English text below —

PERMANENT TRESPASS

(BEIRUT OF THE BALKANS

& THE AMERICAN CENTURY)

Sceneggiatura per Live Works 11 di Centrale Fies

Spettacolo messo in scena il 1. Luglio 2023

di Sanja Grozdanić & Bassem Saad

Gli Elogisti Parlano di Lavoro / Lutto Professionale

[L’ELOGISTA 1 e l’ELOGISTA 2 sono seduti su un divano bianco, scomodamente vicini. I due iniziano a parlare di lavoro: sono elogisti itineranti che condividono ispirazioni e risentimenti professionali].

ELOGISTA 1: Qui c’è scritto: “Fuori tutto”. Ogni singolo divano, poltrona, pianoforte, manifesto, ogni pamphlet, opuscolo, libretto, novella e operetta trasportati dall’aria. È una sorta di… vendita in saldo del linguaggio stesso… ma non lo so, o non ne sono sicuro; sono ancora in preda al jet lag. Anche tu sei qui per la cerimonia?

ELOGISTA 2:Sì, sono l’elogista itinerante. Non mi hanno detto che era anche una vendita immobiliare. Se lo avessi saputo, non sarei mai venuto. Sono molto superstizioso, e certi tipi di morte sono contagiosi—

ELOGISTA 1: Attenzione al contratto opaco. L’ho imparato molto tempo fa, eppure eccomi qui. [pausa] Mi affascina il fatto che tu conservi dei tabù — il cinismo è il vero rischio professionale nel nostro lavoro. Com’era la tua stanza d’albergo?

ELOGISTA 2:Terribile. Sono sempre terribili! Una fila di città di provincia con a malapena un hotel tra l’una e l’altra. Dio non voglia che qualcuno muoia vicino a un Hilton. In presenza della morte si immaginano dignità e buone maniere: fiori senza profumo ed espressioni sofferenti, clima mite, spessi tovaglioli di lino. Invece c’è appena il tempo di chiudere l’occhio del cadavere — che arrivano i banditori d’asta e gli avvocati!

ELOGISTA 1:Avresti dovuto fare il banditore d’asta, almeno è pagato meglio.

ELOGISTA 2:È troppo tardi per cambiare formazione. E le illusioni che ci vengono commissionate sono relativamente benigne, moralmente insignificanti. Cioè, posso conviverci. Anzi, posso trovare una scusa per questo! “Quale bisogno umano può essere più profondo che umanizzare la morte comune?”. [Si alza] Hai visto questo film, Sindrome Astenica? Lo guardo prima di ogni servizio funebre, perché comincia proprio con un funerale. La donna in lutto, il cui marito defunto assomiglia decisamente a Stalin, viene prima infastidita da due uomini con cui poi si infuria e che sembrano chiacchierare del più e del meno. Riecheggiano risate e riverberano disprezzo e indifferenza.

ELOGISTA 1:Ma il dolore ci rende instabili, testimoni inaffidabili. Ho sentito parecchie storie di gente che ha riso ai funerali, anche chi è più intimamente in lutto — e se chi rideva fosse stato davvero triste?

ELOGISTA 2:No, quelle persone erano insolenti. Non si può buttare un corpo sotto terra e basta; ci sono codici e cerimonie ed è ciò che siamo qui a fare! Comunque. Era il 1989. Il “ventesimo secolo breve” era finito. Il problema era come contenere la perdita. E la nostra domanda?

ELOGISTA 1:Tutto è sempre in via di definizione in questo momento stesso; sembra un ribollire che non arriverà mai a ebollizione. Mi ritrovo a desiderare che finalmente bolla.

ELOGISTA 2: Basta catastrofismo! Devi usare al meglio il minibar.

ELOGISTA 1: Oh, il minibar. Un’altra vittima della nostra epoca. Mi hanno messo in un Airbnb. Non ti sembra che tutto sia stato declassato? [pausa, spostamenti sul palco]

Che cosa dice il fatto che i tuoi appunti preparatori sono cinema oscuro? Torno sempre a The Arab Dream (Il Sogno Arabo) — intendo l’operetta, non il sogno pan-nazionalista in sé. L’operetta era fondamentalmente un lungo video musicale con le più grandi pop star arabe dell’epoca, trasmesso in TV in tutto il mondo arabo durante la Seconda Intifada palestinese. Conteneva orribili filmati d’archivio, a partire dalla prima espulsione dei palestinesi fino all’ascesa e alla caduta di Jamal Abdel Nasser, con tanto di pianto di donne dopo ogni massacro.

Non è chiaro per cosa si fosse in lutto: la perdita dell’unità araba, la perdita di una patria palestinese o, ancora di più, la perdita del padre panarabista, chissà. Le donne che piangevano erano state messe al servizio di questo lutto mal definito.

ELOGISTA 2: Dare un significato a qualcosa che non ha senso è un tradimento o un’arte, o semplicemente la vita stessa. In un elogio professionale, si porta ancora una volta la morte sul mercato; si crea un’ulteriore traccia cartacea per quella vita. In un’aula di tribunale, in un processo per omicidio…

ELOGISTA 1: Stai esagerando.

ELOGISTA 2: Scusa! Nel tentativo di calpestare i miei stessi piedi, finisco per inciampare e cadere.

ELOGISTA 1: Sì, è così. Ma continua.

ELOGISTA 2: In un’aula di tribunale, in un processo per omicidio, si restituiscono le morti alla legge; si dice che non appartengono alla sala delle contrattazioni. Ma il loro posto è proprio nella sala delle contrattazioni. È una questione di onestà.

ELOGISTA 1: [beffardamente] Oh, onestà?

ELOGISTA 2: Sì, onestà!

ELOGISTA 1: Suppongo di sì. Raramente sono “onesto”, quando parlo dei morti, ma lo sono, quando chiedo il mio compenso.

ELOGISTA 2: Ok, ok, ho capito: noi, i volgari materialisti. Ora! Questa è più una questione di prassi professionale, quasi un tecnicismo: nei tuoi discorsi riporti ancora le date?

ELOGISTA 1: Le date?

ELOGISTA 2: Le date: gli anni simbolo, le tappe fondamentali…

ELOGISTA 1: [con sicurezza, bruscamente]Oh, ho smesso.

ELOGISTA 2:[vigorosamente d’accordo, scuotendo la testa]. Anch’io ho smesso. La qualità della ricerca diventa piuttosto noiosa dopo un po’: 1945 questo, 1948 quello, 1968 quello, 1967 quello, 2023… questo.

ELOGISTA 1: Ho sempre preferito una narrazione più strettamente virtuosistica. Causa ed effetto sono — per definizione — consequenziali, ma è proprio necessario sapere quando il marito di qualcuno è stato riscattato, quando l’alluvione ha portato via tutto, quando Yasser Arafat ha avuto il suo primo e unico figlio?

***

BREVE NOTA SULLA SCENEGGIATURA E SUL PROCESSO

Nel 2021, quando abbiamo realizzato la prima iterazione di Permanent Trespass, pensavamo all’apocalisse come genere letterario. All’alba di una nuova apocalisse, era ancora plausibile presentare varie forme di nichilismo come critica. La lettura di testi come The Sense of an Ending di Frank Kermode ci ha ricordato di collocare queste opere all’interno della loro tradizione (escatologica cristiana), mentre altri scrittori contemporanei (Dubravka Ugrešić, Walid Sadek) ci hanno interrogato sulla possibilità e sulla mutevolezza del lutto attraverso la morte prolungata e ripetuta.

Alla fine alcuni di questi quadri di riferimento ci hanno portato ai due ruoli più discreti delineati nella sceneggiatura precedente. Come suggerisce il titolo dell’opera, ci stiamo ancora chiedendo se c’è un corpo da seppellire (viviamo ancora in un secolo “americano”? Quali tipi di microstorie o narrazioni lo sostengono o lo rifiutano?), ma siamo anche interessati ad affrontare il tipo di doppia esposizione di passato e presente che si verifica in questi momenti di transizione storica. L’elogista professionista è una sorta di mercante di morte—un consulente, un broker assicurativo—un sommo sacerdote o un altro precario all’interno del nostro ordine simbolico? Abbiamo cercato di creare un set anti-superficie per mostrare questa crepa o condizione: una sorta di modernismo IKEA che costringe i due personaggi a essere completamente estranei all’ambiente circostante (qui le idee di Brecht sono pertinenti). Per citare le prime battute dello spettacolo—fuori tutto.

L’estratto qui sopra è tratto dal libro di Susan Buck-Morss Dreamworld and Catastrophe: The Passing of Mass Utopia in East and West, un altro riferimento del nostro processo di scrittura iterativa. Una breve cronologia del “Tempo Mitico” nel libro inizia con la morte di Lenin nel 1924 (“Alzatevi, compagni, Illich viene calato nella tomba!”) e termina nel 1997, con le richieste di mandare il suo corpo imbalsamato (che, secondo gli scienziati coinvolti nel processo, “dovrebbe durare per sempre” e costare solo 7500 dollari—progresso!) in un tour mondiale. L’inizio e la fine non sono sempre visibili. A volte sono evidenti. Qui Lauren Berlant: “Di solito la speranza è che la commedia ripari l’infelicità. Nella commedia priva di umorismo, “da dove viene la comicità?” e “da dove viene l’infelicità?” sono la stessa domanda: una domanda che riguarda l’umorismo, senza alcuna riparazione in vista.”

Bassem Saad è un artista e scrittore di Beirut. Il suo lavoro sonda le nozioni di rottura storica, spontaneità e surplus attraverso cinema, arti performative e scultura, oltre che saggi e fiction. Con un’enfasi su tensioni come quella tra passato e presente, tenta di creare scene di scambio intersoggettivo all’interno delle proprie cornici storico-mondane.

Sanja Grozdanić è una scrittrice residente a Berlino. La sua scrittura si concentra in particolare su questioni legate alla memoria, all’espropriazione, alla devianza e agli slittamenti tra dolore pubblico e privato, ansia e immaginazione.

Permanent Trespass (Beirut of the Balkans and the American Century / La Beirut dei Balcani e il Secolo americano) è una performance basata su un copione di Sanja Grozdanic e Bassem Saad. Scavando nelle storie nazionali, gli artisti chiamano in causa diverse parti, tra cui gli aggressori suprematisti, le loro vittime, la Corte penale internazionale. Ciò che è continuamente rinviato è la rivoluzione.

La performance, che descrive la documentazione storica come “insidiosamente incompleta”, mette in discussione le rappresentazioni della guerra e della giustizia da diversi punti di vista. Nella cornice dell’allarmante decadenza e del declino estremo di un presente inaugurale: freddi tropi, metaforici ordigni di guerra, disperati giochi di parole.

PERMANENT TRESPASS

(BEIRUT OF THE BALKANS

& THE AMERICAN CENTURY)

Script for centrale fies’s Live Works 11

Performed on July 1st 2023

by Sanja Grozdanić & Bassem Saad

Eulogists Talk Shop / Professional Mourning

[EULOGIST 1 and EULOGIST 2 sit on a white couch, uncomfortably close. The two begin “talking shop:” they are traveling eulogists sharing occupational inspirations and resentments.]

EULOGIST 1: It says here that everything must go! Every single sofa, armchair, piano, manifesto, every airborne pamphlet, leaflet, booklet, novella, and operetta. It’s a kind of …clearance sale on language itself… but I don’t know, or I’m not sure; I am still jet lagged. You’re here for the ceremony too?

EULOGIST 2: Yes, I’m the traveling eulogist. They didn’t tell me it was also an estate sale. Had I known, I would never have come. I’m very superstitious, and certain kinds of death are contagious—

EULOGIST 1: Beware the opaque contract. I learned that a long time ago, yet here I am. [pause] I’m charmed that you retain taboos — cynicism is the real occupational hazard in our line of work. How was your hotel room?

EULOGIST 2: Terrible. They always are! It’s one provincial town after the other, barely a hotel between them. God forbid someone dies in proximity to a Hilton. In the presence of death, one imagines dignity and manners: scentless flowers and sorrowful expressions, temperate weather, thick linen napkins. Instead, there is barely time to shut the eye of the cadaver —in come the auctioneers and lawyers!

EULOGIST 1: You would’ve been better off an auctioneer, I mean at least better compensated.

EULOGIST 2: Too late to retrain. And the illusions we’re commissioned for are comparatively benign, morally insignificant. What I mean is, I can live with it. In fact, I can pitch an excuse for it! “What human need can be more profound than to humanize the common death?” [gets up] Have you seen this film, Asthenic Syndrome? I watch it before every funeral since it opens with one. The woman who is grieving—whose deceased husband bears more than a passing resemblance to Stalin—is disturbed and then infuriated by two men who appear to be having a casual conversation. Laughter echoes and reverberates contempt and indifference.

EULOGIST 1: But grief makes us unstable, unreliable witnesses. I’ve heard numerous stories of laughter at funerals, even by the most intimately bereaved—what if the laughing men were indeed morose?

EULOGIST 2: No, the men were insolent. You can’t just throw a body into the earth; there are codes and ceremonies, and that is what we’re here to practice! Anyway. It was 1989. The “short-twentieth century” was over. The question was how to contain loss-ness. And our question?

EULOGIST 1: Everything is always being settled at this very moment; it feels like a simmering that will never boil over. I find myself wishing that it would finally boil over.

EULOGIST 2: Enough catastrophism! You have to make the best use of the minibar.

EULOGIST 1: Oh, the minibar. Another casualty of our era. They’ve put me in an Airbnb. Does it feel like everything has been downgraded? [pause, shuffling around the stage]

What does it say that your preparatory notes are obscure cinema? I always return to The Arab Dream—I mean the operetta, not the pan-nationalist dream itself. The operetta was basically a long music video with the biggest Arab pop stars of the time that played on TV across the Arab world during the Second Palestinian Intifada. It contained horrific archival footage, starting with the first Palestinian expulsion through the rise and fall of Jamal Abdel Nasser, complete with wailing women after every massacre.

What was being mourned remains unclear: the loss of Arab unity, the loss of a Palestinian home, or, more so, the loss of the pan-Arabist father who knows. The wailing women were put in the service of this ill-defined mourning.

EULOGIST 2: Making meaning out of something that makes no sense is betrayal or an art, or simply life itself. In a professional eulogy, you bring death once again to the market; you make one more paper trail for that life. In a courtroom, in a murder trial…

EULOGIST 1: You’re getting ahead of yourself.

EULOGIST 2: Sorry! In my attempt at stepping over my own feet, I end up tripping and falling.

EULOGIST 1: Yes, you do. But go on.

EULOGIST 2: In a courtroom, in a murder trial, you return the deaths to the law; you say they don’t belong on the trading room floor. But they do belong on the trading room floor. It’s a question of honesty.

EULOGIST 1: [mockingly] Oh, honesty?

EULOGIST 2: Yes, honesty!

EULOGIST 1: I suppose. I am rarely “honest” when speaking of the dead, but I am honest when asking for my salary.

EULOGIST 2: Okay, okay, I get it: us, the vulgar materialists. Now! This is more a question of professional practice, almost a technicality: in your speeches, do you still include the dates?

EULOGIST 1: The dates?

EULOGIST 2: The dates. Like the landmark years, milestones, …

EULOGIST 1: [assuredly, abruptly] Oh, I’ve stopped.

EULOGIST 2: [in vigorous agreement, shaking head] I’ve stopped as well. The searching quality gets so tedious after a certain point: 1945 this, 1948 that, 1968 that, 1967 that, 2023… this.

EULOGIST 1: I’ve always preferred a more strictly virtuosic narration. Cause and effect are—by definition—consequential, but do you absolutely have to know when someone’s husband was ransomed off, when the flood took everything, when Yasser Arafat had his firstborn and only child?

***

SHORT NOTE ON SCRIPT AND PROCESS

In 2021, when we performed the first iteration of Permanent Trespass, we were thinking about apocalypse as a literary genre. As a new apocalypse dawned, it was still plausible to present various forms of nihilism as critique. Reading texts such as Frank Kermode’s The Sense of an Ending reminded us to locate such fictions within their (Christian eschatological) tradition, while other contemporary writers (Dubravka Ugrešić, Walid Sadek) asked us about the possibility and mutability of mourning through protracted and repeated death.

Eventually, some of these frames of reference led us to the two more discrete roles outlined in the script above. As the title of the work implies, we’re still asking whether there is a body to bury (are we still living in an ‘American’ century? What kinds of micro-histories or narratives support or reject that?), but we’re also interested in addressing the kind of double exposure of past and present that occurs at such moments of historic transition. Is a professional eulogist a kind of death dealer—a consultant, an insurance broker—a high priest or another precariat within our symbolic order? We tried to create an anti-surface set to show this crack or condition: a kind of IKEA modernism forcing the two characters to be fully estranged from their surroundings (Brecht’s ideas are pertinent here). To quote the first lines of the performance here—everything must go.

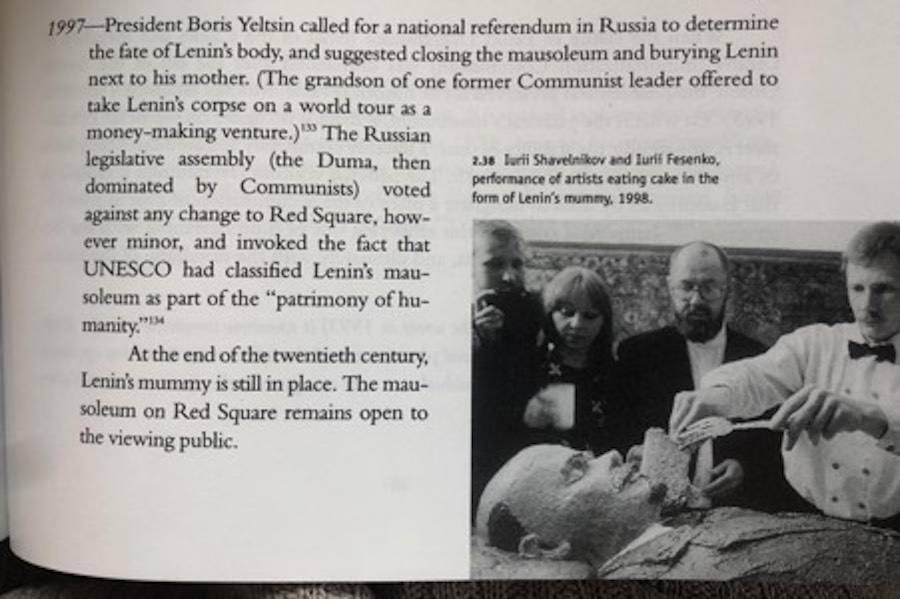

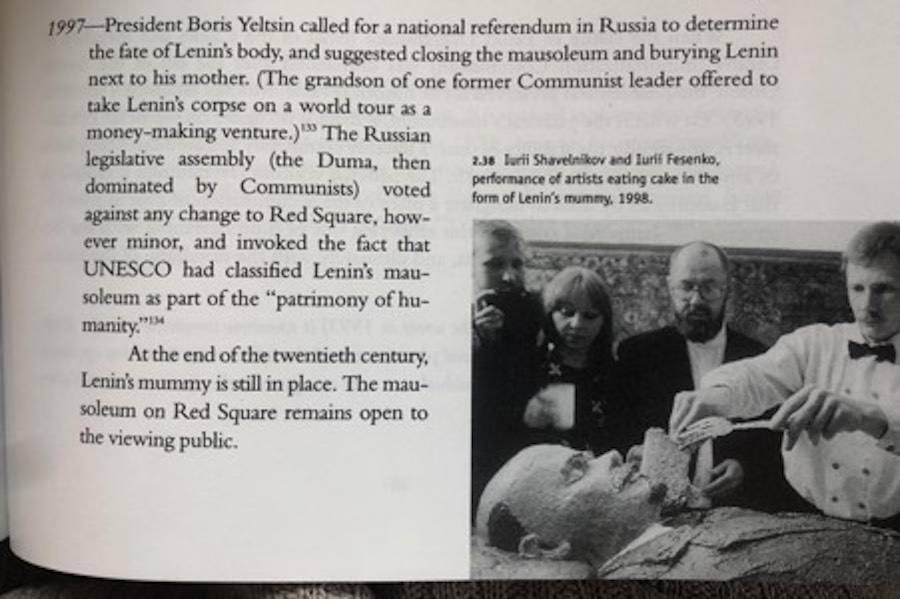

The above clipping is from Susan Buck-Morss’s Dreamworld and Catastrophe: The Passing of Mass Utopia in East and West, another reference from our iterative writing process. A brief chronology of “Mythic Time” in the book begins with Lenin’s death in 1924 (“Stand up, comrades, Illich is being lowered into his grave!”) and ends in 1997, with calls to send his embalmed body (which, according to the scientists involved in the process, “should last forever” and only cost $7500—progress!) on a world tour. Beginnings and endings are not always visible. Sometimes, they’re glaring. Lauren Berlant here: “Typically, the hope is that comedy repairs misery. In humorless comedy “where does the comedy come from?” and “where does the misery come from?” are the same question: a question about being humored, with no repair in sight.”

Bassem Saad is an artist and writer born in Beirut. Their work explores notions of historical rupture, spontaneity, and surplus, through film, performance, and sculpture, alongside essays and fiction. With an emphasis on past and present forms of struggle, they attempt to place scenes of intersubjective exchange within their world-historical frames.

Sanja Grozdanić is a writer living in Berlin. Her writing is particularly concerned with issues of memory, dispossession, and deviance, and the slippages between public and private grief, anxiety and imagination.

In Permanent Trespass (Beirut of the Balkans and the American Century), two traveling eulogists meet on a dire tableau: something like our contemporary moment or crumbling epoch. First-person monologues oscillate between formal registers towards a performance within a performance, that of a commissioned funerary text. Who or what is being mourned against a backdrop of incommensurate cruelty? Fantasized digressions hint at jumps in time toward a revolution forever deferred.