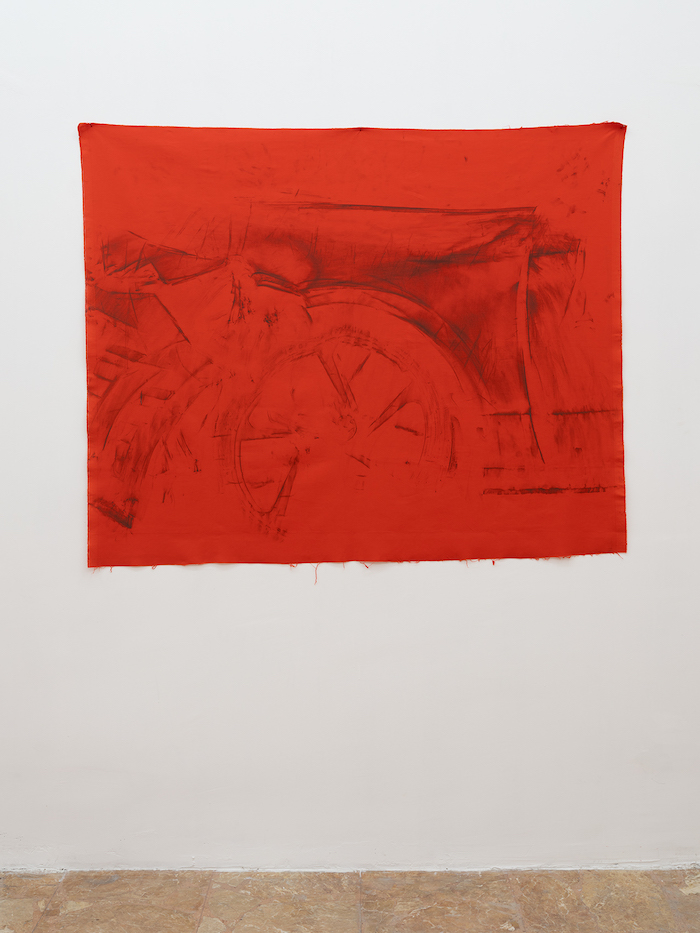

Il rosso non è mai innocente. È allarme, ferita, eccedenza. È la materia che lampeggia come segnale di pericolo e, al tempo stesso, attira come promessa di collisione. Nella personale di G.Küng alla Galleria Le Vite, Car Rubbings on Red, il rosso si offre come superficie di registrazione: non colore, ma campo di iscrizione, tessuto impregnato di grafite che trattiene il contatto traumatico con l’automobile, emblema della modernità. Qui il gesto dell’artista non inventa immagini, ma lascia che esse emergano come impronte, come tracce fantasmatiche di un urto già avvenuto e destinato a ripetersi. Il rosso, quando appare, non lascia tregua. È il colore del semaforo che ci ferma a un incrocio, del sangue che ci scorre dentro e non si vede, del tramonto che chiude i conti con il giorno. È un colore che non si accontenta di farsi sfondo: avanza, occupa, pretende lo sguardo. Nel rosso c’è un’urgenza che assomiglia alla vita e al suo contrario, come una lama che vibra tra slancio e ferita. “Il rosso è la radice della vita, la sua vibrazione più alta”1. In Küng questa radice si tramuta in cicatrice: ciò che vibra non è più soltanto energia, ma il resto di un impatto.

Cassandra Seltman, nel testo che accompagna la mostra, richiama l’automaton dell’Iliade: i cancelli del cielo che si aprono da soli, senza agente esterno. La parola dice di un movimento che procede da sé, inesorabile, come la psiche che torna sempre al medesimo solco. Freud ha distinto questa forza cieca – la coazione a ripetere – dalla tuchē, l’incontro casuale, l’urto imprevisto che incrina l’ordine. Le opere di Küng nascono in questo spazio di collisione: l’automaton della ripetizione incontra la frattura del caso, e ciò che rimane è un segno. La grafite strofinata sul tessuto rosso diventa allora il sismografo di un evento che non si lascia ricomporre, il diagramma di un trauma che si scrive per stratificazione. Rosso è anche il colore della memoria, che torna a ondate. È il colore delle bandiere spiegate al vento e dei teli stesi ad asciugare nei vicoli, il colore delle feste e dei lutti. È un colore collettivo, che appartiene ai corpi in marcia e alle folle che gridano. Ma in solitudine diventa intimo, un rosso chiuso che pulsa dentro la pelle, un richiamo che non ha bisogno di voce. Georges Bataille, nelle sue Lacrime di Eros, lega il rosso al sangue che bagna i sacrifici2. Küng sembra riformulare questa associazione: il rosso non come simbolo, ma come pelle viva che trattiene urti e ferite.

Il frottage, adottato dai surrealisti come automatismo psichico, torna qui con altro peso. In Max Ernst la tecnica liberava forme latenti, permetteva alla materia di rivelare i propri fantasmi. In Küng, invece, il frottage non produce immagini inconsce, ma registra urti concreti: lamiere piegate, parabrezza fratturati, fari incrinati. La mano dell’artista non disegna, ma accompagna lo strofinamento, lasciando che la superficie colpita dal reale si trasferisca in traccia. Ciò che appare non è documento tecnico, bensì fantasma. Come direbbe Roland Barthes, il frottage non mostra ciò che “è stato”, ma ciò che continua a ritornare: non un “ça a été”, ma un “ça insiste”3. L’incidente, nel lavoro di Küng, è figura di pensiero prima che immagine. Paul Virilio, in L’incidente del futuro, scriveva che ogni nuova tecnologia inventa anche il proprio disastro4. Le tele rosse di Küng, tutte del 2025, testimoniano questa logica implacabile. Se l’automobile ha incarnato nel Novecento il mito della libertà, essa porta inscritto in sé il proprio rovescio: l’arresto, la collisione, la morte. La grafite che disegna le superfici contorte non è allora soltanto memoria di un danno, ma mappa di una condizione storica: la modernità come accelerazione che porta in sé la propria catastrofe.

Se Virilio ci ha insegnato a vedere nell’invenzione di ogni tecnica il germe del suo disastro, Timothy Morton ci costringe a guardare più lontano: agli “iper-oggetti” come il riscaldamento globale o il collasso ecologico5. Mark Fisher parlerebbe di un presente sequestrato, di una catastrofe senza evento, che ci avvolge come aria e ci impedisce di immaginare il dopo6. In questo senso, il crash automobilistico evocato da G.Küng diventa emblema di un destino più vasto: la modernità intera che procede verso il suo incidente diffuso.

Non è un caso che il rosso domini la mostra. È il rosso dei segnali stradali, ma anche quello della corrida evocata nel testo curatoriale: un colore che dovrebbe ammonire, ma che spinge invece a caricare, ad avanzare verso l’impatto. È il rosso come bandiera politica, memoria di rivolte e di energie collettive, ed è anche, più silenziosamente, il rosso della carne, della ferita, del corpo esposto. Nelle tele di Küng il rosso è insieme superficie e abisso: campo su cui si scrive l’impronta e voragine che inghiotte lo sguardo. Franco “Bifo” Berardi ha descritto questa tonalità come l’incandescenza emotiva di un’epoca che brucia le proprie energie: il rosso della velocità che diventa panico, dell’euforia che precipita in depressione collettiva7. È lo stesso colore che nelle tele di Küng non celebra, ma consuma: una bandiera che non raduna ma disperde, un calore che non unisce ma sfibra. “Il rosso ha in sé qualcosa di inquieto, un’irrequietezza che non conosce riposo”, annotava Goethe nella sua Teoria dei colori8. Julia Kristeva, parlando dell’abietto, riconduce il rosso al corpo che si espone, al sangue che non può essere ricondotto a forma9. Le tele di Küng sembrano incarnare proprio questa dimensione: il rosso come forza che sfugge al controllo, che interrompe il linguaggio e lo riconduce alla materia nuda. Il rosso qui diventa la lingua stessa dell’opera. Una lingua che non si legge ma si sente, come il battito che accelera all’improvviso, come il calore che sale al volto. È il colore che non ammette indifferenza, che divide e spacca: o ti trattiene, o ti spinge. È il colore della sopravvivenza, dei fuochi accesi nei bivacchi, dei fari che lampeggiano nella notte. Il rosso di Küng non è mai puro: è intriso di grafite, ferito, opaco. È un rosso vissuto, che porta dentro di sé la memoria dei colpi.

Il reticolo fratturato di un fanale in Cracked Headlight si trasforma in disegno nervoso, quasi un grafo neuronale spezzato. Il faro, organo destinato a illuminare la strada e aprire un cammino, si incrina e si spegne: ciò che dovrebbe rischiarare diventa opacità, la trama luminosa si fa ombra, nervatura spezzata, segnale che la visione è sempre a rischio di frattura. Con Two Cars Rubbing on Red la collisione si dilata fino a farsi indistinta: non più dettaglio ma onda d’urto, corpo a corpo in cui le parti non sono separabili. Il formato allungato, quasi panoramico, amplifica l’effetto di scontro: due presenze che si urtano fino a fondersi in un unico campo visivo, come se la tela fosse un’arena, un fronte di battaglia. La serialità dei segni ribadisce l’impossibilità di distinguere tra un prima e un dopo: resta solo il momento sospeso dell’impatto. Car That’s Been in a Crash porta già nel titolo la dichiarazione del trauma: non un’auto qualsiasi, ma un corpo ferito. Il frottage non raffigura, ma raccoglie la pelle contusa del metallo, come negativo di un urto. In Window Down emerge invece l’idea di apertura: non soltanto lamiera, ma il finestrino abbassato, luogo del passaggio, del contatto tra interno ed esterno, che qui si trasforma in impronta opaca. Diversa è la percezione davanti a Truck Rubbing on Red, dove la massa è imponente, collettiva: non più un corpo privato, ma un gigante industriale. Il camion, veicolo di lavoro e di merci, diventa segno monumentale, crash che porta con sé la storia di una forza più grande, sovrapersonale.

Queste immagini non narrano, non illustrano: sono iscrizioni. Come incisioni rupestri del contemporaneo, conservano il trauma come traccia astratta, senza mai restituirlo nella sua immediatezza. È qui che risuona la lezione di Walter Benjamin: “La vera immagine del passato passa di sfuggita”10. Le tele di Küng trattengono quell’immagine fugace, residuo di un urto che non si lascia rappresentare, ma solo imprigionare in un segno.

La memoria, come ricorda Freud nel Wunderblock, è una superficie che trattiene solchi invisibili11. Ogni nuova iscrizione cancella e conserva al tempo stesso. Le opere di Küng sono Wunderblöcke contemporanei: tessuti rossi che portano solchi neri, tracce di una scrittura non alfabetica ma traumatica. Eppure la nostra epoca ha mutato questo dispositivo. Il Wunderblock è diventato tablet, superficie liscia e infinita che registra e genera senza limiti. L’intelligenza artificiale, nuovo automaton, produce memorie e allucinazioni, mescola ricordo e invenzione. All’opposto, i frottage di Küng insistono sul limite, sull’impronta irripetibile, sul segno che non si lascia cancellare. Sono un atto di resistenza alla smaterializzazione digitale: il ritorno ostinato della materia, della polvere di grafite che sporca e annerisce. Freud descriveva il “taccuino magico” come un giocattolo semplice: una tavoletta di cera coperta da un foglio trasparente che permetteva di scrivere e cancellare a piacimento. Ciò che appariva scompariva, ma le tracce restavano impresse sotto la superficie, invisibili. Era per lui la perfetta metafora del funzionamento psichico: percezione che svanisce e ricordo che persiste. In Küng il dispositivo si rovescia. Non c’è cancellazione, non c’è oblio: ogni frottage è ferita che rimane, grafite che insiste. Il suo lavoro non celebra la duttilità della memoria, ma la sua ostinazione, la sua incapacità di cancellare del tutto l’urto. Le tele rosse diventano allora anti-Wunderblock, superfici dove il trauma resta inciso, dove il tempo non scorre ma si stratifica in cicatrici.

La presenza del Conceptual Model With Apertures in plexiglass accentua questa dialettica. La trasparenza geometrica contrasta con l’opacità sporca delle tele. Da un lato la memoria astratta, razionale, che si offre come schema; dall’altro la memoria traumatica, segnata dal contatto fisico. È la tensione tra archivio digitale e ferita corporea, tra astrazione algoritmica e residuo materiale. In mezzo, lo spettatore, chiamato a interrogare la propria posizione di fronte alla ripetizione cieca e all’incontro imprevisto.

Milano, città di accelerazione produttiva e di improvvise fratture, non è soltanto scenario ma parte del discorso. Portare in galleria i segni della collisione automobilistica significa mostrare il lato oscuro di una città che si misura spesso solo sulla sua capacità di correre. Il lavoro di Küng espone il trauma come condizione comune, l’incidente come logica del presente. E nel farlo restituisce al rosso il suo statuto enigmatico: avvertimento e attrazione, stop e accelerazione, ferita e energia. In queste tele, ciò che conta non è tanto l’oggetto raffigurato, quanto il processo che vi si deposita. Non pittura, non disegno, non fotografia: traccia. Scrittura che non appartiene a nessun medium, ma che li attraversa tutti. È in questo attraversamento che si manifesta la forza lirica di questo lavoro: le opere sono al tempo stesso residui e apparizioni, documenti e spettri, impronte e visioni. Non chiudono, ma aprono. Non spiegano, ma inquietano.

Se l’automaton è il movimento che si ripete da sé, allora l’incidente è ciò che interrompe e rigenera. Car Rubbings on Red ci mostra che ogni frattura può diventare iscrizione, ogni trauma linguaggio, ogni urto memoria. Non per guarire, ma per ricordare che nella ripetizione cieca si annida sempre un punto di rottura, e che è da lì che nasce la possibilità di un’altra immagine. Viviamo in un tempo in cui il disastro non è più eccezione ma condizione: lo vediamo nei blackout tecnologici, nei mari che invadono le città, nelle centrali che collassano, nelle guerre che trasformano le metropoli in scheletri fumanti. Jean-Luc Nancy ricordava che il disastro è un intruso che entra nei corpi e li altera12. Le tele di Küng si iscrivono in questa cronaca contemporanea: non raffigurano incidenti automobilistici, ma ci ricordano che ogni collisione porta con sé l’eco di quelle più grandi, collettive, planetarie.

- Wassily Kandinsky, Lo spirituale nell’arte (1911), trad. it. A. Colasanti, Milano, SE, 1989, p. 86. ↩︎

- Georges Bataille, Lacrime di Eros (1961), trad. it. G. Piana, Milano, SE, 1991, p. 44. ↩︎

- Roland Barthes, La camera chiara. Nota sulla fotografia (1980), trad. it. R. Guidieri, Torino, Einaudi, 1980, p. 88. ↩︎

- Paul Virilio, L’incidente del futuro (2002), trad. it. P. Jedlowski, Genova, Il Nuovo Melangolo, 2005, p. 29. ↩︎

- Timothy Morton, Iperoggetti. Filosofia ed ecologia dopo la fine del mondo (2013), trad. it. E. Sforza, Roma, NERO Editions, 2018, p. 27. ↩︎

- Mark Fisher, Realismo capitalista. È più facile immaginare la fine del mondo che la fine del capitalismo? (2009), trad. it. V. Dini, Roma, NERO Editions, 2018, p. 15. ↩︎

- Franco “Bifo” Berardi, La crisi della presenza, Roma, DeriveApprodi, 2018, p. 62. ↩︎

- Johann Wolfgang Goethe, La teoria dei colori (1810), trad. it. G. Faggin, Milano, Il Saggiatore, 1970, p. 219. ↩︎

- Julia Kristeva, Poteri dell’orrore. Saggio sull’abiezione (1980), trad. it. L. L. Goglia, Milano, Spirali, 1988, p. 12. ↩︎

- Walter Benjamin, Tesi di filosofia della storia (1940), in Angelus Novus. Saggi e frammenti, trad. it. R. Solmi, Torino, Einaudi, 1962, p. 80. ↩︎

- Sigmund Freud, Nota sul “taccuino magico” (1925), in Opere, vol. 10, trad. it. C. Musatti, Torino, Boringhieri, 1976, p. 253. ↩︎

- Jean-Luc Nancy, L’Intruso (2000), trad. it. G. Zanini, Genova, Il Nuovo Melangolo, 2000, p. 17. ↩︎

G. Küng, Car Rubbings on Red | Le Vite, Milan

Red is never innocent. It is alarm, wound, excess. It flares like a warning signal and, at the same time, entices as a promise of collision. In G. Küng’s solo exhibition at Le Vite, Car Rubbings on Red, red emerges not as mere colour but as a surface of recording: not hue, but field of inscription, fabric saturated with graphite that preserves the traumatic contact with the automobile, emblem of modernity. Here the artist’s gesture does not invent images but lets them surface as imprints, as spectral traces of an impact already occurred and bound to repeat itself. When red appears, it grants no respite. It is the colour of the traffic light that halts us at an intersection, of the blood that courses within us unseen, of the sunset that settles the day’s accounts. It is a colour that refuses to remain backdrop: it advances, occupies, demands the gaze. In red there is an urgency that resembles both life and its opposite, like a blade vibrating between impulse and wound. “Red is the root of life, its highest vibration”¹. In Küng this root becomes scar: what vibrates is no longer pure energy, but the remainder of an impact.

Cassandra Seltman, in the text accompanying the exhibition, recalls the automaton of the Iliad: the gates of heaven that open by themselves, without external agent. The word designates a movement that advances of its own accord, inexorable, like the psyche returning always to the same furrow. Freud distinguished this blind force—the compulsion to repeat—from tuchē, the chance encounter, the unforeseen impact that disrupts order. Küng’s works are born in this space of collision: the automaton of repetition meeting the fracture of chance, leaving behind only a sign. Graphite rubbed onto red fabric becomes the seismograph of an event that resists repair, the diagram of a trauma inscribed through stratification.

Red is also the colour of memory, surging in waves. It is the colour of flags unfurled in the wind and of cloths hung out to dry in alleyways, the colour of festivals and of mourning. A collective colour, belonging to marching bodies and shouting crowds. Yet in solitude it turns intimate, a closed red pulsing beneath the skin, a summons that requires no voice. Georges Bataille, in The Tears of Eros, links red to the blood that drenches sacrifice². Küng seems to reformulate this association: red not as symbol, but as living skin that holds the shocks and wounds within itself.

Frottage, adopted by the Surrealists as a psychic automatism, returns here with a different weight. In Max Ernst the technique liberated latent forms, allowing matter to disclose its own phantoms. In Küng, by contrast, frottage does not conjure unconscious images but records concrete impacts: bent sheets of metal, fractured windshields, cracked headlights. The artist’s hand does not draw; it accompanies the rubbing, letting the surface struck by reality transfer itself into trace. What appears is not a technical document but a ghost. As Roland Barthes would have it, frottage does not show what “has been,” but what continues to return: not a ça a été but a ça insiste³.

In Küng’s work, the accident is a figure of thought before it is an image. Paul Virilio, in The Original Accident, wrote that every new technology invents its own disaster⁴. Küng’s red canvases, all from 2025, testify to this implacable logic. If the automobile embodied in the twentieth century the myth of freedom, it also inscribed within itself its own reversal: arrest, collision, death. The graphite delineating the contorted surfaces is not only the memory of a damage but also the map of a historical condition: modernity as acceleration carrying within itself its own catastrophe.

If Virilio taught us to see in the invention of every technique the seed of its disaster, Timothy Morton compels us to look further: to “hyperobjects” such as global warming or ecological collapse⁵. Mark Fisher would speak of a present under sequestration, of a catastrophe without event, enveloping us like air and preventing us from imagining what comes after⁶. In this sense, the automobile crash evoked by Küng becomes the emblem of a broader destiny: modernity itself advancing toward its diffuse accident.

It is no accident that red dominates the exhibition. It is the red of road signs, but also that of the bullfight evoked in the curatorial text: a colour that ought to warn, yet instead incites the charge, the advance toward impact. It is the red of the political banner, memory of uprisings and collective energies, and, more silently, the red of flesh, of the wound, of the exposed body. In Küng’s canvases, red is at once surface and abyss: a field on which the imprint is written and a chasm that swallows the gaze. Franco “Bifo” Berardi has described this tonal register as the emotional incandescence of an era that burns through its own energies: red as the velocity that turns to panic, euphoria tipping into collective depression⁷. It is the same colour that, in Küng’s work, does not celebrate but consumes: a flag that no longer gathers but disperses, a heat that does not unify but frays.

“Red has in itself something restless, an unease that knows no repose,” noted Goethe in his Theory of Colours⁸. Julia Kristeva, in speaking of the abject, traces red back to the body exposed, to blood that cannot be restored to form⁹. Küng’s canvases seem to embody precisely this dimension: red as a force that escapes control, that interrupts language and returns it to naked matter.

Here red becomes the very language of the work. A language not to be read but to be felt, like a heartbeat suddenly quickening, like heat rising to the face. It is the colour that admits no indifference, that cleaves and divides: either it holds you, or it pushes you away. It is the colour of survival, of fires lit in encampments, of headlights flashing in the night. Küng’s red is never pure: it is scarred with graphite, wounded, opaque. It is a lived red, carrying within itself the memory of blows.

The fractured lattice of a headlamp in Cracked Headlight turns into a nervous drawing, almost a broken neural graph. The headlight, an organ meant to illuminate the road and open a path, cracks and goes dark: what should guide instead collapses into opacity, the luminous weave becoming shadow, a severed nerve, a sign that vision itself is always at risk of fracture. With Two Cars Rubbing on Red, the collision expands until it becomes indistinct: no longer detail but shockwave, a body-to-body encounter in which the parts are inseparable. The elongated, almost panoramic format amplifies the clash: two presences colliding until they merge into a single field of vision, as though the canvas were an arena, a battlefield. The seriality of the marks underscores the impossibility of distinguishing a before from an after: what remains is only the suspended moment of impact.

Car That’s Been in a Crash already declares the trauma in its title: not any car, but a wounded body. Frottage here does not depict but gathers the bruised skin of metal, the negative of an impact. In Window Down what emerges instead is the notion of openness: not merely sheet metal, but the lowered window, site of passage, of contact between interior and exterior, which here is transformed into an opaque imprint. Quite different is the perception before Truck Rubbing on Red, where the mass is imposing, collective: no longer a private body but an industrial giant. The truck, vehicle of labour and goods, becomes a monumental sign, a crash that carries within itself the history of a force greater than the individual, supra-personal.

These images do not narrate; they do not illustrate: they are inscriptions. Like contemporary petroglyphs, they preserve trauma as abstract trace, never restoring it in its immediacy. Here resonates Walter Benjamin’s lesson: “The true image of the past flits by”¹⁰. Küng’s canvases hold onto that fleeting image, residue of an impact that cannot be represented but only imprisoned in a mark.

Memory, as Freud reminds us in the Mystic Writing-Pad, is a surface that retains invisible furrows¹¹. Every new inscription both erases and preserves. Küng’s works are contemporary Wunderblöcke: red fabrics bearing black grooves, traces of a writing not alphabetic but traumatic. And yet our age has transformed this device. The Wunderblock has become the tablet, a smooth and infinite surface that registers and generates without limit. Artificial intelligence, the new automaton, produces memories and hallucinations, mingles recollection and invention. In contrast, Küng’s frottages insist upon limit, upon the irreducible imprint, upon the mark that refuses to be erased. They are an act of resistance to digital dematerialization: the obstinate return of matter, of graphite dust that soils and blackens.

Freud described the “magic writing-pad” as a simple toy: a wax tablet covered by a transparent sheet on which one could write and erase at will. What appeared would disappear, yet the traces remained impressed beneath the surface, invisible. For him it was the perfect metaphor of psychic function: perception fading, memory persisting. In Küng the device is reversed. There is no erasure, no oblivion: every frottage is a wound that remains, graphite that insists. Her work does not celebrate the ductility of memory, but its obstinacy, its inability ever fully to cancel the shock. The red canvases then become anti-Wunderblocks, surfaces where trauma remains inscribed, where time does not flow but stratifies into scars.

The presence of the Conceptual Model With Apertures in plexiglass accentuates this dialectic. Its geometric transparency contrasts with the soiled opacity of the canvases. On one side abstract, rational memory that presents itself as schema; on the other, traumatic memory, marked by physical contact. It is the tension between digital archive and bodily wound, between algorithmic abstraction and material residue. In between stands the spectator, called upon to interrogate their own position before blind repetition and unforeseen encounter.

Milan, city of productive acceleration and sudden fractures, is not mere backdrop but part of the discourse. To bring into the gallery the signs of automobile collisions means to expose the dark underside of a city so often measured only by its capacity to run. Küng’s work lays bare trauma as a shared condition, the accident as the logic of the present. And in so doing it restores to red its enigmatic status: both warning and allure, stop and acceleration, wound and energy.

What matters in these canvases is not the object depicted but the process that deposits itself upon them. Not painting, not drawing, not photography: trace. A writing that belongs to no medium, yet traverses them all with insistence. In this crossing lies the lyrical force of her work: the pieces are at once residues and apparitions, documents and spectres, imprints and visions. They do not close, but open. They do not explain, but unsettle.

If the automaton is movement repeating itself, then the accident is what interrupts and regenerates. Car Rubbings on Red shows us that every fracture may become inscription, every trauma a language, every shock a memory. Not to heal, but to remind us that within blind repetition there always nests a point of rupture, and it is from there that another image may be born.

We live in a time when disaster is no longer exception but condition: we see it in technological blackouts, in seas invading cities, in collapsing power plants, in wars that turn metropolises into smoking skeletons.

Jean-Luc Nancy reminded us that disaster is an intruder that enters bodies and alters them, an intrusion that unsettles the very sense of self and community. ¹². Küng’s canvases inscribe themselves into this contemporary chronicle: they do not depict car crashes, but they remind us that each collision carries the echo of greater ones, collective, planetary.

¹ Wassily Kandinsky, Concerning the Spiritual in Art (1911), trans. M. Sadler, New York: Dover, 1977, p. 86.

² Georges Bataille, The Tears of Eros (1961), trans. P. Connor, San Francisco: City Lights, 1989, p. 44.

³ Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography (1980), trans. R. Howard, New York: Hill and Wang, 1981, p. 88.

⁴ Paul Virilio, The Original Accident (2002), trans. J. Rose, Cambridge: Polity Press, 2007, p. 29.

⁵ Timothy Morton, Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World (2013), Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013, p. 27.

⁶ Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? (2009), London: Zero Books, 2009, p. 15.

⁷ Franco “Bifo” Berardi, La crisi della presenza (Rome: DeriveApprodi, 2018), p. 62 [my translation].

⁸ Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Theory of Colours (1810), trans. C. L. Eastlake, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1970, p. 219.

⁹ Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection (1980), trans. L. S. Roudiez, New York: Columbia University Press, 1982, p. 12.

¹⁰ Walter Benjamin, Theses on the Philosophy of History (1940), in Illuminations, ed. H. Arendt, trans. H. Zohn, New York: Schocken Books, 1968, p. 255.

¹² Sigmund Freud, A Note upon the “Mystic Writing-Pad” (1925), in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, vol. 19, trans. J. Strachey, London: Hogarth Press, 1961, p. 227.

¹³ Jean-Luc Nancy, “L’Intrus” (2000), trans. S. Hanson, in The New Centennial Review, vol. 2, no. 3 (2002), pp. 1–14, here p. 3.