English version below —

Sara Benaglia e Mauro Zanchi hanno intervistato TILO&TONI, il duo artistico fondato nel 2015 a Siegen, in Germania.

Sara Benaglia / Mauro Zanchi: In I’d talkely talk to them and try and get to come closer (2015) collegate la fotografia alla pittura. Qualche tempo fa ci siamo interrogati sull’idea che la fotografia possa essere scultura. Ci potete raccontare il processo che vi ha portato a questa intuizione?

TILO & TONI: Oggi le categorie di pittura, fotografia e scultura non sono più distinte come una volta. Non ci è mai importato molto se si trattasse di pittura, scultura o fotografia. Abbiamo studiato scultura nella classe di Michel Sauer, pittura con Christian Freudenberger e fotografia con Uschi Huber. E pensiamo che ciascuno di loro abbia influenzato il nostro lavoro. I’d talkely talk to them and try and get to come closer è un’installazione: la sala espositiva è rivestita di cartone nero per creare calma e per isolarla da altre influenze. L’opera è uno dei primi tentativi di collegare la fotografia alla pittura, non appendendole insieme, ma cercando di creare una sintesi. Le stampe relativamente criptiche e ombreggiate su carta baritata sono abbracciate da uno o più colori. Il titolo nasce da una citazione di una canzone pop e descrive in sostanza l’approccio attento ed esitante di questi due tipi di media. Sorprendentemente, questo passo si è rivelato più difficile di quanto inizialmente previsto e ha evocato una certa controversia. Le difficoltà sono sorte a causa del nostro profondo rispetto per le immagini. Certo, il rispetto è rimasto, ma è emerso il riconoscimento che non si devono rispettare regole quando si ha a che fare con immagini e altri tipi di media.

SB/MZ: State lavorando a LA Sunset – Ziemlich angenehmer Zustand (in corso), un progetto che si muove verso il de-meaning e che riflette l’editing delle immagini nel post-rock. Come fa una fotografia dipinta a trasformare desiderio e cliché?

T&T: Le immagini fungono da stimolo al desiderio. Le fotografie, la tecnologia di registrazione, funzionano come una rappresentazione di qualcosa di nostalgico. Fotografie di natura, albe, persone felici e/o belle, ecc. La pittura, invece, la pittura astratta, funziona in modo diverso. Si innesca attraverso la sua materialità e la sua applicazione additiva del colore – dal nulla all’immagine. La superficie, il colore, la genesi esperienziale, il colore, il gesto, il lavoro manuale, l’unicità. Tutto sembra essere vissuto, appare immediatamente. Naturalmente, la pittura ha da tempo compreso questa attribuzione di autenticità e sa come usare questa auto-riflessione e come minarla. Come un cliché, tuttavia, rimane sempre presente e gioca un ruolo nel confronto tra la fotografia mediatica e la pittura. La pittura è sempre più preziosa come oggetto, perché è in questa forma che soddisfa desideri. Di regola, la fotografia fa questo solo attraverso la sua funzione rappresentativa. Come oggetto è fondamentalmente inutile. Crediamo che il raddoppio della fotografia e della pittura sia un bene. La possibile bellezza troppo cliché, di preteso zeitgeist non vuole liberarsi dal cliché, vuole liberare il cliché stesso e prendere bastonate per il desiderio, non importa quanto sia banale. Cerchiamo di trasferire l’atteggiamento del post-rock nel fare immagini.Con riferimento a Cedric Weidmann, il post-rock non aggiunge significato all’oggetto, ma cerca di rendere l’oggetto e il significato assolutamente congruenti, di significare l’oggetto in modo tale che l’atto stesso del significato non sia spinto in primo piano – e per questo motivo deve cercare di distruggere quel surplus insito nell’opera d’arte (superare la temporalizzazione). Cerca l’impossibile, perché tutta l’arte – tutta la musica, tutto il testo e ogni immagine – trasporta un’attitudine, e perché i meccanismi della cultura borghese aggiungono successivamente la distanza. Ma ci prova; e per farlo, deve decostruire l’attitudine – il dito medio e il sogghigno dell’adolescente bianco – a favore di un contegno: di una decostruzione che fa sparire l’ombra. Il post-rock non si accontenta di affliggere, di evocare, di riprodurre il desiderio, di fingere un sentimento autentico. Piuttosto, prende il desiderio come oggetto, come un cliché; un cliché che deve essere pensato, ma che deve anche essere sentito solo attraverso i cliché. Pensiamo che il mondo sia proprio strutturato così, e il post-rock lo sa bene: funziona con il cliché come oggetto, lungi dal volerlo rompere e rifrangere, senza ironia né distanza. Il post-rock mostra il desiderio; ma in arrangiamenti così irritanti che il desiderio può essere inteso in modo impossibile – si intende invece qualcos’altro, qualcosa di nuovo. Il post-rock non rappresenta l’oggetto, ma non deve nemmeno lasciarlo sciogliere nella meschinità.

SB/MZ: In Im Walde rauscht der Wasserfall (wenns net mehr rauscht è Wasser all) (2019) { trad. Nella foresta la cascata ruggisce [se non va più in fretta, l’acqua finirà]} consigliate di considerare artisti e opere d’arte come prototipi perfetti di singolarizzazione (Andreas Reckwitz). Che cos’è l’autenticità per gli artisti che fanno parte di una più ampia tradizione di appropriazione?

T&T: Diremmo che dalla cultura dell’appropriazione si evince la consapevolezza che non c’è autenticità. L’autenticità è l’idea che da qualche parte, se si scava a fondo, si trovi il fondo di qualcosa, l’originale, l’inventore, ecc. Questo desiderio si può trovare in tutti i campi della vita e più il mondo sembra artificiale e deformato, più grande diventa il desiderio. D’altra parte, quando si dissolve questo dualismo dell’autenticità e il suo opposto, c’è spazio per la realizzazione che tutto è autentico. È quello che è, e tutto è sempre in movimento. Questa consapevolezza della rilevanza della ricontestualizzazione è ciò che determina l’appropriazione. Le opere non sono mai le stesse di quelle a cui attingono.

SB/MZ: Perché avete deciso di lavorare con materiale fotografico analogico per rompere le associazioni automatiche e lavorare sull’autenticità?

T&T: Per permettere che le modalità dell’autenticità fluiscano nell’opera fin dall’inizio, abbiamo lavorato con materiale fotografico analogico. A quel tempo potevamo osservare la proliferazione virale di immagini relative a temi come il lavoro manuale, la natura, la cultura del corpo, il cibo, la vita all’aria aperta. Raccoglievamo materiale come screenshot e immagini che cercavamo sui social media e le riprendevamo con una macchina fotografica analogica dallo schermo. Inoltre, come facciamo sempre, li abbiamo combinati con le immagini dei nostri archivi. La fotografia analogica è ancora usata e vista come “il reale“, la realtà, come Roland Barthes definisce l’immagine fotografica come „perfettamente analogica alla realtà“. La presunta autenticità della fotografia analogica corrisponde esattamente alla nostra linea di domanda. Ci appropriamo del pittorialismo del XIX secolo, così come delle tecniche fotografiche sperimentali dei surrealisti: negativi graffiati, carta fotografica scaduta, solarizzazioni e pittura con la luce. Produciamo pezzi unici, abbandonandoci alla contingenza dell’esperimento, senza dubbio la doppia autenticità.

SB/MZ: Cosa fanno le immagini alle persone?

T&T: Le immagini generano verità e creano attraverso la loro immagine il mondo. Esse danno forma a noi, alla nostra visione del mondo e quindi anche al nostro modo di agire. La “svolta pittorica” proclamata nella scienza delle immagini si riferisce, tra l’altro, al fatto che le immagini non solo rappresentano il mondo, ma che il mondo è anche generato dalle immagini. Il punto decisivo per noi è che un tempo lo sentivamo come una necessità di cui ovviamente tutte le immagini sono già state fatte. Oggi ci rendiamo conto che le immagini non sono create nel vuoto, ma che sono collegate tra loro. Vogliamo mettere la conoscenza di questa rete in una pratica artistica produttiva. Vogliamo fare della miseria di un tempo una virtù e sfruttare consapevolmente e sfacciatamente le immagini esistenti. Si tratta di una produzione artistica di immagini che non proclama la “fine delle immagini” né sventola la bandiera concettuale dell’appropriazione e della citazione con un grande gesto.

SB/MZ: Summer Collection (2016) è un messaggio d’amore?

T&T: Beh, può essere visto come un messaggio d’amore. È stato l’inizio di Tilo&Toni. Abbiamo condiviso uno studio e abbiamo notato che amiamo le stesse cose. Le idee e il modo di lavorare sono ancora il fondamento della nostra pratica lavorativa. È più un messaggio d’amore alla nostra etichetta per cui lavoriamo: TILO&TONI.

SB/MZ: Che cosa celano le sequenze di fotografie in Summer Collection (2016), dove immagini simili compaiono in varie sequenze da quattro, con lievi spostamenti e rapporti ritmico-visuali?

T&T: L’estetica dell’indifferenza e la differenza minima ci hanno sempre interessato. Cose molto simili, ma diverse nei dettagli. La cosa bella è che più piccola è la differenza, meglio si può confrontare. Questo ti costringe a fare dei confronti reciproci, a leggerlo con precisione. Si può naturalmente fare riferimento alla musica minimale o a pittori come Robert Ryman. Ma si trovano anche storie meravigliose come la conversazione tra il tassista Helmut e il passeggero Yoyo su un berretto invernale nell’episodio newyorkese di Jim Jarmusch’s Night on Earth. Helmut dice che indossiamo lo stesso berretto, Yoyo invece, che lo prende più precisamente dice: “No, il mio è diverso, il mio è da hype”.

SB/MZ: Abbiamo trovato molto interessante la presenza orizzontale, quasi un fregio che pare un lungo tubo metallico di Summer Collection – Hit em up. Cosa rappresenta per voi?

T&T: Questo lavoro è stato realizzato per una mostra che abbiamo allestito presso la nostra università per mostrare per la prima volta „Summer Collection“. Nella nostra università abbiamo scoperto uno spazio in cemento con molte lampade al neon e un lungo tubo metallico per il sistema di ventilazione. Stavamo pulendo lo spazio, abbiamo messo tutte le macchine e i rifiuti in un angolo e abbiamo dovuto nasconderli in qualche modo. Ci piace pensare alle immagini come a cose reali, così abbiamo costruito un enorme muro di cemento alla maniera di Tilo&Toni: scattando una foto da un muro, compreso il tubo, duplicandola a 10 x 2,5m e stampandola per installarla, come una specie di tenda. Più tardi, quando siamo stati invitati a mostrare i lavori al Kunstraum Düsseldorf, abbiamo pensato di portare il nostro muro nello spazio. Ma alla fine, durante l’installazione abbiamo notato che non ha bisogno delle opere in cima, ma che è un’opera autonoma.

SB/MZ: Come utilizzate le photo trouvée nella costruzione di una vostra reinterpretazione dei soggetti? Ci riferiamo per esempio al progetto Im Walde rauscht der Wasserfall (wenns net mehr rauscht is Wasser all). E nell’allestimento come fate dialogare una fotografia con un‘altra che è posta accanto, nel rapporto di vicinanza, che inevitabilmente induce a collegarle?

T&T: Come probabilmente ogni artista, anche noi da studenti ci siamo chiesti quale immagine avremmo potuto ancora fare, quale contributo ci saremmo ancora potuti permettere. Dalla questione di cosa possiamo aggiungere, è scaturita la questione della provenienza delle immagini. Nell’esame teorico di questa domanda, formata principalmente da discorsi e teorie sul campo, così come dalle idee di intertestualità, la parentela delle immagini ci è apparsa chiara e ci ha fatto capire che non nascono in uno spazio vuoto, ma che le immagini provengono sempre da altre immagini. E questa conoscenza viene presa in considerazione nei nostri rapporti con le immagini. Ci appropriamo delle immagini e dei loro contesti pragmatici e intellettuali nella consapevolezza che le immagini derivano sempre da altre immagini e che le “nuove” immagini portano con sé il loro albero/radice familiare. Inoltre, crediamo che l’appropriazione e l’adozione dell’esistente sia una pratica quotidiana che non si limita alle immagini. Attraverso la digitalizzazione e la viralizzazione dei mondi pittorici, le immagini vivono una sorta di uguaglianza, che porta Tilo&Toni a elaborare immagini senza gerarchie e a combinarle in formati adatti a noi: non c’è distinzione tra materiale estraneo e proprio, tra pittura e fotografia, tra vecchio e nuovo, tra alto e basso, tra rappresentazione e non rappresentazione.

Ciò che è nuovo per noi è cogliere l’atteggiamento del post-rock e trasferirlo in immagini. Poter realizzare ogni potenziale immagine come artisti visivi, avere accesso a tutto ciò che esiste, è più una maledizione che una benedizione. Nella ricomposizione permanente di elementi esistenti, condita con nuove tecnologie e particelle circolanti aggiornate, nasce sempre più la sensazione di aver creato qualcosa di “nuovo”. Se si è onesti con se stessi, ci si rende conto che questo modo di lavorare rischia di produrre vino vecchio in pelli nuove. Lo studioso letterario Cedric Weidmann, co-fondatore della rivista letteraria Delirium, tra gli altri, descrive questo fenomeno, in cui contrappone la letteratura del progrock a quella del post-rock. I suoi esempi più importanti di letteratura post-rock sono i romanzi di Leif Randt.

Progrock si occupa dell’inventario esistente, delle copie, delle citazioni, delle rotture, dei contrasti, delle ironie, delle esagerazioni, delle riduzioni, ecc. Il tutto è integrato da tecnologie, tendenze e temi contemporanei. L’esperimento estetico è la modalità e l’obiettivo è la “nuova” immagine. La logica è quella del progresso lineare della storia dell’arte. E questo è il pensiero modernista. Questo è il progetto delle avanguardie storiche. La domanda è: quanto sono “nuove” queste immagini? Forse sono (solo) variazioni dell’esistente.

Il post-rock, invece, si differenzia, anche se usa anche il rock, nel suo atteggiamento! Il Post-rock ha capito che c’è sempre questo divario tra il desiderio e la realizzazione di questo desiderio. E questo è esattamente il tema del post rock, il desiderio in sé e non la sua realizzazione. Anche il post rock non è interessato ad essere autentico. Ha capito che l’autenticità è un cliché. Fondamentalmente il post-rock non ha alcuna distanza dai pezzi che usa. Gli stencil, le citazioni e i cliché sono la cosa reale. Non ha bisogno di un falso fondo, non ha bisogno di profondità. Non cerca di sviluppare nuove forme attraverso esperimenti.

La combinazione di immagini e sequenze viene fuori soprattutto quando ci troviamo in uno spazio espositivo specifico. Nel caso ideale scatenano qualcosa in noi, iniziano un dialogo, ci sorprendono e ci superano. E, naturalmente, si tratta anche di precisione, produzione, selezione e combinazione delle immagini lavora secondo categorie visive e cognitive, a volte domina l’una a volte l’altra.

SB/MZ: Dovevate fare una mostra a Ljubijana, ma il Covid ha cambiato i vostri piani per il momento. Potete darci qualche informazione su questo progetto?

T&T: L’anno scorso siamo stati invitati dal direttore del fotopub Dusan Smodej per una mostra personale nel loro grande spazio di Lubiana, che avrebbe dovuto essere inaugurata qualche settimana fa. Il nostro progetto era quello di mostrare per la prima volta il nuovo corpus di lavori. Lo spazio è una vecchia stazione di servizio e volevamo riempire il pavimento con il fieno, raccogliendo vecchi scaffali di fieno che si possono trovare ovunque in Slovenia per costruirci dei muri e utilizzarne le parti come readymade e display. Ziemlich angenehme vibes (vibrazioni piuttosto piacevoli). Ma purtroppo abbiamo dovuto cancellarlo all’ultimo minuto a causa della situazione di Covid. Ora aspettiamo che la situazione sia più tranquilla per poterci recare a Lubiana per lavorare all’installazione e avere una grande apertura.

SB/MZ: A cosa state lavorando in questo momento?

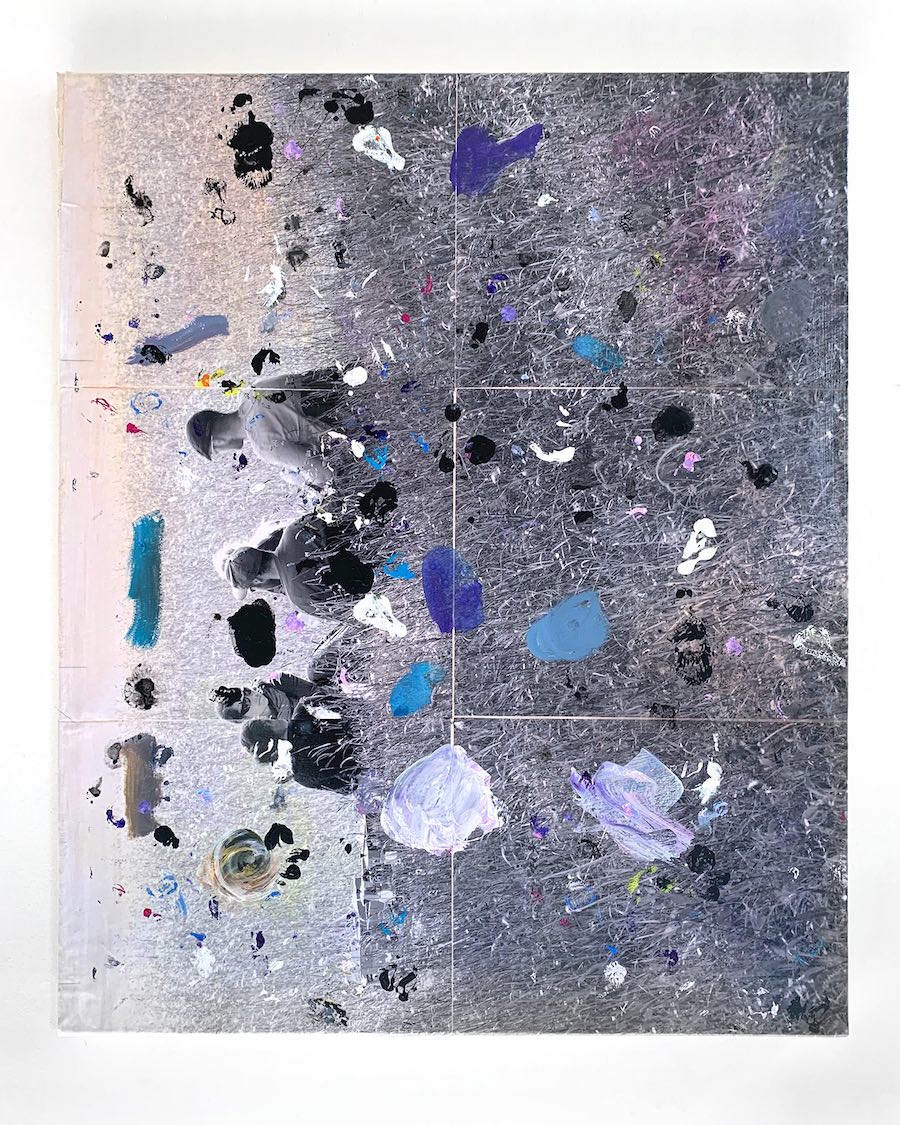

T&T: Siamo ancora in fase di sviluppo di opere che riprendono il contegno del Post-rock. Le opere presenti nel nostro studio in questo momento sono stampate su tela, stese su cornici, portate a un formato pittorico contemporaneo (190 x 130 cm) e infine completate con specifici gesti pittorici. I pensieri centrali sono l’anelito e il cliché. Il desiderio e il cliché non sono direttamente collegati? Il desiderio è sempre un cliché. Il desiderio del momento perfetto, della felicità, del partner perfetto, del sesso perfetto. E il desiderio è sempre scatenato da certe situazioni. La vista di un ampio paesaggio alla luce dell’atmosfera. Una corsa leggera con le persone giuste al posto giusto.

Come si rapportano le immagini a questo fenomeno? Weidmann scrive sul post-rock che è in questo senso che il desiderio stesso è il tema, anche se, o forse perché, sa che non può essere soddisfatto. Questo è formalizzato nel post-rock dal fatto che è molto patetico, una sorta di rievocazione dell’originalità della musica facendo musica ogni volta come la prima volta. Nella letteratura post-rock alla Leif Randt, luoghi, momenti e figure rappresentano questo desiderio. Galleggia come uno stato d’animo, come un’atmosfera al di sopra di tutto e già appare in modo impressionante nel titolo. E allora cosa succede se si usa il materiale fotografico di tutti i giorni che proviene dalla borsa delle immagini pittoriche dei nostri giorni, i social media, ed è stato selezionato secondo l’esigenza di rappresentare la rappresentazione del desiderio, e si respira la pittura in queste immagini?

Queste immagini ibride aumentano il loro potenziale di desiderio? Il cliché si dissolve in essi?

New Photography| Interview with Tilo&Toni

Sara Benaglia / Mauro Zanchi: In I’d talk nicely to them and try and get to come closer (2015) you connect photography to painting. Some times ago we were wondering around the idea that photography is sculpture… so, can you tell us about the process/ideas that took you to this intuition?

TILO & TONI: Nowadays, these categories of painting, photography and sculpture are not as distinct as they once were. We never really cared so much if it is painting, sculpture or photography. We were studying sculpture in the class of Michel Sauer and painting by Christian Freudenberger as well as photography by Uschi Huber at that time. We think they all had their influence on our work. In the end it is an installation, the exhibition room is coated with black cardboard to create calmness and to isolate it from other influences. The work is one of the first attempts trying to connect photography to painting, not by hanging them together but by trying to create a synthesis. Relatively cryptic and shady prints on baryta paper are embraced by one or several colors. The title originates from a citation of a pop song and basically it describes the careful and hesitant approach of these two types of media. Astonishingly enough, this step turned out to be more difficult than initially expected and it evoked a certain dispute. The difficulties arose due to our deep respect for the pictures. Admittedly, the respect remained but the recognition appeared that no rules must be observed when dealing with pictures and other types of media.

SB/MZ: You are actually working on LA Sunset – Ziemlich angenehmer Zustand (ongoing), a project that moves towards de-meaning and that reflects image editing in post-rock. How does a painted photograph transform the desire and cliché?

T&T: Images function as triggers of longing. Photographs, recording technology, function as a representation of something longing. Photos of nature, sunrises, happy and or beautiful people, etc. Painting on the other hand, abstract painting, works differently. It triggers through its materiality and its additive application of color – from nothing to the picture. Surface, color, experienceable genesis, color, gesture, handwork, uniqueness. Everything appears to be experienced, appears immediately. Of course, painting has since long understood this attribution of authenticity and knows how to use this self-reflectively and or to undermine it. As a cliché, however, it always remains present and plays a role in the comparison of the media photography versus painting. Painting is always more valuable as an object, because as an object it satisfies longings itself. As a rule, photography does so only through its representational function. As an object it is basically worthless. We believe that the doubling of photography and painting is good. The possible too much clichéd beauty, of claimed zeitgeist does not want to free from the cliché, it wants to free the cliché itself and take up the cudgels for longing, no matter how hackneyed it may be. We try to transfer the attitude of the post-rock to picture making.Referring to Cedric Weidmann post-rock does not add meaning to the object, but tries to make object and meaning absolutely congruent, to mean the object in such a way that the very act of meaning is not pushed into the foreground – and for this reason, it must try and destroy that surplus inherent to the work of art (surpass temporalization). It tries the impossible, because all art – all music, all text, and every picture – transports an attitude, and because the mechanisms of bourgeois culture subsequently add the distance. But it tries; and to do so, it must deconstruct the attitude – the middle finger and the sneer of the white teenage boy – in favor of a demeanour: of a de-meaning that makes the shadow disappear. Post-rock is not content with merely afflicting, evoking, or reproducing desire, with simply feigning authentic feeling. Rather, it takes desire as an object, as a cliché; a cliché that must be thought about, but must also be felt through clichés only. We think that’s just how the world is structured, and post-rock knows this – it works with the cliché as an object, far from wanting to break and to refract it, without irony nor distance. Post-rock shows desire; but in arrangements so irritating that desire can impossibly be meant itself – something else is meant instead, something new. Post-rock does not represent the object, but then it must not let it dissolve in meantness, either.

SB/MZ: In Im Walde rauscht der Wasserfall (wenns net mehr rauscht is Wasser all) (2019) { trad. Nella foresta la cascata ruggisce [se non va più in fretta, l’acqua finirà]} you suggest to consider artists and artworks as perfect prototypes of singularisation (Andreas Reckwitz). What is authenticity for artists that are part of a broader tradition of appropriation?

T&T: We would say that from the culture of appropriation speaks the realization that there is no authenticity. Authenticity is the idea that somewhere, if you dig deep, you will find a bottom of something, the original, the inventor, etc. This longing can be found in all areas of life and the more artificial and deformed the world seems, the greater the longing becomes.

On the other hand, when you dissolve this dualism of authenticity and the opposite of it, there is room for the realization that everything is authentic. It is what it is and everything is always in flux. This awareness of the relevance of re-contextualization is what makes appropriation. The works are never the same as those that tap into them.

SB/MZ: Why did you decide to work with analogue photographic material to break automatic associations and work on/against authenticity?

T&T:In order to allow the mode of authenticity to flow into the work from the very outset, we worked with analogue photographic material. At that time we could observe the viral proliferation of images relating to such themes as handiwork, nature, body culture, food, the outdoors. We were gathering material like screenshots from such images we researched on social media and shot them with an analogue camera from the screen. As well as, like we always do, combined them with images from our archives. Analog Photography is still used and seen as „the real“, the reality, as Roland Barthes defines the photographic image as „perfectly analog to reality“. The assumed authenticity of analogue photography corresponds exactly to our line of questioning. We appropriate the Pictorialism of the 19th century, as well as the experimental photographic techniques of the Surrealists: scratched negatives, expired photographic paper, solarisation and light-painting. We produce unique one-offs, giving ourselves over to the contingency of experiment – no doubt authenticity’s twin double.

SB/MZ: What do images do to people?

T&T:Images generate truth and create through their image the world. They shape us, our views of the world and thus also our way of acting. The “pictorial turn” proclaimed in the science of imagery refers, among other things, to the fact that images not only depict the world, but that the world is also generated by images. The decisive point for us is that we used to feel it as a necessity that obviously all pictures have already been made. Today we realise that the pictures are not created in a vacuum, but that they are connected to each other. We want to put the knowledge of this networking into productive artistic practice. We want to make a virtue out of the former misery and consciously and brazenly make use of the existing pictures. It is about an artistic image production that neither proclaims the ‘end of images’ nor waves the conceptual flag of appropriation and citation with a grand gesture.

SB/MZ: Is Summer Collection (2016) a love message?

T&T:Well, it can be seen as a love message. It was the very beginning of Tilo&Toni. We shared a studio and noticed that we love the same things. The ideas and the way of working is still the fundament of our working practice. It’s more a love message to our label we work for: TILO&TONI.

SB/MZ: What do the sequences of photographs in Summer Collection (2016) hide, where similar images appear in various sequences of four, with slight shifts and rhythmic-visual relationships?

T&T:The aesthetics of indifference and minimal difference have always interested us. Things that are very similar, but different in detail. The nice thing is, that the smaller the difference, the better one can compare. This forces you to make exact reciprocal comparisons, to read it precisely. One can of course refer to minimal music or to painters like Robert Ryman. But one also finds such wonderful stories as the conversation between the taxi driver Helmut and the passenger Yoyo about a winter cap in the New York episode of Jim Jarmusch’s Night on Earth. Helmut says we wear the same cap, Yoyo on the other hand, who takes it more precisely says: “No, mine is different, mine is da hype”.

SB/MZ: We found that the horizontal presence, almost a frieze that looks like a long metal tube (Summer Collection – Hit em up), is very interesting in the installation at Kunstraum Düsseldorf. What does it represent for you?

T&T:This work has been made for an exhibition we set up at our university to show „Summer Collection“ for the very first time. At our university we discovered a concrete space with many neon lamps and a long metal tube for the ventilation system. We were cleaning the space, put all the machines and rubbish in one corner and had to hide it somehow. We love to think about images as real things, so we build a huge concrete wall as Tilo&Toni is doing it: taking a picture from one wall, including the tube, duplicating it to 10 x 2,5m and printing it out to install it, as kind of a curtain. Later on, when we were invited to show works at Kunstraum Düsseldorf, we planned to bring our own wall to the space. But in the end, while installing we noticed that it doesn’t need the works on top but being an autonomous work itself.

SB/MZ: How do you use photo trouvées in the construction of your own reinterpretation of the subjects? We refer for example to the project Im Walde rauscht der Wasserfall (wenns net mehr rauscht is Wasser all). And in the installation, how do you make a photograph dialogue with another one that is placed next to it, in the relationship of proximity that inevitably leads to connecting them?

T&T:As probably every artist, as students we did asked ourselves which picture we can still make, which contribution we can still afford. From the question of what we can add, was the question of where the pictures actually come from. In the theoretical examination of this question, trained mainly in discourse and field theories, as well as the ideas of intertextuality, the kinship of the pictures became clear to us and that they did not arise in a vacuum space, but that images always come from other images. And this knowledge is taken into account in our dealings with images. We appropriate images and their pragmatic and intellectual contexts out of the awareness that images are always derived from other images and that ‘new’ images carry their family tree/ roots with them. Moreover, we believe that appropriation and adoption of the existing is an everyday practice that is not limited to images. Through the digitalization and viralisation of pictorial worlds, images experience a kind of equality, which causes Tilo&Toni to process images without hierarchies and to combine them into formats suitable for us: there is no distinction between foreign and own material, between painting and photography, between old and new, between high and low, between representation and non-representation.

What is new for us is to grasp the attitude of post-rock and to transfer it into pictures: To be able to make every potential picture as a visual artist, to have access to everything that exists, is more of a curse than a blessing. In the permanent reassembly of existing elements, spiced with new technologies and up-to-date circulating particles, the feeling of having created something ‘new’ arises again and again. If you are honest with yourself, you will realise that this way of working is in danger of producing old wine in new skins. The literary scholar Cedric Weidmann, co-founder of the literary magazine Delirium, among others, describes this phenomenon, in which he contrasts the literature of progrock with that of post-rock. His most important examples of post-rock literature are the novels of Leif Randt.

Progrock deals with the existing inventory, copies, quotes, breaks, counteracts, ironizes, exaggerates, reduces, etc. The whole is supplemented by contemporary technologies, trends and themes. The aesthetic experiment is the mode and the goal is the ‘new’ image. The logic is that of the linear progress of art history. And that is modernist thinking. That is the project of the historical avant-garde. The question is, how ‘new’ are these pictures? Perhaps they are (only) variations of the existing.

Post-rock, on the other hand, differs, although it as well uses rock, in its attitude! Post-rock has understood that there is always this gap between longing and achieving this longing. And this is exactly the theme of post rock, the longing itself and not the fulfilment of it. Postrock is also not interested in being authentic. It has understood that authenticity is a cliché. Basically post-rock has no distance to the set pieces it uses. The stencils, quotations and clichés are the real thing for it. It does not need a false bottom, no depth. It does not try to develop new forms through experiments.

The combination of images and sequences comes up mostly when we are in a specific exhibition space. In the ideal case they trigger something in us, start a dialogue, surprise and overtake us. And, of course, it is also about precision, production, selection and combination of the images works according to visual and cognitive categories, sometimes dominates the one sometimes the other.

SB/MZ: You were supposed to have a show in Ljubijana, but Covid changed you plans for the moment. Can you give us some information about this project?

T&T:Last year we were invited by the director of fotopub Dusan Smodej for a solo show at their great space in Ljubljana, which should have been opened some weeks ago. It was our plan to show the new body of work for the first time. The space is an old petrol station and we wanted to fill the floor with hay, gathering old Hayracks which can be found everywhere in Slovenia to build walls out of it and use parts as readymades and displays. Ziemlich angenehme vibes. But unfortunately we had to cancel it last minute due to the Covid situation. Now we are waiting for the situation to be more calm to be able to travel to Ljubljana working on the installation and have a great opening.

SB/MZ: What are you working on at the moment?

T&T:We are still in the process of developing works which pick up the demeanour of Post-rock. The works in our studio right now are printed on canvas, stretched on frames, brought to a contemporary painting format (190 x 130 cm) and finally completed with specific painting gestures. Central thoughts are longing and cliché. Aren’t longing and cliché directly related? Longing is always clichéd. The longing for the perfect moment, for happiness, for the perfect partner, the perfect sex. And longing is always triggered by certain situations. A view of a wide landscape in atmospheric light. A light rush with the right people in the right place. How do pictures relate to this phenomenon? Weidmann writes about post-rock that it is in this respect that longing itself is the theme, although, or perhaps because, he knows that it cannot be fulfilled. This is formalised in post-rock by the fact that it is very pathetic, a kind of reeanactment of the originality of music by making music every time like the first time. In post-rock literature alla Leif Randt, places, moments and figures represent this longing. It floats as a mood, as atmosphere above everything and already appears strikingly in the title. So what happens if one uses everyday photographic material that comes from the pictorial image purse of the present day, the social media, and was selected according to the requirement of depicting the representation of longing, and breathes painting into these pictures?

Do these hybrid pictures increase their potential of longing? Does the clichéd dissolve in them?