English version below —

Fata Morgana non è una mostra sull’occulto, ma sull’arte di prestare ascolto. Fata Morgana non parla di spiriti, ma del linguaggio che essi hanno lasciato in eredità alla modernità: una lingua sotterranea, intermittente, che attraversa epoche e corpi. Curata da Massimiliano Gioni, Daniel Birnbaum e Marta Papini per la Fondazione Nicola Trussardi (fino al 3’/11), la mostra si offre come un dispositivo di ricezione, un atlante dell’invisibile in cui settantotto figure — visionarie, mistiche, artiste, autodidatte — tracciano una genealogia altra della creazione. Più di duecento opere — dipinti, film, fotografie, oggetti rituali — dialogano con le sale di Palazzo Morando, trasformando il palazzo stesso in un organismo sensibile, attraversato da memorie e presenze.

Il titolo, preso in prestito dal poema che André Breton scrisse in esilio nel 1940, è più di un riferimento letterario: è una chiave. In quelle pagine, composte mentre l’Europa bruciava, Breton affermava che “la chiave dei sogni apre la porta dei morti”. La poesia non raccontava, ma captava; non descriveva il mondo, ma tendeva l’orecchio. La mostra ne raccoglie l’eredità e la rilancia: anche qui la visione non è rivelazione ma ricezione, un modo di prestare ascolto a ciò che la storia dell’arte ha spesso silenziato — la sua parte medianica, involontaria, profetica.

I. L’orecchio di Breton

Fata Morgana prende forma dentro una costellazione che si muove tra Breton e le sue eredi spirituali: Hilma af Klint, Emma Kunz, Annie Besant, Madge Gill, Augustin Lesage, Fleury-Joseph Crépin. Figure poste ai margini del modernismo, ma capaci di farne vibrare la parte più inquieta e visionaria. Breton le chiamava “artisti medianici”: non produttori di immagini, ma canali di trasmissione. La curatela di Gioni, Birnbaum e Papini parte da qui — da un atto d’ascolto, da un orecchio teso sul secolo. Come Breton, anche loro sembrano interrogare la possibilità di un’arte che non nasca dal controllo ma dalla resa. Le opere scelte non si impongono: sussurrano. Non mostrano l’invisibile, ma ne registrano le vibrazioni.

Le grandi tele di Hilma af Klint, esposte per la prima volta in Italia, occupano il cuore della mostra come un coro silenzioso. Primordial Chaos, la serie dipinta tra il 1906 e il 1907, non inaugura l’astrazione come linguaggio, ma come rivelazione: cerchi, spirali, simmetrie cosmiche che sembrano provenire da un ordine interiore. Af Klint non dipingeva “per” sé ma “attraverso” sé: riceveva le immagini, non le inventava. Quei colori che salgono e discendono come fiotti di luce sono traduzioni di un messaggio ultraterreno, trascrizioni di energie sottili. È come se ogni forma nascesse dal respiro di qualcosa che non si vede. Dentro il silenzio del suo studio, Hilma ascolta: non l’eco del mondo, ma la voce che lo precede. Le sue spirali non cercano il cielo, lo ricordano. Ogni linea è un passo verso un’origine che non si misura nel tempo, ma nel battito di una visione e in quelle tele c’è una fede senza religione, una preghiera fatta di geometria e respiro.

La mostra amplifica questa condizione medianica. Le opere non sono disposte per scuola o periodo, ma per affinità occulte: diagrammi che dialogano con film, fotografie che rispondono a disegni automatici, reliquie che si specchiano in performance. È come se l’intera esposizione fosse organizzata secondo un principio di simpatia — non quello della storia ma dell’analogia, dove le cose si attraggono per segreta parentela.

Un montaggio per empatia più che per cronologia. Proprio in questa scelta risiede anche la sua zona di incertezza: talvolta la suggestione prevale sull’evidenza storica, ma è in questa sospensione che la mostra trova il suo respiro poetico.

Breton stesso aveva riconosciuto nella produzione di artisti autodidatti e spiritualisti, da Lesage a Crépin, una forma più pura di surrealismo. Fata Morgana ne raccoglie la lezione e la prolunga nel presente: l’arte come fenomeno di ricezione, non di espressione, e il visitatore, attraversando le sale, diventa a sua volta medium: le immagini non si guardano, si ascoltano.

In questo orizzonte la creatività non coincide più con l’invenzione ma con l’apertura. Duchamp, in un testo del 1957, lo affermava con lucidità: “L’artista agisce come un essere medianico che, dal labirinto al di là del tempo e dello spazio, cerca la via verso una radura.” È questa l’idea che anima la mostra: la creazione come evento di passaggio, un flusso che attraversa i corpi e li eccede. In questo viaggio, il percorso espositivo si dispiega per costellazioni, come un atlante di risonanze: nei “Fiori di carne” il corpo si fa preghiera e materia ardente; nelle “Voci dello spirito” la parola diventa canto e apparizione; nei “Corpi senz’organi” la forma si dissolve, trasmutando in energia e desiderio. Ogni sezione è un passaggio tra stati dell’essere, un diverso grado dell’ascolto.

II. La casa e la contessa

Se il pensiero di Breton fornisce il metodo, il corpo della mostra è la casa che la accoglie. Palazzo Morando, nel cuore del Quadrilatero, non è semplice contenitore ma strumento sensibile, un organismo capace di ricordare. Ogni sala, ogni specchio, ogni broccato sembra partecipare alla risonanza delle opere. Un tempo dimora della contessa Lydia Caprara Morando Attendolo Bolognini — nobile, teosofa e collezionista di testi proibiti — il palazzo custodisce una delle biblioteche più singolari del suo tempo: volumi di alchimia, ermetismo, spiritismo, teosofia, manoscritti dedicati al mistero e alla reincarnazione. È da questo archivio segreto che nasce Fata Morgana. La rassegna non si limita a dialogare con lo spazio: ne riattiva la memoria, riportando in superficie una storia di donne che seppero conciliare privilegio e ricerca spirituale, mondanità e desiderio di conoscenza.

La contessa Bolognini, nata ad Alessandria d’Egitto nel 1870 e morta nel 1954, rappresenta il cuore occulto della mostra. Figura di confine, oscillava tra la vita aristocratica e la passione metafisica. Nel suo salotto milanese si incontravano scienziati, artisti e iniziati; nelle sue lettere si leggono invocazioni, note di sedute spiritiche, annotazioni sulla proiezione astrale. Il suo modo di pensare la conoscenza — come attraversamento, come mediazione tra mondi — anticipa la sensibilità della mostra. Nata tra le sabbie e il mare, portava negli occhi la luce dei deserti e il chiarore elettrico delle lampade di Milano. Parlava piano, come chi teme di rompere l’aria, e la sua voce sembrava custodire nomi dimenticati. Non cercava risposte ma presenze. Credeva che ogni cosa avesse un doppio: la casa, la parola, persino il silenzio. Questa nobildonna non studiava i misteri, li abitavae attraversava il sapere come si attraversa una stanza al buio: fidandosi del tatto, del battito del cuore, della vibrazione delle cose. Tra i velluti e i ritratti, la sua figura rimane sospesa come una nota non risolta, come un lume che non si spegne, ma resta acceso nella distanza.

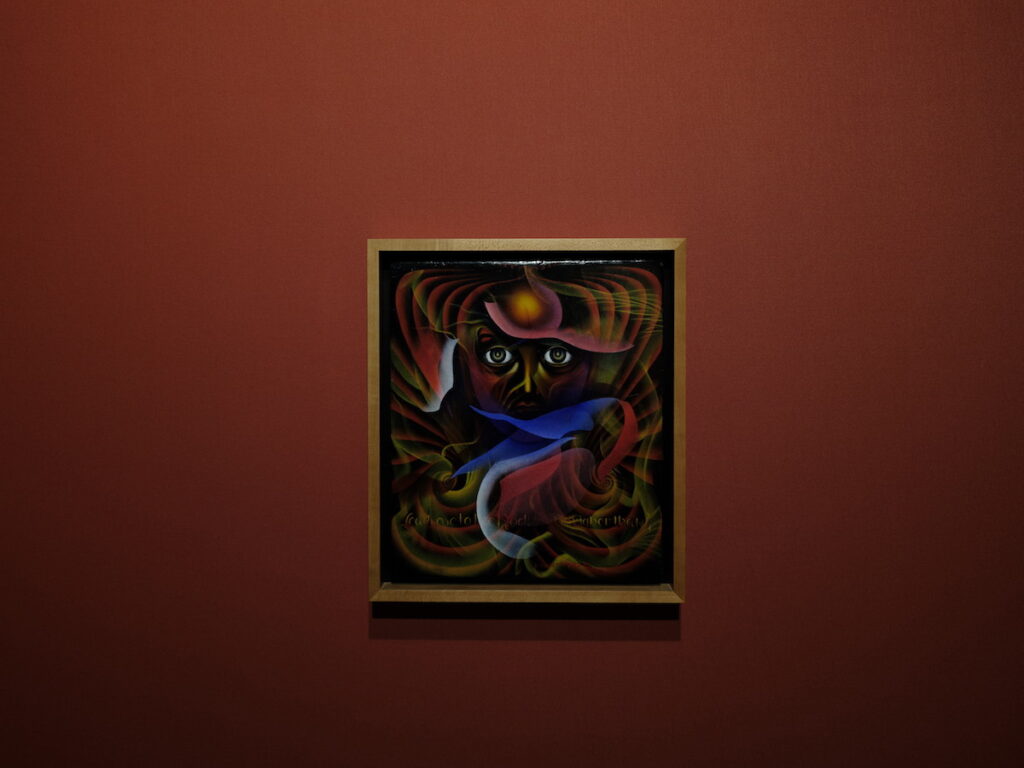

A lei fanno eco le fotografie di Linda Gazzera e Eusapia Palladino, le mani in gesso medianico provenienti dal Museo Lombroso, le carte di Fernand Desmoulin e Anna Hackel, i disegni di Aloïse e Madge Gill: opere nate da una relazione diretta con l’invisibile, da uno stato di trance o di automatismo. In ciascuna di esse, il gesto è un evento che accade al di là dell’intenzione. In questo coro di prove e apparizioni si innesta la contro-liturgia di Chiara Fumai, una partigiana della memoria. The Book of Evil Spirits (2015) non è un semplice video di repertorio: è una seduta rovesciata, una ventriloquia femminista che convoca le voci rimosse della storia per restituire loro un palco e un lessico. Fumai tratta l’“invisibile” come un archivio politico: non ciò che non si vede, ma ciò che è stato fatto tacere. Nel suo libro-rito, il medium non è un tramite neutro, accanto agli album di sedute spiritiche e ai gessi medianici custoditi negli archivi, The Book of Evil Spirits funziona come il loro negativo attivo: un dispositivo che restituisce corpo e linguaggio a chi è stato espropriato del proprio. La sua presenza segna una svolta decisiva nel percorso: la medianità smette di essere semplice trasmissione e diventa gesto di insubordinazione, una forma di parola restituita. È la stessa logica che anima la casa della contessa — biblioteca di saperi proscritti — ora riattivata come teatro dell’ascolto. In questa sezione la mostra tocca uno dei suoi vertici critici: il rischio di romanticizzare la “medianità” viene bilanciato da un uso politico del silenzio, che restituisce complessità al concetto di invisibile.

Nel percorso si avverte come la casa stessa partecipi a questo movimento. Le sale non separano le epoche: le sovrappongono. Il barocco dei soffitti accoglie i film di Maya Deren e Kenneth Anger; gli arredi settecenteschi fanno da quinta ai neon di Kerstin Brätsch; le vetrine custodiscono insieme libri antichi e frammenti di vetro contemporaneo. Tutto respira nello stesso tempo: quello della visione.

È come se la mostra avesse risvegliato il palazzo, restituendogli la sua natura di corpo medianico. Le pareti, intrise di memorie e di voci, si fanno superfici di proiezione. La contessa, che un tempo praticava la scrittura automatica come via di conoscenza, sembra ancora dettare parole a distanza, sospese tra i secoli.

Qui l’architettura diventa metafora dell’opera d’arte: un corpo abitato da presenze multiple. Ogni sala è una stanza mentale; le opere contemporanee, da Giulia Andreani a Marianna Simnett, non interrompono ma continuano il dialogo. In Conservative Ghost (Aetas Ferrea) 2024, Andreani dipinge un fantasma femminile che non è spettro ma memoria politica; Simnett, in Leda Was a Swan (2025), rielabora il mito come allucinazione digitale. In entrambe, la trance si sposta nel linguaggio tecnologico: la visione diventa algoritmo, la possessione si fa software. Dai primi segnali telegrafici ai flussi di dati contemporanei, l’invisibile cambia strumento ma non natura: continua a cercare corpi attraverso cui passare, canali in cui farsi suono, luce o codice.

Palazzo Morando si rivela così un archivio vivente, un palinsesto che collega la materia aristocratica del passato alla materia ibrida del presente. Come se la casa, nella sua eleganza sospesa, ospitasse un esperimento di reincarnazione culturale: l’anima del modernismo spirituale europeo che trova nel contemporaneo il proprio eco.

III. L’eredità dell’invisibile

La seconda metà della mostra attraversa il Novecento e giunge fino a oggi, seguendo il filo sottile che unisce misticismo e tecnologia, rituale e immagine in movimento. The Witch’s Cradle di Maya Deren (1943) e Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome di Kenneth Anger (1954-78) trasformano il cinema in un dispositivo di trance: corpi che danzano in uno spazio senza gravità, gesti che si ripetono come formule. La luce qui non illumina ma evoca, è essa stessa una forma di medianità.

Man Ray e Lee Miller, attraverso la fotografia, spingono più avanti l’esperimento surrealista: Groupe Surréaliste (Séance d’écriture automatique 1924-1980) e Robert Desnos (1925), di Man Ray, sono immagini che nascono dal caso, dalla sovrapposizione di tempo e desiderio. In esse, come nei testi di Breton, la visione è sempre un atto di ricezione, un modo di lasciar passare ciò che non si comprende. Unica Zürn, invece, trasforma la scrittura automatica in trance del corpo: le sue parole si avvolgono come serpenti d’inchiostro, diagrammi di una possessione che è insieme dolore e rivelazione. In lei, l’automatismo non è esercizio ma abbandono, un varco aperto sul limite tra linguaggio e follia.

E ancora, le immagini di Carol Rama e le ceramiche di Chiara Camoni portano la riflessione sul piano del corpo. Negli acquarelli di Rama la sessualità è rito, confessione e provocazione; in Camoni, la scultura diventa un organismo vegetale, una forma che respira. Kerstin Brätsch, con le sue vetrate policrome, riprende il linguaggio dell’alchimia trasformandolo in pittura-specchio: superfici che si accendono e si spengono come visioni, tra materia e spirito. A eco di quanto già affiorato, la voce di Chiara Fumai agisce ora come cerniera tra genealogie storiche e presente: The Book of Evil Spirits mette in cortocircuito seduta spiritica, performance e pamphlet, trasformando l’atto medianico in pratica di contro-narrazione. Se la trance surrealista esibiva l’inconscio come territorio senza padrone, Fumai ne rivela il debito: ogni voce che “parla attraverso” è anche una voce “parlata da” strutture di potere. La sua opera inscena allora una pedagogia dell’evocazione: imparare a chiamare per nome — e a far parlare — le presenze espulse dai canoni, fino a riscrivere il copione della storia. È un’azione tanto estetica quanto etica: la medianità come diritto di parola. In questa trama di voci e apparizioni, l’arte non è solo ascolto ma anche cura: un gesto taumaturgico che tenta di ricomporre la frattura del mondo. Come se, nel suo farsi visione, provasse ancora a guarire la ferita del reale — quella che unisce il dolore alla speranza, la materia al suo doppio invisibile.

Le voci femminili percorrono la mostra come un fiume sotterraneo. Dalle teosofe ottocentesche a Judy Chicago e Andra Ursuţa, la genealogia del femminile appare come una lunga trasmissione medianica. Non una storia lineare ma un flusso di resistenza: donne che hanno parlato attraverso gli spiriti per sfidare le gerarchie del sapere, e oggi parlano attraverso la tecnologia per sfidare quelle del potere.

In questo dialogo il concetto di “invisibile” si sposta: da dimensione metafisica diventa politica, da aldilà a interstizio. Le artiste contemporanee non cercano più l’oltre-vita, ma l’oltre-visione: l’immagine come strumento di attraversamento, come luogo dove il corpo può smaterializzarsi e riaffermarsi insieme.

Diego Marcon, con La Gola (2024), conclude la mostra come un requiem contemporaneo. L’animazione in CGI, sospesa tra cartoon e elegia, racconta un coro di voci che oscillano tra la carne e il codice. È un film che respira come un essere vivo e pensa come un algoritmo, dove l’oltre-vita si manifesta non come promessa ma come loop. Marcon racconta la fame che non si sazia: la voce che gusta e quella che soffre camminano una accanto all’altra, senza incontrarsi. Dentro le parole si sente il respiro del corpo, la sua resa lenta, il suo desiderio di restare. I volti sono fermi, gli occhi si muovono appena: è così che l’immagine prende fiato, come una preghiera detta sottovoce.

Nel contesto di Fata Morgana, questo film trova il suo specchio. Anche qui la realtà è un miraggio, un riflesso che inganna per mostrare la verità. Marcon posa lo sguardo lì dove la luce cede al buio: nella gola che inghiotte e nel silenzio che restituisce, nel punto in cui l’invisibile comincia a farsi carne. E come in un respiro che attraversa i secoli, affiorano le visioni di Corita Kent, Minnie Evans, Gertrude Morgan, Marian Spore Bush e Vanda Vieira-Schmidt: donne che hanno dipinto così come si prega, come si invoca la salvezza. Le loro immagini, nate dal fervore e dalla necessità, sono inni di luce e disperazione, profezie affidate al colore. Con loro, l’arte non si separa dalla fede: è il suo ultimo corpo visibile, la sua forma di sopravvivenza. Così l’invisibile, prima di dissolversi, si traduce in gesto, in preghiera, in sogno di redenzione.

Lungo il percorso, un filo di ironia attraversa le opere di Man Ray, Max Ernst e Pierre Klossowski: la consapevolezza che il sacro, per esistere, deve passare attraverso la maschera. Accanto a loro, le visioni carnali di Jill Mulleady ridipingono il martirio come trance moderna: corpi sospesi tra l’estasi e la ferita, dove la pittura diventa reliquia e apparizione insieme. Marcel Duchamp lo sapeva bene quando diceva che l’artista è un medium inconsapevole; e Carol Rama lo ribadisce, rovesciando l’idea stessa di “ispirazione” in una pratica di carne e desiderio.

IV. Epilogo: la soglia e il ritorno

Forse ogni progetto della Fondazione Trussardi contiene, più che un gesto di trasmigrazione, un atto di spossessamento: lasciare che l’arte perda i suoi confini e diventi un’esperienza collettiva di passaggio. Fata Morgana non si limita a uscire dai luoghi canonici; li trasforma dall’interno, come se Milano stessa — la città, la sua memoria, i suoi palazzi — fosse il medium di una voce più antica. In questa metamorfosi, la città appare come un corpo medianico e tecnologico insieme: città di fili elettrici e correnti sotterranee, dove la memoria convive con i circuiti, e l’incanto sopravvive nel cuore della modernità. Palazzo Morando non ospita: trattiene, risuona. È una cassa di risonanza in cui i secoli si sovrappongono, una dimora che, per un istante, sembra ricordare di essere stata un corpo.

Nella biblioteca della contessa, i volumi di Fludd, Lavater, Dionigi Areopagita e Masen non appaiono come reperti, ma come presenze in attesa di essere rilette. Le loro pagine, segnate dal tempo e dalla devozione, non offrono risposte: trattengono domande. È in quel silenzio che la mostra si chiude — e si apre di nuovo — come se ogni sapere proibito avesse bisogno di un orecchio per poter continuare a esistere.

Viviamo immersi in nuove superstizioni digitali, circondati da presenze senza corpo e da immagini che non chiedono più di essere credute. Fata Morgana restituisce a quell’oceano di simulacri un’altra temperatura: ci ricorda che l’immagine non è un codice ma una voce, e che vedere significa ancora prestare ascolto. La sua potenza non sta nello svelare l’invisibile, ma nel lasciarlo filtrare attraverso le forme, come una corrente sotterranea che continua a passare, nonostante tutto.

Così le opere si dispongono come frasi di un discorso senza fine: non una narrazione, ma un respiro comune. Ogni figura — da Hilma af Klint a Marianna Simnett, da Annie Besant a Diego Marcon — è un accento di questa lingua postuma che parla di noi più di quanto noi possiamo comprenderla. La medianità, in questa prospettiva, non è un fenomeno marginale ma una postura del pensiero: la disponibilità a farsi attraversare, a lasciare che qualcosa passi attraverso di noi.

Fata Morgana diventa allora il ritratto di un desiderio: credere non nella magia, ma nella possibilità che l’immagine custodisca ancora una porzione di verità che non ci appartiene. È un viaggio nei doppi specchi della visione — tra fede e conoscenza, memoria e profezia — che non cerca conciliazioni ma continuità.

Come scriveva André Breton in L’Amour fou (1937) — “il reale è ciò che non si lascia chiudere” — la realtà resta un varco, una soglia aperta.

È forse in questa apertura che la mostra trova la propria voce: nello spazio, fragile e cangiante, che separa la percezione dalla rivelazione, dove il sapere si fa eco e il mistero, per un istante, diventa abitabile.

Come un’eco nella biblioteca della contessa — o nel silenzio concentrico dello studio di Hilma af Klint — la mostra si richiude su sé stessa, lasciando che la visione continui a respirare nel tempo.

Fata Morgana: Memories from the Unseen | Fondazione Nicola Trussardi, Palazzo Morando, Milan

Text by Rita Selvaggio —

“Words are meteors.”

— André Breton, Fata Morgana, 1940

Fata Morgana is not an exhibition about the occult but about the art of listening, about that subtle act of attunement by which the visible begins to tremble.

It does not speak of spirits, but of the language they have left behind—a subterranean, intermittent tongue moving through epochs and bodies like a current beneath the skin of history.

Curated by Massimiliano Gioni, Daniel Birnbaum, and Marta Papini for Fondazione Nicola Trussardi, the exhibition unfolds as a listening device, an atlas of the unseen where seventy-eight figures—visionaries, mystics, artists, autodidacts—trace another genealogy of creation. More than two hundred works—paintings, films, photographs, ritual objects—enter into dialogue with the rooms of Palazzo Morando, transforming the palace into a sensitive organism, crossed by memories and presences that seem to breathe within its walls.

The title, borrowed from the poem André Breton wrote in exile in 1940, is more than a literary reference; it is a key. In those pages, written while Europe burned, Breton affirmed that “the key of dreams opens the door of the dead.”

The poem does not narrate but receives; it does not describe the world, it listens to it. The exhibition inherits that gesture and carries it forward: here, too, vision is not revelation but reception—a practice of attention to what the history of art has so often silenced, its mediumistic, involuntary, prophetic voice.

I. Breton’s Inner Ear

Fata Morgana unfolds within a constellation that moves between Breton and his spiritual heirs—Hilma af Klint, Emma Kunz, Annie Besant, Madge Gill, Augustin Lesage, Fleury-Joseph Crépin.

Figures long relegated to the edges of modernism, yet capable of setting its most secret fibers vibrating, its visionary tension made audible again.

Breton called them mediumistic artists: not image-makers but channels, those through whom the image passes rather than those who produce it.The curators—Massimiliano Gioni, Daniel Birnbaum, and Marta Papini—begin from this point of listening, an ear pressed to the century, as though trying to catch what history itself failed to hear.

Like Breton, they ask whether art might arise not from control but from surrender.

The works they have gathered do not impose themselves; they murmur. They do not seek to show the invisible; they register its tremors, its breath against the surface of the visible.The exhibition becomes an act of attunement—less a display than a séance of forms—where the living and the lost share the same vibration of light.

The large canvases by Hilma af Klint, shown for the first time in Italy, occupy the heart of the exhibition like a silent choir. Primordial Chaos—the series painted between 1906 and 1907—does not inaugurate abstraction as a language but as a revelation: circles and spirals, cosmic symmetries unfolding as if drawn from an inner order. Af Klint did not paint for herself but through herself; she received the images rather than invented them, letting them rise in her hand as one might let breath pass through a flute.

Her colours ascend and fall like currents of light, translating messages from elsewhere, tracing the movement of energies too fine to be seen.

Every form seems to emerge from the breathing of an unseen world, as if the canvas were only the skin through which that breath becomes visible. In the quiet of her studio, Hilma listens—not to the echo of the world, but to the voice that precedes it, the vibration that anticipates all form. Her spirals do not reach upward in search of heaven; they remember it. Each line returns to an origin that cannot be measured by time but only by the pulse of a vision, an expansion and contraction of the spirit. In these paintings, faith exists without religion—a stillness that prays through geometry, a devotion spoken in the rhythm of colour and breath.

The exhibition amplifies this mediumistic condition, arranging the works not by school or chronology but through secret affinities—diagrams conversing with films, photographs answering to automatic drawings, relics mirrored in performances.

It feels as if the entire display were guided by a law of sympathy rather than of history, where things are drawn together by hidden kinships, their energies converging in silence.

The result is a montage of empathy instead of chronology, a choreography of echoes in which suggestion often outweighs evidence, yet it is within this suspension that the exhibition finds its poetic breath.

Breton himself had recognised, in the work of autodidacts and spiritualist painters—from Lesage to Crépin—a purer form of Surrealism.

Fata Morgana inherits that lesson and extends it into the present: art as a phenomenon of reception rather than of expression, a state of permeability where seeing becomes a form of listening. As visitors move through the rooms, they too are transformed into mediums; the images do not demand to be seen but to be heard.

In this horizon, creativity no longer coincides with invention but with openness.

Duchamp, writing in 1957, spoke of the artist as “a mediumistic being who, from the labyrinth beyond time and space, seeks the way out toward a clearing.”

That idea breathes through the exhibition: creation as passage, a current that crosses bodies and exceeds them, a field of resonances where works gather like constellations—in Flowers of Flesh, the body becomes both prayer and burning matter; in Voices of the Spirit, speech turns to chant and apparition; in Bodies without Organs, form dissolves into energy and desire.

Each section marks a different state of being, a deeper octave of listening.

II. The House and the Countess

If Breton’s thought provides the method, the body of the exhibition is the house that contains it. Palazzo Morando, in the heart of Milan’s Quadrilatero, is not a mere container but a sensitive instrument—an organism capable of remembering.

Each room, each mirror, each brocade seems to participate in the resonance of the works.

Once the residence of Countess Lydia Caprara Morando Attendolo Bolognini—a noblewoman, theosophist, and collector of forbidden books—the palace preserves one of the most singular libraries of its time: volumes on alchemy, hermeticism, spiritism, theosophy, and manuscripts devoted to mystery and reincarnation.

It is from this secret archive that Fata Morgana arises. The exhibition does not simply converse with the space; it reactivates its memory, bringing to the surface a history of women who reconciled privilege with spiritual research, worldliness with the desire for knowledge.

Countess Bolognini, born in Alexandria in 1870 and deceased in 1954, forms the hidden heart of the exhibition—a figure poised between privilege and transcendence, between the social world of salons and the solitude of metaphysical curiosity. In her Milanese drawing room, scientists, artists, and initiates once gathered; her letters still carry the tremor of invocations, the traces of séances, reflections on the body’s departure from itself. For her, knowledge was never an edifice but a passage, a way of listening across the borders of the visible.

Born between sand and sea, she bore in her eyes both the still light of the desert and the electric pulse of Milan’s lamps. Her voice, low and measured, seemed to move within the air rather than break it; each word guarded something unspoken, as though language itself might reveal too much.

She searched not for answers but for presences, convinced that everything possessed its own double—the house, the word, even silence.

She did not study mysteries; she inhabited them, crossing knowledge as one crosses a darkened room, guided only by the pulse of intuition, the vibration of matter.

Amid the velvets and portraits her image remains, suspended like an unresolved chord, a lamp that never goes out but continues to burn quietly somewhere beyond the frame.

Echoing her presence are the photographs of Linda Gazzera and Eusapia Palladino, the plaster hands from the Lombroso Museum, the drawings of Fernand Desmoulin and Anna Hackel, the visionary works of Aloïse and Madge Gill—all born of a direct relation with the invisible, from a state of trance or automatism.

In each, gesture becomes an event that takes place beyond intention.

Amid this chorus of evidence and apparitions, the counter-liturgy of Chiara Fumai inserts itself as a partisan act of memory. The Book of Evil Spirits (2015) is not an archival video but an inverted séance—a feminist ventriloquy in which Fumai summons the silenced voices of history, returning to them both body and lexicon.

For her, the “invisible” is not what cannot be seen but what has been condemned to silence: an archive of erasures waiting to be heard again. Placed beside the albums of séances and the plaster casts preserved in collections, her work acts as their living negative, a luminous reversal that restores presence to what was taken away.

With Chiara Fumai, mediumship ceases to be transmission and becomes insubordination, an act of speech reclaimed against the powers that once suppressed it.

The same current animates the Countess’s house—a library of forbidden knowledge now reawakened as a theatre of listening. Here the exhibition reaches one of its critical thresholds: the temptation to romanticise “mediumship” gives way to a political poetics of silence, where what is muted returns not as absence but as depth.

As visitors move through the rooms, the house itself seems to accompany them.

The spaces do not separate epochs but let them overlap: baroque ceilings host the films of Maya Deren and Kenneth Anger; eighteenth-century furnishings frame the neon works of Kerstin Brätsch; the vitrines hold, side by side, ancient books and shards of contemporary glass.

Everything breathes within a single temporality—the time of vision. It is as if the exhibition had awakened the palace, restoring to it its nature as a mediumistic body.

Walls saturated with memory and with voices become surfaces of projection; the Countess, who once practised automatic writing as a path of knowledge, seems still to dictate from afar, her words suspended between centuries. Architecture here turns into metaphor: the work of art as a body inhabited by multiple presences, each room a mental chamber where past and present exchange their pulse.

The contemporary works—from Giulia Andreani to Marianna Simnett—do not interrupt this dialogue but carry it forward: in Conservative Ghost (Aetas Ferrea),2024, Andreani paints a female spectre who is not apparition but political memory, while in Leda Was a Swan (2025), Simnett transforms myth into digital trance. In both, the state of possession migrates into technological language; vision becomes algorithm, ecstasy translates as code.

From the first telegraphic signals to today’s data streams, the invisible only changes its instrument, never its nature—it still searches for bodies through which to pass, for channels in which to become sound, light, vibration.

Thus Palazzo Morando reveals itself as a living archive, a palimpsest joining the aristocratic substance of the past to the hybrid matter of the present, as if the house, in its suspended elegance, were hosting an experiment in cultural reincarnation—the soul of Europe’s spiritual modernism finding, in the contemporary, its echo.

III. The Legacy of the Unseen

The second half of the exhibition moves through the twentieth century and into the present, following the fine thread that binds mysticism to technology, ritual to the moving image.

In Maya Deren’s The Witch’s Cradle (1943) and Kenneth Anger’s Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome (1954–78), cinema becomes an instrument of trance: bodies drift through weightless space, gestures repeat like incantations, and light itself ceases to illuminate—it conjures, turning vision into a form of mediumship.

Through photography, Man Ray and Lee Miller extend the Surrealist experiment: Groupe Surréaliste (Séance d’écriture automatique, 1924–1980) and Robert Desnos (1925) are images born of chance, of time folding into desire. As in Breton’s writings, vision here is an act of reception, a way of letting what cannot yet be understood pass through.

Unica Zürn transforms automatic writing into a trance of the body; her words curl like inked serpents, diagrams of a possession that is both suffering and revelation.

For her, automatism is not an exercise but a surrender, an opening on the threshold between language and madness. The reflection returns to the plane of the body with the images of Carol Rama and the ceramics of Chiara Camoni.

In Rama’s watercolours, sexuality becomes ritual, confession, provocation; in Camoni’s hands, sculpture turns vegetal, a breathing organism that seems to grow toward the light.

Kerstin Brätsch, with her polychrome glass panels, reclaims the language of alchemy, translating it into mirror-paintings whose surfaces flare and fade like apparitions, suspended between matter and spirit.

Echoing what has already emerged, the voice of Chiara Fumai acts here as a hinge between historical genealogies and the present. In The Book of Evil Spirits she fuses séance, performance, and pamphlet, transforming the mediumistic act into a practice of counter-narration.

If the Surrealist trance exposed the unconscious as a territory without master, Fumai reveals its debt: every voice that speaks “through” is also a voice spoken “by” the structures of power. Her work becomes a pedagogy of invocation—learning to call by name and to make speak the presences expelled from the canon, until the script of history itself can be rewritten.

Mediumship becomes not transmission but agency: the right to speak, the right to return.

Within this weave of voices and apparitions, art appears not only as listening but as healing—a thaumaturgic gesture that seeks to mend the fracture of the world, as if, in becoming vision, it still tried to heal the wound of the real, the one that binds pain to hope, matter to its invisible double.

Feminine voices flow through the exhibition like an underground river. From the nineteenth-century theosophists to Judy Chicago and Andra Ursuţa, this genealogy of the feminine unfolds as a long transmission of mediumship— not a linear history but a current of resistance, women who once spoke through spirits to challenge the hierarchies of knowledge and now speak through technology to confront those of power.

Through them, the notion of the invisible shifts from metaphysical dimension to political terrain, from afterlife to interstice. Contemporary women artists no longer search for the afterlife but for the beyond-vision: the image as threshold, a site where the body can dematerialise and reaffirm itself at once.

La Gola (2024) by Diego Marcon closes the exhibition as a contemporary requiem.

This CGI animation, poised between cartoon and elegy, breathes like a living being and thinks like an algorithm; the afterlife appears here not as promise but as loop.

Marcon tells of a hunger that cannot be appeased: a voice that tastes and one that suffers, walking side by side without meeting. In his words one feels the breath of the body—its slow surrender, its longing to remain.

The faces are still, the eyes barely move; it is there that the image begins to breathe, like a prayer murmured under one’s breath. Within Fata Morgana, the film becomes its mirror: reality as mirage, reflection that deceives only to reveal the truth.

Marcon’s gaze lingers where light yields to darkness—in the throat that swallows and the silence that returns, at the point where the invisible begins to take flesh.

Across the exhibition, like a breath crossing centuries, the visions of Corita Kent, Minnie Evans, Gertrude Morgan, Marian Spore Bush, and Vanda Vieira-Schmidt resurface—women who painted as one prays, as one calls for salvation. Their images, born of fervour and necessity, are hymns of light and despair, prophecies entrusted to colour.

With them, art and faith are no longer separate but share the same body, the same last visible form. Before dissolving, the invisible translates itself into gesture, into prayer, into a dream of redemption.

Along the way, an undercurrent of irony threads through the works of Man Ray, Max Ernst, and Pierre Klossowski—the awareness that the sacred, to exist, must pass through the mask.

Beside them, the carnal visions of Jill Mulleady recast martyrdom as a modern trance: bodies suspended between ecstasy and wound, where painting becomes relic and apparition at once.

Marcel Duchamp had already sensed it when he wrote that the artist is an unconscious medium, and Carol Rama, decades later, confirmed it, overturning the very notion of inspiration into a practice of flesh and desire.

IV. Epilogue: The Threshold and the Return

Perhaps every project of Fondazione Nicola Trussardi contains not so much an act of transmigration as one of dispossession: a willingness to let art lose its boundaries and become a collective passage.

Fata Morgana does not merely leave canonical spaces; it transforms them from within, as if Milan itself—the city, its memory, its palaces—were the medium of an older voice.

In this metamorphosis, the city appears as both a mediumistic and a technological body, a network of electric wires and subterranean currents where memory coexists with circuitry and enchantment endures at the heart of modernity.

Palazzo Morando does not host; it resonates. It is a chamber of echoes in which centuries overlap, a dwelling that, for an instant, seems to remember having once been a body.

In the Countess’s library, the volumes of Fludd, Lavater, Dionysius the Areopagite, and Masen do not appear as relics but as presences awaiting rereading.

Their pages, marked by time and devotion, offer no answers—they hold questions.

It is within that silence that the exhibition closes, and in closing, opens again, as though every forbidden knowledge required an ear in order to go on existing.

We live immersed in new digital superstitions, surrounded by disembodied presences and by images that no longer ask to be believed.

Fata Morgana returns a different temperature to that ocean of simulacra: it reminds us that the image is not a code but a voice, and that to see still means to listen.

Its power lies not in revealing the invisible but in allowing it to filter through form, like an underground current that continues to flow despite everything.

The works unfold as sentences in an endless discourse—not a narrative but a shared breath. Each figure—from Hilma af Klint to Marianna Simnett, from Annie Besant to Diego Marcon—is an accent in this posthumous language that speaks of us more than we can understand ourselves.

In this sense, mediumship is not a marginal phenomenon but a posture of thought: the readiness to be traversed, to let something pass through us.

Fata Morgana thus becomes the portrait of a desire—not belief in magic, but in the possibility that the image still holds a portion of truth that does not belong to us.

It is a journey through the double mirrors of vision—between faith and knowledge, memory and prophecy—seeking not reconciliation but continuity.

As André Breton wrote in Mad Love (1937) — “the real is what will not allow itself to be closed off” — reality remains a threshold, an open passage.

It is perhaps within this opening that the exhibition finds its voice: in the fragile, shifting space that separates perception from revelation, where knowledge becomes echo and mystery, for an instant, becomes inhabitable.

Like an echo in the Countess’s library — or in the concentric silence of Hilma af Klint’s studio — the exhibition folds back upon itself, allowing vision to go on breathing through time.