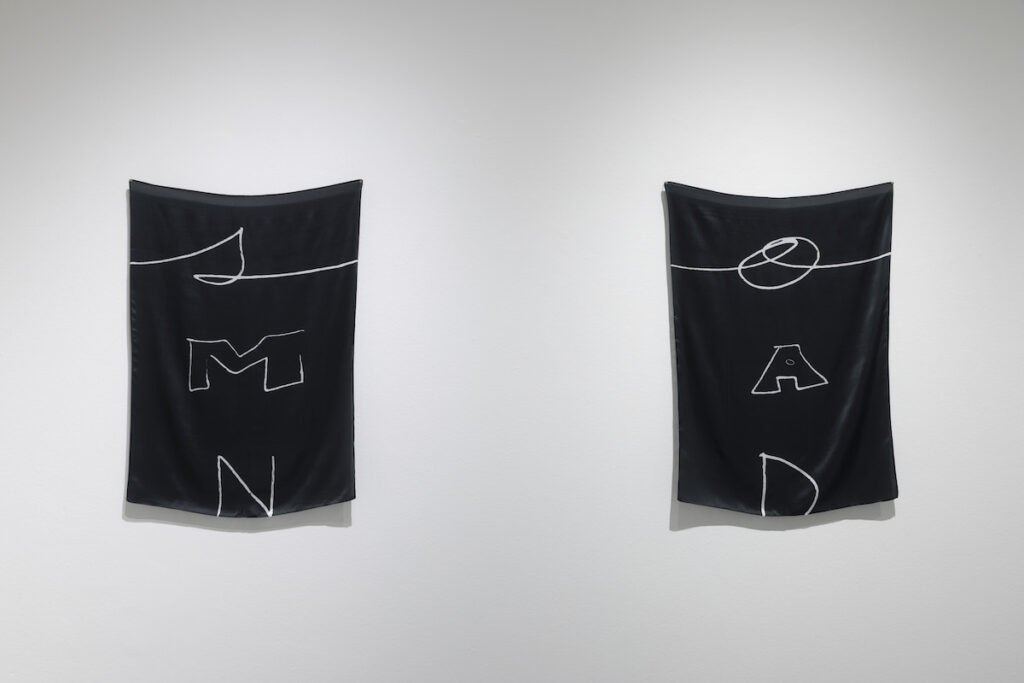

All’inizio, lo spazio si dispone come una partitura di presenze. Sulla parete d’ingresso, dodici foulard serigrafati — la Titular Suite 1–12 — compongono i nomi dell’artista, della mostra e della galleria: Allison Katz, Foundations, Gió Marconi. Le lettere, tracciate a mano in tre grafie differenti, sembrano fluttuare come segni sospesi, un alfabeto intimo che si fa tessuto. È come se il linguaggio, prima ancora di diventare parola, si incarnasse nella materia, nei fili della seta. La luce taglia le superfici, attraversando i bordi come un respiro. Ogni lettera diventa una soglia, un passaggio da un’identità all’altra: quella dell’artista, della nonna Edna Katz Silver e del gallerista stesso, che qui condivide parte della propria genealogia familiare. Niente si presenta come puro o originario. Ogni immagine porta con sé un sedimento, una vibrazione, una risonanza. Lo spazio stesso si comporta come una membrana viva, un campo di forze in cui la pittura si manifesta come eco e come presenza già abitata: un linguaggio che si costruisce nell’aria, prima di trovare la propria voce.

“Non esiste una tela bianca”, afferma Katz. “Qualcosa è sempre già presente, a partire dall’inconscio (l’ineffabile). Poi arrivano i mattoni del nostro DNA, le condizioni strutturali, i corpi delle persone amate, i fantasmi di chi non c’è più, e ogni quadro già dipinto.” Questa dichiarazione, che attraversa l’intera mostra come un filo segreto, ribadisce che ogni gesto pittorico nasce da una trama invisibile di presenze: la pittura non è mai un atto inaugurale, ma una continuazione. Katz lavora a partire da ciò che la precede — dalle genealogie biologiche e affettive fino alle immagini che la storia della pittura ha già depositato nella memoria collettiva. In questa prospettiva, Foundations diventa una meditazione sul mito dell’artista come voce autonoma, dissolvendo la figura del creatore isolato in un corpo corale di influenze e risonanze.

Katz lavora nella logica che Catherine Malabou chiama “plasticità”: la capacità di una forma di trasformarsi restando se stessa, di fondarsi nel proprio mutamento. Così la pittura diventa un corpo che si plasma nel contatto, un organismo che conserva nel gesto le sue metamorfosi. Le superfici tessute da Edna e quelle dipinte da Allison sembrano rispecchiarsi: le prime trattengono la pazienza del tempo, le seconde ne accelerano il respiro. In entrambe, la forma non si stabilizza ma pulsa, si riapre, come se l’immagine non appartenesse mai del tutto a chi la crea. Ogni pennellata si comporta come una piega, ogni colore come una resistenza: la fondazione è un atto di deformazione, un movimento che produce pensiero.

I ricami di Edna Katz Silver, novantacinquenne artista canadese, attraversano i quadri come vene vive. In essi il filo unisce e ferisce, sutura e incide. Anni fa Allison le chiese di ricamare le sue iniziali, A e K, e da quel piccolo gesto nacque un alfabeto di segni che ora ricorre in molte opere – AK (Move Over), AK (The Doors), AK (Conception) – come una lingua ereditaria, un autoritratto composto dagli altri. La pittura di Katz nasce da questa reciprocità: un corpo che si riconosce nel contatto, una forma che si trasforma senza cessare di essere sé stessa. Le trame della nonna e le pennellate della nipote si rispecchiano, la lentezza dell’una trova eco nella febbre dell’altra. Allison intreccia anche la genealogia del gallerista Gió Marconi, discendente di corniciai e produttori di tessuti. “Il profilo della cornice sono le prime quattro linee di ogni immagine,” dice. Inquadrare è sottrarre all’infinito un frammento di vita, fissarlo in una durata. Così i motivi dei foulard Bellotti, le sagome delle antiche cornici, ritornano nei dipinti come arabeschi che delimitano e aprono insieme. In Fonts (2025) il bordo del quadro diventa scrittura: otto scheletri di pesce si rincorrono come parole d’acqua, un alfabeto di ossa che ancora trattengono il respiro del mare.

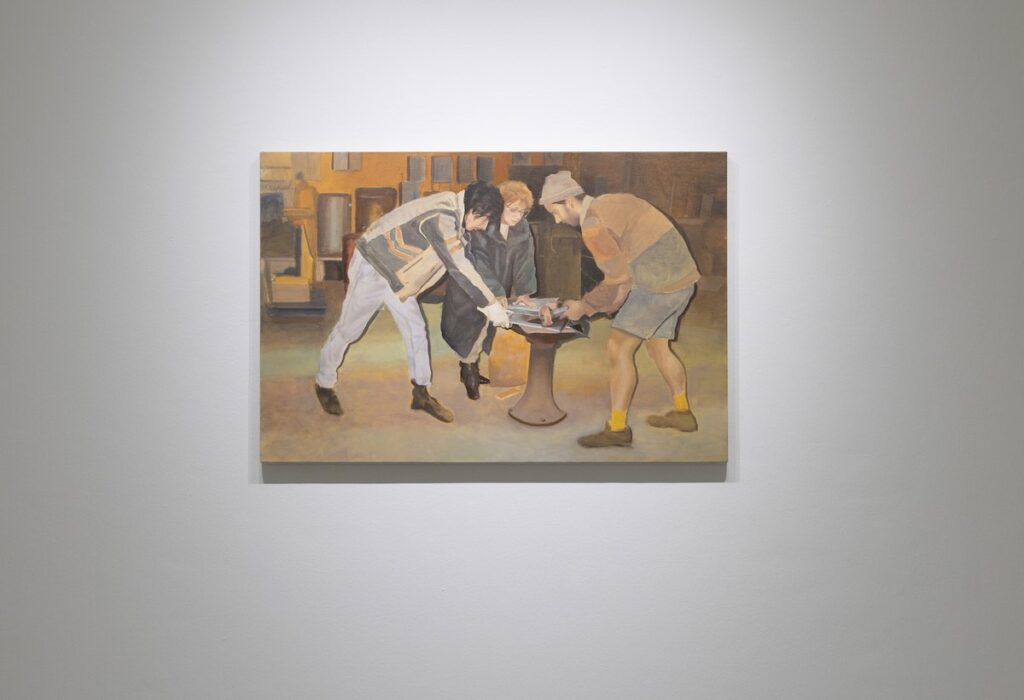

In Foundations l’origine non è mai un inizio, ma una deriva. Le tele non cercano conclusione: oscillano tra costruzione e rovina, tra densità e sparizione. La luce non spiega, sospende; trasforma ogni immagine in un passaggio, in un incontro di sguardi. In Arabesque (2025), Katz dipinge la figura del nonno paterno, ritratto a ottantasette anni mentre pattina sul ghiaccio: un’immagine inviata per posta durante il lockdown e poi trasformata in pittura. La posa — quella dell’arabesque, resa celebre dai ballerini di Degas — diventa qui il ritratto di un corpo in equilibrio precario, un esercizio di grazia senile e di genealogia affettiva. In The Foundry (2025) la nonna lavora in una fonderia di Montréal, circondata da due fabbri: la scena diventa allegoria della creazione condivisa, materia incandescente di un gesto collettivo. Anche Elevator V (Gió Marconi) (2025) parla di passaggio: l’ascensore giallo della galleria, luogo di transito e memoria, trasformato in quadro. Il fondamento, qui, non è un punto fermo ma un movimento verticale, un respiro che sale e scende nella materia.

L’arte, sembra dire Katz, non stabilisce un ordine: estrae forma dal caos. E il caos non è disordine, ma possibilità. Ogni opera è una comparsa momentanea, una figura che affiora e subito si ritrae, come una mappa tracciata sull’acqua. Fondare, per lei, significa accogliere l’instabile come condizione naturale del visibile. La galleria amplifica questa precarietà: le opere respirano insieme, si lasciano spazio, si ascoltano. Nulla procede in linea retta: la mostra si apre come un fiume che trova sempre nuovi letti. In Player (2025), un arlecchino ricavato da un foulard Bellotti si piega in una A o in una K, circondato da rane e serpenti – i nostri antenati anfibi, dice l’artista. Il collage rovescia la pittura, porta in superficie il telaio, lascia che la stoffa prenda voce.

Tutto, in Foundations, interroga il modo in cui vediamo. Katz ridistribuisce lo sguardo, allarga i confini del visibile, lascia che la pittura insegni a guardare di nuovo. Le sue fondamenta non sono individuali, ma condivise: mani, memorie, materiali che si intrecciano. In Two Gentlemen (2024), Katz lavora con suo padre, falegname: insieme costruiscono la cornice di una piccola gouache. Il legno e la pittura diventano lo stesso respiro. “Essere incorniciato: il sogno di ogni pittore,” scrive lei, e nel gesto di costruire la cornice riconosce la propria nascita. In Naviglio (2025), pensa ai canali sotterranei di Milano, ai corsi d’acqua che ancora scorrono sotto via Tadino: come radici invisibili, come la memoria che tiene in piedi la città.

Poi Lost and Found (after EKS) (2025): un ricamo perduto, ricreato in pittura, con lo stesso piccolo sonaglio d’angolo. “Found,” dice Katz, “è lavorare attraverso qualcun altro, un oggetto reso intimo dal suo smarrimento.” Il ritrovamento diventa la vera materia del dipingere. Ogni immagine contiene il rumore di altre immagini, come una conchiglia che custodisce il mare. Le fondamenta non sono pietra ma acqua, non struttura ma scorrimento.

Nell’ultima sala, AK (Conception) (2025) raccoglie l’ultimo ricamo di Edna Katz Silver: lana, seta, perle, piccoli ciondoli. La chiama la sua swan song, ma dentro quel canto c’è un inizio. Conception: il ciclo che si chiude per aprirne un altro. Accanto, Diptych (2025): due uova che si fronteggiano come specchi, un corpo maschile di spalle, desiderio e dubbio intrecciati. L’uovo, simbolo di generazione e di sguardo, contiene ancora il mondo intero.

A tratti il colore si fa fango, altrove aria. La pittura oscilla tra peso e trasparenza, tra terra e respiro. Non racconta, non spiega: lascia dietro di sé una traccia mobile. Quando si esce dalla galleria, resta una durata silenziosa, un pensiero che continua a muoversi dentro. Le fondamenta, per Katz, non sono ciò che tiene, ma ciò che cambia. Sono il gesto che passa di mano in mano, il segno che sopravvive al corpo che lo traccia. La pittura non fonda muri, apre passaggi. È una lingua che nasce da ciò che si spezza, e in quella frattura trova la propria necessità, la propria intelligenza, la propria bellezza.

Allison Katz. Foundations, Gió Marconi Gallery, Milan

“Every memory is fused with its surroundings. Every foundation is built on something already broken.” — Anne Michaels (Fugitive Pieces, Toronto, McClelland & Stewart, 1996, p. 140)

Text by Rita Selvaggio —

To enter the space on Via Tadino on an autumn afternoon is to step into a light that offers no comfort. It is a light that does not describe but inscribes; it cuts through the surface and reveals its weave. On the white walls of Gió Marconi Gallery, Allison Katz’s works do not appear as images but as symptoms—stratifications of time, matter, and affection. This is a painting practice that seeks not stability but vibration. From its very title, Foundations betrays the illusion of solidity. Katz does not build, nor does she institute: she excavates. Her foundations are not bases but fissures; not supports but porous spaces where meaning shifts, distorts, and redefines itself.

“It was only a matter of time before Allison Katz made Foundations,” writes Yuval Etgar in the accompanying text, “an exhibition that brings to the fore her ongoing questioning of the myth of the artist and of the limits of her definition as an autonomous voice.”

At first, the space arranges itself like a score of presences. On the entrance wall, twelve screen-printed scarves — the Titular Suite 1–12 — spell out the names of the artist, the exhibition, and the gallery: Allison Katz, Foundations, Gió Marconi. The letters, hand-drawn in three different scripts, seem to float like suspended signs, an intimate alphabet turned into fabric. It is as if language, even before becoming word, had incarnated itself in matter, in the silk threads. Light cuts across the surfaces, passing over the edges like a breath. Each letter becomes a threshold, a passage from one identity to another: that of the artist, of her grandmother Edna Katz Silver, and of the gallerist himself, who here shares part of his own familial genealogy. Nothing appears pure or original. Each image carries a sediment, a vibration, a resonance. The space behaves like a living membrane, a field of tensions in which painting manifests itself as echo and as an already-inhabited presence — a language built in air before it finds its voice.

“There is no blank canvas,” Katz declares. “Something is always already there — beginning with the unconscious (the ineffable). Then come the bricks of our DNA, the structural conditions, the bodies of those we love, the ghosts of those who are gone, and every painting ever made.”

This statement, which runs through the entire exhibition like a secret thread, reiterates that every painterly gesture arises from an invisible network of presences: painting is never an inaugural act but a continuation. Katz works from what precedes her — from biological and affective genealogies to the images that art history has already sedimented in collective memory. In this sense, Foundations becomes a meditation on the myth of the artist as autonomous voice, dissolving the figure of the isolated creator into a choral body of influences and resonances.

Katz works within what Catherine Malabou calls plasticity — the capacity of a form to transform while remaining itself, to find itself within its own mutation. Painting thus becomes a body shaped by contact, an organism that preserves its metamorphoses in the gesture. The surfaces woven by Edna and those painted by Allison seem to mirror one another: the former holding the patience of time, the latter quickening its breath. In both, form never settles but pulses, reopens — as if the image never wholly belonged to its maker. Each brushstroke behaves like a fold, each colour like a resistance: foundation, here, is an act of deformation — a movement that generates thought.

The embroideries of Edna Katz Silver, a ninety-five-year-old Canadian artist, run through the paintings like living veins. In them, the thread both joins and wounds, sutures and incises. Years ago, Allison asked Edna to embroider her initials — A and K — and from that small gesture an alphabet of signs was born, now recurring across many works — AK (Move Over), AK (The Doors), AK (Conception) — as an inherited language, a self-portrait composed through others. Katz’s painting springs from this reciprocity: a body that recognises itself through contact, a form that transforms without ceasing to be itself. The grandmother’s threads and the granddaughter’s brushstrokes mirror one another — the slowness of one finding its echo in the other’s fever.

Allison also interlaces the genealogy of the gallerist, Gió Marconi, descendant of picture framers and textile producers. “The profile of the frame,” she notes, “is the first four lines of every image”. To frame is to subtract a fragment of life from infinity and hold it within duration. Thus, the motifs of the Bellotti scarves, the outlines of antique frames, return in her paintings as arabesques that both enclose and open.

In Fonts (2025), the edge of the painting becomes a script: eight fish skeletons chasing one another like words made of water, an alphabet of bones that still hold the sea’s breath.

In Foundations, origin is never a beginning but a drift. The canvases seek no resolution: they oscillate between construction and ruin, between density and disappearance. Light does not explain; it suspends — turning each image into a passage, an encounter of gazes. In Arabesque (2025), Katz paints her paternal grandfather, portrayed at eighty-seven, skating on ice — a photograph sent by post during lockdown and later transposed into paint. The pose — that of the arabesque, immortalised by Degas’s dancers — becomes here the portrait of a body in precarious balance, an exercise in senile grace and affectionate genealogy.

In The Foundry (2025), her grandmother works in a Montréal foundry, surrounded by two blacksmiths: the scene becomes an allegory of shared creation, the molten matter of a collective gesture. Elevator V (Gió Marconi) (2025) too speaks of passage: the gallery’s yellow elevator — a place of transit and memory — transformed into painting. Foundation, here, is no longer a fixed point but a vertical motion, a breath rising and falling through matter.

Art, Katz seems to suggest, does not establish order — it draws form out of chaos.

And chaos, here, is not disorder but possibility. Each work is a momentary apparition, a figure that surfaces and immediately recedes, like a map traced upon water. For her, building foundations means welcoming the unstable as a natural condition of the visible. The gallery amplifies this fragility: the works breathe together, grant each other space, listen to one another. Nothing unfolds in a straight line; the exhibition opens like a river finding ever new beds.

In Player (2025), a harlequin cut from a Bellotti scarf bends into an A or a K, surrounded by frogs and snakes — “our amphibian ancestors,” as the artist calls them. Collage overturns painting, bringing the frame to the surface, letting the fabric speak.

Everything in Foundations questions how we see. Katz redistributes the gaze, expands the boundaries of the visible, lets painting teach us how to look again.

Her foundations are not individual but shared — hands, memories, materials intertwined. In Two Gentlemen (2024), Katz works with her father, a carpenter: together they build the frame of a small gouache. Wood and paint become the same breath. “To be framed — the dream of every painter,” she writes, and in the act of constructing the frame she recognises her own beginning.

In Naviglio (2025), she evokes Milan’s underground canals, the watercourses that still flow beneath Via Tadino — like invisible roots, like the memory that upholds the city. Then Lost and Found (after EKS) (2025): a lost embroidery, remade in paint, with the same tiny bell sewn to one corner. “Found,” Katz notes, “is working through someone else — an object made intimate by its loss.”

Finding becomes the true matter of painting. Every image contains the sound of others, like a seashell that holds the sea. Foundations, here, are not stone but water; not structure but flow. In the final room, AK (Conception) (2025) gathers Edna Katz Silver’s last embroidery — wool, silk, pearls, small charms. She calls it her swan song, yet within that song there is a beginning. Conception: a cycle closing only to open another. Beside it, Diptych (2025): two eggs facing each other like mirrors, a male body seen from behind, desire and doubt entwined. The egg, symbol of generation and of vision, still contains the entire world.

At times, colour thickens into mud; elsewhere, it turns to air. Painting moves between weight and transparency, between earth and breath. It neither narrates nor explains; it leaves behind a moving trace.

When one leaves the gallery, what remains is a silent duration, a thought still moving within. For Katz, foundations are not what holds, but what changes. They are the gesture that passes from hand to hand, the sign that survives the body that traced it.

Painting does not build walls — it opens passageways.

It is a language born from what breaks, and within that fracture it finds its own necessity, its own intelligence, its own beauty.