English text below —

Parabita si trova a sud del sud, sul dorso pietroso della Puglia che scende verso il mare come un animale che riposa. È lì, tra la costa ionica che brilla in lontananza e l’entroterra carsico che inghiotte la luce, che il paese si allunga, silenzioso, come una vena d’ombra nella carne del Salento. Non è sul mare, ma ne sente il respiro. Non è nell’interno, ma si ritrae, come fa il silenzio quando viene ascoltato davvero. Parabita è più vicina alla pietra che all’aria, più prossima alla memoria che al presente. È una geografia in sottrazione, scavata, tenace. Sta sopra e sotto allo stesso tempo: poggiata sul dorso calcareo della Serra, ma con radici che affondano in camere fredde, in cunicoli, in fenditure del tempo. Se la si cerca sulle mappe, la si trova tra Gallipoli e Tuglie, tra Matino e Alezio. Ma per chi ascolta il Sud come un corpo, Parabita è quel punto in cui il respiro si ferma un istante, e il tempo si fa verticale. Dove le mani hanno lavorato la roccia come se fosse pane, e la luce ha imparato a entrare con pudore. È una lezione di durata: qui la storia non si misura a scosse, ma a stratificazioni, il buio non è mai deserto, ma grembo che prepara e nella pietra che accoglie e custodisce, la comunità riconosce sé stessa e trova ancora, nel presente, la sua eredità di futuro. Parabita per il contemporaneo è uno sguardo che tiene insieme le radici e il tempo che viene. Non misura la ricchezza nei beni, ma nei segni che restano, nei pensieri che accendono, nelle meraviglie che sanno sorprendere. È un segno che trattiene dall’abitudine, e ricorda che l’arte sa ancora creare comunità.

Nel 2024 Votiva ha avviato il cammino, lasciando che fossero le edicole sacre a indicare la strada. Là dove un tempo si lasciava un fiore, una candela, una preghiera sussurrata, ora si apre lo spazio per un altro gesto: quello l’arte che continua a custodire e a trasformare.

Da un’idea del sindaco Stefano Prete, a cura di Flaminia Bonino e Laura Perrone e con la direzione artistica di Giovanni Lamorgese, Votiva non è semplicemente una collezione d’arte pubblica. È un fiato ridato alle pietre, una brace che riaccende i vicoli, non raccoglie soltanto opere, ma frammenti di memoria, che tornano a pulsare dentro quelle edicole devozionali e affiorano come vene di pietra nella trama di Parabita.

Nell’antica Roma l’aedicula era una vera e propria casa in miniatura. Due colonne, un frontone, un’ombra al centro: bastava questo per dire che il divino poteva abitare accanto all’uomo. Non c’era distanza tra il tempio e la strada, tra l’atrio di una domus e l’angolo d’un vicolo dove nella misura di una nicchia, si raccoglieva il cosmo. Si passava accanto a una nicchia sacra come a un respiro trattenuto. I Lari, divinità tutelari che vegliavano sui crocicchi, i passaggi e le soglie, e i Penati, dei del focolare e delle provviste, tenevano compagnia al viandante e proteggevano la casa. Non più l’immenso, ma il piccolo, il cosmo piegato nella fenditura di un muro: all’incrocio di una strada, sulla soglia tra la notte e il ritorno. Un lume acceso bastava. Un fiore bastava. Il dio restava vicino, domestico, fragile come l’attesa che non si compie mai del tutto. Mircea Eliade li avrebbe chiamati “centri del sacro”, piccoli varchi attraverso cui l’eterno irrompe nello spazio profano, apparizioni del senso. Non un significato compiuto, ma il suo farsi e disfarsi tra un’immagine dipinta e il muro che la ospita. Nella loro minuta resistenza, questi altari da strada sembrano incarnare ciò che Georges Didi-Huberman ha riconosciuto nelle immagini: la capacità di ardere nel tempo, di brillare come lucciole ostinate nel buio. Custodiscono figure che non sono reliquie morte, ma scintille che legano il passato al presente. Sono dispositivi che catturano e trattengono una presenza altrimenti fuggitiva, piccole macchine teologiche in cui la comunità riconosce ancora oggi la propria fragilità e la propria attesa. Dal punto di vista dello spazio urbano, l’aedicula è un’eterotopia, un luogo altro, incastonato nella continuità dell’urbano e insieme sospeso da esso. Una fenditura che interrompe il ritmo della strada, e ricorda a chi passa che c’è sempre un oltre, un altrove possibile. Le edicole votive di Parabita, sono tessere vive: il loro Genius Loci è ancora la capacità di radicare la comunità nello spazio e nel tempo, a ciò che resiste all’anonimato. Francesco Arena, Chiara Camoni, Ludovica Carbotta, Claire Fontaine, Gianni Dessi, ektor garcia, Helena Hladilova, Felice Levini, Claudia Losi, K.R.M. Mooney, Liliana Moro, Adrian Paci, Mimmo Paladino, Michelangelo Pistoletto, Luigi Presicce, Namsal Siedlecki : sedici mani d’artisti, venute da vicino e da lontano, hanno consegnato immagini alla città, così che il quotidiano potesse continuare a nutrirsi della presenza dell’arte. Un esperimento di comunità, un gesto che ha fatto rifiorire il terreno là dove crescevano i riti, ornare quelle nicchie era infatti un compito condiviso, una consuetudine che faceva del vicolo un corpo unico. Dalla voce delle narrazioni popolari e da una ricerca del 1992 fatta dai ragazzi di una scuola media, è rinata la memoria di questo tessuto minuto.

Si aggiunge oggi il segno, discreto e necessario, dell’artista per dare un respiro nuovo, la funzione di punto d’incontro, di presidio e protezione, di richiamo alla vicinanza e alla cura del bene comune. Passando per queste strade, lo sguardo incontra un segno che lo trattiene, un’immagine che chiede di connettersi con il luogo e non solo con gli occhi. Alla radice di questo progetto c’è la volontà di non chiudere il gesto dell’arte dentro cornici addomesticate, piuttosto l’opera si misura con la storia del territorio, legge ciò che è stato, ascolta ciò che è, immagina ciò che potrà venire. È un processo che va oltre la conservazione, oltre la tutela e la valorizzazione, un atto che attraversa, che unisce passato e futuro, e restituisce al presente la sua forza di comunità. In queste nicchie è stata depositata una costellazione di segni, alcuni interventi hanno scelto la via del simbolo primitivo con gesti che riportano l’edicola al suo principio e ad un’archeologia essenziale del sacro: non azione conclusa, ma apertura che lascia affiorare il possibile. Altri hanno dato voce al frammento e alla reliquia o a corpi che non celebrano, ma mostrano fragilità, gravità, caduta: il corpo stesso diventa “traccia”, segno di un passaggio che lascia memoria più che presenza. Qualcuno ha affidato la propria opera al linguaggio delle cose minute e dei silenzi eloquenti: un pozzo senza acqua, dove le monete restano sospese come desideri trattenuti o un altoparlante che non emette suono, cassa armonica muta che amplifica il vuoto e lo trasforma in materia. Sono gesti che mostrano “il senso nel suo farsi assente”, come direbbe Jean-Luc Nancy, perché è nell’intervallo, nel vuoto, che la comunità ritrova la sua forma. Poi c’è la via della fragilità e della tessitura, che riporta l’edicola all’intimità domestica. In certi interventi si avverte una voce femminile e corale che non si afferma come comando, ma si dischiude come relazione. Non è voce che pretende di possedere lo spazio, ma che lo apre, lo custodisce, lo offre all’ascolto e lo trasforma in dimora condivisa. E ancora, parola e riflesso hanno dato compimento a questo percorso: frasi elementari, simili a compiti di scuola, si trasformano in preghiere collettive, parole che tengono insieme le voci come in un coro. Davanti a uno specchio, invece, chi guarda incontra il proprio volto e riconosce che la pace non è un orizzonte lontano, ma una presenza riflessa e condivisa. Come scrive Walter Benjamin, “ogni specchio è anche una soglia”: in quel riflesso si apre lo spazio in cui individuo e comunità si rispecchiano l’uno nell’altro, scoprendosi parte dello stesso respiro.

Votiva ha ridato voce alle strade con segni discreti ma tenaci, facendo della pietra il linguaggio di una comunità che torna a guardarsi e a riconoscersi.

Parabita è un nome che non si lascia afferrare del tutto, come la linea d’ombra tra due tempi. Alcuni lo fanno risalire al latino para-bitam: “accanto alla vita”, oppure “oltre la forza”, evocando una geografia del margine, una soglia tra la sopravvivenza e la resistenza. Altri, più cauti, parlano di una voce antica, messapica forse, venuta da un tempo in cui i nomi non erano ancora parole, ma gesti nella pietra, impronte nella polvere. C’è chi dice che significhi “luogo benedetto”, rifugio nei secoli delle invasioni, città scavata per durare. O forse, più semplicemente ciò che resta quando la vita si ritira sottoterra per continuare altrove. Come accadeva, silenziosamente, nei frantoi ipogei. Nei secoli, queste architetture sotterranee, i cosiddetti trappeti, sono stati veri e propri santuari dell’economia contadina salentina e della Terra d’Otranto. Sotto terra, dove la roccia trattiene il caldo e il gelo, prendeva corpo l’olio lampante, fiumi di chiarore che dal ventre oscuro dei frantoi salivano e accendevano le città d’Europa. Non nasceva alla luce, ma nel fiato lento della pietra, in spazi scavati a misura di fatica. Le olive scendevano da un foro come offerte al buio e si raccoglievano nelle sciaghe, a fermentare, venti, trenta giorni, fino a trattenere quell’acidità che dava forza e spessore al loro dono. Poi il tempo della macina: la pasta, chiamata “mamma”, stretta tra i dischi, spinta da braccia e da animali, dal torchio colava un liquido doppio, acqua e olio insieme, accolto nel pozzo dell’angelo. Lì la natura separava i pesi: l’olio saliva, leggero, e mani pazienti lo raccoglievano con piatti di rame. Tre volte si torchiava la stessa pasta, fino a cavarne l’ultima stilla. L’acqua grassa scendeva invece nel pozzo della sentina, destinata a Marsiglia, a farsi sapone. L’olio, invece, restava in grandi pile di pietra, pronto a prendere il mare, a viaggiare verso le città del Nord, a farsi luce nei lampioni di Parigi, Vienna, Londra. Era un lavoro che consumava ossa e respiro, uomini e bestie insieme, chiusi nel ventre umido della terra da ottobre a marzo, condividevano il fiato, il sudore, la fatica. Pipe di erbe, a volte d’oppio, concedevano un attimo di tregua a corpi piegati.

Così, nel buio dei frantoi, si fabbricava la luce. Dal sottosuolo di Puglia saliva l’olio d’oro che accendeva il mondo: oro liquido nato nel silenzio, nel sacrificio, nella pazienza della pietra. Si scendeva per generare luce — l’olio era questo: combustione quieta, fuoco freddo, respiro delle lampade. Ma per produrlo, bisognava abitare il buio. Era necessario immergersi, trattenere il fiato, accettare il ritmo sotterraneo. Lì il lavoro diventava rito, il peso del corpo una misura dell’attesa. Francesco Arena, con la sua opera pensata per Ipogea, raccoglie proprio questo ritmo antico e lo restituisce non come documento, ma come risonanza. Non descrive, ma accorda. La Grotta (2025) non è dentro lo spazio: è lo spazio riattivato, ferito, ricucito dal gesto.

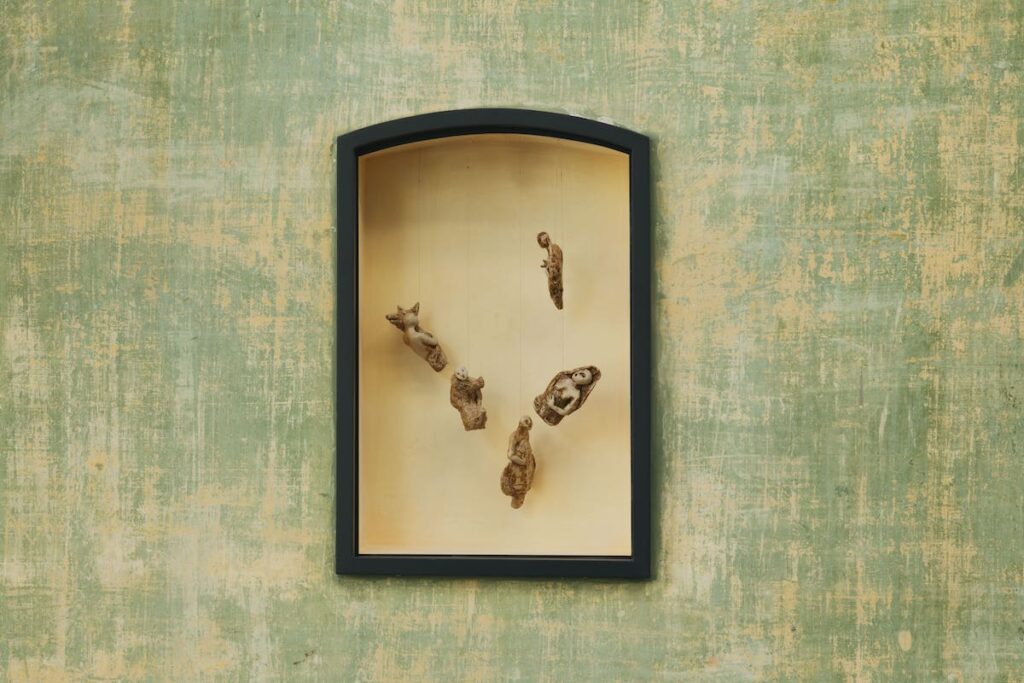

Il sottosuolo di Parabita è stratificato non solo da un punto di vista storico, ma anche simbolico. Oltre ai frantoi, le cripte e le cave, custodiva una delle scoperte archeologiche più importanti del Paleolitico italiano: la Grotta delle Veneri. Poco distante dal centro abitato, questa cavità naturale ha restituito nel 1965 due minuscole figure femminili scolpite su frammenti d’osso animale. Corpi pieni, senza volto, con fianchi larghi e seni prominenti: simboli arcaici di fertilità, sopravvivenze di un’umanità che modellava la vita con il gesto. Non mostrano, custodiscono. Hanno curve, silenzi, lentezza. Sono il corpo prima del corpo, la memoria fatta forma, la terra che sogna sé stessa. Non sappiamo chi le abbia scolpite né perché, ma il loro silenzio attraversa i millenni con la forza di ciò che non ha bisogno di spiegazioni. Quelle mani — anonime, antiche — non cercavano la bellezza, ma la durata.

È a questa memoria — geologica, produttiva, ancestrale — che Francesco Arena sembra attingere quando concepisce La Grotta. Due vasche di pietra leccese, un tempo destinate a trattenere l’olio, vengono innalzate, poste l’una di fronte all’altra come due presenze che si guardano. La loro verticalità sottrae la forma alla funzione: non più contenitori di lavoro e di fatica, ma soglie. Non si attraversano come oggetti, ma come varchi in cui lo sguardo è chiamato a misurarsi con la densità dell’interiorità. Arena non rappresenta i frantoi ipogei, per la maggior parte oggi inaccessibili, ne evoca invece la memoria attraverso la materia stessa che li compone: la pietra che conserva ancora l’impronta del sottosuolo, la sua durezza porosa, il suo respiro. La grotta, come il frantoio, è un luogo sottratto alla luce, una cavità di trasformazione: ventre oscuro che muta la sostanza e custodisce la memoria. La trama progettuale di IPOGEA non rinvia solo al sottosuolo, ma anche alla Grotta delle Veneri, da dove emersero quelle figure primordiali di fertilità. Dalla medesima pietra, dunque, un tempo nascevano immagini di vita; oggi, la pietra stessa si fa immagine, offrendosi come scena di contemplazione, in cui materia e pensiero si incontrano.

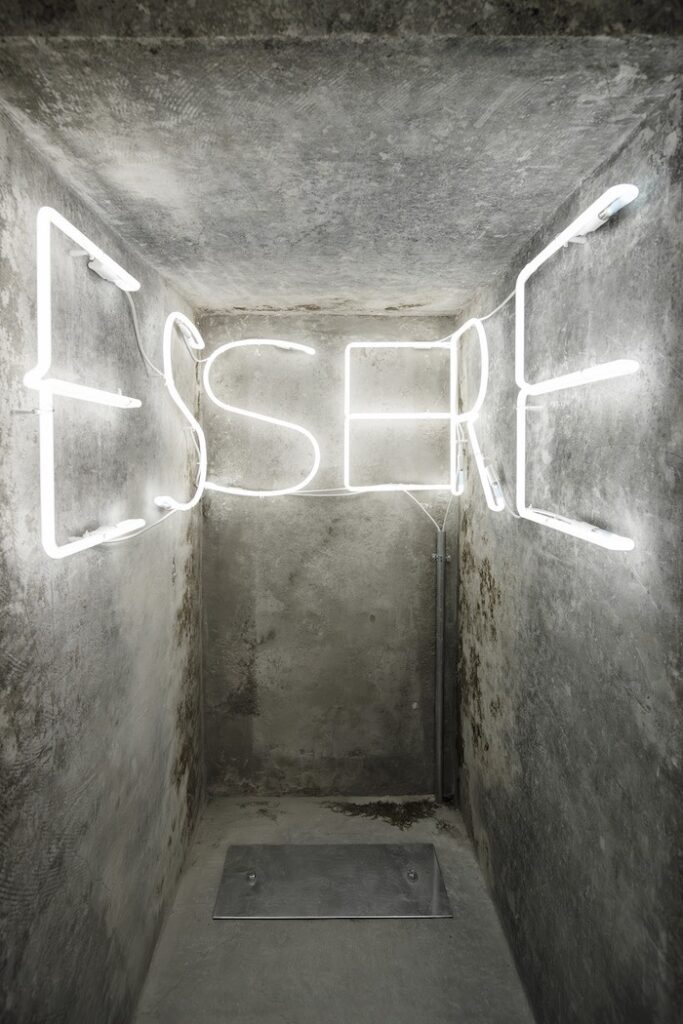

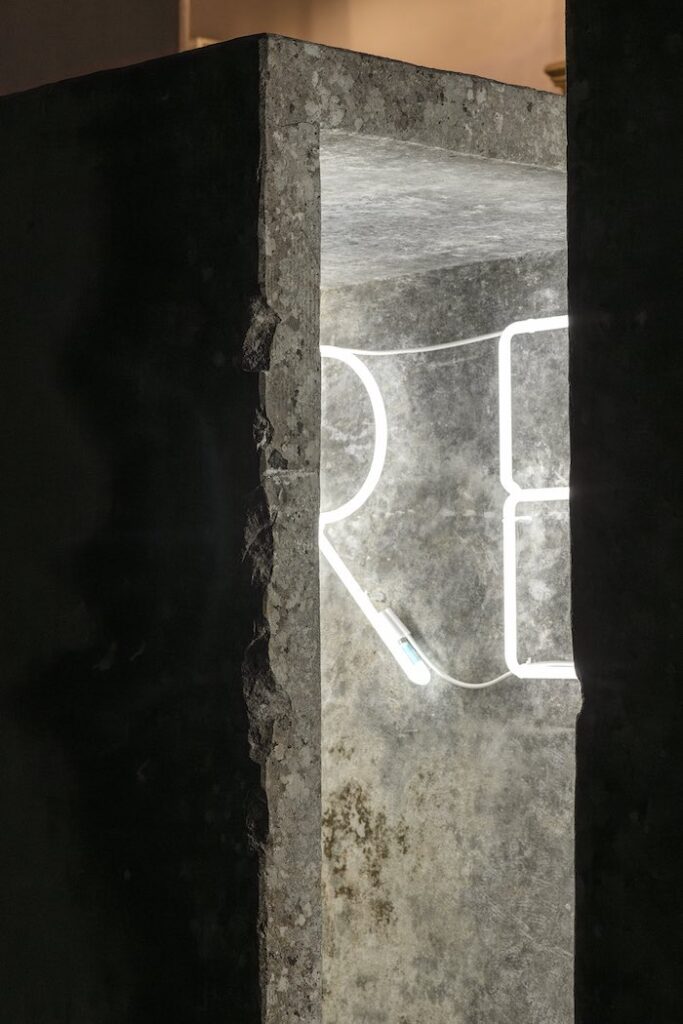

All’interno delle vasche due parole si accendono in neon: ESSERE e TEMPO. Separate, evocano la fragilità e l’eternità, lo scarto tra l’istante e l’assoluto. Unite, nominano la vita, fatta di esperienze, di storie, di incontri che si dissolvono e si rinnovano nel fluire inesorabile. Di notte, la luce non resta concetto ma diventa taglio, presenza, incisione nello spazio: un pensiero che brucia e illumina insieme.

Con Ipogea l’arte scende nel sottosuolo per restituirne il respiro. La pietra, che per secoli ha accolto il peso del lavoro e della memoria, si apre ora come soglia: non più deposito di fatica, ma luogo in cui il passato si converte in pensiero, e il pensiero si consegna al futuro. Francesco Arena è nato a Torre Santa Susanna, non lontano da qui. Il suo essere pugliese non è un dato biografico, ma una densità materiale. La sua pratica si nutre di terra, di peso, di assenza: misura lo spazio e il tempo attraverso la scala del corpo. La Grotta parla la lingua delle pietre, della gravina, del tempo inciso, in questo senso, un’opera cardinale: un punto da cui partire per comprendere una poetica della durata e della presenza. Entrare, sostare, ascoltare e uscire diversi. Con la polvere della pietra addosso, e un silenzio più grande nelle ossa.

Come ricorda il primo cittadino, Parabita per il contemporaneo non arresta il suo cammino. Porterà lo sguardo verso il margine, là dove il paesaggio si fa periferia, dove il periurbano traccia le sue fratture e il lontano si apre come frontiera. Urbana affronterà questa soglia fragile: tra l’inclinazione dell’uomo a disperdersi, ad allontanarsi dai suoi simili, e l’esigenza ostinata di ricondurre a centro ciò che oggi appare confine. E ancora, questo piccolo centro si doterà di un contenitore di mostre temporanee, luogo chiamato a farsi cuore pulsante di un fermento culturale incessante, spazio in cui la città potrà misurare il proprio respiro più ampio.

Con questa progettualità, Parabita si consegna al contemporaneo: radice che raccoglie memoria e comunità, vento che spinge oltre i confini. Nell’intreccio tra ciò che resiste e ciò che muove, la città riconosce la sua durata e consegna al futuro il proprio respiro.

VOTIVA e IPOGEA – Intervista a Stefano Prete, Sindaco di Parabita

Rita Selvaggio: Nel cuore del Salento, Parabita si fa teatro di un progetto che intreccia stratificazioni archeologiche e linguaggi contemporanei. In che modo la sua amministrazione ha immaginato questa coabitazione tra memoria e sperimentazione?

Stefano Prete: La nostra amministrazione ha voluto dare voce a una vocazione profonda di Parabita: quella di essere un luogo dove la memoria e la contemporaneità possano convivere e arricchirsi a vicenda. In un territorio segnato da millenni di storia, dalle tracce archeologiche del Paleolitico fino alle edicole votive del Novecento, abbiamo scelto di non limitare il patrimonio al solo racconto del passato, ma di attivarlo nel presente attraverso i linguaggi dell’arte contemporanea.

Progetti come VOTIVA e IPOGEA nascono da questa visione: mettere in dialogo il sacro e il popolare con la ricerca artistica più attuale, e i luoghi della memoria profonda – come gli ipogei e le grotte – con nuove forme espressive, partecipative e inclusive. Crediamo che sperimentare sul territorio non significhi stravolgerlo, ma dargli nuovi strumenti per raccontarsi, coinvolgendo cittadini, artisti e visitatori in un’esperienza viva e condivisa.

RS: L’intervento artistico permanente dialoga con luoghi segnati da una storia profonda — frantoi ipogei, grotte, nicchie votive. Ritiene che l’arte contemporanea possa diventare un dispositivo di risignificazione del paesaggio urbano e rurale, al di là della fruizione turistica?

SP: Assolutamente sì. Crediamo fortemente che l’arte contemporanea, se inserita in modo consapevole e rispettoso nel contesto, possa diventare un vero e proprio dispositivo di risignificazione del paesaggio – non solo urbano ma anche rurale e culturale. Nel caso di Parabita, i frantoi ipogei, le grotte e le nicchie votive non sono semplici fondali: sono spazi identitari, luoghi di memoria collettiva. L’intervento artistico non li “copre”, ma li attiva, li riapre a nuove interpretazioni, generando dialogo, ascolto e appartenenza.

Il nostro obiettivo non è mai stato quello di creare “decorazione” o attrazione turistica fine a sé stessa. Al contrario, vogliamo che l’arte diventi strumento di consapevolezza, di riflessione civica e di riappropriazione del territorio da parte della comunità. In questo senso, le opere permanenti non sono solo da guardare, ma da vivere, da attraversare e, soprattutto, da interrogare.

RS: Nel sostenere un progetto che non si limita a “decorare” lo spazio urbano ma lo interroga, lo attraversa, lei ha scelto una via difficile ma necessaria: quella dell’inquietudine fertile. Ritiene che sia ancora possibile una politica del senso, e non solo del consenso? E come si immagina una possibile pedagogia del guardare e dell’ascoltare in un tessuto urbano che cambia?

SP: Sì, credo sia non solo possibile, ma oggi urgente praticare una politica del senso. Una politica che non rincorra semplicemente il consenso immediato, ma che abbia il coraggio di seminare domande, anche scomode, generando quella che lei definisce giustamente “inquietudine fertile”.

Sostenere progetti come VOTIVA e IPOGEA significa, per un’amministrazione, scegliere la complessità. Significa rifiutare la superficie e puntare invece su percorsi che interrogano lo spazio pubblico, la storia, la spiritualità, l’identità collettiva. Non è una strada semplice, ma è quella che può produrre trasformazioni reali, durature, profonde.

Per quanto riguarda la “pedagogia del guardare e dell’ascoltare”, credo debba partire proprio da qui: dal mettere le persone in condizione di abitare lo spazio in modo nuovo, consapevole, non passivo. Non si tratta solo di educare a vedere l’arte, ma di educare a leggere il territorio come un linguaggio vivo, stratificato, che parla e chiede ascolto. Il cambiamento urbano non può essere solo fisico: deve essere culturale, relazionale, emotivo. Solo così potrà diventare anche politico – nel senso più alto e nobile del termine.

RS: Parabita per il Contemporaneo sembra evocare una “misura lenta del giorno”, una temporalità altra rispetto all’urgenza produttiva che domina l’agenda pubblica. Può la politica, secondo lei, farsi interprete di questa lentezza generativa?

SP: Parabita per il Contemporaneo nasce proprio dal desiderio di rallentare, di sottrarsi ai ritmi imposti dall’urgenza produttiva per dare spazio a processi profondi, partecipati, generativi. In un’epoca in cui tutto sembra dover essere immediato, misurabile e visibile, noi abbiamo scelto un’altra direzione: quella della cura, dell’ascolto e del tempo lungo.

Credo che sì, la politica possa – e debba – farsi interprete di questa lentezza. Non come resistenza nostalgica al cambiamento, ma come scelta consapevole di qualità, di profondità, di visione. In questo senso, Parabita per il Contemporaneo non è un evento, ma un processo. Un laboratorio civile dove l’arte non arriva dall’alto, ma si innesta nei tempi della comunità, ne rispetta i silenzi, i riti, le attese.

È una sfida politica nel senso più vero: mettere la cultura al centro come pratica trasformativa, anche quando non è redditizia nell’immediato, anche quando non produce numeri ma relazioni. Crediamo che la lentezza possa essere uno strumento di rigenerazione, non solo urbana, ma anche umana.

RS: Non si tratta soltanto di arte pubblica, ma di una forma di ascolto, quasi liturgica, del paesaggio. In che modo Parabita può diventare, anche simbolicamente, un laboratorio di coabitazione tra l’opera e la comunità, tra l’oltre e il quotidiano?

SP: Quello che stiamo costruendo con Parabita per il Contemporaneo va oltre l’idea di arte pubblica come semplice presenza estetica nello spazio. Parliamo di un ascolto profondo del paesaggio, quasi rituale, come lei suggerisce – un ascolto che tiene conto della storia, del vissuto, della sacralità diffusa che abita ogni angolo del nostro territorio.

Parabita può diventare un laboratorio simbolico e reale di coabitazione tra l’opera e la comunità, tra l’“oltre” dell’immaginazione e il “quotidiano” della vita locale. Lo può fare perché ha scelto di non separare cultura e cittadinanza, ma di provare ad intrecciarle, promuovendo il confronto.

La presenza di artisti come Michelangelo Pistoletto, con la sua Edicola del Canto della pace preventiva che intreccia il linguaggio della filastrocca con la poetica del caso, rappresentata dalla sfera di giornali, è emblematica: un segno che unisce gli opposti, che invita all’equilibrio, al dialogo. E questo è il senso più profondo del nostro progetto: fare in modo che l’arte non cali dall’alto, ma generi convivenza, cura, consapevolezza. Non monumenti da contemplare, ma spazi da vivere insieme.

RS: Ha parlato, in diverse occasioni, della volontà di lasciare un segno. Ma qui, più che un segno, sembra emergere un respiro: qualcosa che resta nel tempo perché non grida. È questa, forse, la sua idea di eredità politica?

SP: Sì, credo sia proprio così. Più che lasciare un segno visibile o immediato, vorrei lasciare un respiro: qualcosa che continua nel tempo senza bisogno di clamore, che si trasmette in silenzio, attraverso la qualità delle relazioni, dei luoghi, dei gesti. L’eredità politica, per me, non coincide con l’effimero dell’annuncio o dell’opera compiuta, ma con la capacità di attivare processi che proseguano anche oltre il mandato. Se oggi Parabita ospita opere che non solo si vedono ma si vivono, se i cittadini cominciano a riconoscersi in un linguaggio nuovo, aperto, plurale, allora forse stiamo costruendo qualcosa che dura.

La cultura – intesa come cura, come ascolto, come costruzione collettiva di senso – è il respiro lungo della politica. È la sua dimensione più umana, e allo stesso tempo più resistente. Se questo rimane, anche nel tempo, allora sì: possiamo parlare di eredità.

RS: Il Sud, e in particolare il Salento, è spesso raccontato attraverso stereotipi di luce e folklore. Qui invece si sono scelti il sottosuolo, l’ombra, la profondità. Cosa comporta, dal punto di vista amministrativo e simbolico, ribaltare così radicalmente l’immaginario dominante?

SP: Ribaltare l’immaginario dominante significa scegliere consapevolmente di non aderire a una narrazione comoda, fatta di luce, folklore e consumo veloce del territorio, ma di andare in profondità, letteralmente e metaforicamente. Scegliere il sottosuolo, le grotte, l’ombra, come nel progetto IPOGEA, è stato un atto politico prima ancora che culturale. Ha significato valorizzare ciò che non si vede subito, ciò che chiede attenzione, ascolto, lentezza. È un modo per affermare che il Sud non è solo superficie da ammirare, ma anche stratificazione, silenzio, complessità.

Raccontare il Salento da sotto, non da sopra, significa ridare dignità a una storia lunga, fatta anche di fatica e di invisibilità, e costruire una nuova immagine del territorio: meno cartolina, più coscienza.

RS: Ogni progetto lascia, se è vero, una scheggia di tempo dentro chi lo attraversa. C’è qualcosa — un dettaglio, uno sguardo, una parola incontrata in questo percorso con l’arte — che sente già come parte della sua personale eredità, anche se la strada amministrativa è ancora in cammino?

SP: Più che un gesto o una parola sola, è la somma degli sguardi che ho incrociato durante questo percorso: quelli dei cittadini che, magari con iniziale diffidenza, si sono avvicinati alle opere e hanno cominciato a riconoscervi qualcosa di familiare. Il modo in cui alcune persone hanno iniziato a raccontare i luoghi del progetto come “loro”, a portarci figli, amici e conoscenti. O degli artisti che hanno accolto il nostro territorio non come semplice scenografia, ma come luogo vivo da ascoltare e abitare.

Un dettaglio che mi ha colpito, e che sento già parte della mia eredità personale, è stato vedere un’anziana signora avvicinarsi all’edicola di Claudia Losi mentre installavamo il lavoro e lamentarsi del colore di fondo che avevamo predisposto. È tornata in casa e ne è riuscita con in mano un vecchio almanacco, che ha poi sfogliato con le curatrici fino a quando non ha trovato un riferimento cromatico che la soddisfaceva. Inutile dire che, in seguito, appena ne abbiamo avuto la possibilità, in accordo con l’artista abbiamo ridipinto il fondo con il colore scelto dalla signora in questione.

Momenti come questi non si registrano nei bilanci o nei verbali del Consiglio comunale, ma costruiscono la verità più profonda di un mandato pubblico. Quando accadono, capisci che la politica non è solo amministrare risorse, ma anche proteggere significati.

Cover: Helena Hladilová, Kaya, 2022. Marmo rosso antico. Foto Ilenia Tesoro

The Slow Measure of the Day – Parabita for the Contemporary

Parabita lies at the far south of the south, on the stony back of Apulia, sloping towards the sea like an animal at rest. It is there, between the Ionian coast that shimmers in the distance and the karst interior that swallows the light, that the town stretches itself, silent, like a vein of shadow in the flesh of the Salento. It is not on the sea, yet it feels the sea’s breath. It is not inland, yet it withdraws, as silence does when it is truly heard. Parabita is closer to stone than to air, nearer to memory than to the present. It is a geography of subtraction—hollowed, tenacious. It stands both above and below at once: resting on the calcareous spine of the Serra, yet with roots that sink into cold chambers, into tunnels, into fissures of time.

Seek it on the maps and you will find it between Gallipoli and Tuglie, between Matino and Alezio. But for those who listen to the South as if it were a body, Parabita is that point where breath halts for an instant and time turns vertical. Here hands once worked the rock as if it were bread, and light learned how to enter with modesty. It is a lesson in duration: here history is not measured in jolts but in strata, where darkness is never barren but a womb preparing, and in the stone that harbours and safeguards, the community still recognises itself and discovers, even now, its inheritance of the future.

Parabita for the Contemporary is a gaze that gathers together the roots and the time to come. It does not weigh richness in possessions, but in the traces that endure, the thoughts that ignite, the marvels that still astonish. It is a sign that holds us back from habit, reminding us that art can still make community.

In 2024 Votiva set out on this path, allowing the sacred shrines to mark the way. Where once a flower, a candle, a whispered prayer were left, there now opens a space for another gesture: that of art, which continues to safeguard and to transform.

From an idea by Mayor Stefano Prete, curated by Flaminia Bonino and Laura Perrone and under the artistic direction of Giovanni Lamorgese, Votiva is not simply a collection of public art. It is breath returned to stone, an ember rekindling the alleyways. Not a gathering of works alone, but of memory’s fragments, pulsing again within those sacred shrines, surfacing like veins of rock through the weave of Parabita.

In ancient Rome, the aedicula was a house in miniature. Two columns, a pediment, a shadow at the centre: enough to say that the divine could dwell beside the human. No distance between temple and street, between the atrium of a domus and the corner of an alley where, within the measure of a niche, the cosmos could be held. To pass by such a shrine was to walk past a held breath. The Lares, guardian deities of crossroads, passages and thresholds, and the Penates, gods of hearth and provision, kept company with the traveller and shielded the home. Not the immense, but the small—the cosmos folded into the crack of a wall: at the crossing of a street, on the threshold between night and return. A light was enough. A flower was enough. The god remained near, domestic, fragile as an expectation never wholly fulfilled.

Mircea Eliade would have called them “centres of the sacred,” small breaches where the eternal flares into the profane, apparitions of meaning. Not meaning completed, but its making and unmaking between a painted image and the wall that bears it. In their slight endurance, these roadside altars embody what Georges Didi-Huberman has seen in images: the power to smoulder within time, to shine like fireflies stubborn in the dark. They hold figures that are not dead relics, but sparks binding past and present. They are devices that and keep a presence otherwise fugitive—little theological engines in which the community still recognises its fragility and its waiting.

In the city, the aedicula is an heterotopia: an other-place, set into the run of the street and yet held apart from it. A fissure interrupting the rhythm of the road, reminding each passer-by that there is always a beyond, another elsewhere. So too the votive shrines of Parabita: living tesserae, their Genius Loci is still that power to root a community in space and time, in what resists anonymity. Francesco Arena, Chiara Camoni, Ludovica Carbotta, Claire Fontaine, Gianni Dessi, ektor garcia, Helena Hladilova, Felice Levini, Claudia Losi, K.R.M. Mooney, Liliana Moro, Adrian Paci, Mimmo Paladino, Michelangelo Pistoletto, Luigi Presicce, Namsal Siedlecki: sixteen artists’ hands, from near and far, have entrusted images to the town, so that the everyday might continue to feed on the presence of art.

It is an experiment in community, a gesture that made the ground bloom again where rituals once grew—for adorning those niches was once a shared task, a custom that made the alleyway into a single body. From the voice of popular tales, and from a 1992 school project by local children, the memory of this fine-grained fabric has returned. Today, added to it is the artist’s mark—discreet, necessary—bringing a new breath, the function of a meeting-place, of vigil and protection, of reminder to stay near and tend the common good.

Walking these streets, the eye meets a sign that halts it, an image that asks not only to be looked at, but to connect with the place itself. At the root of this project lies the will not to close the gesture of art within domesticated frames, but to let the work reckon with the history of the land, read what has been, listen to what is, and imagine what may yet come. It is a process that goes beyond conservation, beyond protection and valorisation: an act that traverses, that binds past and future, and restores to the present its strength as community. Within these niches a constellation of signs has settled. Certain offerings have chosen the path of the primitive symbol, with gestures that return the shrine to its origin and to an essential archaeology of the sacred: not a completed act, but an opening that allows the possible to surface. Others have given voice to the fragment and the relic, or to bodies that do not celebrate but reveal fragility, gravity, fall: the body itself becomes “trace,” the mark of a passage that leaves memory more than presence.

Some artists have entrusted their works to the language of small things and eloquent silences: a well without water, where coins remain suspended like held-back desires; or a loudspeaker that emits no sound, a mute sounding box that amplifies emptiness and turns it into matter. These are gestures that make visible “meaning in its becoming absent,” as Jean-Luc Nancy would say, for it is in the interval, in the void, that the community regains its form.

Then there is the path of fragility and weaving, returning the shrine to domestic intimacy. In some works, one senses a female, choral voice, not asserting itself as command but unfolding as relation. It is not a voice that claims possession of space, but one that opens it, guards it, offers it to listening, and transforms it into a shared dwelling.

And again, word and reflection have brought this journey to completion: elementary phrases, like school exercises, become collective prayers, words that bind voices together like a chorus. In front of a mirror, instead, the viewer meets their own face and recognises that peace is not a distant horizon but a reflected and shared presence. As Walter Benjamin writes, “every mirror is also a threshold”: in that reflection opens the space where individual and community mirror one another, discovering themselves as part of the same breath.

Votiva has given voice back to the streets through signs discreet yet tenacious, making of stone the language of a community learning once more to look at itself and to recognise itself.

Parabita is a name that cannot be wholly grasped, like the line of shadow between two times. Some trace it back to the Latin para-bitam: “beside life,” or “beyond strength,” evoking a geography of the margin, a threshold between survival and resistance. Others, more cautious, speak of an ancient tongue, perhaps Messapic, from a time when names were not yet words but gestures in stone, imprints in dust. There are those who say it means “blessed place,” a refuge in centuries of invasions, a city carved out to endure. Or perhaps, more simply, what remains when life withdraws underground in order to continue elsewhere. As it once did, silently, in the hypogeal oil mills.

Over centuries these subterranean architectures—the so-called trappeti—were true sanctuaries of the peasant economy of Salento and of Terra d’ Otranto. Below ground, where rock kept back heat and cold, lamp oil took form: rivers of brightness rising from the dark belly of the mills to flow across Europe. It was not born into the light, but in the slow breath of stone, in spaces carved to the measure of toil. The olives fell through a shaft like offerings to the dark, gathered in pits where they fermented for twenty, thirty days, until they held the acidity that gave their gift its strength and weight.

Then came the time of the press: the paste, called “mother,” wedged between the millstones, driven by arms and by animals, yielding a double liquid, water and oil together, poured into the “angel’s well”. There nature separated the weights: oil rose, light, and patient hands gathered it with copper plates. Three times the same paste was pressed, until the last drop was drawn. The fatty water flowed into the sump, destined for Marseille to be made into soap. The oil remained in great stone cisterns, ready to take the sea, to travel north, to become light in the streetlamps of Paris, Vienna, London.

It was work that consumed bone and breath. Men and beasts together, shut in the damp belly of the earth from October to March, shared the same air, the same sweat, the same strain. Pipes of herbs, sometimes of opium, gave bent bodies a brief reprieve. Thus, in the dark of the mills, light was made. From the subsoil of Apulia rose the oil that lit the world: liquid gold born of silence, of sacrifice, of the patience of stone. One descended in order to generate light—the oil was this: a quiet combustion, a cold fire, the breath of lamps. But to produce it, one had to inhabit the dark. It was necessary to immerse oneself, to hold breath, to accept the subterranean rhythm.

There work became ritual, the weight of the body a measure of waiting. Francesco Arena, with his work conceived for Ipogea, gathers precisely this ancient rhythm and returns it not as document but as resonance. He does not describe, but attunes. La Grotta (2025) is not within the space: it is the space itself reawakened, wounded, stitched back together by the gesture.

The subsoil of Parabita is layered not only historically but symbolically. Beyond the oil mills, crypts and quarries, it guarded one of the most important archaeological discoveries of the Italian Paleolithic: the Grotta delle Veneri. Just outside the town, this natural cavity yielded in 1965 two tiny female figures carved on fragments of animal bone. Full-bodied, faceless forms, with broad hips and prominent breasts: archaic symbols of fertility, survivals of a humanity that shaped life with gesture. They do not display, they preserve. They have curves, silences, slowness. They are the body before the body, memory given form, the earth dreaming of itself. We do not know who carved them or why, but their silence crosses millennia with the force of what has no need of explanation. Those hands—anonymous, ancient—were not seeking beauty, but endurance.

It is to this memory—geological, productive, ancestral—that Francesco Arena seems to turn in conceiving La Grotta. Two basins of Lecce stone, once used to hold oil, are raised up, set facing each other like two presences in mutual regard. Their verticality releases the form from function: no longer containers of labour and fatigue, but thresholds. They are not crossed as objects but as passages where the gaze is summoned to measure itself against the density of interiority.

Arena does not represent the hypogeal mills, most of them today inaccessible, but instead evokes their memory through the very material that composes them: the stone that still carries the imprint of the subsoil, its porous hardness, its breath. The cave, like the oil mill, is a place withheld from the light, a cavity of transformation: a dark womb that alters substance and safeguards memory.

The vision of Ipogea refers not only to the subsoil but also to the Grotta delle Veneri, where those primordial figures of fertility once emerged. From the same stone, then, images of life were once born; today, the stone itself becomes image, offering itself as a scene of contemplation, where matter and thought meet.

Inside the basins two words flare in neon: BEING and TIME. Apart, they evoke fragility and eternity, the rift between the instant and the absolute. Together, they name life itself, made of experiences, of stories, of encounters that dissolve and are renewed in ceaseless flow. By night, the light is no longer concept but incision, presence, a cut into space: a thought that burns and illuminates at once.

With Ipogea, art descends into the subsoil to return its breath. The stone that for centuries bore the weight of labour and of memory now opens as threshold: no longer a depository of fatigue, but a place where the past is transfigured into thought, and thought is handed on to the future.

Francesco Arena was born in Torre Santa Susanna, not far from here. His being Apulian is not a biographical fact, but a material density. His practice feeds on earth, on weight, on absence: it measures space and time through the scale of the body. La Grotta speaks the language of stones, of ravines, of time engraved. In this sense, it is a cardinal work: a point of departure for understanding a poetics of duration and presence.

To enter, to linger, to listen, and to leave changed. With the dust of stone upon the skin, and a greater silence in the bones.

As the mayor recalls, Parabita for the Contemporary does not halt its path. It will turn its gaze toward the margin, where the landscape becomes periphery, where the peri-urban draws its fractures and the distant opens as frontier. Urbana will face this fragile threshold: between humanity’s inclination to scatter, to drift away from its own kind, and the stubborn need to bring back to the centre what today appears as boundary.

And further still, this small town will equip itself with a space for temporary exhibitions, a place destined to become the beating heart of an unceasing cultural ferment, a space where the city will be able to measure its wider breath.

With this vision taking shape, Parabita entrusts itself to the contemporary: root that gathers memory and community, wind that drives beyond borders. In the weave between what endures and what moves, the city recognises its own duration and delivers to the future its breath.

An interview with Stefano Prete, Mayor of Parabita

Rita Selvaggio: In the heart of Salento, Parabita becomes the stage for a project that intertwines archaeological stratifications with contemporary languages. How has your administration envisioned this coexistence between memory and experimentation?

Stefano Prete. Our administration sought to give voice to a profound vocation of Parabita: to be a place where memory and contemporaneity can coexist and enrich one another. In a land marked by millennia of history—from the archaeological traces of the Paleolithic to the votive shrines of the twentieth century—we chose not to confine heritage to a mere narration of the past, but to activate it in the present through the languages of contemporary art.

Projects such as VOTIVA and IPOGEA arise from this vision: to set the sacred and the popular in dialogue with the most current artistic research, and to connect sites of deep memory—such as hypogea and caves—with new expressive, participatory, and inclusive forms. We believe that experimenting on the territory does not mean distorting it, but rather offering it new tools to narrate itself, engaging citizens, artists, and visitors alike in a living, shared experience.

RS: The permanent artistic intervention enters into dialogue with sites imbued with a profound history—underground olive presses, caves, votive niches. Do you believe contemporary art can become a device for re-signifying the urban and rural landscape, beyond mere tourist consumption?

SP: Absolutely. We firmly believe that contemporary art, when introduced consciously and respectfully into its context, can become a genuine device for the re-signification of the landscape—not only urban, but also rural and cultural.

In Parabita’s case, the underground olive presses, the caves, and the votive niches are not mere backdrops: they are spaces of identity, places of collective memory. The artistic intervention does not “cover” them but activates them, reopening them to new interpretations and generating dialogue, listening, and belonging. Our goal has never been to create “decoration” or tourist attractions for their own sake. On the contrary, we want art to become a tool of awareness, civic reflection, and reappropriation of the territory by the community. In this sense, the permanent works are not only to be looked at, but to be lived, traversed, and, above all, questioned.

RS: In supporting a project that does not simply “decorate” urban space but questions it, traverses it, you have chosen a difficult yet necessary path: that of fertile disquiet. Do you believe it is still possible to pursue a politics of meaning, and not merely of consensus? And how do you envision a possible pedagogy of seeing and listening within an urban fabric in transformation?

SP: Yes, I believe it is not only possible, but today urgent, to practice a politics of meaning. A politics that does not simply chase immediate consensus, but that has the courage to sow questions—even uncomfortable ones—thus generating what you aptly call a “fertile disquiet.”

Supporting projects such as VOTIVA and IPOGEA means, for an administration, choosing complexity. It means rejecting superficiality and instead investing in paths that interrogate public space, history, spirituality, and collective identity. It is not an easy road, but it is the one that can bring about real, lasting, profound transformations.

As for the “pedagogy of seeing and listening,” I believe it must begin precisely here: by putting people in a position to inhabit space in a new, conscious, and non-passive way. It is not only about educating people to look at art, but about educating them to read the territory as a living, stratified language—one that speaks and demands to be listened to.

Urban change cannot be merely physical: it must be cultural, relational, emotional. Only then can it also become political—in the highest and noblest sense of the term.

RS: Parabita per il Contemporaneo seems to evoke a “slow measure of the day,” a temporality that stands apart from the productive urgency dominating the public agenda. In your view, can politics embody this generative slowness?

SP: Parabita per il Contemporaneo was born precisely from the desire to slow down, to withdraw from the rhythms imposed by productive urgency in order to give space to processes that are deep, participatory, and generative. At a time when everything seems to have to be immediate, measurable, and visible, we chose another direction: that of care, of listening, of extended time.

I do believe politics can—and must—become an interpreter of this slowness. Not as a nostalgic resistance to change, but as a conscious choice for quality, depth, and vision. In this sense, Parabita per il Contemporaneo is not an event, but a process. A civic laboratory where art does not arrive from above, but is grafted onto the rhythms of the community, respecting its silences, its rituals, its expectations.

It is a political challenge in the truest sense: placing culture at the center as a transformative practice, even when it is not immediately profitable, even when it does not produce numbers but relationships. We believe slowness can be a tool of regeneration—not only urban, but human.

RS: This is not merely about public art, but about a form of listening—almost liturgical—to the landscape. How can Parabita become, even symbolically, a laboratory of cohabitation between the work and the community, between the “beyond” and the everyday?

SP: What we are building with Parabita per il Contemporaneo goes beyond the idea of public art as a mere aesthetic presence in space. It is about a profound, almost ritual listening to the landscape—as you suggest—a listening that takes into account history, lived experience, and the diffuse sacrality that inhabits every corner of our territory.

Parabita can become both a symbolic and concrete laboratory of cohabitation between the work and the community, between the “beyond” of imagination and the “everyday” of local life. It can do so because it has chosen not to separate culture from citizenship, but to weave them together, fostering encounter.

The presence of artists such as Michelangelo Pistoletto, with his Edicola del Canto della pace preventiva, intertwining the language of nursery rhyme with the poetics of chance embodied in a sphere of newspapers, is emblematic: a sign that unites opposites, that calls for balance, for dialogue. And this is the deepest meaning of our project: to ensure that art does not descend from above, but generates coexistence, care, and awareness. Not monuments to be contemplated, but spaces to be lived together.

RS: On several occasions you have spoken of the wish to leave a mark. Yet here, more than a mark, what seems to emerge is a breath: something that endures in time precisely because it does not shout. Is this, perhaps, your idea of political legacy?

SP: Yes, I believe it is precisely so. Rather than leaving a visible or immediate mark, I would like to leave a breath: something that continues over time without the need for clamor, transmitted in silence through the quality of relationships, places, and gestures.

For me, political legacy does not coincide with the ephemeral nature of announcements or accomplished works, but with the ability to activate processes that continue even beyond one’s mandate. If today Parabita hosts works that are not only seen but lived, if citizens begin to recognize themselves in a new, open, and plural language, then perhaps we are building something that lasts.

Culture—understood as care, as listening, as the collective construction of meaning—is the long breath of politics. It is its most human dimension, and at the same time its most resilient. If this remains, enduring in time, then yes: we can speak of legacy.

RS: The South, and Salento in particular, is often narrated through stereotypes of light and folklore. Here, instead, you have chosen the underground, the shadow, depth. What does it mean, from an administrative and symbolic point of view, to so radically overturn the dominant imaginary?

SP: To overturn the dominant imaginary means to consciously choose not to conform to a comfortable narrative—one made of light, folklore, and the rapid consumption of the territory—but instead to go in depth, both literally and metaphorically.

Choosing the underground, the caves, the shadow—as in the IPOGEA project—was a political act before it was a cultural one. It meant giving value to what is not immediately visible, what demands attention, listening, slowness. It is a way of affirming that the South is not only a surface to be admired, but also stratification, silence, complexity. To recount Salento from below, not from above, means restoring dignity to a long history made also of labor and invisibility, and constructing a new image of the territory: less postcard, more consciousness.

RS: Every project, if it is true, leaves a shard of time within those who pass through it. Is there something—a detail, a gaze, a word encountered in this journey with art—that you already feel as part of your personal legacy, even though your administrative path is still ongoing?

SP: More than a single gesture or word, it is the sum of the gazes I have met along this journey: those of citizens who, perhaps with initial diffidence, approached the works and began to recognize in them something familiar. The way some people started to speak of the project’s sites as “theirs,” bringing children, friends, acquaintances. Or the artists who welcomed our territory not as a mere backdrop, but as a living place to listen to and inhabit.

One detail that struck me, and that I already feel as part of my personal legacy, was seeing an elderly woman approach Claudia Losi’s shrine while we were installing the work, and complain about the background color we had prepared. She returned home and came back holding an old almanac, which she leafed through with the curators until she found a chromatic reference that satisfied her. Needless to say, soon after, as soon as we were able, we repainted the background with the color chosen by that very woman, in agreement with the artist.

Moments like these are not recorded in budgets or in the minutes of the City Council, yet they shape the deepest truth of a public mandate. When they occur, you realize that politics is not only about administering resources, but also about protecting meanings.

Cover: Helena Hladilová, Kaya, 2022. Marmo rosso antico. Foto Ilenia Tesoro