English version below —

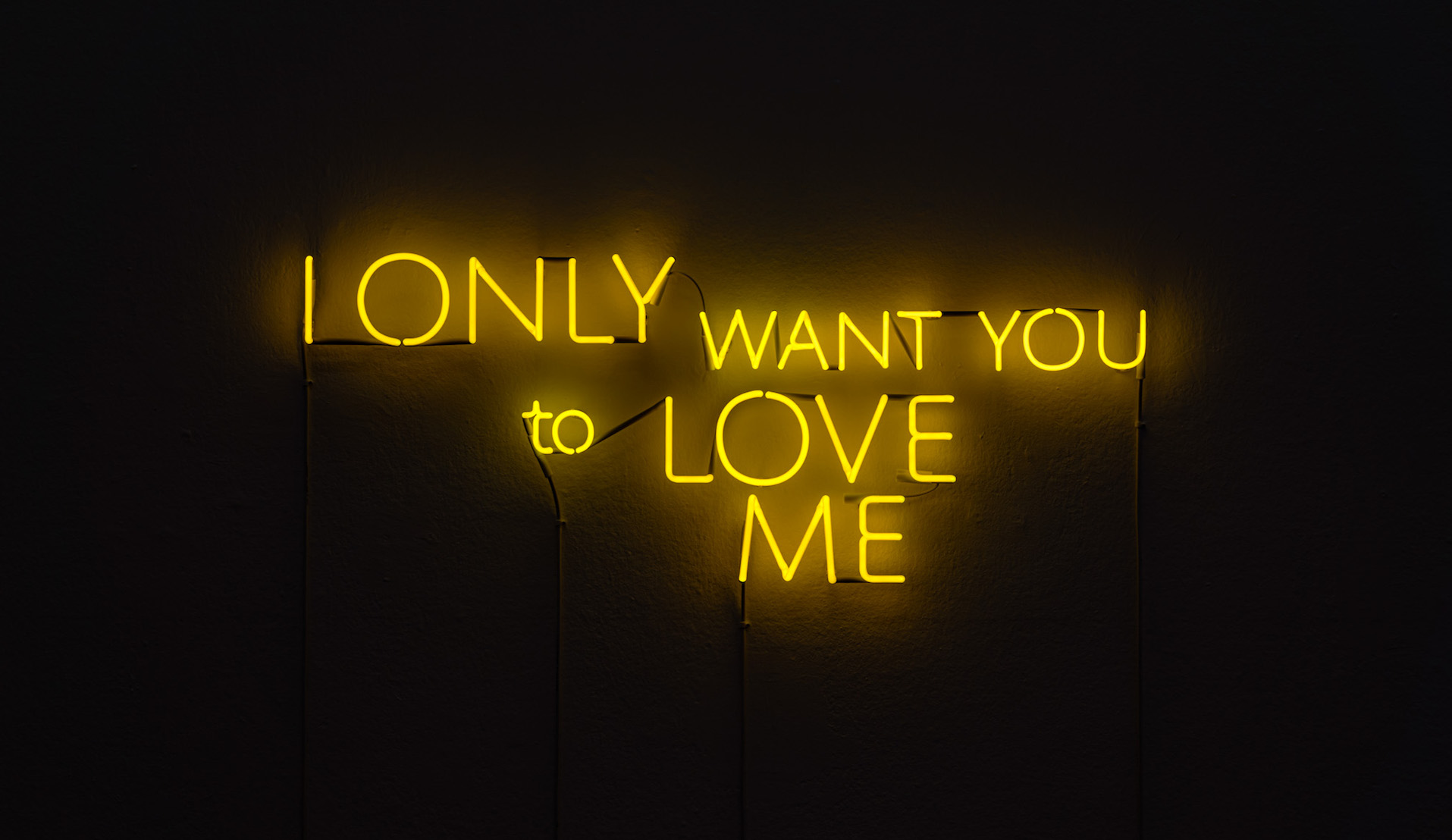

Al PAC Padiglione d’Arte Contemporanea di Milano, I Only Want You To Love Me, prima antologica italiana dedicata al duo italo-americano Lovett/Codagnone, si offre come un duplice spazio: archivio di corpi messi in tensione e campo minato di desideri insubordinati.

Curata da Diego Sileo e realizzata in collaborazione con Participant Inc di New York, la mostra attraversa oltre vent’anni di pratiche che intrecciano amore e potere, mettendo in scena il corpo come teatro di disciplina e di rischio, vulnerabile ma ostinatamente aperto al possibile. Promosso dal Comune di Milano e prodotto dal PAC e da Silvana Editoriale, il progetto espositivo (4 luglio-14 settembre 2025) è dedicato alla memoria di Alessandro Codagnone.

Ci sono mostre che si visitano come si sfoglia un archivio, altre come si percorre un campo minato. La retrospettiva che il PAC di Milano dedica a Lovett/Codagnone è entrambe le cose: un archivio di corpi messi in tensione, di icone deposte e desideri insorti, ma anche un terreno carico di dispositivi, dove ogni passo può far detonare una domanda inattesa sul nostro stare al mondo.

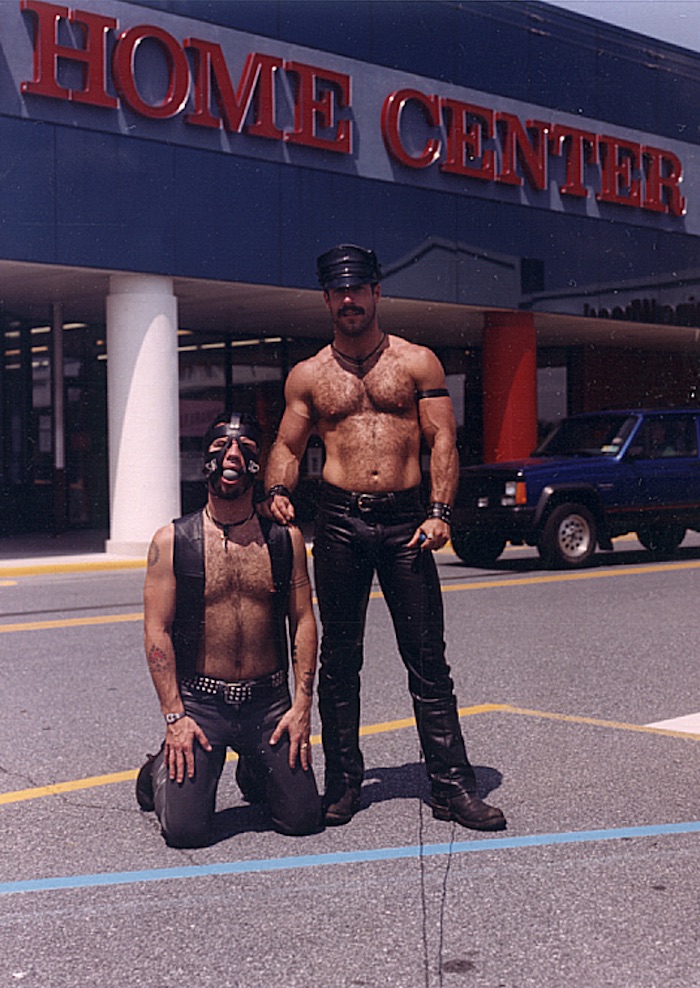

La pratica di John Lovett e Alessandro Codagnone — duo artistico attivo tra New York e l’Europa dagli anni Novanta fino alla morte di Codagnone nel 2019 — nasce da un’urgenza profondamente corporale e insieme teorica: interrogare come il potere attraversi i corpi, li disciplini, li erotizzi, li renda insieme oggetti e vettori di senso. Influenzati tanto dal linguaggio visivo del post-minimalismo quanto dalle sottoculture BDSM, costellazioni erotico-politiche che si articolano attorno a pratiche consensuali di dominio e sottomissione, dove la relazione è già una grammatica del potere, dal teatro della crudeltà di Artaud e dai codici della cultura queer, i due hanno costruito negli anni un corpus di lavori che funziona come un atlante delle microfisiche del potere.

Fondato nel 1995, il loro sodalizio è stato al tempo stesso artistico e sentimentale, e ha portato alla presentazione delle loro opere in istituzioni internazionali come il New Museum e il MoMA PS1 di New York, l’ICA di Philadelphia, l’ICA di Boston e il Museo Marino Marini di Firenze.

In fotografie, video, installazioni performative, Lovett/Codagnone hanno messo in scena il corpo come territorio governato, superficie dove si imprimono norme di genere, desideri devianti, violenze rituali — ma anche come luogo di riscatto, di sperimentazione, di rovesciamento inatteso.

Nel 2008 hanno anche fondato- la band musicale Candidate con il musicista Michele Pauli, già membro dei Casino Royale: un’ulteriore estensione della loro pratica artistica nella dimensione sonora e performativa.

È qui che il lavoro della curatela si rivela decisivo: questa mostra milanese non si limita a ordinare cronologicamente opere e documenti, ma le orchestra in un percorso drammaturgico che sfrutta le volumetrie e le soglie del PAC per trasformare il museo stesso in un dispositivo foucaultiano. Corridoi che diventano corridoi disciplinari, sale bianche che si offrono come camere rituali, superfici vetrate che riflettono e moltiplicano lo sguardo, costringendo lo spettatore a misurarsi con la propria presenza, il proprio corpo, le proprie posture. L’architettura razionale e trasparente del PAC, quasi confessoriale, amplifica questo gioco di esposizioni e sorveglianze, facendosi complice del dispositivo estetico che la mostra mette in atto.

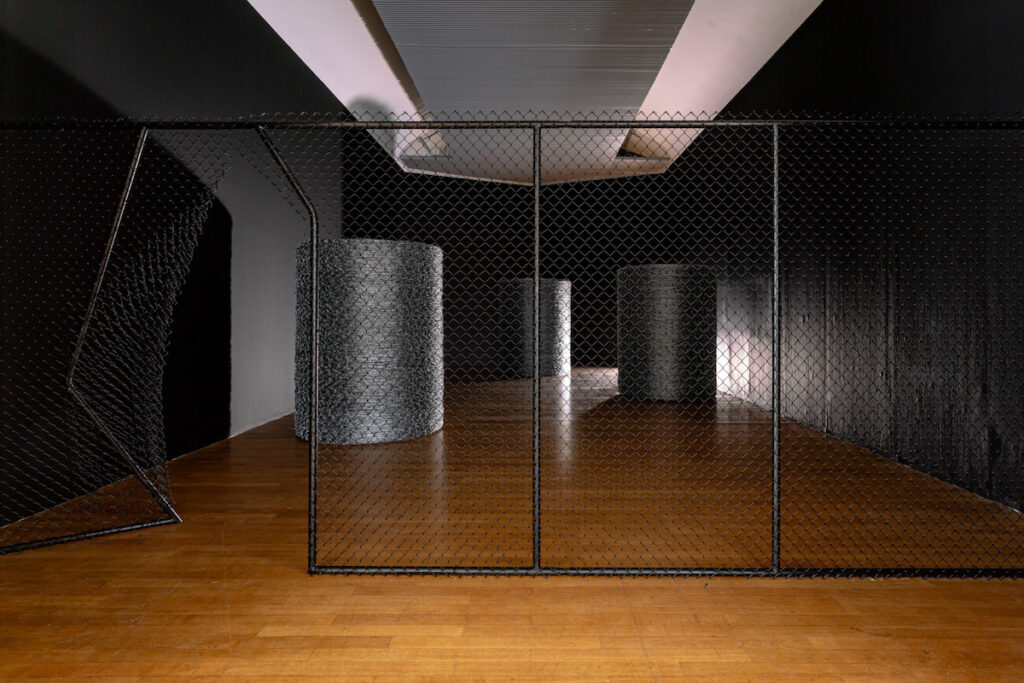

Il percorso include opere storiche come Greetings (1996), Stripped (2006), Love Vigilantes (2007), Truth Is Born of the Times, not of Authority (2012), una delle opere più emblematiche dell’estetica resistente di Lovett/Codagnone. Il titolo, tratto da un frammento attribuito a Bertolt Brecht, instaura fin da subito un cortocircuito tra temporalità e verità, tra evento e enunciazione politica. L’ampia installazione si presenta come un ambiente sonoro e visivo: una struttura delimitata da rete metallica e filo spinato — materiali di confine, di esclusione, di guerra — dentro cui risuonano voci che recitano frammenti di testi storici e teatrali, componendo una partitura dissonante e ininterrotta. Lì dove altri avrebbero costruito una scenografia ideologica, Lovett/Codagnone espongono un vuoto performativo, un luogo che si fa cassa di risonanza per discorsi disallineati, per ciò che è stato detto ai margini, in tempi sospesi, lontano dalle grammatiche del potere. La verità, suggeriscono, non è mai una proprietà di chi comanda: essa sorge dal kairos, dal tempo opportuno, dal trauma e dalla lotta.

Nel contesto della mostra, questa installazione funziona come nervatura politica dell’intero percorso espositivo. A differenza di altre opere più segnate dalla componente performativa o affettiva, qui la tensione si fa secca, strutturale, quasi documentaria. Eppure il dispositivo non si limita a denunciare: invita, piuttosto, a sostare nell’ambiguità della testimonianza, ad abitare quella zona in cui la parola – dissidente, teatrale, dolente – può ancora fendere l’aria e rendere instabile l’architettura della norma. Il corpo è assente, ma la sua eco permane. Il recinto metallico, più che imprigionare, disegna un teatro della soglia: un varco dove la memoria storica si intreccia alla performatività del linguaggio, e dove la voce si riappropria dello spazio politico attraverso l’eco.

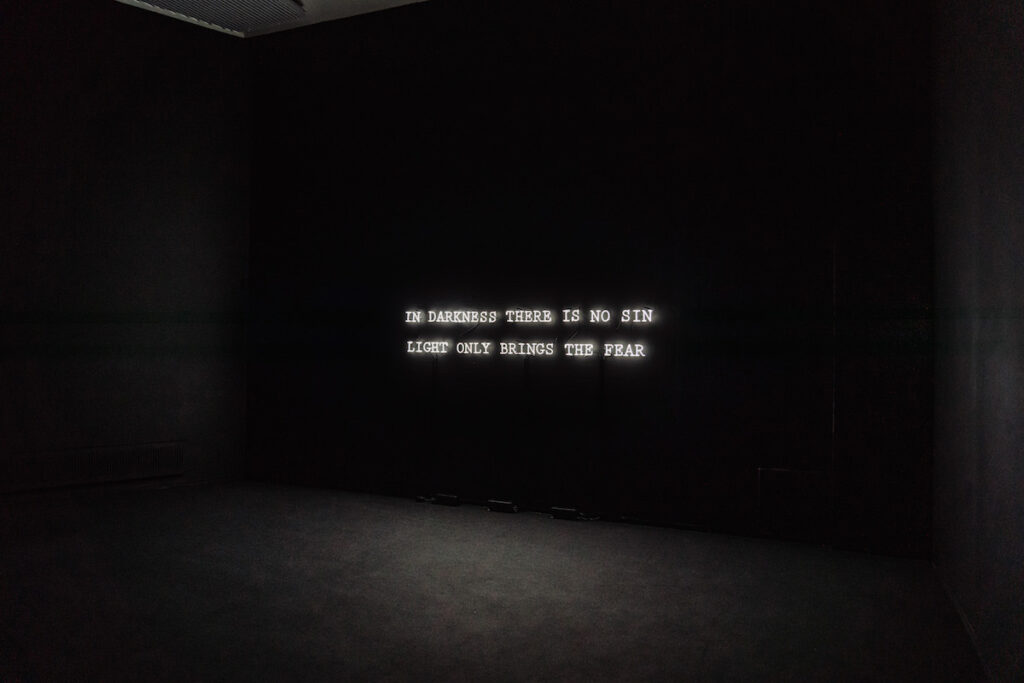

In mostra figurano anche lavori recentissimi come In Darkness There Is No Sin / Light Only Brings the Fear (2025), prodotto appositamente per l’occasione. Quest’opera emerge infatti come frammento latente di un pensiero in attesa, rintracciato dal curatore Diego Sileo all’interno dell’archivio digitale di Alessandro Codagnone: una cartella di appunti, visioni e intenzioni progettuali non ancora prodotte, custodite come ciò che resta in potenza, ciò che avrebbe potuto essere. La decisione di produrlo in seno a questa mostra, non equivale a una semplice restituzione memoriale, ma si configura come un gesto di attivazione differita, che interroga la co-autorialità come forma persistente di presenza. Nell’opera — pensata da uno ma ora realizzata nella continuità viva del duo — si compie un atto di fedeltà e di trasformazione: un dispositivo di luce che non rievoca soltanto, ma rilancia, come se il progetto stesso si riaccendesse nella relazione tra chi non c’è più e chi continua ad abitare la scena, a darvi corpo, voce e decisione.

In questa soglia tra archivio e attualizzazione, tra assenza e azione, In the darkness there is no sin, light only brings the fear opera come un’intermittenza: non solo luce, ma intervallo; non solo memoria, ma ritorno del possibile. Il titoloriprende un verso del brano Wait for the Blackout (1980) della band post-punk britannica The Damned, tra i pionieri di quell’estetica cupa e ambivalente che avrebbe anticipato il gothic e influenzato profondamente l’immaginario queer contemporaneo. Lontano dall’essere un semplice omaggio culturale, si fa piuttosto enunciato critico, condensando una poetica dell’oscurità come spazio di protezione, latenza e desiderio. Ma la citazione non si limita a un gesto evocativo: essa attiva una riflessione politica sullo statuto dello sguardo, della visibilità e del desiderio. In questa prospettiva, la pratica di Lovett / Codagnone si iscrive nella costellazione teorica delineata da José Esteban Muñoz, per il quale la soggettività queer si situa non tanto nell’evidenza del presente, quanto in una dimensione altra, progettuale, utopica. L’oscurità evocata non è dunque negazione, ma apertura: condizione di possibilità in cui il soggetto può sottrarsi alle grammatiche normate della visibilità e articolare una presenza altra, ancora in divenire. In the darkness there is no sin, il buio diviene luogo di rifugio e di insorgenza: spazio in cui il desiderio si libera dal dispositivo normativo della luce, e in cui la paura non è assenza di controllo, ma sintomo di una soggettività che eccede il visibile. Il blackout non è una sospensione, ma un gesto affermativo: una modalità di esistenza non ancora pienamente realizzata, ma già in potenza — come quella stessa promessa queer che, secondo Muñoz, “exists as the illumination of a then and there.”

Fra le opere più emblematiche, Stripped (2006) ci accoglie all’inizio del percorso come un monito funebre: una bandiera americana annerita, spogliata delle stelle e delle strisce, trasformata in una sorta di sudario funebre. Qui il potere si rivela nella sua dimensione simbolica: la bandiera come dispositivo che unifica, normalizza, produce identità collettive, ma Lovett/Codagnone la sabotano, la spogliano, la fanno marcire nel nero, come a suggerire che perfino i dispositivi simbolici più radicati possono essere disattivati o ri-funeralizzati.

In questa forma di iconoclastia sommessa, ritroviamo la stessa poetica del rischio e dell’alterazione che Preciado individua nella soggettività farmaco-pornografica: anche l’identità nazionale, come quella sessuale o di genere, può essere hackerata, denudata, ridotta a un tessuto vuoto su cui inscrivere altre storie.

Ancora più radicale nel convocare il desiderio come gesto politico è Love Vigilantes (2007): un’installazione di specchi neri incisi con citazioni di Hakim Bey, il teorico delle TAZ (Temporary Autonomous Zones).Tali frammenti testuali non operano come mere citazioni, ma sono atti di sabotaggio poetico: trappole verbali disseminate a minare l’ordine simbolico che invocano zone temporanee di libertà in cui l’amore e il desiderio si organizzano come forme di insurrezione.

Pubblicato nel 1991, il libro di Bey — al secolo Peter Lamborn Wilson — è un manifesto anarchico che propone la creazione di spazi effimeri e autogestiti, liberi dal controllo statale e dalle logiche capitalistiche. In questa visione, l’arte non è decorazione ma strumento tattico, e le “zone autonome” sono momenti di intensità in cui le relazioni si fanno erotiche, rituali, sovversive. È proprio questo orizzonte che Love Vigilantes evoca, facendo del riflesso specchiante una soglia fra visibile e occulto, tra controllo e diserzione. Qui, lo spazio riflette lo spettatore ma lo restituisce come residuo ambiguo, avvolto in parole che parlano di micro-rivolte del piacere.

Se Foucault ci ha insegnato a leggere il corpo come terreno di esercizio del potere, e Paul B. Preciado ci invita a concepirlo come una soft technology hackerabile, Lovett/Codagnone con Love Vigilantes offrono una sorta di atlante delle fughe minime, dove il desiderio si fa strategia di sabotaggio. L’eros non è solo un contro-potere: è un rituale di riappropriazione che trasforma il museo in una camera oscura per nuove alleanze fra corpi, segni, riflessi.

Questa stessa tensione fra disciplina e rischio, fra controllo e insurrezione, torna nei nuovi interventi pensati per il PAC come ad esempio nella serie di billboards disseminati nella città, che contaminano lo spazio della comunicazione di massa con messaggi ambivalenti.

Drift (2012), concepito nel 2012 come intervento pubblico per i billboards dello spazio urbano di Palermo utilizza invece fotografie stampate in grande formato, scattate tra Europa e Stati Uniti. Sono accompagnate da citazioni musicali che, distorcendo o amplificando il messaggio, rievocano la strategia di sovversione dei codici del marketing per generare nuove forme di disidentificazione collettiva. È come se gli artisti traslocassero la loro pratica performativa dal corpo alla città, trasformando l’orizzonte urbano in una TAZ effimera, un luogo di apparizioni brevi, non catalogabili. In un’epoca in cui l’identità è mercificata attraverso le immagini e la sessualità regolata da protocolli biochimici e mediatici, questi lavori si offrono come zone contrasessuali, piccole faglie dove si disattivano i comandi della norma.

In parallelo alla mostra, il PAC attiva una Project Room intitolata Matrimoni imperfetti, curata da Giulia Zompa e dedicata all’archivio della Galleria Emi Fontana (1992–2009), figura chiave della scena milanese e sostenitrice del duo sin dagli esordi. Non un semplice omaggio, ma una genealogia affettiva e curatoriale, un ritorno al luogo della nascita in cui la complicità tra artista e gallerista si rivela come forma di co-scrittura: un’alleanza imperfetta, ma necessaria. Le immagini, le locandine, la corrispondenza epistolare non restituiscono solo un passato: lo trattengono, lo fanno vibrare come una tensione ancora presente.

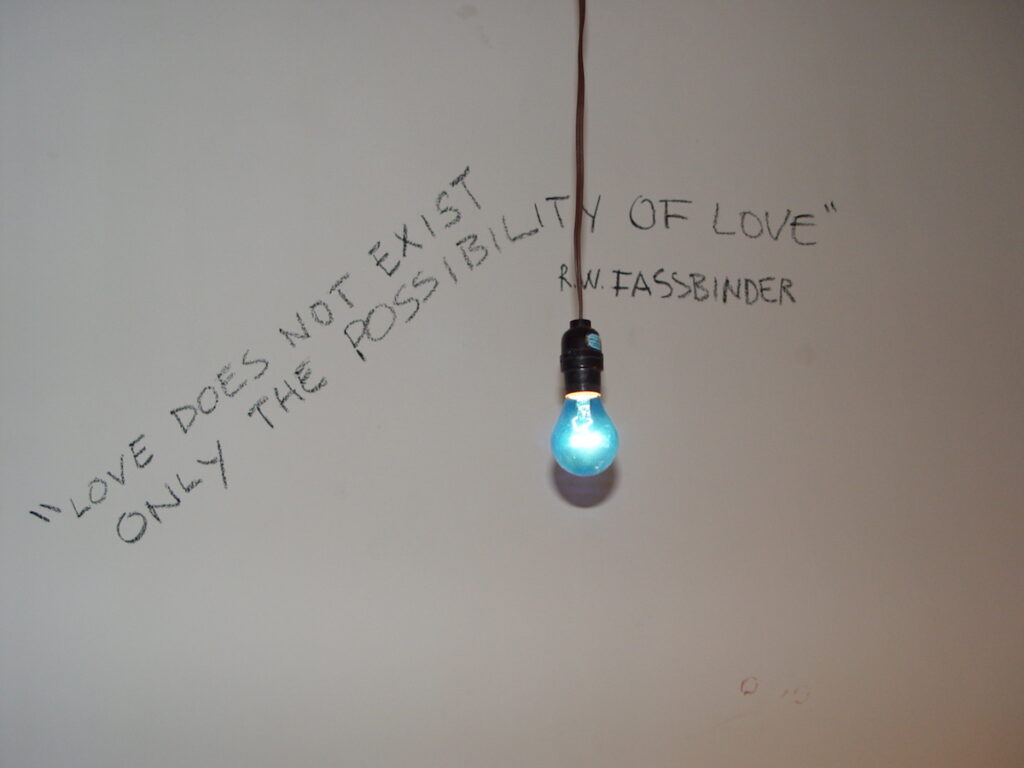

A espandere ulteriormente il campo della mostra interviene anche il public program, che include una rassegna cinematografica dedicata a Rainer Werner Fassbinder presso la Cineteca Milano e una performance teatrale del collettivo Phoebe Zeitgeist, Se si ha l’amore in corpo non serve giocare al flipper. Quest’ultima, concepita come gesto site-specific, evoca la presenza del regista tedesco come spettro sentimentale e politico, attraversandone i temi — il desiderio, la dipendenza, la crudeltà amorosa — e restituendoli in forma di drammaturgia frammentata, lirica, in dialogo diretto con le installazioni di Lovett/Codagnone.

In questa fitta trama di linguaggi — tra cinema, teatro e archivio — ogni gesto si fa medium di una continuità queer che non si chiude nel tempo dell’evento ma insiste, trapassa, contamina. Una linea d’ombra che attraversa le opere, i corpi e i documenti come una corrente clandestina di desiderio: sotterranea, ma ostinata, capace di rilanciare la politica dei legami come atto critico e come promessa.

La mostra al PAC è qualcosa di più di un omaggio antologico: si rivela come un cantiere aperto di nuove politiche del corpo, dove la vulnerabilità non è solo ferita ma anche forza di disarmo, dove il desiderio non è semplice piacere ma tattica critica, insurrezione minima, persino clandestina.

Lovett/Codagnone ci mostrano che nessun corpo è mai davvero concluso, che ogni identità è un palinsesto riscrivibile e che, come ricordava Foucault, là dove il potere stringe più forte si aprono varchi di resistenza inattesa.

O forse, per usare le parole stesse di Hakim Bey incise nel nero, “It is precisely in the shadows that the secret kingdoms of possibility are born”.

Cover: Lovett Codagnone, I ONLY WANT YOU TO LOVE ME. PAC Milano – Foto Nico Covre

I Only Want You to Love Me

Text by Rita Selvaggio —

At the PAC – Padiglione d’Arte Contemporanea in Milan, I Only Want You To Love Me, the first Italian retrospective dedicated to the Italo-American duo Lovett/Codagnone, unfolds as a dual space: an archive of bodies drawn into tension, and a minefield of insubordinate desires.

Curated by Diego Sileo and realised in collaboration with Participant Inc. in New York, the exhibition spans more than twenty years of practices that entangle love and power, staging the body as a theatre of discipline and risk — vulnerable, yet obstinately open to the possible. Promoted by the City of Milan and produced by PAC together with Silvana Editoriale, the project (4 July–14 September 2025) is dedicated to the memory of Alessandro Codagnone.

There are exhibitions one visits as one leafs through an archive, and others one walks through like a minefield. The retrospective that PAC dedicates to Lovett/Codagnone is both: an archive of strained bodies, deposed icons, and insurgent desires — but also a terrain dense with dispositifs, where every step may trigger an unexpected question about how we inhabit the world.

The practice of John Lovett and Alessandro Codagnone — an artistic duo active between New York and Europe from the 1990s until Codagnone’s death in 2019 — arose from an urgency that was at once deeply corporeal and theoretical: to interrogate how power traverses bodies, disciplines them, eroticises them, rendering them both objects and vectors of meaning.

Influenced as much by the visual language of post-minimalism as by BDSM subcultures — erotic-political constellations structured around consensual practices of domination and submission, where the relation itself is already a grammar of power — as well as by Artaud’s theatre of cruelty and the codes of queer culture, the two artists constructed over the years a body of work that operates as an atlas of the microphysics of power.

Founded in 1995, their partnership was both artistic and romantic, and led to the presentation of their works in major international institutions such as the New Museum and MoMA PS1 in New York, the ICA in Philadelphia and Boston, and the Museo Marino Marini in Florence.

Through photographs, videos, and performative installations, Lovett/Codagnone staged the body as a governed territory — a surface inscribed with gender norms, deviant desires, ritualized violences — but also as a site of redemption, of experimentation, of unexpected reversal.

In 2008, they also founded the band Candidate, together with musician Michele Pauli — a former member of Casino Royale — as a further extension of their artistic practice into the sonic and performative dimension.

It is here that curatorial work proves decisive: this Milanese exhibition does not merely arrange works and documents in chronological order, but orchestrates them into a dramaturgical itinerary, one that exploits the volumes and thresholds of PAC to transform the museum itself into a Foucauldian dispositif. Corridors become disciplinary corridors; white rooms offer themselves as ritual chambers; glass surfaces reflect and multiply the gaze, forcing the viewer to confront their own presence, their body, their posture. The rational, transparent architecture of PAC — almost confessional in nature — amplifies this play of exposures and surveillance, becoming an accomplice to the aesthetic dispositif enacted by the exhibition.

The path includes historical works such as Greetings (1996), Stripped (2006), Love Vigilantes (2007), and Truth Is Born of the Times, not of Authority (2012), one of the most emblematic expressions of Lovett/Codagnone’s aesthetics of resistance. The title, drawn from a fragment attributed to Bertolt Brecht, immediately establishes a short-circuit between temporality and truth, between event and political utterance. The large-scale installation unfolds as a visual and sonic environment: a structure enclosed by barbed wire and metal fencing — materials of borders, exclusion, and war — within which voices resound, reciting fragments of historical and theatrical texts, composing a dissonant, uninterrupted score.

Where others might have built an ideological scenography, Lovett/Codagnone expose instead a performative void: a space that becomes a resonance chamber for dissonant discourses, for what was spoken on the margins, in suspended times, far from the grammars of power.

Truth, they suggest, is never the property of those who rule: it arises from kairos, from the opportune moment, from trauma and from struggle. Within the exhibition’s context, this installation serves as the political spine of the entire parcours. Unlike other works more marked by performative or affective components, here the tension turns dry, structural, almost documentary. And yet, the dispositif does not settle for denunciation: it invites us to linger in the ambiguity of testimony, to inhabit that zone where speech — dissident, theatrical, grief-stricken — can still cleave the air and destabilize the architecture of the norm.

The body is absent, but its echo remains. The metal enclosure, more than imprisoning, draws the outline of a threshold theatre: an opening where historical memory intertwines with the performativity of language, and where voice reclaims the political space through reverberation.

At this threshold between archive and actualization, between absence and action, In the Darkness There Is No Sin / Light Only Brings the Fear operates as an intermittence: not only light, but interval; not only memory, but a return of the possible.

The title quotes a line from Wait for the Blackout (1980) by the British post-punk band The Damned — pioneers of that dark, ambivalent aesthetic that prefigured the gothic and profoundly shaped contemporary queer imaginaries. Far from a mere cultural homage, the citation becomes a critical enunciation, distilling a poetics of darkness as a space of protection, latency, and desire.

Yet the quote is not simply evocative: it activates a political reflection on the status of the gaze, of visibility, and of desire. In this light, Lovett/Codagnone’s practice inscribes itself within the theoretical constellation drawn by José Esteban Muñoz, for whom queer subjectivity is not anchored in the evidence of the present, but in an elsewhere — projective, utopian. The darkness evoked is thus not negation, but opening: a condition of possibility in which the subject may elude the normative grammars of visibility and articulate another presence, still in the making.

In the darkness there is no sin: darkness becomes a site of refuge and of insurgency — a space in which desire is released from the normative dispositif of light, and in which fear is not the absence of control, but the symptom of a subjectivity that exceeds the visible. Blackout, here, is not suspension, but an affirmative gesture: a mode of existence not yet fully realised, but already in potential — like that same queer promise which, as Muñoz writes, “exists as the illumination of a then and there.”

Among the most emblematic works, Stripped (2006) greets the viewer at the outset of the exhibition like a funerary warning: an American flag blackened, stripped of stars and stripes, transformed into a kind of mourning shroud.

Here, power reveals itself in its symbolic dimension: the flag as a dispositif that unifies, normalises, produces collective identities. Yet Lovett/Codagnone sabotage it, undress it, allow it to rot into blackness — as if to suggest that even the most deeply rooted symbolic dispositifs can be deactivated, or re-funeralised.

In this form of subdued iconoclasm, we encounter the same poetics of risk and alteration that Paul B. Preciado identifies in the pharmaco-pornographic subjectivity: even national identity, like sexual or gender identity, can be hacked, stripped bare, reduced to an empty fabric upon which other stories may be inscribed.

Even more radical in its invocation of desire as a political gesture is Love Vigilantes (2007): an installation of black mirrors etched with quotations from Hakim Bey, theorist of the TAZ — Temporary Autonomous Zones.

These textual fragments do not function as mere citations, but rather as acts of poetic sabotage: verbal traps scattered to undermine the symbolic order, invoking temporary zones of freedom in which love and desire are organised as forms of insurrection.

Published in 1991, Bey’s book — authored under the name Peter Lamborn Wilson — is an anarchist manifesto advocating for the creation of ephemeral, self-managed spaces free from state control and capitalist logics. In this vision, art is not ornament but tactical tool, and “autonomous zones” are moments of heightened intensity where relations become erotic, ritualistic, subversive.

It is precisely this horizon that Love Vigilantes evokes, transforming the mirrored reflection into a threshold between the visible and the occult, between control and desertion.

Here, space reflects the viewer — but returns them as an ambiguous residue, enveloped in words that speak of micro-rebellions of pleasure.

If Foucault taught us to read the body as a terrain of power’s exercise, and Paul B. Preciado urges us to conceive it as a hackable soft technology, then Lovett/Codagnone, with Love Vigilantes, offer something like an atlas of minor escapes, where desire becomes a strategy of sabotage.

Eros is not merely a counter-power: it is a ritual of reappropriation that turns the museum into a darkroom for new alliances between bodies, signs, and reflections.

This same tension between discipline and risk, between control and insurrection, reappears in the new interventions conceived for PAC — such as the series of billboards disseminated across the city, contaminating the space of mass communication with ambivalent messages.

Drift (2012), conceived as a public intervention for the billboards of Palermo’s urban space, deploys large-format photographs taken across Europe and the United States. These images are accompanied by musical quotations that, by distorting or amplifying the message, recall a strategy of subverting marketing codes in order to generate new forms of collective disidentification.

It is as if the artists had transposed their performative practice from the body to the city, transforming the urban horizon into an ephemeral TAZ — a site of brief, uncataloguable apparitions.

In an era in which identity is commodified through images and sexuality governed by biochemical and media protocols, these works propose themselves as contra-sexual zones — small fissures where the commands of the norm are suspended.

In parallel with the exhibition, PAC activates a Project Room entitled Imperfect Marriages, curated by Giulia Zompa and dedicated to the archive of Galleria Emi Fontana (1992–2009), a key figure of the Milanese scene and an early supporter of the duo.

Not a mere tribute, but an affective and curatorial genealogy: a return to the site of origin, where the complicity between artist and gallerist reveals itself as a form of co-authorship — an imperfect but necessary alliance. The images, posters, and epistolary exchanges do not merely reconstruct a past: they hold it, they make it vibrate as a tension still alive in the present.

Further expanding the scope of the exhibition is the public program, which includes a film series dedicated to Rainer Werner Fassbinder at Cineteca Milano and a theatrical performance by the Milan-based collective Phoebe Zeitgeist, If You Have Love in Your Body There’s No Need to Play Pinball.

Conceived as a site-specific gesture, the performance conjures the presence of the German director as both sentimental and political spectre, traversing his recurring themes — desire, dependency, the cruelty of love — and returning them in the form of a fragmented, lyrical dramaturgy, in direct dialogue with the installations of Lovett/Codagnone.

In this dense weave of languages — cinema, theatre, archive — every gesture becomes a medium of queer continuity, one that refuses to close within the temporality of the event, but persists, transits, contaminates.

A line of shadow runs through the works, the bodies, the documents — like a clandestine current of desire: underground, yet insistent, capable of reigniting the politics of relation as both critical act and promise.

The exhibition at PAC is more than an anthological homage: it unfolds as an open construction site for new politics of the body — where vulnerability is not merely a wound, but a force of disarmament; where desire is not simple pleasure, but critical tactic, minimal insurrection, even clandestine.

Lovett/Codagnone remind us that no body is ever truly finished, that every identity is a palimpsest to be rewritten, and that — as Foucault once observed — wherever power tightens its grip, unforeseen breaches of resistance may open.

Or perhaps, to borrow the words of Hakim Bey etched into the blackness: “It is precisely in the shadows that the secret kingdoms of possibility are born.”