English version below —

Nel tempo dell’altro è una rubrica che attraversa le presenze dell’arte contemporanea nei musei storici, archeologici, universitari. Luoghi dove il tempo si stratifica e l’opera agisce come incontro, attrito o apparizione. Qui si raccontano innesti e interferenze, ascoltando ciò che resta, ciò che torna, e il silenzio che li separa.

I. Il fiato nella pietra – Ashmolean NOW e la voce muta dei calchi

“What makes the stone stony? I ask myself.

(Verso Books, 2011, p. 12)

And I think: it is the stone’s inwardness.”

— John Berger, Bento’s Sketchbook

Oxford appare come accadono i luoghi nei sogni: familiare e insieme estranea, posata nel tempo come un ricordo che non ci appartiene del tutto. Le sue strade si piegano non all’itinerario, ma alla deriva; il sapere vi è disseminato in oggetti minimi, in margini, in annotazioni non destinate a essere lette. Nulla qui è offerto con evidenza. Si avanza per allusioni, come nei libri dove le immagini sono più vere delle parole che le descrivono. Ogni edificio trattiene la traccia di una voce cancellata, ogni sala è un archivio di ciò che non è mai stato del tutto compreso. Oxford è una città scritta sulla pagina trasparente del tempo — non come una cronaca, ma come una rifrazione. È fatta di soste, di esitazioni, di quella densità rarefatta che ha il pensiero quando si avvicina al silenzio.

E forse proprio per questo l’arte qui non espone, ma si trattiene: non grida, ma ascolta.

Fondato nel 1683, l’Ashmolean Museum Oxford è il primo museo universitario al mondo aperto al pubblico. Dalla sua origine come raccolta di meraviglie naturali e artificiali, ha saputo trasformarsi nel tempo in una struttura museale che custodisce capolavori d’arte e reperti di ogni civiltà. Il museo è oggi un organismo complesso, stratificato, che ospita nelle sue sale – tra mummie egizie, dipinti di Turner, strumenti matematici medievali e manoscritti – anche una delle più insolite e toccanti collezioni dell’intero Regno Unito: la Cast Gallery, una camera della memoria scolpita nel gesso.

Si cammina tra i corpi immobili di questa galleria come se si attraversasse una notte bianca. Le statue non parlano, ma raccontano. Non guardano, ma ti leggono. Sono ombre in gesso di qualcosa che fu marmo, che fu mano, che fu pelle. Non sono originali, eppure restano più fedeli al primo respiro di chi li scolpì. Hanno attraversato i secoli come i sogni: a occhi chiusi, ma vivi. Il museo le custodisce come si fa con le ossa dei santi. Ogni calco è un fossile del gesto, un’impronta della volontà antica di toccare l’eternità. Sono circa novecento, nati tra la fine dell’Ottocento e il Novecento, per educare l’occhio, per dare al pensiero occidentale un atlante visivo, una grammatica di forma e di silenzio. Come suggerisce il pensiero di Georges Didi-Huberman, l’immagine è una fenditura del tempo, un’apertura attraverso la quale passa un’emozione che non ha più nome. Qui il tempo non è lineare: è sospeso, radiale, come una breccia nel presente. Dietro l’apparente ordine enciclopedico del museo, infatti, qualcosa comincia a vibrare. Come se le sale, abituate alla quiete del gesso, sentissero arrivare un respiro nuovo. È in questa soglia tra immobilità e risveglio che nasce Ashmolean NOW, il programma che affida alla contemporaneità il compito di non interrompere il dialogo.

Gli artisti invitati non sovrascrivono le rovine: le leggono. Siedono accanto a Laocoonte, a Ercole adolescente, alla Nike che non atterra mai. Si mettono in ascolto del fiato che resta nella pietra.

Con la prima edizione di Ashmolean NOW (10 febbraio – 30 luglio 2023), dedicata a Flora Yukhnovich e Daniel Crews-Chubb, la pittura si apre come una ferita sensuale, un corpo che pulsa dentro la storia.

Yukhnovich attinge al linguaggio delle nature morte olandesi del Seicento e del Settecento — fiori un tempo simboli di virtù e di vanitas — e lo innerva di pulsione contemporanea, mescolando i toni rosso-rugiada dei petali al brivido del mostruoso, della femminilità trasgressa, della metamorfosi.

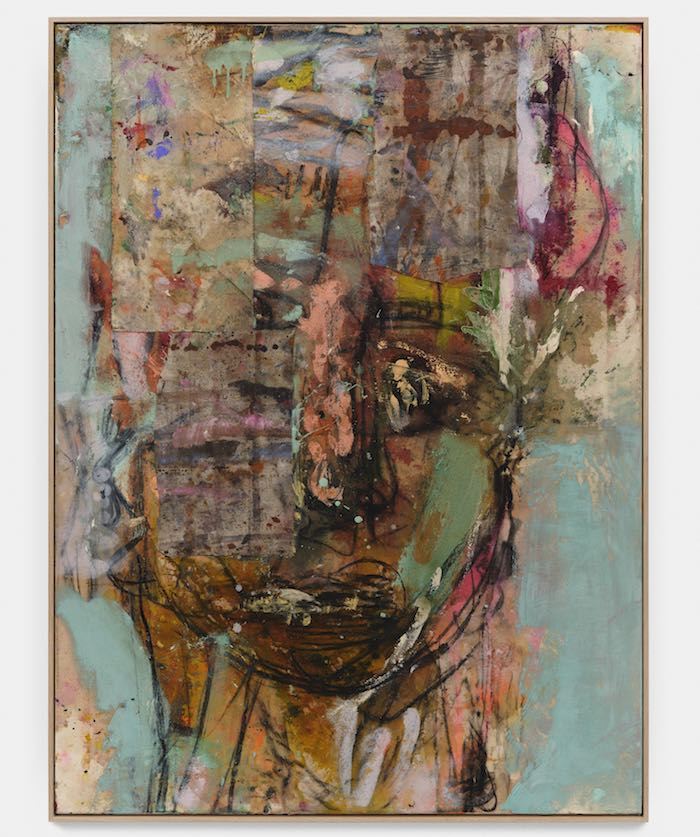

Crews-Chubb, invece, risale alle sculture antiche del museo, ai simulacri di divinità e di eroi, traducendoli in figure monumentali che corrodono la frontiera tra pittura e oggetto. Le superfici, dense di sabbia, oli e vernici, si fanno pelle, territorio di un’epopea materica.

In questo primo atto, l’Ashmolean non è più custode del passato, ma laboratorio di nuove mitologie: un incontro di epoche dove la storia si piega e si riscrive nel respiro stesso della pittura. Yukhnovich riscrive il rococò in chiave liquida e sensuale — vortici di petali, cromie domestiche che si insediano tra i gessi — mentre Crews-Chubb innesta figure totemiche, impastate di pigmenti, terra, memoria rituale. Corpi nuovi ma già antichi, figli bastardi di un pantheon in frantumi.

Poi la luce si attenua.

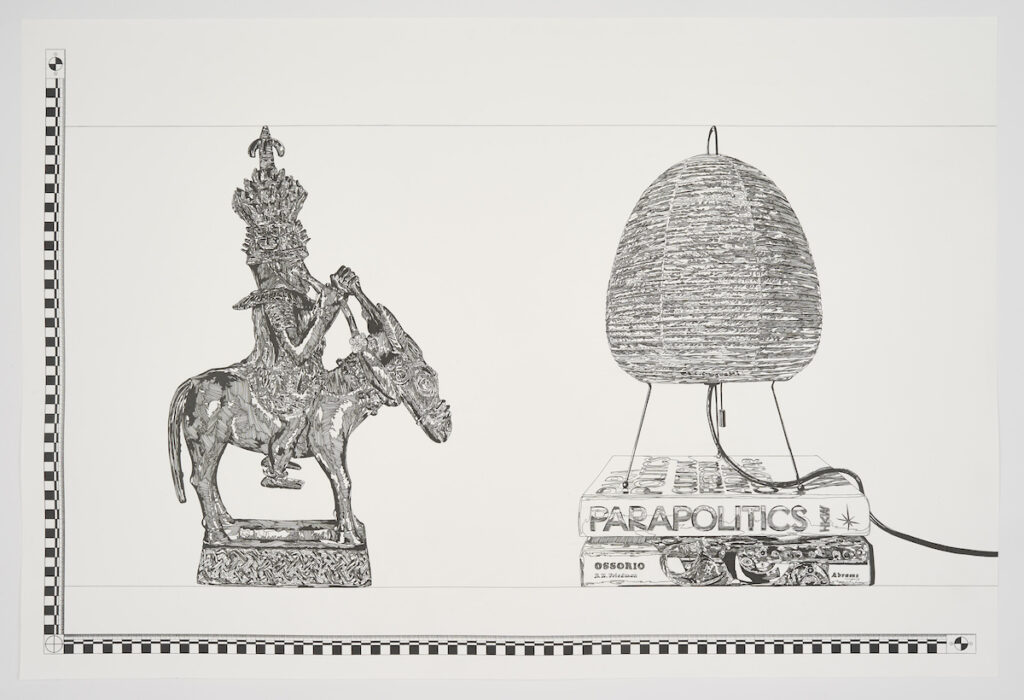

Con Pio Abad e la mostra To Those Sitting in Darkness (9 settembre 2023 – 28 aprile 2024), il museo spalanca la sua vetrina alla memoria che lacera. Il titolo — presagio e invocazione — riprende la satira di Mark Twain e restituisce al buio la sua potenza rivelatrice. In quel buio, Abad dispone oggetti, disegni, tensioni: un mantello Powhatan, tavole d’incisioni, frammenti di lutto e di geografia. È una costellazione di presenze che non cercano un posto nella storia, ma un modo per respirare ancora.

Come osserva Crystal Bennes su Frieze (16 maggio 2024), la mostra è “una meditazione lirica sulla perdita culturale e sulla possibilità di reclamare la mappatura come gesto rivoluzionario di riscrittura delle storie dell’impero”.

Abad parte proprio dal rovescio delle mappe. In I am singing a song that can only be borne after losing a country (2023) traccia con matita rossa le fenditure del retro del Powhatan’s Mantle (c. 1600–38).

È un atlante memoriale per “tutte le terre rubate che non potranno mai essere restituite”.

L’artista vi incide una cartografia del lutto, una mappa del desiderio e della perdita.

Come se la superficie della pelle potesse ancora parlare per chi è stato cancellato.

Accanto, Giolo’s Lament (2023) restituisce voce al Principe Giolo, schiavo filippino esibito in Inghilterra nel 1692. Le linee tatuate sul suo corpo, incise nel marmo rosa come vene o fiumi, disegnano una geografia dell’addio — un figlio che saluta la madre che non rivedrà mai più. Non reliquia, ma corpo che resiste al silenzio.

Sull’altra parete, la serie 1897.76.36.18.6 (2023) intreccia bronzi del Benin e oggetti domestici: una fotografia della madre, un barattolo di Nutella, un cuscino. Tra cimeli rubati e infanzie spezzate, Abad fruga negli archivi del potere e ne riscrive le faglie intime. Con collage, incisioni e disegni, ricuce le storie ferite dal colonialismo britannico, mescolando biografia e geografia, privato e politico.

Abad non ricompone: dissotterra e ricuce. I suoi lavori non chiedono di essere guardati, ma ascoltati. Non invocano giustizia, ma un’attenzione diversa — quella che si esercita quando si accetta di restare nella penombra, dove il buio diventa spazio di restituzione.

Il museo, corpo coloniale e disciplinato, si trasforma in confessionale e spiazzo, foro dell’imperialismo e della sua dissoluzione. To Those Sitting in Darkness non offre un risarcimento ma un attraversamento: un atto di contro-cartografia, un atlante della perdita che si fa canto. Come scrive Bennes, un “leggere le collezioni controcorrente può trasformare i musei — anche solo temporaneamente — in luoghi di connessione per le lotte anticoloniali”. Ed è proprio in questa tensione che l’opera di Abad trova la sua voce: nell’interferenza, nell’immaginazione, nella possibilità che l’arte, scavando nel lutto, restituisca alla storia il suo respiro umano.

E ancora, con Bettina von Zwehl e The Flood (ottobre 2024 – maggio 2025), la wunderkammer è destabilizzata. Funghi dorati, molari d’elefante, silhouette d’insetti e reperti minimi compongono un teatro silenzioso dove la meraviglia si rovescia in colpa. Le sue fotografie e installazioni non illustrano la collezione, ma ne rivelano le fratture; non mostrano, ma scuotono. Il museo vacilla — non più tempio trasparente, ma organismo vivo e compromesso.

Von Zwehl non cerca di restituire splendore all’oggetto; piuttosto lo avvicina all’oblio, lo mette in ascolto con ciò che l’ha reso possibile: l’appropriazione, il desiderio di possesso, la fascinazione per la rovina. Il suo medium non è la fotografia, ma il museo stesso, inteso come materia plastica, come memoria che rischia di dissolversi nell’acqua del tempo.

La “flood” del titolo — il diluvio — diventa metafora di un archivio sommerso che chiede di essere nuovamente abitato, non più per possesso, ma per empatia. Nei suoi ritratti ispirati ai profili medicei e alle silhouette ottocentesche, la luce diventa sostanza morale: i volti delle ragazze emergono come medaglie del presente offerte alla pazienza del passato.

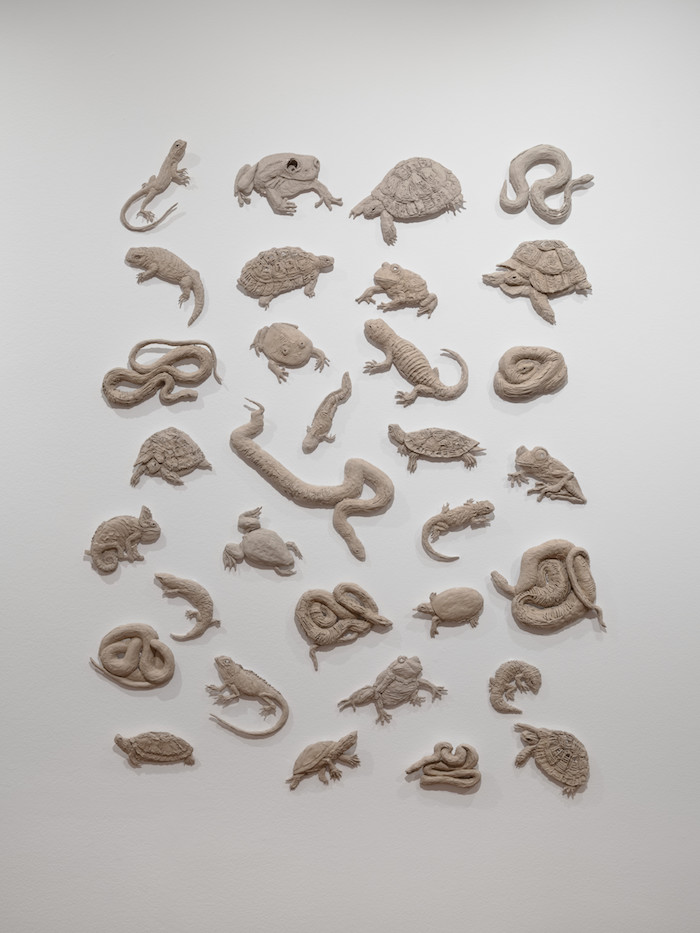

Nel quarto capitolo del programma, Daphne Wright con Deep-Rooted Things (13 giugno 2025 – 8 febbraio 2026) entra nella Cast Gallery come chi varca la soglia di una memoria: lo spazio si fa casa temporanea e archivio affettivo, luogo sospeso tra intimità e istituzione, dove la materia del quotidiano incontra l’eco della storia. In questo attraversamento, il museo sembra respirare un’altra temporalità — non più tempio, ma organismo poroso, domestico, in bilico tra la cura e la rovina.

Artista del sussurro materico, Wright dispone un frigorifero colmo, un divano abitato da figli in gesso, fiori appassiti, oggetti ordinari: l’ordinario diventa reliquia, l’intimità si fa spazio di risonanza dentro l’organismo del museo. La sua pratica, non monumentalizza, ma cura, non interrompe il silenzio della galleria — lo prolunga. Il suo è un gesto domestico esposto alla sacralità dello sguardo.

Nel lavoro di Daphne Wright, il calco non è copia ma carezza del tempo. Le sue figure dialogano con le nature morte olandesi, con la malinconia della forma che non dura. Come i figli: crescono mentre li guardi.

Il titolo stesso della mostra, tratto da un verso di W. B. Yeats — “My children may find here deep-rooted things”, della poesia The Municipal Gallery Revisited (1939) — parla di eredità, di ciò che resta per i figli anche quando tutto sembra dissolversi.

Davanti ai ritratti dei suoi amici e alle icone del nuovo stato irlandese, Yeats meditava sulla possibilità che le generazioni future trovassero, in quelle immagini, “cose profondamente radicate”: eredità emotive, morali, culturali capaci di sopravvivere al disincanto del presente. Wright raccoglie quel lascito e lo riconsegna al tempo in forma visiva, delicata, materica. Se il poeta si rivolge ai figli della nazione, l’artista guarda ai propri — scolpiti, ascoltati, accompagnati — e li pone nel cuore stesso del museo.

Le “cose profondamente radicate” non sono ideali fissi, ma emozioni trasmesse, fragilità offerte, presenze che resistono perché amate. Wright trasforma il museo in un paesaggio interiore: non luogo di certezze, ma archivio di relazioni, eco familiari, gesti che restano impressi nel gesso come in una pagina. Se per Yeats l’arte era un altare civico, per Wright è un tavolo della cucina, un frigorifero, un divano: luoghi dove il tempo si raccoglie, non si celebra. Deep-Rooted Things diventa così non solo un titolo, ma un principio poetico incarnato: la forma come cura, l’installazione come nido, la memoria come gesto materno.

Wright non impone un ordine né una gerarchia: lascia che le cose respirino nel loro stesso ritmo. Le sue forme sembrano nascere dal contatto, da una percezione incarnata che — come ricordava Merleau-Ponty — riconosce nella materia non un limite, ma un respiro. Ogni opera è un corpo che pensa, un gesto che ascolta. È in questa prossimità, nella disponibilità a lasciarsi toccare dal mondo, che affiora la sua forza: non nella durata, ma nell’attenzione, non nella forma compiuta, ma nel movimento silenzioso che la precede.

Tra Yukhnovich e von Zwehl, tra Crews-Chubb, Abad e Wright, si compone una trama di corrispondenze che non procede per capitoli ma per risonanze. Ashmolean NOW non si aggiunge al museo come un supplemento, ma lo attraversa come una corrente silenziosa, capace di riattivare il suo linguaggio nel presente. Ogni artista entra in questo dialogo come un interprete del tempo: non per riscrivere la storia, ma per misurarne la vibrazione, per restituirle un respiro.

Così l’Ashmolean, sotto la direzione di Alexander Sturgis, conferma la propria vocazione di museo in ascolto: non solo custode di ciò che è stato, ma laboratorio di ciò che può ancora accadere. Le sale, da sempre abitate da memorie antiche, si aprono ora a un ritmo più incerto, più umano: quello della percezione e dell’attesa. Non è più un luogo di certezze, ma di domande che si rinnovano ogni volta che un’opera incontra uno sguardo.

E noi, che entriamo in questo spazio, non siamo più semplici visitatori né testimoni: siamo parte di un’esperienza che ci restituisce alla lentezza, alla disponibilità a vedere di nuovo. Camminiamo tra le reliquie e le immagini come tra forme che respirano, in un tempo che si distende e si contrae, lasciandoci nel suo battito.

Non è un elogio, ma un passaggio; non una celebrazione, ma una pratica d’ascolto.

Il passato non è un archivio immobile: è una materia che si risveglia a ogni contatto, che chiede di essere toccata, riconosciuta, tradotta.

In questa sospensione, il museo si fa luogo di transito e di rivelazione — una liturgia dell’instabile, dove il sacro coincide con l’inquietudine e con la bellezza.

Ashmolean NOW non è un’interruzione, ma una continuità riflessiva. Rende il museo un dispositivo poroso, aperto, vulnerabile. Come scrive Anne Carson in Plainwater, “beauty makes me hopeless… desires as round as peaches bloom in me all night.” La bellezza non consola: inquieta, perché sopravvive anche nel vuoto, anche nel gesso. Come polvere leggera che si posa. Come eco che resta. Dove l’aura si dissolve, come insegna Walter Benjamin, sopravviene una nuova intimità: quella dell’oggetto che non pretende sacralità, ma si offre al contatto, all’interpretazione, alla ferita del tempo.

I lavori esposti nella Cast Gallery vivono questa doppia natura: presenze postume e insieme pulsanti, spettri in attesa di nuovo significato. La galleria diventa una stanza della voce interrotta, un luogo dove la materia trattiene il fiato. E NOW non è soltanto un avverbio temporale, ma un invito: a guardare ora, a restare, a sostare nel tempo del pensiero.

Il fiato resta nella pietra, e chi ascolta può sentirne il battito.

Nel dialogo tra passato e presente, tra rovina e gesto, tra voce e silenzio, il museo respira: diventa soglia dell’ignoto, luogo di rischio e rivelazione, una fragile geografia dell’instabile dove il sacro coincide con l’inquietudine e con la bellezza — un barlume di chiarità che sopravvive al naufragio.

Qui la bellezza — fragile, intermittente, luminosa — non si conserva, ma si rinnova.

E il tempo, per un istante, sembra lasciarsi sfiorare dalla grazia di chi guarda.

Cover: Ashmolean Museum © Ashmolean, University of Oxford

The Breath in the Stone

Text by Rita Selvaggio —

Oxford appears as places do in dreams: familiar yet estranged, poised in time like a memory that never wholly belongs to us. Its streets yield not to direction but to drift; knowledge is scattered among small objects, margins, and notes never meant to be read. Nothing here is given with certainty. One moves forward by allusion, as in books where the images prove truer than the words that attempt to describe them. Every building holds the trace of an erased voice, every room an archive of what was never entirely understood. Oxford is a city inscribed upon the transparent page of time — not as a chronicle but as a refraction, made of pauses and hesitations, of that rarefied density that thought acquires when it draws close to silence. And perhaps for this very reason, art here does not exhibit itself but holds back; it does not cry out — it listens.

Founded in 1683, the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford is the first university museum in the world to open its doors to the public. From its origins as a cabinet of natural and artificial wonders, it has, over time, transformed into a structure that shelters masterpieces of art and artefacts of every civilisation. Today the museum is a complex, stratified organism that houses within its rooms — among Egyptian mummies, Turner’s paintings, medieval mathematical instruments, and manuscripts — one of the most unusual and moving collections in the United Kingdom: the Cast Gallery, a chamber of memory sculpted in plaster.

One walks among the still bodies of this gallery as if crossing a white night. The statues do not speak, yet they tell stories; they do not look, yet they read you. They are plaster shadows of what was once marble, once hand, once skin. They are not originals, yet they remain closer to the first breath of the sculptor who made them. They have travelled through the centuries like dreams — eyes closed, yet alive. The museum keeps them as one keeps the bones of saints: each cast a fossil of gesture, an imprint of the ancient desire to touch eternity. Created between the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries — about nine hundred in number — they were made to educate the eye, to provide Western thought with a visual atlas, a grammar of form and of silence.

As suggested by the thought of Georges Didi-Huberman, the image is a fissure in time — an opening through which an emotion passes that no longer bears a name. Here, time is not linear but suspended, radial, like a breach in the present. Behind the museum’s apparent encyclopaedic order, something begins to tremble, as if the rooms, accustomed to the stillness of plaster, could feel a new breath approaching. It is within this threshold between immobility and awakening that Ashmolean NOW comes into being — a programme that entrusts contemporaneity with the task of not interrupting the dialogue.The invited artists do not overwrite the ruins: they read them. They sit beside the Laocoön, the adolescent Hercules, the Nike that never lands. They attune themselves to the breath that remains within the stone.

With the first edition of Ashmolean NOW (10 February – 30 July 2023), dedicated to Flora Yukhnovich and Daniel Crews-Chubb, painting opens like a sensual wound — a body pulsing within history. Yukhnovich draws on the language of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Dutch still lifes — flowers once symbols of virtue and vanitas — and infuses it with a contemporary urgency, blending the dew-red tones of petals with the tremor of the monstrous, the transgressive feminine, the metamorphic. Crews-Chubb, instead, returns to the museum’s ancient sculptures, to the simulacra of gods and heroes, translating them into monumental figures that erode the boundary between painting and object. His surfaces, dense with sand, oil and varnish, turn to skin — a terrain of material epic.

In this first act, the Ashmolean is no longer a guardian of the past but a laboratory of new mythologies: a meeting of epochs in which history bends and rewrites itself within the very breath of painting. Yukhnovich reimagines the Rococo in a liquid, sensual key — vortices of petals, domestic hues infiltrating the plaster casts — while Crews-Chubb grafts totemic figures kneaded from pigment, earth and ritual memory: new yet ancient bodies, bastard children of a shattered pantheon.

Then the light dims.

With Pio Abad and the exhibition To Those Sitting in Darkness (9 September 2023 – 28 April 2024), the museum opens its vitrines to a memory that wounds. The title — both omen and invocation — takes its cue from Mark Twain’s satire, restoring to darkness its revelatory power. Within that darkness, Abad arranges objects, drawings, tensions: a Powhatan mantle, engraved plates, fragments of mourning and geography. It is a constellation of presences that do not seek a place in history but a way to go on breathing.

As Crystal Bennes observes in Frieze (16 May 2024), the exhibition is “a lyrical meditation on cultural loss and the possibility of reclaiming mapping as a revolutionary gesture for rewriting the histories of empire.” Abad begins precisely from the reverse side of maps. In I am singing a song that can only be borne after losing a country (2023), he traces in red pencil the fissures on the back of the Powhatan’s Mantle (c. 1600–38), creating a memorial atlas for “all the stolen lands that can never be returned.” The artist engraves a cartography of mourning, a map of desire and loss — as if the surface of the skin could still speak for those who have been erased.

Nearby, Giolo’s Lament (2023) gives voice to Prince Giolo, a Filipino slave exhibited in England in 1692. The tattooed lines on his body, carved in pink marble, like veins or rivers, delineate a geography of farewell — a son bidding farewell to the mother he will never see again. Not a relic, but a body resisting silence. On the opposite wall, the series 1897.76.36.18.6 (2023) weaves together Benin bronzes and domestic objects: a photograph of the artist’s mother, a jar of Nutella, a cushion. Between looted heirlooms and broken childhoods, Abad delves into the archives of power and rewrites their intimate fissures. Through collage, engraving and drawing, he stitches back together histories torn by British colonialism, intertwining biography and geography, the private and the political.

Abad does not restore: he unearths and mends. His works do not ask to be looked at but to be listened to. They do not demand justice but a different kind of attention — the kind exercised when one consents to remain in the penumbra, where darkness becomes a space of restitution. The museum, that colonial and disciplined body, turns into both confessional and square, forum of imperialism and of its undoing. To Those Sitting in Darkness offers not compensation but passage — an act of counter-cartography, an atlas of loss that becomes song. As Bennes writes, reading collections against the grain can transform museums — even if only temporarily — into places of connection for anti-colonial struggle. And it is within this tension that Abad’s work finds its voice: in interference, in imagination, in the possibility that art, digging through grief, might restore to history its human breath.

And again, with Bettina von Zwehl and The Flood (October 2024 – May 2025), the cabinet of curiosities is unsettled. Golden fungi, elephant molars, insect silhouettes and minimal specimens compose a silent theatre where wonder turns into guilt. Her photographs and installations do not illustrate the collection but expose its fractures; they do not show, they unsettle. The museum wavers — no longer a transparent temple but a living, compromised organism. Von Zwehl does not attempt to restore the splendour of the object; rather, she draws it closer to oblivion, placing it in resonance with what made it possible in the first place: appropriation, desire, the fascination with ruin. Her medium is not photography but the museum itself — treated as plastic matter, as memory on the verge of dissolving in the water of time.

The “flood” of the title becomes a metaphor for a submerged archive that asks to be inhabited again, not through possession but through empathy. In her portraits inspired by Medici profiles and nineteenth-century silhouettes, light becomes a moral substance: the faces of young women emerge like medals of the present offered to the patience of the past.

In the fourth chapter of the programme, Daphne Wright, with Deep-Rooted Things (13 June 2025 – 8 February 2026), enters the Cast Gallery as one who crosses the threshold of a memory. The space becomes both temporary home and affective archive, suspended between intimacy and institution, where the matter of the everyday encounters the echo of history. In this crossing, the museum seems to breathe another temporality — no longer a temple but a porous, domestic organism, balanced between care and ruin.

An artist of material whisper, Wright arranges a stocked refrigerator, a sofa inhabited by plaster children, wilted flowers, ordinary objects: the everyday turns relic, intimacy becomes a chamber of resonance within the body of the museum. Her practice does not monumentalise but tends; it does not break the silence of the gallery — it prolongs it. Her gesture is domestic, yet exposed to the sacred gaze. In Wright’s work, the cast is not a copy but a caress of time. Her figures converse with Dutch still lifes, with the melancholy of a form that does not last.

Like children, they grow as you watch them.

The very title of the exhibition, taken from a line by W. B. Yeats — “My children may find here deep-rooted things,” from the poem The Municipal Gallery Revisited (1939) — speaks of inheritance, of what remains for the children even when everything seems to dissolve. Standing before the portraits of his friends and the icons of the new Irish state, Yeats reflected on the possibility that future generations might find in those images “things deeply rooted”: emotional, moral, and cultural legacies able to survive the disillusion of the present. Wright gathers that bequest and returns it to time in visual, delicate, material form. If the poet addressed “those who come after” of the nation, the artist looks to her own — sculpted, listened to, accompanied — placing them at the very heart of the museum.

The “deep-rooted things” are not fixed ideals but transmitted emotions, offered fragilities, presences that endure because they are loved. Wright transforms the museum into an interior landscape — not a place of certainties, but an archive of relationships, of familial echoes, of gestures that remain impressed in plaster as on a page. If for Yeats art was a civic altar, for Wright it is a kitchen table, a refrigerator, a sofa: places where time gathers rather than celebrates itself. Deep-Rooted Things thus becomes not merely a title but an embodied poetic principle — form as care, installation as nest, memory as maternal gesture.

Wright imposes neither order nor hierarchy: she lets things breathe in their own rhythm. Her forms seem to arise from touch, from an embodied perception that — as Merleau-Ponty reminded us — recognises in matter not a limit but a breath. Every work is a thinking body, a gesture that listens. It is in this nearness, in the readiness to be touched by the world, that her strength emerges: not in endurance, but in attention; not in the finished form, but in the silent movement that precedes it.

Between Yukhnovich and von Zwehl, between Crews-Chubb, Abad and Wright, a web of correspondences takes shape — one that advances not by chapters but by resonances. Ashmolean NOW does not add itself to the museum as a supplement, but moves through it like a quiet current, capable of reactivating its language in the present. Each artist enters this dialogue as an interpreter of time — not to rewrite history, but to measure its vibration, to return to it a breath.

Thus, under the direction of Alexander Sturgis, the Ashmolean affirms its vocation as a listening museum: not only guardian of what has been, but laboratory of what might still occur. Its rooms, long inhabited by ancient memories, now open to a rhythm more uncertain, more human — the rhythm of perception and of waiting. No longer a place of certainties, it becomes one of questions renewed each time a work meets a gaze. And we, entering this space, are no longer mere visitors or witnesses: we become part of an experience that returns us to slowness, to the availability to see again.

We walk among relics and images as through forms that breathe, in a time that stretches and contracts, leaving us within its pulse. It is not an act of praise but of passage; not a celebration, but a practice of listening. The past is not an immobile archive: it is a matter that awakens with every contact, that asks to be touched, recognised, translated.

In this suspension, the museum becomes a place of transit and revelation — a liturgy of the unstable, where the sacred coincides with restlessness and with beauty.

Ashmolean NOW is not an interruption but a reflective continuity. It renders the museum a porous, open, vulnerable organism. As Anne Carson writes in Plainwater, “beauty makes me hopeless… desires as round as peaches bloom in me all night.” Beauty does not console; it unsettles, because it survives even in emptiness, even in plaster — like a fine dust that settles, like an echo that remains. Where the aura dissolves, as Walter Benjamin teaches, a new intimacy arises: that of the object which does not claim sanctity, but offers itself to touch, to interpretation, to the wound of time.

The works displayed in the Cast Gallery inhabit this double nature: both posthumous and pulsating presences, ghosts awaiting new meaning. The gallery becomes a room of interrupted voice, a place where matter holds its breath. And NOW is not merely a temporal adverb, but an invitation — to look now, to remain, to linger within the time of thought.

The breath remains in the stone, and those who listen can feel its pulse.

In the dialogue between past and present, between ruin and gesture, between voice and silence, the museum breathes: it becomes a threshold of the unknown, a place of risk and revelation, a fragile geography of the unstable where the sacred coincides with restlessness and with beauty — a glimmer of clarity that survives shipwreck.

Here beauty — fragile, intermittent, luminous — is not preserved but renewed.

And time, for an instant, seems to let itself be touched by the grace of the one who looks.

Cover: Ashmolean Museum © Ashmolean, University of Oxford