English version below

Sara Benaglia + Mauro Zanchi: Come è nato il tuo interesse per le fotografie di fantasmi e in che modo questa ricerca ha gettato le basi per i tuoi lavori successivi?

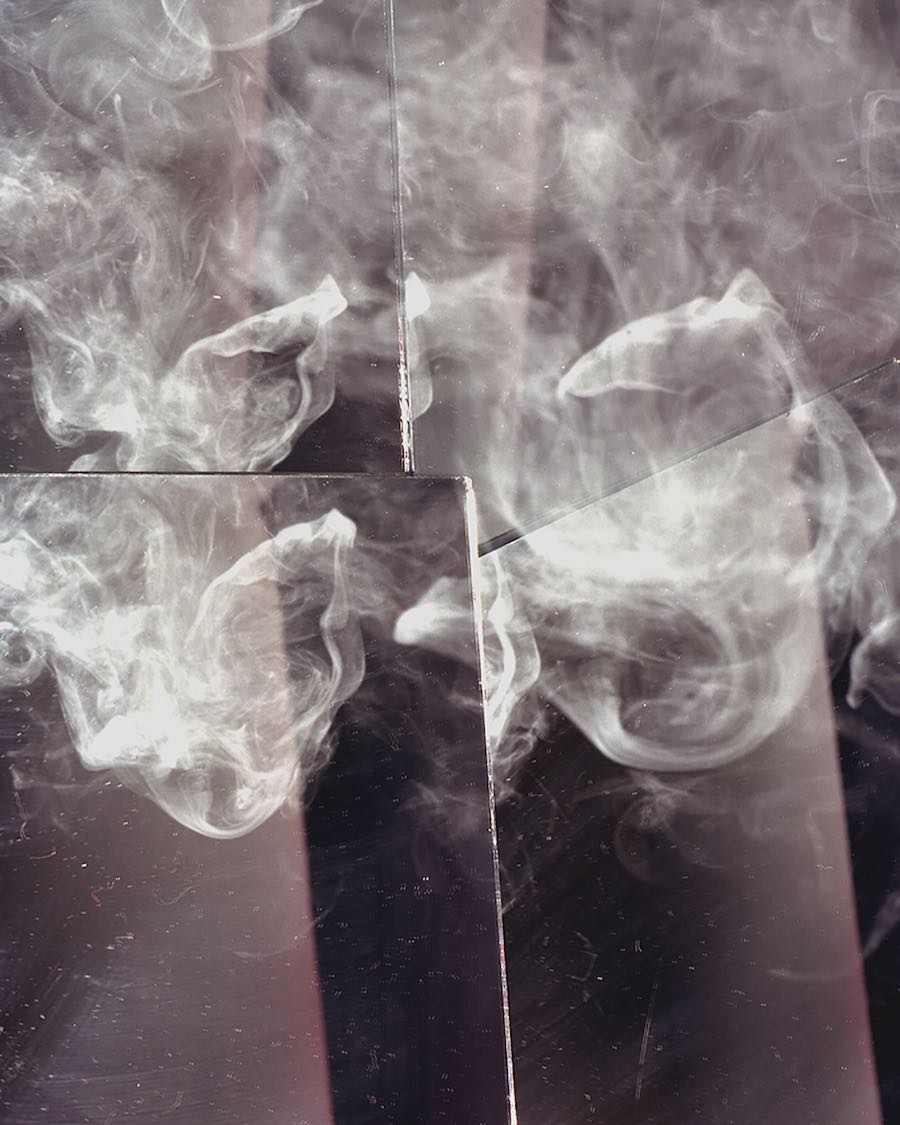

Eileen Quinlan: Ho iniziato a pensare alla fotografia di fantasmi/evidenza di spettri da bambina negli anni ’80. Ero interessata al soprannaturale in età molto giovane, forse perché sono cresciuta in una vecchia casa. Ero consapevole dei residui, i resti di vite passate. Quando ero nella scuola di specializzazione alla Columbia, nel 2003, ho iniziato a fare ricerche sulla fotografia spiritica e a scaricare immagini contemporanee di fantasmi. La fotografia spiritica all’epoca postulava che i fantasmi esistessero come nuvole ectoplasmatiche e sfere trasparenti. Il pensiero intorno all’energia spiritica nel XIX secolo, agli albori della fotografia, aveva una forma più umanoide. Mentre studiavo queste cose, ho visto un certo numero di primi dagherrotipi di fantasmi al Met qui a New York nella mostra “A Perfect Medium”, e ho iniziato a creare le mie immagini spiritiche, che si sono trasformate nella forma di fumo e specchi.

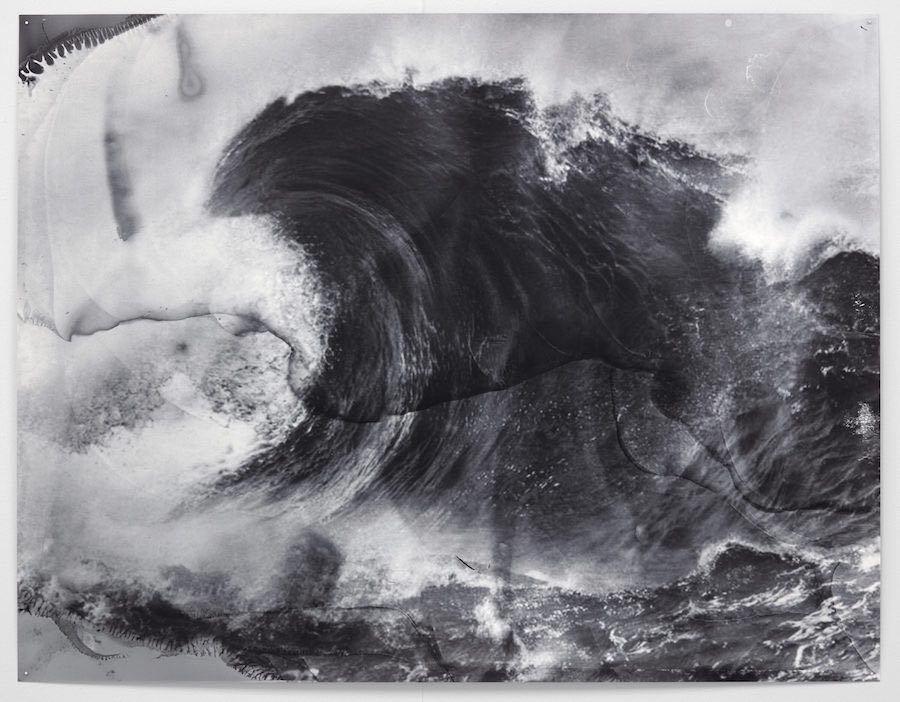

SB+MZ: Pratichi una fotografia analogica e non usi Photoshop. Quali sono i limiti e le possibilità della fotografia (luce, soggetti, ottica, chimica, byte, immagine materiale)?

EQ: Uso sia mezzi digitali sia analogici per fare fotografie. Uso Photoshop in modo molto limitato nel mio lavoro basato sullo scanner. Gli scatti su pellicola non vengono manipolati digitalmente. Questa è una domanda molto ampia, però! Non ci sono davvero limiti alla fotografia, tranne quelli che impongo a me stessa. Limito le mie attività a ciò che posso fare in studio. Uso gel colorati, tecniche commerciali e pellicole istantanee polaroid con emulsioni morbide, con cui mi piace giocare in una miriade di modi. Questo include graffiare la pellicola con chiodi e penne a sfera, agitarla in acqua con le unghie, trascinarla sulla sabbia, attaccare pezzi di pellicola bagnati insieme e staccarli quando si asciugano, sviluppare fogli di pellicola a mano usando cucchiai e pettini per pidocchi, e immergere i fogli in varie sostanze, dall’acqua marina alla tequila.

SB+MZ: Sei una fotografa di still-life? Cosa ha determinato il passaggio nel tuo lavoro da una messa in scena per la fotografia a un interesse per la fotografia come soggetto stesso?

EQ: La fotografia in sé non è il soggetto del mio lavoro. Io collaboro con materiali fotografici, ma non sto facendo un lavoro “sulla fotografia” più di quanto un pittore stia facendo dipinti sulla pittura. Il mio lavoro è femminista, interessato alla cultura materiale (come i tappetini da yoga), l’invecchiamento, la mortalità, la sessualità, la maternità, il cambiamento climatico e il collasso ambientale, la coscienza degli animali e di altri “esseri minori”, la dualità, il gemellaggio e l’identità, le conversioni spaziali dal 2D al 3D, lo spazio digitale e gli schermi, la tattilità, i modelli in natura, lo spazio interno ed esterno – un sacco di cose. Ma non riguarda la fotografia in sé. Una volta mi definivo un “fotografo di still-life”, ora queste parole sono sancite su Wikipedia. Avevo scelto questa definizione per differenziarmi dai fotografi concreti che possono effettivamente fare fotografie sulla fotografia. Il mio primo lavoro riguardava le forme, la luce e l’ombra. Pensavo al desiderio e a come funziona la seduzione nella fotografia commerciale, alla mappatura di una sorta di paesaggio psichico. Ma da molto tempo lavoro anche in altri modi.

SB+MZ: Come è entrato il femminismo nella tua pratica? Qual è la relazione tra l’autenticità dell’immagine fotografica e il femminismo?

EQ: Non sono sicuro di cosa intendiate per autenticità e di come si riferisce alla fotografia o al femminismo. Sono leggermente allergica a questo termine, in particolare quando si riferisce all’arte. Non credo che le fotografie siano autentiche se si intende che dicano la verità. E non pretenderei nemmeno che essere femminista sia maggiormente “autentico”. Il femminismo è sempre stato presente nel mio lavoro, ma nei primi tempi più astratti della mia produzione era meno evidente. Ora a volte lavoro con il mio corpo nudo, il che è più facilmente comprensibile come un atto femminista. Ciò che era femminista in ciò che facevo nei primi anni ’80 era il modo in cui le mie immagini potevano essere eseguite senza molto spazio, accesso o spesa. Molte donne fotografe storicamente hanno lavorato in interni perché si arrangiavano con un tempo limitato, come casalinghe e mezzi limitati come donne. I fotografi uomini si sono fatti carico di progetti ambiziosi che richiedevano loro di viaggiare in tutto il mondo con grandi squadre o di allestire studi elaborati e di agire come registi. Le mie prime astrazioni sono state scattate su un piccolo tavolo pieghevole usando semplici oggetti domestici. Continuo a strutturare il mio lavoro intorno ai “mezzi disponibili” e considero questo approccio sia materiale che politico.

SB+MZ: L’iconografia di Venere ha una lunga tradizione nell’arte occidentale. Nel tuo lavoro Venus Mount l’uso dello scanner continua o si scontra con questa genealogia?

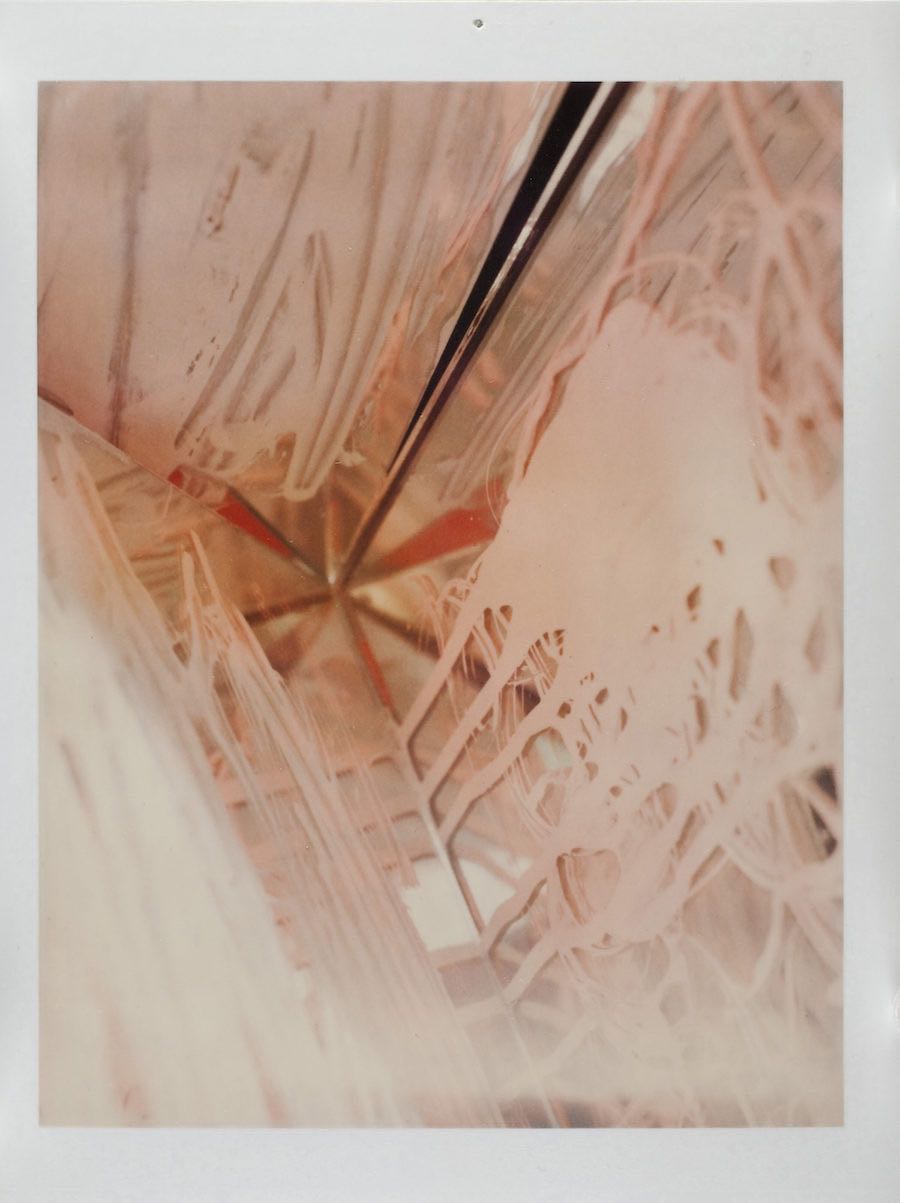

EQ: Nel “Venus Mount” generato dallo scanner il titolo si riferisce alla chiromanzia. Il monte di venere è un’area della mano che governa il romanticismo e la sessualità. L’ho imparato guardando la serie soft-core Outlander, incentrata sulle donne. Le forme triangolari che ricorrono in questo quadro si riferiscono sia al paesaggio che al sesso femminile nella sua forma più semplificata.

SB+MZ: La visione indefinita e caleidoscopica dei tuoi scatti è talvolta interrotta da piccoli dettagli del tuo studio (un’orma, un tovagliolo stropicciato). È possibile leggerli come errori di astrazione?

EQ: I blips, i mars e i tells nel mio lavoro possono essere letti come errori, certo. Possono essere intesi in molti modi. Sto cercando di interrompere il regolare transito verso la fantasia che può avvenire guardando le mie immagini. Creo l’opportunità per alcuni spettatori di uscire dal luogo della proiezione e dalle proprie riflessioni e pensare alle circostanze della genesi delle fotografie. Come sono state fatte. Chi le ha fatte. Dove sono state fatte. Forse anche perché.

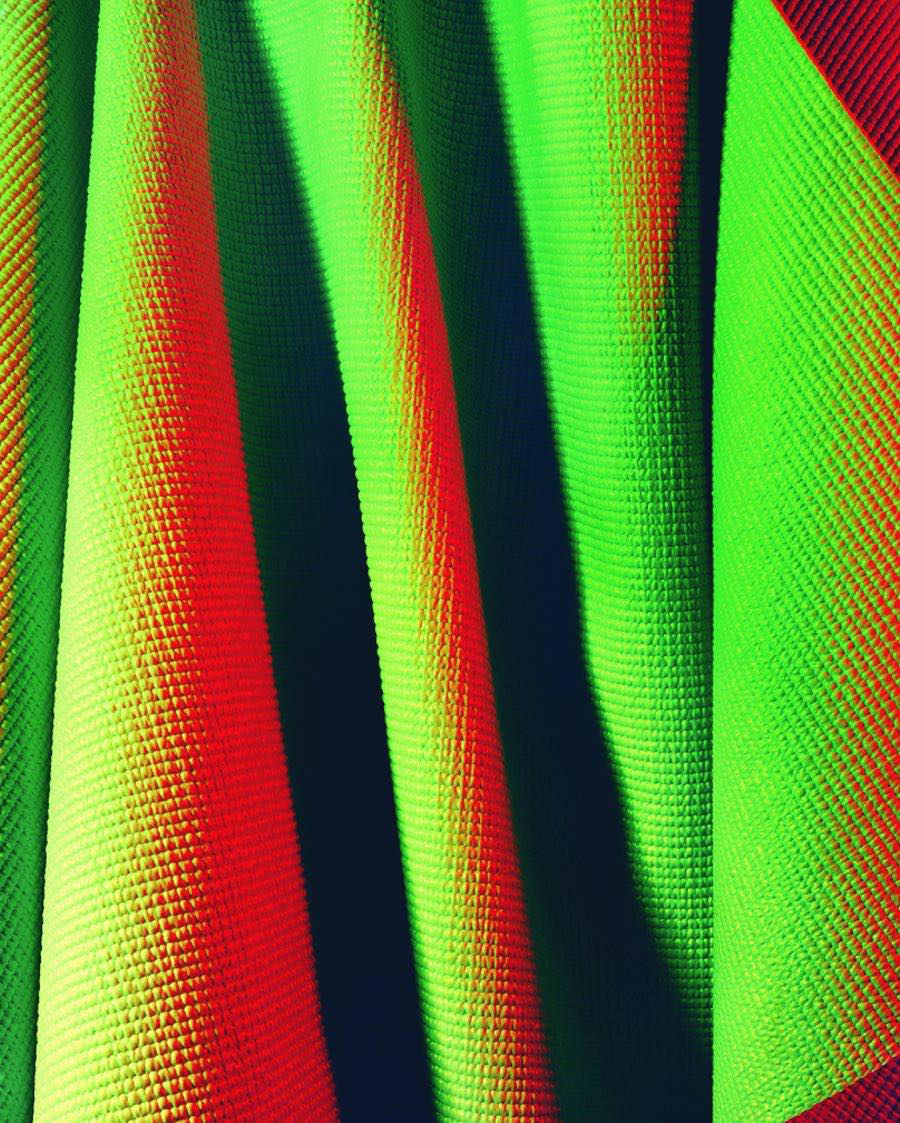

SB+MZ: Si è appena conclusa la mostra Down Dog a VISTAMARESTUDIO, in cui hai presentato il tuo percorso trasversale nel campo della fotografia astratta. Perché hai scelto questa posizione yoga come titolo della mostra?

EQ: Ho scelto “Down Dog” perché la mostra presentava una grande selezione di tappetini da yoga creati quasi un decennio fa. Quando ho scattato questo materiale pensavo all’onnipresenza dello yoga e alla crescente cultura del benessere. Volevo anche fotografare un materiale più morbido del vetro duro con cui avevo lavorato. Stavo cercando di trovare il coraggio di lavorare di nuovo con le persone. I tappetini facevano riferimento ai corpi e mi permettevano di sondare una superficie tattile. Ero stata ispirata dai piatti labiali di Judy Chicago installati in The Dinner Party, che avevo visto al Brooklyn Museum. Le mie ragioni erano concettuali e formali, personali e sociali, umoristiche e critiche. Sapevo che avevo bisogno di rimettermi in forma, entrando nella mezza età. Lo yoga mi perseguitava, così ho deciso di divertirmi un po’.

SB+MZ: Nella serie Smoke and Mirrors, cosa rappresenta per te l’accentuazione delle imperfezioni e degli errori presenti nel processo fotografico analogico?

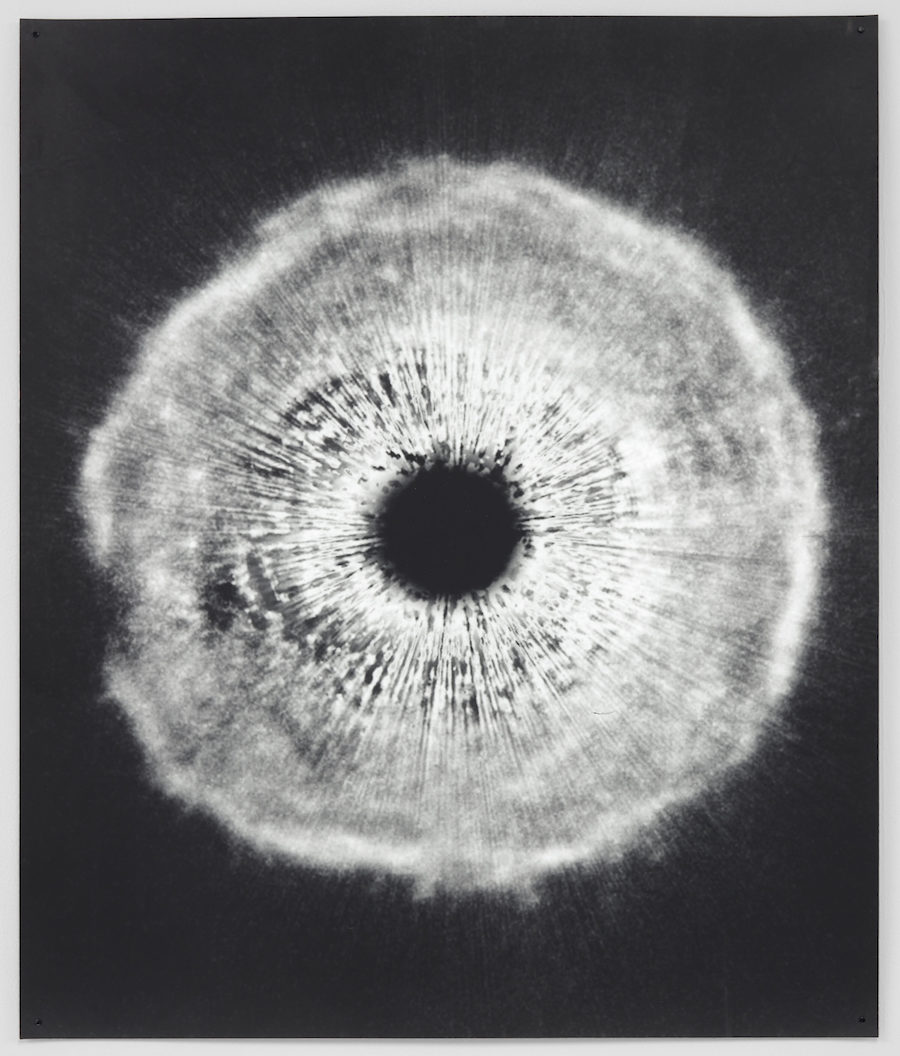

EQ: Il titolo è Smoke & Mirrors. La e commerciale è importante qui, perché questo corpo di lavoro ha molto a che fare con la fotografia commerciale e gli anni che ho passato lavorando nella moda e nella pubblicità. Il titolo con la & è più simile a un marchio. Accentuare gli errori e i miei stessi sbagli è significativo perché rende la mia presenza come autore più tangibile. E lasciare che i materiali falliscano rende anche leggibile la natura costruita di tutte le fotografie. Non sono semplici finestre ma cose scolpite dalla materia da mani umane.

SB+MZ: Cosa pensi dei fattori caso e fortuna rispetto alla loro presenza più o meno nascosta nella fotografia?

EQ: Il caso non è nascosto nella fotografia. Esso, secondo me, appare molto in superficie. Il grande “momento decisivo” di Henri Cartier-Bresson ha a che fare con il fotografo che ha i riflessi per riconoscere la sua fortuna nel momento e scattare. È vero che il caso è più difficile da esprimere nell’ambiente più controllato dello studio, ma rimane un elemento di tutti gli atti di creazione. Orchestro condizioni in cui il caso è più o meno operativo, poiché ho sviluppato un sospetto sull’espressività, in gran parte instillato dai miei insegnanti postmodernisti. Uso le procedure del caso per limitare il mio gusto e la mia sensibilità progettuale, ma non ne sono mai completamente libera. E non voglio esserlo davvero.

SB+MZ: Da dove deriva il tuo fascino (formale e concettuale) per l’astrazione?

EQ: Non lo so esattamente: dalla mia giovinezza guardando riviste e copertine di album, dai modelli di quilting amish di mia madre e mia nonna, dalla storia dell’arte, in particolare dalla pittura, e da un’attenzione alle ombre proiettate nei boschi dove sono cresciuta. Ho trascorso quasi sei dei miei vent’anni a lavorare come guardia in un museo, in gran parte in una collezione germanica, circondata da Richter, Polke, Feininger e Nolde. Da un inquieto guardare con sospetto e strizzare gli occhi alle cose, per renderle strane e desiderare di forzare mondi invisibili a manifestarsi in questo.

SB+MZ: Dove ti poni rispetto a chi, come te, ha utilizzato un mezzo (ci riferiamo alla tradizione e alla scuola di matrice astratta dei grandi pittori americani) per affinare la ‘seconda vista’ o, come scrive Wilhem Worringer in Abstraktion und Einfühlung, la ‘vista interiore’?

EQ: Non mi oppongo a questa articolazione un po’ proibita del desiderio clamoroso di un’artista di sbloccare la sua cosmologia interiore. Accedere all’eterno “autentico”. Ma so che la vista interiore è sempre informata dal mondo esterno e viceversa. Non vorrei che fosse diversamente.

New Photography | Interview with Eileen Quinlan

Sara Benaglia – Mauro Zanchi: How did your interest in ghost photographs begin and how did this research lay the foundations for your future works?

Eileen Quinlan: I started thinking about ghost photography/evidence of specters as a child in the 1980’s. I was interested in the supernatural at a very young age, maybe because I grew up in an old house. I was aware of residues, the remnants of past lives lived. When I was in graduate school at Columbia in 2003 I began researching spirit photography more and downloading images of the contemporary variety, which at the time, posited that ghosts existed as ectoplasmic clouds and transparent orbs. The thinking around spirit energy in the 19th century at the dawning of photography took a more humanoid form. While I was studying these things, I saw a number of early ghostly daguerreotypes at the Met here in NYC in the show “A Perfect Medium”, and I embarked on creating my own spirit pictures which morphed into more formal images of smoke and mirrors.

SB / MZ: Your practice analogue photography and you do not use Photoshop. What are the limits and possibilities of photography (light, subjects, optics, chemistry, bytes, material image)?

EQ: I use both digital and analogue means to make photographs. I do use Photoshop in very limited ways in my scanner-based work. The film I shoot is not digitally manipulated. This is a very broad question, though! There really aren’t any limits to photography, except for the ones I impose on myself. I limit my activities to what I can do in the studio. I use colored gels, commercial techniques, and polaroid instant films with soft emulsions that I like to play around with in myriad ways. This includes scratching the film with tacks and ballpoint pens, agitating it in water with nails, dragging it across sand, sticking wet pieces of film together and peeling them apart upon drying, developing sheets of film by hand using spoons and lice combs, and soaking the sheets in various substances from sea water to tequila.

SB / MZ: You are a still-life photographer. What determined the shift in your work from a staging for photography to an interest in photography as a subject itself?

EQ: Photography itself is not the subject of my work. I am collaborating with photographic materials, but I am not making work “about photography” any more than a painter is making paintings about paint. My work is feminist, concerned with material culture (such as yoga mats), aging, mortality, sexuality, motherhood, climate change and environmental collapse, the consciousness of animals and other “lesser beings”, duality, twinning, and identity, 2d to 3d spatial conversions, digital space and screens, tactility, patterns in nature, inner and outer space – a lot of things. But it is not about photography itself. I once called myself a “still-life photographer”, now those words are enshrined on Wikipedia. I did this as a means to differentiate myself from the concrete photographers who may indeed be making photographs about photography. My early work was concerned with shapes, light, and shadow. I was thinking about desire and how seduction functions in commercial photography, about mapping a kind of psychic landscape. But for a long time now, I’ve been working in other ways too.

SB / MZ: How has feminism entered your practice? What is the relationship between the authenticity of the photographic image and feminism?

EQ: I’m not sure what you mean about authenticity and how it relates to either photography or feminism. I’m slightly allergic to that term, particularly as it relates to art. I don’t believe that photographs are authentic if you mean that they tell the truth. And I wouldn’t claim that to be a feminist is to be more “authentic” either. Feminism was always present in my work, but in the more abstract early days of my output, it was less obvious. Now I’m sometimes working with my naked body which is more readily understood as a feminist act. What was feminist about what I was doing in the early aughts was the way my pictures could be executed with out a lot of space, access, or expense. Many female photographers historically worked indoors because they were making do with limited time as homemakers and limited means as women. Male photographers took on ambitious projects that necessitated them jetting around the globe with big teams or setting up elaborate studios and acting as directors. My early abstractions were shot on a small folding table using simple household items. I continue to structure my work around “available means” and consider this approach both material and political.

SB / MZ: The iconography of Venus has a long tradition in Western art. In your work Venus Mount does the use of the scanner continue or collide with this genealogy?

EQ: In the scanner-generated “Venus Mount” the title refers to palmistry. The venus mount is an area on the hand that governs romance and sexuality. I learned this from watching the female-centered soft-core show “Outlander”. The triangular forms that recur in this picture refer to both landscape and the female sex in its most simplified form.

SB / MZ: The undefined and kaleidoscopic vision of your shots is sometimes interrupted by small details from your studio (a footprint, a crumpled napkin). Is it possible to read them as errors of abstraction?

EQ: The blips, mars, and tells in my work can be read as errors, sure. They can be understood any number of ways. I am trying to interrupt the smooth transit to fantasy that can occur while looking at my pictures. I create opportunities for some viewers to exit the site of projection and their own musings and think about the circumstances of the photographs’ genesis. How they were made. Who made them. Where they were made. Maybe even why.

SB / MZ: The exhibition Down Dog at VISTAMARESTUDIO, in which you presented your transversal journey in the field of abstract photography, has just ended. Why did you choose this yoga position as the title for the exhibition?

I chose ”Down Dog” because the show featured a large selection of yoga mats created almost a decade ago. When I first shot this material, I was thinking about the omnipresence of yoga and a rising culture of wellness. I was also looking to photograph a softer material than the hard glass I had been working with. I was trying to get up the courage to work with people again. The mats made reference to bodies and allowed me to plumb a haptic surface. I had been inspired by Judy Chicago’s labial plates as installed in “The Dinner Party”, which I’d seen at the Brooklyn Museum. My reasons were conceptual and formal, personal and societal, humorous and critical. I knew I needed to get in shape, entering middle age. Yoga was taunting me, so I decided to have some fun with it.

SB / MZ: In the Smoke and Mirrors series, what does the accentuation of imperfections and errors that are present in the analogue photographic process represent for you?

EQ: It’s “Smoke & Mirrors”. The ampersand is important here because this body of work deals a lot with commercial photography and the years I spent working in fashion and advertising. The title with the ampersand is more like a brand name. Accentuating the errors and my own mistakes is meaningful because it makes my presence as an author more tangible. And allowing the materials to fail also renders the constructed nature of all photographs legible. They are not simple windows but things sculpted out of material by human hands.

SB / MZ: What do you think about the factors of chance and luck with regard to their more or less hidden presence in photography?

EQ: Chance is not hidden in photography. It appears, to me, very much on the surface. The grand “decisive moment” of Henri Cartier-Bresson is all about the photographer having the reflexes to recognize her luck in the moment and take the shot. It’s true that chance is harder to express in the more controlled setting of the studio, but it remains an element of all acts of creation. I orchestrate conditions where chance is more or less operative, as I have developed a suspicion of expressivity, largely instilled by my postmodernist teachers. I use chance procedures to curtail my taste and design sensibilities, but I’m never fully free of them. And I don’t really want to be.

SB / MZ: Where does your (formal and conceptual) fascination with abstraction come from?

EQ: I don’t know, exactly: from my youth looking at magazines and album covers, from my mother and grandmother’s amish quilting patterns, from art history, particularly painting, and an attentiveness to the shadows cast in the woods where I grew up. I spent almost 6 years in my early twenties working as a museum guard, largely in a Germanic collection, surrounded by Richter’s, Polke’s, Feininger’s, and Nolde’s. From a restless looking askance and squinting at things to make them strange and longing to force unseen worlds to manifest in this one.

SB / MZ: Where do you stand in relation to those who, like you, have used a medium (we are referring to the tradition and school of abstract matrix of the great American painters) to sharpen the ‘second sight’ or, as Wilhem Worringer writes in Abstraktion und Einfühlung, the ‘inner sight’?

VS: I’m not opposed to this slightly forbidden articulation of an artist’s clammy desire to unlock her inner cosmology. Accessing the “authentic” eternal. But I know that inner sight is always informed by the outer world and vice versa. I wouldn’t have it any other way.