English version below —

Con la mostra Chantal Akerman. Travelling, il Museu de Arte Contemporânea del Centro Cultural de Belém accoglie la terza e più atmosferica tappa di un percorso espositivo iniziato a Bruxelles e proseguito a Parigi. In ciascuna sede, l’opera di Akerman ha trovato una diversa eco architettonica e affettiva, adattandosi ai ritmi e ai vuoti degli spazi, come i suoi film si adattano alla lentezza delle camere fisse e alla geometria dei gesti quotidiani.

Il MAC/CCB non è uno spazio neutro: progettato da Vittorio Gregotti e Manuel Salgado, l’edificio è concepito come una sequenza di piazze interne, slarghi, corridoi che si aprono su cortili e squarci di luce. L’architettura, fatta di pietra chiara e volumi modulari, incorpora la temporalità dello sguardo: è uno spazio che costringe a rallentare, ad attraversare. A differenza delle sedi precedenti, dove prevalevano il rigore storiografico (a Bruxelles) o l’enfasi tematica (a Parigi), a Lisbona l’allestimento trova un contrappunto sensoriale nell’architettura stessa: gli spazi non chiudono le installazioni in cornici museali, ma le lasciano respirare. Il risultato è una forma espositiva che sembra replicare la grammatica del cinema di Akerman: pause, interstizi, silenzi che diventano attivi. Il visitatore è immerso in una dimensione percettiva in cui il tempo non avanza, ma si espande, non scorre, ma si dilata sospeso.

È la stessa Lisbona, con la sua luce obliqua e la sua architettura di margine, a offrire un contrappunto ideale al lavoro di Akerman. Città di partenze e ritorni, di transiti coloniali e malinconie atlantiche, Lisbona porta con sé una stratificazione storica in cui le tematiche del lutto, dell’assenza e dell’esilio trovano una risonanza profonda. È come se il paesaggio urbano, sospeso tra rovine e promesse, amplificasse la dimensione temporale e affettiva delle opere esposte.

A Bruxelles (Bozar), la mostra si configurava come un ritorno a casa: un museo della memoria con la chiarezza cronologica di un archivio critico. A Parigi (Jeu de Paume), si mettevano in rilievo i legami con l’avanguardia femminista, la diaspora ebraica, il cinema sperimentale americano. A Lisbona, l’allestimento dialoga con l’architettura aperta del MAC/CCB: la mostra diventa spazio esperienziale, in cui il “travelling” del titolo si manifesta come postura esistenziale. Qui l’opera si slega dal tempo biografico e si fa materia, montaggio lento di assenze e Akerman, che ha sempre filmato confini, si rivela come cartografa del limite.

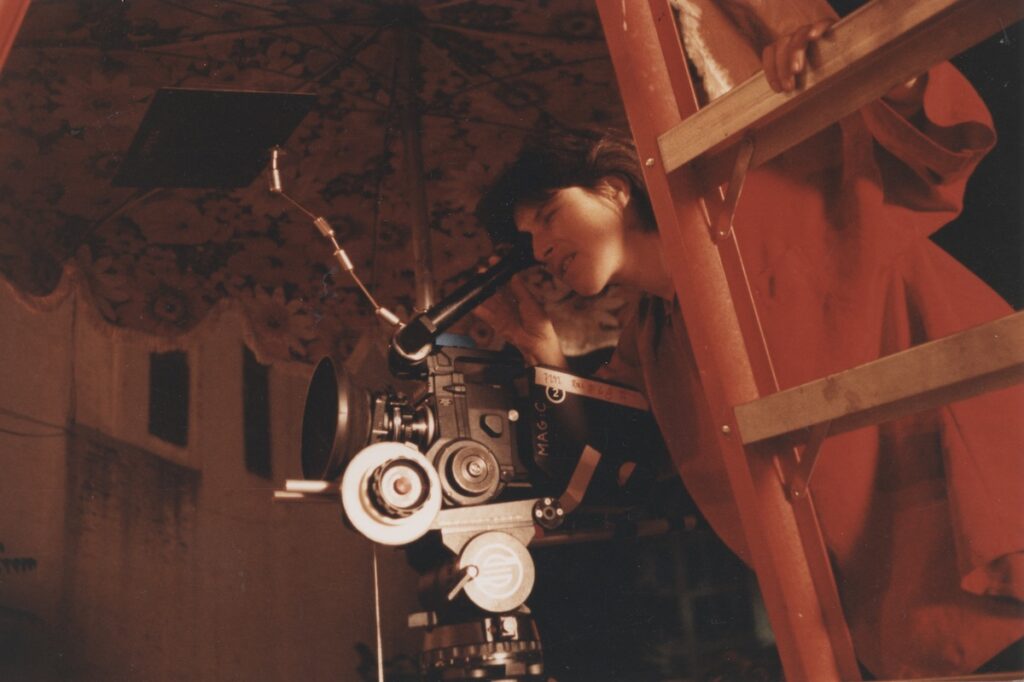

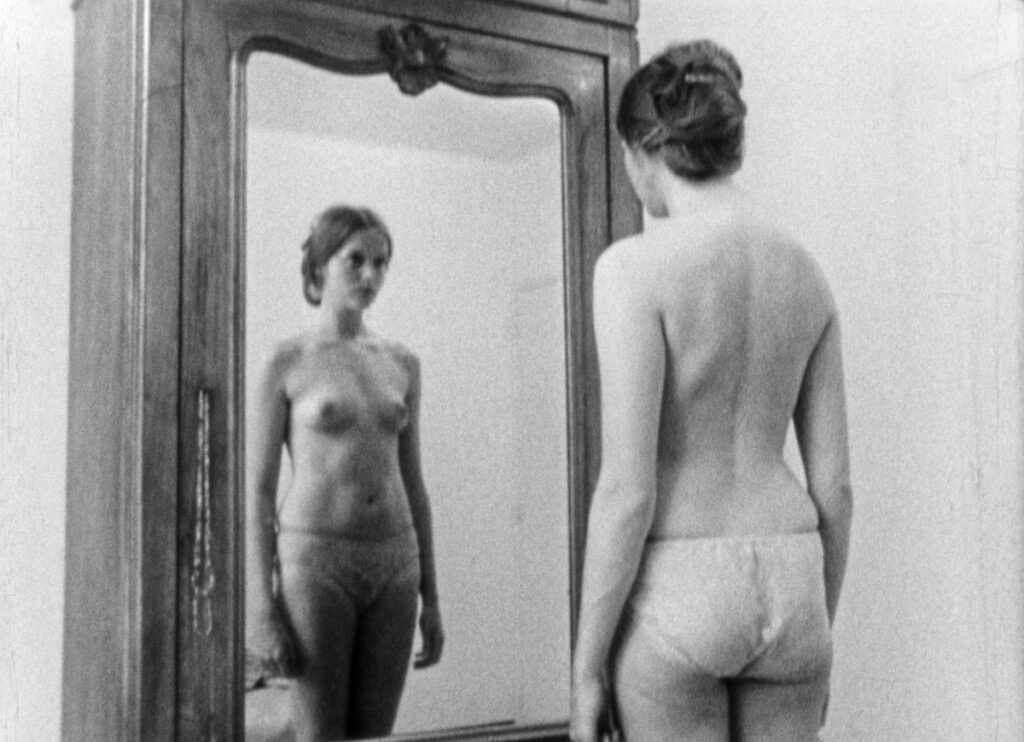

ll percorso espositivo si apre con Saute ma ville (1968), opera fondativa e insieme detonatore simbolico dell’intera costellazione Akermaniana. Non si tratta soltanto di un debutto: è una soglia, un prologo esplosivo che annuncia, in forma germinale e già radicale, il linguaggio visivo e concettuale che attraverserà tutta l’opera successiva. Girato a soli diciotto anni, il film è infatti un cortocircuito poetico e premonitore. Un’opera di rottura — nel senso più letterale e simbolico del termine. Dura poco più di dieci minuti, ma contiene già, in forma embrionale e violenta, molte delle ossessioni che attraverseranno tutto il lavoro dell’artista: il corpo femminile confinato, la casa come spazio claustrofobico, la ripetizione dei gesti, il tempo che implode, la relazione perturbante con la madre, il silenzio che urla.

Akerman è davanti e dietro la camera. Entra in un appartamento, sigilla le finestre, accende il gas, canticchia, si trucca, pulisce, si accanisce contro gli oggetti della quotidianità. In un crescendo surreale, la cucina — spazio domestico e femminile per eccellenza — diventa il teatro di una combustione lenta e inesorabile. Alla fine, l’esplosione. Fuori campo.

Il film si chiude su un nero, come un presagio. E oggi, diventa impossibile non leggerlo anche come un’intuizione tragica, una profezia inquieta. Saute ma ville non è solo un gesto proto-femminista, né solo una performance esistenziale: è una dichiarazione di poetica fatta col corpo.

Akerman mette in scena, con un’ironia atroce e infantile, il paradosso del soggetto che cerca di sfuggire all’ordine — domestico, narrativo, simbolico — che lo opprime. Ma la fuga non è mai totale. Il gesto estremo, la distruzione, diventa un modo per occupare lo spazio. Per lasciare una traccia. Un buco.

Come ha scritto l’artista stessa, anni dopo:

“Il mio lavoro non è che una lunga storia d’amore con mia madre, e con le madri.”

E forse Saute ma ville è il primo capitolo di quel romanzo muto: un grido che attraversa le mura della casa, un atto d’amore e di violenza insieme, la fondazione di un linguaggio visivo che da subito rifiuta l’ornamento, l’illusione, la narrazione.

È un cinema che scoppia — e nella sua deflagrazione, si inaugura.

Una delle forze di questa mostra lisboeta è quella di riconoscere che il lavoro di Akerman non è solo cinema, ma una forma d’abitare: abitare il tempo, abitare il trauma, abitare la lingua. In questo senso, le installazioni video come Woman Sitting After a Killing (2001) o Maniac Summer (2009) funzionano come stanze psichiche. Non si tratta di assistere, ma di entrare.

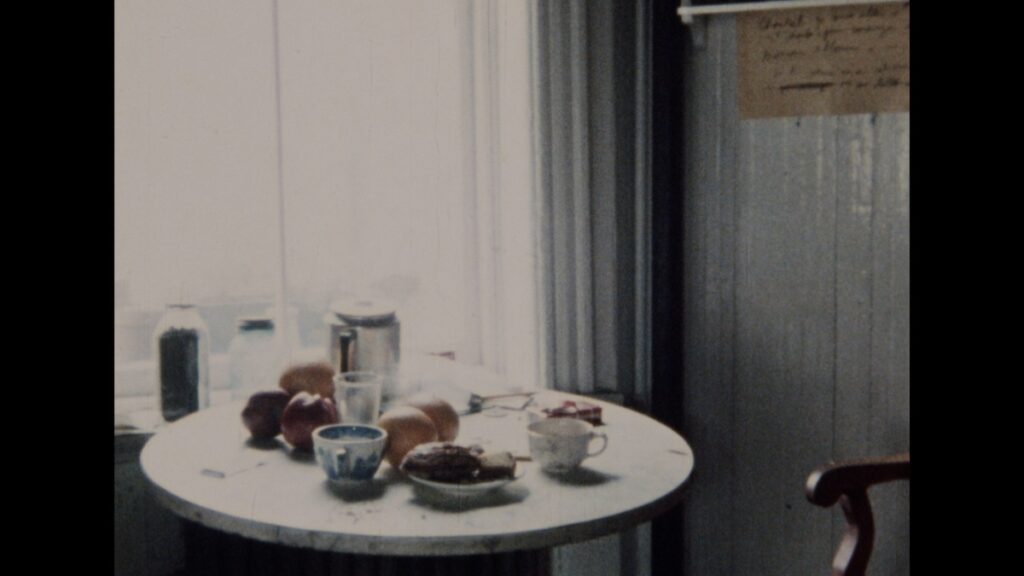

Maniac Summer, o l’estate come sospensione paranoica, è una delle opere più enigmatiche e disturbanti di Chantal Akerman. Realizzata nel 2009, l’installazione si compone di tre proiezioni video simultanee che testimoniano una stagione senza eventi, eppure carica di un’inquietudine sorda, quasi claustrofobica. Akerman riprende se stessa nel proprio appartamento di Parigi, durante un’estate trascorsa da sola, attraversata da un’angoscia latente e diffusa — una “maniacal summer” come lo definisce lei stessa, in cui il tempo sembra addensarsi anziché passare.

Nelle immagini, frammenti di routine: tende che si muovono lievemente, stanze vuote, la cineasta che scrive, cammina, fuma, parla al telefono, si osserva. Ma nulla accade davvero. Non c’è progressione, né climax. C’è solo la registrazione quasi ossessiva del presente, della stasi, del gesto minimo ripetuto — che è uno dei fondamenti estetici dell’intero lavoro di Akerman.

“I was filming so as not to fall into total madness”, scriveva nei suoi appunti. Maniac Summer è, allora, un diario visivo della sorveglianza interiore. Non una narrazione, ma un campo di tensione tra presenza e disintegrazione. È come se il dispositivo filmico servisse ad arginare l’angoscia, a contenerla in una forma, a impedirle di deflagrare.

La casa, come in Saute ma ville o Jeanne Dielman, ritorna come spazio semiotico fondamentale: non più teatro di azioni, ma luogo che filtra il tempo attraverso i dettagli — una finestra socchiusa, il fruscio dell’aria, lo scricchiolio di un parquet. L’immagine di Akerman, solitaria e immersa nella penombra, è quella di una figura liminare: non un personaggio, ma un corpo che registra il proprio sprofondamento.

In mostra, l’installazione funziona come interruzione e snodo. Dopo i lavori sulla diaspora e la memoria storica (D’Est, Là-bas), Maniac Summer riporta tutto nell’interiorità, in un’autobiografia radicale che non racconta, ma esibisce il tempo stesso dell’angoscia. È uno dei lavori più spogli e più intimi, e proprio per questo tra i più difficili da attraversare. Non ci guida alcuna voce fuori campo, nessuna struttura narrativa: solo la durata, la ripetizione, l’ossessione.

E forse è proprio questa l’eredità più vertiginosa di Maniac Summer: aver saputo trasformare la solitudine in forma, il disagio in ritmo, il tempo vissuto in superficie che ci guarda, che ci include.

In NOW (2015), pensata poco prima della morte dell’artista, sei proiezioni simultanee in uno spazio chiuso alternano suoni, immagini e buio con violenza. Il CCB diventa qui cassa di risonanza dell’angoscia contemporanea: la sua sobrietà costruttiva, fatta di pietra chiara e volumi spogli, si presta perfettamente all’implosione sonora dell’opera.

Un’angoscia che risuona anche nel corpo storico del Portogallo, paese attraversato da un lungo regime autoritario (l’Estado Novo), segnato da silenzi imposti, sorveglianza e diaspora. La tensione tra visibile e invisibile, tra parola e rimozione, che percorre l’opera di Akerman, trova qui un terreno silenziosamente affine.

Il montaggio curatoriale di Laurence Rassel rinuncia alla didascalia per lasciare parlare le opere tra loro, come nei diari filmati dell’artista, dove ogni immagine è anche risposta a un’altra. L’ultima sala, dedicata alla madre Natalia, è una chiusura senza fine: una camera di risonanza emotiva.

Che cosa significa oggi, nel 2025, ripercorrere l’opera di Chantal Akerman in un contesto europeo segnato da nuove forme di esilio, sorveglianza e solitudine? La mostra di Lisbona risponde non con tesi, ma con presenze. Il film No Home Movie (2015), testamento artistico e personale dell’autrice, diventa qui emblema della crisi dell’appartenenza. La casa non è mai stata solo un luogo fisico per Akerman, ma un fragile punto di contatto tra intimità e storia, tra la soggettività e il vuoto lasciato dalla Shoah, dalla migrazione, dalla scomparsa della madre.

In un’epoca in cui tutto tende all’accelerazione e all’iper-esposizione, l’opera di Akerman rimane radicale proprio perché insiste sul dettaglio, sull’ellisse, sul non detto. In questo senso, Travelling è una mostra necessaria, non celebrativa, ma quasi terapeutica: costringe a rallentare, a guardare di nuovo, a stare.

La sezione dedicata agli archivi personali rappresenta uno dei nuclei più intensi e rivelatori del percorso espositivo. Non si tratta semplicemente di documenti di accompagnamento o materiali di contesto, ma di una vera e propria zona liminale in cui l’opera e la vita, la scrittura e l’immagine, l’intimità e la riflessione pubblica si intrecciano. Si ha accesso a lettere, appunti manoscritti, annotazioni di regia, fotografie, oggetti, documenti di viaggio e frammenti, diari. I materiali non sono esposti in maniera filologica o celebrativa, ma dispiegati in modo da far emergere il carattere processuale e incompiuto dell’opera di Akerman. Un’opera in costante riscrittura, fragile e potente, attraversata da una tensione irriducibile tra rigore formale e vulnerabilità emotiva.

L’archivio, allora, non è un deposito, ma un’estensione del corpo e della mente dell’artista. Non espone semplicemente le radici del lavoro, ma ne mostra le ferite e i fantasmi. La presenza ricorrente della madre, figura assiale in molte sue opere si ritrova anche in queste carte: lettere spedite e mai ricevute, scritte in francese, in yiddish, in quel tono sospeso tra l’affetto e la distanza che è anche la grammatica dell’esilio. Questa parte della mostra dialoga direttamente con l’idea di archivio intesa non solo come conservazione, ma come dispositivo critico, nella linea tracciata da teoretici come Jacques Derrida in Mal d’archive o Giorgio Agamben. Molto significativo è anche il modo in cui questa sezione è allestita, con un gesto quasi devoto, che rimanda al tempo della lettura privata, al ritmo interiore del pensiero. Si impone come un atto d’amore verso la memoria, non nel senso nostalgico o familiare, ma come esercizio politico e formale.

“Mon travail est une lutte contre l’effacement.”

In questa lotta, l’archivio non salva solo il passato. Tiene aperta la possibilità di una sopravvivenza. Di una presenza che continua a parlare, anche dopo il silenzio. Come scrive Arlette Farge in Le goût de l’archive, «l’archivio è il luogo di un’intimità senza volto, in cui il frammento contiene più verità della narrazione coesa». Questo vale radicalmente per l’archivio Akermaniano: ogni frammento, ogni nota, ogni foglio ripiegato e riscritto più volte non conferma, ma incrina l’identità dell’autrice. La attraversa. Come se in ogni appunto ci fosse non tanto un pensiero, quanto un’interferenza emotiva, un’oscillazione della memoria.

L’archivio non è mai solo autoriale, ma collettivo, genealogico, affettivo. Un “archivio d’amore”, come avrebbe detto Didi-Huberman, in cui la sopravvivenza passa attraverso immagini fragili, interrotte, prossime alla scomparsa. E tuttavia, ostinatamente presenti.

Con la tappa di Lisbona, la mostra Chantal Akerman. Travelling non si limita a proseguire un itinerario espositivo: lo trasforma. Da retrospettiva a esperienza estetica, da archivio a paesaggio.E lo fa nel cuore di un paese come il Portogallo, che conosce il peso delle partenze, dei ritorni mancati, della distanza come forma di sopravvivenza. La storia coloniale, le migrazioni post-imperiali, la memoria ancora aperta della dittatura e la fragile transizione democratica fanno di Lisbona un luogo in cui il tempo non guarisce, ma sedimenta. In un’epoca votata alla spettacolarizzazione, Travelling si fa epifania del minimo, geografia del fragile, topologia dell’inapparente e in questa metamorfosi, l’opera di Akerman si rivela per ciò che è sempre stata: una pratica di resistenza, fragile e ostinata, al tempo lineare, alla narrazione univoca, all’oblio.

“Je fais du cinéma avec mon corps, mes obsessions, mes peurs, ma mémoire.” (Chantal Akerman)

Topographies of Affection. The Final Stage of Chantal Akerman. Travelling

Text by Rita Selvaggio —

With the exhibition Chantal Akerman. Travelling, the Museu de Arte Contemporânea at the Centro Cultural de Belém hosts the third—and most atmospheric—chapter of a curatorial journey that began in Brussels and continued in Paris. In each venue, Akerman’s work has encountered a different architectural and affective resonance, adapting to the rhythms and voids of the spaces, just as her films accommodate the slowness of static shots and the geometry of everyday gestures.

The MAC/CCB is far from a neutral space: designed by Vittorio Gregotti and Manuel Salgado, the building unfolds as a sequence of interior piazzas, open areas, and corridors that give onto courtyards and apertures of light. Constructed from pale stone and modular volumes, the architecture incorporates the temporality of the gaze: it is a space that demands slowness, that must be traversed. Unlike the previous venues—marked by historiographical rigour in Brussels and thematic emphasis in Paris—the Lisbon exhibition finds a sensory counterpoint in the architecture itself. Here, the spaces do not confine the installations within museal frames, but allow them to breathe. The result is a form of exhibition-making that seems to replicate the grammar of Akerman’s cinema: pauses, interstices, silences that become active. The visitor is immersed in a perceptual dimension in which time does not progress but expands—does not flow but suspends, dilates.

It is Lisbon itself—with its oblique light and marginal architecture—that offers an ideal counterpoint to Akerman’s work. A city of departures and returns, of colonial transits and Atlantic melancholies, Lisbon bears a historical stratification in which themes of mourning, absence, and exile find deep resonance. It is as if the urban landscape—suspended between ruins and promises—amplifies the temporal and affective dimension of the works on display.

In Brussels (Bozar), the exhibition unfolded as a homecoming: a museum of memory shaped by the chronological clarity of a critical archive. In Paris (Jeu de Paume), it highlighted connections with the feminist avant-garde, the Jewish diaspora, and American experimental cinema. In Lisbon, the installation enters into dialogue with the open architecture of the MAC/CCB: the exhibition becomes an experiential space, where the “travelling” of the title emerges as an existential stance.

Here, the work detaches itself from biographical time and becomes substance—a slow montage of absences—and Akerman, who always filmed borders, reveals herself as a cartographer of the threshold.

The exhibition opens with Saute ma ville (1968), a foundational work and, at the same time, a symbolic detonator for the entire Akermanian constellation. It is not merely a debut: it is a threshold, an explosive prologue that announces—in germinal yet already radical form—the visual and conceptual language that will permeate all of her later work. Shot at just eighteen, the film is a poetic and premonitory short circuit. A rupture—in the most literal and symbolic sense. It lasts just over ten minutes but already contains, in embryonic and violent form, many of the obsessions that will haunt Akerman’s oeuvre: the confined female body, the home as a claustrophobic space, the repetition of gestures, the implosion of time, the unsettling relationship with the mother, the scream that is silence.

Akerman is both in front of and behind the camera. She enters an apartment, seals the windows, turns on the gas, hums, puts on makeup, cleans, violently assaults everyday objects. In a surreal crescendo, the kitchen—the domestic and quintessentially feminine space—becomes the stage for a slow, inexorable combustion. In the end, the explosion. Offscreen.

The film ends in black, like an omen. And today, it is impossible not to read it also as a tragic intuition, an unsettling prophecy. Saute ma ville is not merely a proto-feminist gesture, nor simply an existential performance: it is a declaration of poetics enacted through the body.

Akerman stages, with atrocious and childlike irony, the paradox of a subject attempting to escape the order—domestic, narrative, symbolic—that oppresses her. But the escape is never complete. The extreme act, the destruction, becomes a way to inhabit space. To leave a trace. A void.

As the artist herself would write, years later:

“My work is nothing but a long love story with my mother, and with mothers.”

And perhaps Saute ma ville is the first chapter of that silent novel: a cry that pierces the walls of the home, an act of love and violence at once, the foundation of a visual language that from the very beginning rejects ornament, illusion, narration.

It is a cinema that explodes—and in its detonation, it begins.

One of the strengths of this Lisbon exhibition lies in its recognition that Akerman’s work is not merely cinema, but a way of inhabiting: inhabiting time, inhabiting trauma, inhabiting language. In this sense, video installations such as Woman Sitting After a Killing (2001) or Maniac Summer (2009) function as psychic rooms. These are not works to be merely observed — they are spaces to enter.

Maniac Summer, or summer as a paranoid suspension, is one of Akerman’s most enigmatic and unsettling works. Created in 2009, the installation consists of three simultaneous video projections, bearing witness to a season without events, yet charged with a muted, almost claustrophobic unease. Akerman films herself in her Paris apartment during a summer spent alone, haunted by a pervasive, latent anguish — a “maniacal summer,” as she herself called it, in which time seems not to pass but to congeal.

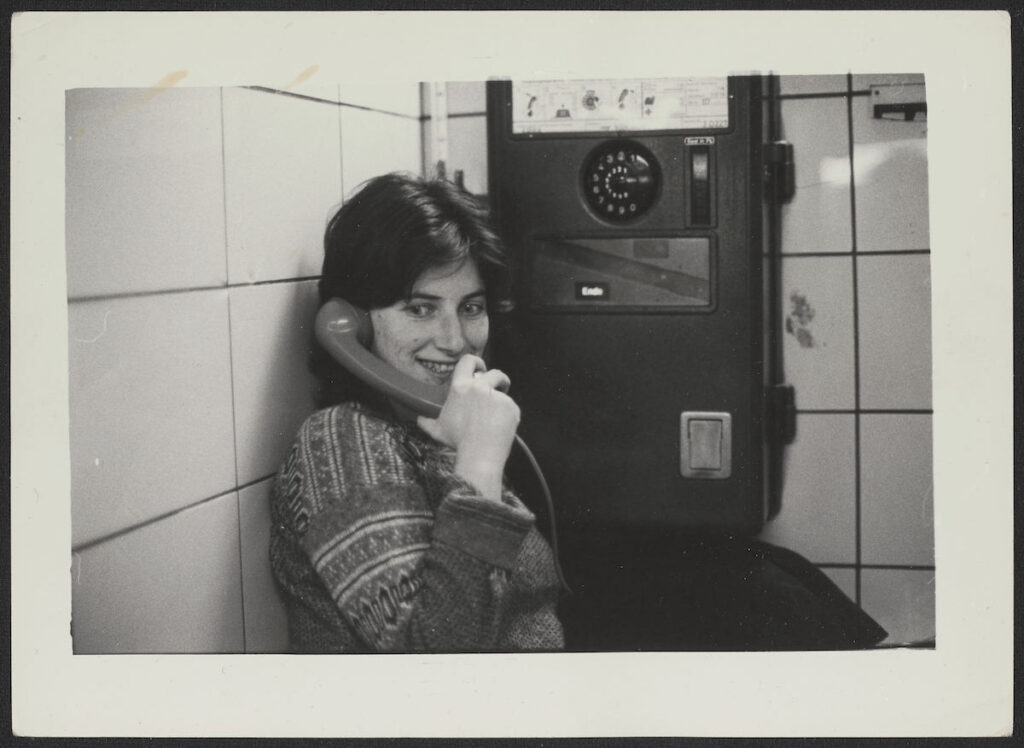

What the images reveal are fragments of routine: curtains swaying gently, empty rooms, the filmmaker writing, walking, smoking, talking on the phone, watching herself. And yet nothing truly happens. There is no progression, no climax. Only the near-obsessive recording of the present, of stasis, of the repeated minimal gesture — one of the aesthetic foundations of Akerman’s entire body of work.

“I was filming so as not to fall into total madness,” she wrote in her notes. Maniac Summer is thus a visual diary of inner surveillance. Not a narrative, but a field of tension between presence and disintegration. It is as if the filmic apparatus served to contain anxiety, to hold it within a form, to keep it from erupting.

As in Saute ma ville or Jeanne Dielman, the house reappears as a fundamental semiotic space: no longer a stage for actions, but a filter through which time passes in fragments — a half-open window, the rustle of air, the creak of a floorboard. The image of Akerman, solitary and immersed in shadow, is that of a liminal figure: not a character, but a body registering its own descent.

In the exhibition, the installation functions as both rupture and hinge. After her works on diaspora and historical memory (D’Est, Là-bas), Maniac Summer brings everything back into the interior, into a radical autobiography that does not narrate, but instead exposes the very time of anguish. It is one of Akerman’s barest and most intimate works—and precisely for this reason, among the most difficult to endure. There is no guiding voiceover, no narrative structure: only duration, repetition, obsession.

And perhaps this is Maniac Summer’s most vertiginous legacy: the ability to transform solitude into form, discomfort into rhythm, lived time into a surface that looks back at us, that includes us.

In NOW (2015), conceived shortly before the artist’s death, six simultaneous projections in a closed space alternate sound, image, and darkness with violence. At the CCB, the installation becomes a resonating chamber for contemporary anguish: its austere architecture, made of pale stone and stripped-down volumes, lends itself perfectly to the work’s sonic implosion.

A form of anguish that also echoes in the historical body of Portugal, a country marked by a long authoritarian regime (Estado Novo), shaped by imposed silences, surveillance, and diaspora. The tension between the visible and the invisible, between speech and erasure, which runs throughout Akerman’s oeuvre, finds here a quietly kindred ground.

The curatorial montage by Laurence Rassel does away with captions to let the works speak to each other, as in the artist’s filmed diaries, where every image is also a response to another. The final room, dedicated to her mother Natalia, is a closure without end: a chamber of emotional resonance.

What does it mean today, in 2025, to retrace the work of Chantal Akerman in a European context marked by new forms of exile, surveillance, and solitude? The Lisbon exhibition responds not with theses, but with presences. The film No Home Movie (2015), the author’s artistic and personal testament, becomes here an emblem of the crisis of belonging. Home was never merely a physical place for Akerman, but a fragile point of contact between intimacy and history, between subjectivity and the void left by the Shoah, by migration, by the disappearance of the mother.

In an age dominated by acceleration and overexposure, Akerman’s work remains radical precisely because it insists on the detail, on ellipsis, on the unspoken. In this sense, Travelling is a necessary exhibition — not celebratory, but almost therapeutic: it forces us to slow down, to look again, to remain.

The section devoted to personal archives represents one of the most intense and revealing cores of the exhibition. These are not simply accompanying documents or contextual materials, but a true liminal zone where work and life, writing and image, intimacy and public reflection intertwine. Visitors are granted access to letters, handwritten notes, director’s annotations, photographs, objects, travel documents and fragments, diaries. The materials are not exhibited in a philological or celebratory manner, but laid out in such a way as to highlight the processual and unfinished nature of Akerman’s work. A body of work in constant rewriting, fragile and powerful, traversed by an irreducible tension between formal rigour and emotional vulnerability.

The archive, then, is not a repository, but an extension of the artist’s body and mind. It does not simply expose the roots of the work, but reveals its wounds and ghosts. The recurring presence of the mother — a pivotal figure in many of her works — resurfaces in these papers too: letters sent and never received, written in French, in Yiddish, in that tone suspended between affection and distance that is also the grammar of exile.

This part of the exhibition directly engages with the idea of the archive not only as preservation, but as a critical device, in the lineage traced by theorists like Jacques Derrida in Mal d’archive or Giorgio Agamben. Particularly significant is the way this section is installed — with an almost devotional gesture, recalling the time of private reading, the inner rhythm of thought. It asserts itself as an act of love toward memory — not in a nostalgic or familial sense, but as a political and formal exercise.

“Mon travail est une lutte contre l’effacement.”

In this struggle, the archive does not merely preserve the past. It keeps open the possibility of survival—of a presence that continues to speak, even after silence. As Arlette Farge writes in Le goût de l’archive, “the archive is the place of a faceless intimacy, where the fragment contains more truth than the cohesive narrative.” This applies profoundly to the Akermanian archive: each fragment, each note, each sheet folded and rewritten multiple times does not affirm but rather fractures the identity of the author. It traverses her. As if in every jotting there were not so much a thought as an emotional interference, a tremor of memory.

The archive is never merely authorial—it is collective, genealogical, affective. An “archive of love,” as Didi-Huberman might say, where survival passes through fragile, interrupted images, on the verge of disappearance. And yet, stubbornly present.

With the Lisbon stage, Chantal Akerman. Travelling does not merely continue an exhibition itinerary—it transforms it. From retrospective to aesthetic experience, from archive to landscape. And it does so in the heart of a country like Portugal, a land marked by departures, by returns that never happened, by distance as a form of survival. Colonial history, post-imperial migrations, the still-open wound of dictatorship, and the fragile democratic transition make Lisbon a place where time does not heal but settles in layers. In an age obsessed with spectacle, Travelling becomes an epiphany of the minimal, a geography of the fragile, a topography of the unapparent. And in this metamorphosis, Akerman’s work reveals itself for what it has always been: a fragile yet stubborn practice of resistance—against linear time, against singular narratives, against oblivion.

“Je fais du cinéma avec mon corps, mes obsessions, mes peurs, ma mémoire.” (Chantal Akerman)

Temporary exhibition until September 7th 2025