English version below

Intervista di Alessandra Maccari e Elena Coco —

“Porre l’attenzione sul corpo significa rimettere in discussione l’idea di cosa siamo e ripensare alle modalità con cui interagiamo tra noi e con le altre entità viventi e non viventi che affollano il mondo. Significa soprattutto scardinare i rapporti di potere che ci vincolano reciprocamente.” Con queste parole Chiara Enzo (Venezia, 1989) – autrice presente nella 59. Esposizione Internazionale d’Arte di Venezia, Il latte dei sogni curata da Cecilia Alemani – ci introduce ai temi della vulnerabilità, del senso di mancanza e di limitatezza che esplora nella sua pratica artistica. Il seguente dialogo vuole mettere in luce alcuni aspetti del suo lavoro in occasione della prossima apertura della mostra collettiva Small Fixations presso la Fondazione ICA Milano.

ALESSANDRA MACCARI: Partiamo col riflettere sul display che adotti dove spesso troviamo un dialogo visivo tra diverse opere, come nel caso dell’installazione Conversation Piece, una ideale conversazione, appunto, che muta a seconda del progetto di mostra: ci si può trovare davanti a una griglia ordinata, a una nuvola di immagini, a una sfilata di disegni o alla giustapposizione di due dipinti e ci si può perdere nel tentativo di trovare connessioni o di indovinare una sequenzialità. Mi chiedo, dunque, se concepisci i tuoi lavori come pezzi unici, come delle serie o se c’è una continuità che rende indefinibile il significato delle singole opere.

CHIARA ENZO: Il mio intento è sempre stato quello di considerare ogni opera come un mondo a sé. I dipinti devono poter essere autonomi ma sono allo stesso tempo parte di un tutto, ognuno comunica con gli altri, li richiama. Ad accendere questa comunicazione è il senso di mancanza, di limitatezza, che caratterizza ogni lavoro, e richiede un completamento irrealizzabile che non può mai esaudirsi. È lo sguardo incarnato in ogni opera ad essere limitato e a voler esprimere questa limitatezza, questa mancanza di chiarezza nei confronti del mondo. Per me la pratica artistica ha sempre significato misurarmi con il potere. Il potere di comprendere, di arrivare il più lontano possibile con lo sguardo e di avere una visione omnicomprensiva del mondo, di confrontarmi con la materia e piegarla al mio volere. Mi sono poi resa conto che più mi sforzavo e più tutto andava in pezzi. Ho iniziato a guardare a questi frammenti, e a tentare di costruire qualcosa a partire da essi.

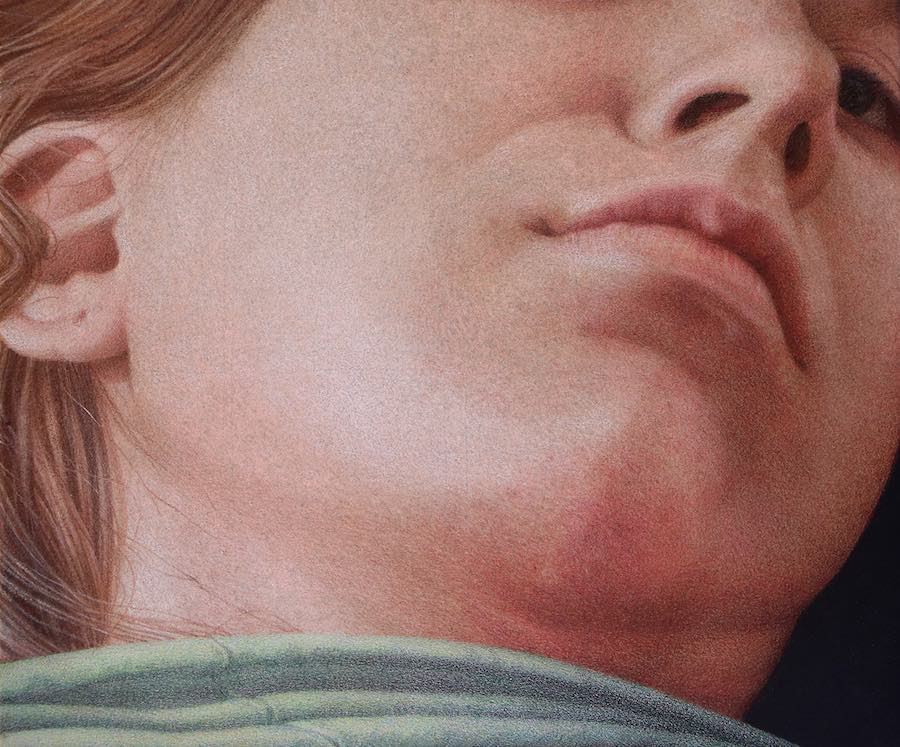

ELENA COCO: Lo sguardo intimo e violento che emerge dalle tue rappresentazioni seduce l’osservatore, andando a creare una relazione di tipo voyeuristico e ambiguo tra il fruitore e i tuoi quadri. In passato, parlando con te, abbiamo notato che spesso l’immagine rappresentata viene percepita come se il tuo occhio l’avesse immortalata con una lente d’ingrandimento, instaurando nell’osservatore la sensazione che si trovi di fronte a dei close-up: quasi a evocare una sorta di effetto perturbante.

CE: Quello che dici è interessante per me, ma è sempre un poco spiazzante ricevere questo responso, perché non ho mai rappresentato figure ingrandite rispetto alla realtà, eccetto un paio di rarissimi casi. Credo che questo effetto si verifichi perché le immagini sono pensate e costruite per tirartici dentro. Lo spostamento fisico messo in atto da chi le guarda fa ripercorrere lo stesso movimento che farebbe, in effetti, uno zoom. L’occhio umano poi arriva fino ad un certo punto, ed è lì che tendo a fermarmi anch’io. Anche l’inquadratura ravvicinata di cui spesso mi servo contribuisce a creare questa illusione. Lo spazio a disposizione è quasi completamente occupato dal soggetto, che quindi in rapporto sembra magnificato.

EC: Un rapido e superficiale approccio alla tua opera può trarre facilmente in inganno per quel che concerne la tecnica. Il procedimento che utilizzi per creare i tuoi lavori si basa principalmente sull’uso di pastelli, con i quali crei una microtessitura di segni che compongono il soggetto dell’opera. Un processo molto lento e, in un certo senso, “fisico”. Potresti parlare del modo in cui questa tecnica si relaziona agli aspetti poetici della tua pratica artistica?

CE: L’uso di certi materiali è dovuto in parte a miei personali limiti fisici (Esempio banale: mi sono precluse diverse sostanze chimiche per via di numerose allergie). Ho sempre usato strumenti minuti, come penne e matite. Si è trattato di una scelta istintuale, ma ci sono motivazioni interne nell’interesse per il disegno che con il tempo ho riconosciuto: utilizzo il segno in maniera microespressiva, una tessitura di segni che compongo a seconda di quella che è la natura di un soggetto o di quello che voglio esprimere. È un modo per riappropriarmi della realtà, che parte da un atteggiamento visivo quasi tattile, che costringe l’occhio ad accarezzare, ad invadere fisicamente, le superfici che esplora. Questo avvicinamento un po’ amorevole e un po’ violento si trasferisce nella restituzione tecnica dell’immagine: nella protrazione del tempo a contatto con il lavoro può esserci una carezza o un graffio, a volte arrivo al limite e rompo la carta. C’è una dimensione di insistenza ossessiva che mi porta a stare molto in contatto con il lavoro, e che produce attraverso la sovrapposizione di tanti livelli di segno la vitalità/intensità necessaria alla riuscita dell’immagine.

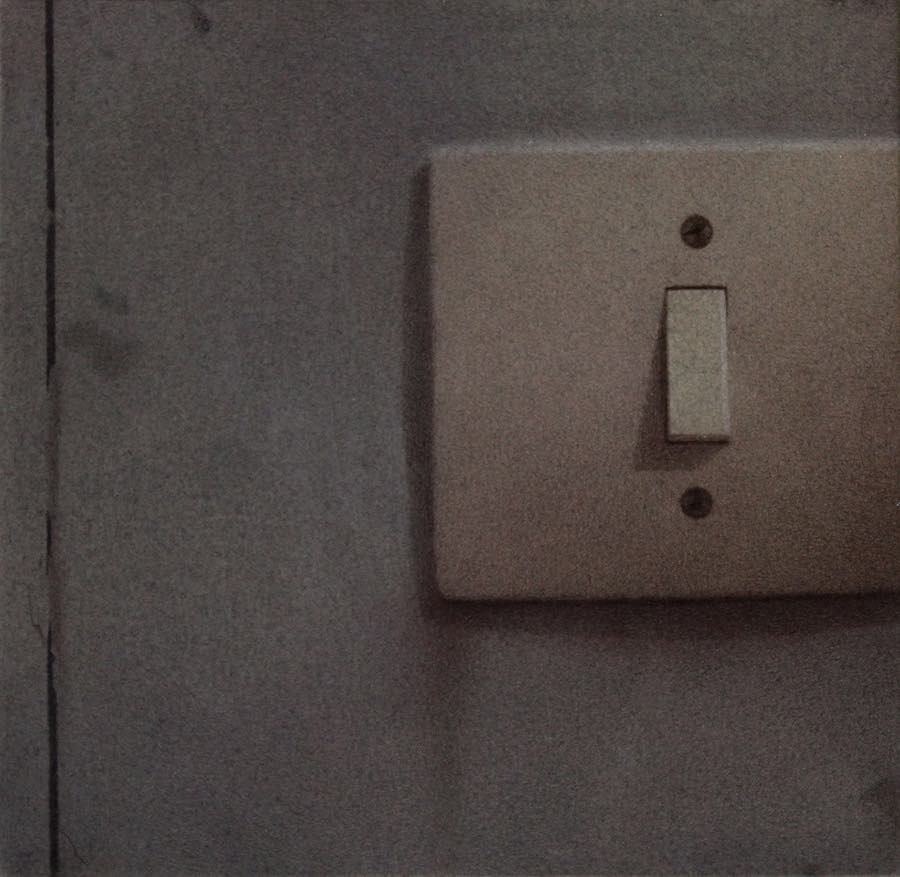

AM: C’è qualcosa di spiazzante nelle immagini che elabori, una tensione che mi viene da ricondurre al modo in cui rappresenti i tuoi soggetti: al fatto che le cose inanimate sembrano essere infuse di vita – spesso si tratta di apparecchi telefonici, rubinetti, lampadine o interruttori, quindi fonti di energia, agenti potenzialmente attivi, ma anche lenzuola stropicciate che ci appaiono insolitamente vitali nel gioco di luci creato dal panneggio – mentre i corpi risultano ritratti come pezzi di carne inermi. In sostanza, nei tuoi lavori, il confine tra morte e vita si mostra labile simulando il ritorno a una dimensione infantile, vorrei quindi chiederti di parlarci del rapporto tra gli elementi organici e inorganici che si alternano nei tuoi lavori e del ruolo della morte nella tua opera.

CE: Mi interessa come l’essere umano si comporta quando si trova in situazioni di costrizione, nel regime del “non posso”. Mi è capitato di trovarmici particolarmente spesso in passato per via di stati di salute non sempre ottimali, ma è una condizione che presto o tardi caratterizza l’esperienza di ogni vivente. Accade in questi casi che il pensiero cominci a vagare in modo irrazionale e intuitivo, come effettivamente fanno spesso (e sono dei gran maestri di questa pratica) i bambini. Penso che questo tipo di comportamenti del pensiero risponda al bisogno umano di dare senso alle cose, e uno dei modi fondamentali che abbiamo a disposizione per farlo è narrarle, nominarle, metterle in relazione. In fin dei conti, si tratta di creazione e di poesia. In quest’ottica un oggetto banale come un interruttore della luce diventa qualcosa di totalmente diverso, pur restando uguale a sé stesso. Si impregna di senso simbolico e diventa vivo al pari di un corpo, in un contesto quasi carnale di esplorazione. Il corpo è una cosa del mondo, e sono i punti di contatto tra il corpo e le cose che mi interessano, non il corpo o le cose in quanto tali. Gli oggetti parlano dei corpi e i corpi parlano di come si relazionano con essi – spesso sotto il segno del conflitto. La morte è una delle presenze nascoste dietro a ognuna di queste relazioni.

AM: Quella che metti in atto è una costruzione dell’immagine, o piuttosto una decostruzione, che non sembra rifarsi tanto a una tradizione pittorica. Le tue immagini frammentate, ravvicinate e parziali trovano maggiore riscontro in una visione di tipo cinematografico, configurandosi come inquadrature dal taglio brutale che sono riconducibili a uno sguardo filtrato.

CE: È un riferimento volontario perché il cinema è una fonte molto importante per me, mi arrischierei a dire, più della pittura. Per quanto riguarda la pittura sono legata davvero a pochi sceltissimi artisti: Odilon Redon o Fernand Khnopff, Giorgione, Mantegna, oppure i manieristi, il cui segno e uso del colore si slegano dalle briglie del naturalismo e si fanno espressivi. Per quanto riguarda il cinema invece posso citare il cinema di David Cronenberg, di Claire Denis, di Robert Bresson… Johnny got his gun di Dalton Trumbo forse è il film che più di tutti si avvicina ai miei temi e ai miei modi espressivi: rappresenta la costrizione e la finitezza umana, attraverso accorgimenti formali che permettono quasi di entrare nella pelle (o in quel che rimane…) del protagonista e patire con lui la sua condizione. Io guardo molto al cinema, al video, alla fotografia e in generale a ogni tipologia di interazione mediata perché mi sembra che oggi la maggior parte delle nostre interazioni avvenga attraverso questi mezzi. Amo lavorare sull’inquadratura perché mi aiuta a esprimere il senso di parzialità della mia visione. Nelle mie immagini gioca un ruolo importantissimo tutto ciò che è tagliato fuori, che è escluso e non si vede. Il senso di compressione dello spazio fisico creato dai primi piani produce una frustrazione dell’occhio, che si trova a vagare perché non trova nell’immagine tutto quello che cerca. Questa Inquietudine dello sguardo per me rappresenta la traduzione visiva della ricerca del senso del nostro stare al mondo. Nell’atto di scoprirsi si arriva a un punto zero, la pelle. La pelle catalizza per me il senso del limite, e in questo percorso di scoperta che mira al contatto, la ferita rappresenta la problematicità dell’involucro che si è, e la violenza che insidia ogni tentativo di contatto, anche visivo. Violenza e violazione hanno la stessa radice.

EC: Cecilia Alemani, curatrice della 59. Esposizione Internazionale d’Arte, in un’intervista ha dichiarato: “in mostra ci sono molti corpi che respingono una composizione o visione tradizionale”. SI tratta di corpi contenitori, corpi umani che si identificano come animali, corpi integrati con la tecnologia, corpi in fuga, etc. Potresti fornire una tua chiave di lettura sui temi della Biennale di quest’anno? Come si relazionano i tuoi corpi con le varie interpretazioni del corpo che si snodano lungo il percorso della mostra?

CE: Credo che con Il latte dei sogni Cecilia Alemani abbia voluto mettere al centro una serie di tendenze creative spesso considerate poco importanti o troppo poco incisive rispetto ai problemi che affliggono l’uomo contemporaneo. Parlo qui volutamente di uomo, al maschile, perché esprime bene il carattere dominante da cui questo tipo di pensiero origina. Porre l’attenzione sul corpo significa rimettere in discussione l’idea di cosa siamo e ripensare alle modalità con cui interagiamo tra noi e con le altre entità viventi e non viventi che affollano il mondo. Significa soprattutto scardinare i rapporti di potere che ci vincolano reciprocamente. Io lavorando con la vulnerabilità ho sempre cercato di contribuire a questo scardinamento.

La mia opera è stata inserita sapientemente in un’area della mostra molto intima, costellata di situazioni che chiedono una affine intimità per essere esperite al meglio, da Ovartaci al video di Nan Goldin, alla bellissima capsula Corpo orbita. Sono sentilmente molto vicina anche a diverse artiste ne La seduzione del cyborg: mi ha sempre affascinato l’idea dell’espansione corporea dell’Io nel rapporto con la macchina.

EC: Trovo molto curioso e interessante vedere il tuo lavoro condividere lo stesso spazio con Ovartaci (Luis Marcussen), che per me è stata una sorprendente scoperta. L’artista – come rilevato da Kathrin Busch – creava delle bambole per baciarle, toccarle e posizionarle su uno specchio, per vedervi il proprio sé immaginario. Pensi che il tuo lavoro possa avere delle affinità con quello di quest’autore?

CE: Non c’è una correlazione diretta con il lavoro di Ovartaci, ma vi sono punti di contatto. Le sue figure hanno qualcosa di alieno, probabilmente c’è un sentimento di non appartenenza e un tentativo di riappropriazione, dove gioca un suo ruolo anche il senso del tatto. Vi è uno sforzo di ricostruzione di un mondo che è andato in pezzi, e la volontà di esplorarne i limiti fisici.

AM: Complessivamente si rileva un certo clima surreale nelle tue opere che appaiono sfumate in quanto sfuggono a una collocazione chiara nel tempo e nello spazio, potrebbero infatti essere immagini di figure, reali o inventate, visioni, sogni, finzioni; vi è però un tuo lavoro che si riferisce a un preciso fatto di cronaca che ha acceso il dibattito politico in Italia, il caso di Stefano Cucchi. Vorrei che ci parlassi di come questo si inserisce nella tua pratica e, più in generale, della relazione tra realtà e immaginazione nel tuo lavoro.

CE: Nel mio lavoro c’è sempre un rapporto estremamente stretto con il reale – o meglio – con quella che è la mia percezione del reale. Sono sempre rimasta fedele a una modalità che ho adottato sin da bambina: quella di fare del disegno il mio mezzo prediletto per conoscere il mondo. Tuttavia il riferimento alla realtà non è mai pedissequo, e mai completamente subordinato alle eventuali immagini di cui mi servo per comporre le mie. Questo avviene anche nel caso delle due opere che hai menzionato, che ho realizzato partendo da una serie di fotografie dell’autopsia del corpo martoriato di Stefano Cucchi. La famiglia aveva pubblicato quelle foto per denunciare le violenze da lui subite in carcere, e io le avevo raccolte come faccio per molti altri casi di cronaca perché mi interessa molto come le situazioni violente vengono espresse e recepite. Spesso evito di utilizzare questo tipo di immagini troppo riconoscibili per non alimentare le dinamiche voyeuristiche che la loro diffusione già scatena, e Infatti quando questi lavori sono stati esposti non ho esplicitato né nel titolo né nel testo l’identità dei frammenti rappresentati. Ad ogni modo in questo caso tale diffusione era stata fortemente voluta al fine di rivendicare una giustizia negata, e quel corpo sofferente è diventato un simbolo ancora oggi molto potente.

Questions of Surface. Conversation with Chiara Enzo

Interview by Alessandra Maccari and Elena Coco —

“Focusing on the body means questioning the idea of what we are and rethinking the ways in which we interact with one another and other living and nonliving things that populate the world. This means principally, dismantling the relationships of power that reciprocally bind us.” With these words Chiara Enzo (Venezia, 1989) – artist featured in the 59. Esposizione Internazionale d’Arte Contemporanea di Venezia, Milk of Dreams, curated by Cecilia Alemani– introduces us to the themes of vulnerability, a sense of lacking, and of limitation that she explores in her artistic process. The following dialogue looks to highlight aspects of her work on occasion of her participation in the upcoming collective show Small Fixations at the Fondation ICA Milan.

ALESSANDRA MACCARI: Let’s start by reflecting on the way in which you display your work where often we find a visual dialogue between different pieces–as in the case of the installation of Conversation Piece–an ideal conversation, and one that alters depending on the project. One can find themself standing before an ordered grid, a cloud of images, a parade of drawings or the juxtaposition between two paintings. We can lose ourselves in our attempt to find a connection, in hypothesizing a sequence. I want to ask then if you conceive of your work as unique pieces, as an autonomous series, or if there is a continuity that renders the meaning of each work indefinable.

CHIARA ENZO: My intent has always been to consider each work as a world unto itself. The paintings must be able to be autonomous, but at the same time they also take part in a whole, where each communicates and references back to all the other images. It is the sense of lacking, of limitation, characterized in each work that ignites this communication; a sense of lacking that forever remains unfulfilled. It is the gaze embodied in each work, limited and wanting to express its limitation and lack of clarity towards the world. For me, my artistic practice has always meant measuring myself with power. The power of understanding. To reach as far as possible with the gaze and to have an all-encompassing vision of the world; confronting myself with the matter and bending it to my will. I realized then that the more I pushed myself, the more everything would fall to pieces. I began to look at these fragments, to use them in an attempt to construct something out of them.

ELENA COCO: The intimate and violent gaze that emerges from your images seduces the observer, going on to create a relationship of a voyeuristic sort, ambiguous between the visitor and your paintings. Speaking earlier with you, we noted that often the subject is perceived as if your eye had immortalized the image with a magnifying lens, establishing in the observer the feeling one experiences in front of a blown-up image: almost as if evoking an uncanny effect.

CHIARA ENZO: I find what you are saying very interesting, but it is always a little unsettling receiving this response because I have not ever actually portrayed figures enlarged from reality– with the exception of a few rare cases. I think this happens because the images are thought up and constructed to pull one in, the physical movement acted out by the viewer in effect emulates that movement of a camera zoom. The human eye then arrives at a certain point, and it is there that I also tend to stop, myself. Also the close-up framing which I often use contributes to the creation of this illusion. The space at hand is almost completely occupied by the subject that then in relation seems magnified.

ELENA COCO: A rapid and superficial approach to your work by the viewer can easily mislead one as to the techniques you use. The process that you utilize to create your work is based principally on the use of pastels and colored pencils, with which you create a micro texturing of marks that compose the subject of the work. An extremely slow process and, in a certain sense, “physical”. Could you speak about the way in which your technique is related to the poetic aspects of your artistic practice.

CHIARA ENZO: The use of certain materials is due in part to my personal physical limits (for example, I have to exclude many different chemical substances for the numerous allergies that I have). I have always used small tools, like pens and pencils. It was an instinctual choice, but there are internal motivations to my interest in drawing that I have recognized over time: utilizing marks in a micro expressive manner, a texture of marks that I compose according to the nature of a subject or what I want to express. It is a way to take back possession of reality, that departs from a visual, almost tactile, attitude that compels the eye to caress and to physically invade the surface that it explores. This approach, a bit amorous and a bit violent, transfers itself in the technical restitution of the image: in the protraction of time and contact with the work it can be a caress or a scratch; sometimes I reach a limit and tear the paper. There is a dimension of obsessive insistence that brings me into close contact with the work, and that produces through the overlapping of many levels of mark making the vitality/intensity necessary for the success of the image.

AM: There is something unsettling in the images that you elaborate, a tension that I would link back to the way you represent your subjects. In how the inanimate objects seem to be infused with life–often dealing with telephones, faucets, lightbulbs and electrical outlets, that is, sources of energy, potentially active agents, but also wrinkled bed sheets that seem to come to life in a play of light created by drapery–while the figures are instead portrayed as frail pieces of flesh. In short, the boundary between death and life tends to disappear, simulating the return to a childlike dimension. I would like then to ask you to speak about the relationship between the body and the inanimate things that alternate in your work, and of the role that death plays.

CHIARA ENZO: I am interested in how human beings act when they find themselves in constrained situations, in the mindset of “I can’t”. I happened to find myself there quite often in the past due to health issues that were not always optimal, but it is a condition that sooner or later characterizes the experience of every living person. It happens in these cases that the thought begins to wander in an irrational and intuitive way, as children often do (being masters of this practice). I believe that this type of thinking responds to a human need to make sense of things, and one of the fundamental ways that we have at our disposal is to narrate, name and place things in relation to others. After all, we are talking about creation and poetry. From this perspective a banal object, such as a light switch, becomes something completely different, while itself still remaining fundamentally the same. It is imbued in symbolic meaning and takes life as if a human body, in a quasi carnal context of exploration. The body is a thing of the world, and it is the points of contact between the body and things that interest me–not simply the body or things by themselves. Objects speak of bodies and bodies speak of how they relate to objects, often under a sign of conflict. Death is one of the hidden presences behind each of these relations.

AM: What you apply is a construction of the image, or rather a deconstruction, that does non seem to refer much to a pictorial tradition. Your fragmented, close-up and partial images approach more a cinematographic vision, shots framed by a brutal cropping of their subject matter, attributable to a filtered gaze.

CHIARA ENZO: It is a voluntary reference because cinema is a very important source for me, I’d risk saying, more so than painting. As far as painting is concerned, I am linked to a very few select artists: Odilon Redon or Fernand Khnopff, Giorgione, Mantegna, or the mannerists whose mark making and use of color was liberated from the bridle of naturalism and allowed for expressivity. As far as cinema is concerned, I can reference the work of David Cronenberg, Claire Denis, Robert Bresson…Johnny got his gun by Dalton Trumbo is perhaps the film more than any other that touches on my themes and ways of expression. It represents the constriction of human finiteness, through formal measures that almost permit one to enter into the skin of the protagonist–or what remains of it…–and suffer his condition alongside him. I look often towards cinema, video and photography and in general at any type of mediated interaction because it seems to me that today the major part of our interactions happen through these mediums. I love working on the framing because it helps me to express the sense of partiality of my vision. In my images an important role is played by everything that is cut out, that is excluded and not seen. The sense of compression of physical space created by the foregrounding of the image produces a frustration of the eye, which finds itself wandering because it does not find everything that it is searching for. This restlessness of the gaze for me represents the visual translation of a search for meaning in the world. In the act of stripping one arrives at a zero point, the skin. The skin for me catalyzes a sense of limitation, and in the act of stripping aims at contact. The wound represents the problematic nature of our bodily shell, and the violence that undermines each attempt at contact (even of the visual). Violence and violation have the same root.

EC: Cecilia Alemani, curator of the 59th Esposizione Internazionale d’Arte titled The Milk of Dreams, in an interview had declared that “in the exhibition there are many bodies that reject a traditional composition or vision”. There are bodys as containers, human bodies that identify as animals, bodies integrated with technology, escaping bodies, etc. Could you provide your interpretation on the themes of this year’s Biennale? How do the bodies in your work relate to the various interpretations of bodies that are present throughout the exhibition?

CHIARA ENZO: I think that with The Milk of Dreams, Cecilia Alemani wanted to focus on a series of trends often considered of little importance, or too little incisive, with respect to the problems that afflict contemporary man. I’m speaking intentionally of man, of the masculine, because it expresses well the dominant character from which this type of thought originates. Focusing on the body means questioning the idea of what we are and rethinking the ways in which we interact with one another and other living and nonliving things that populate the world. This means, principally, dismantling the relationships of power that reciprocally bind us. Working with vulnerability, I have always attempted to contribute to this dismantling.

My work has been inserted knowingly in a very intimate area of the exhibition, surrounded by other works that require a similar intimacy to be experienced properly, from Ovartaci to Nan Goldin’s video, to the beautiful Corps Orbite capsule. I am also very close to various artists in Seduction of the Cyborg: I have always been fascinated by the idea of bodily expansion from the “I” in relation to the machine.

EC: I find it very curious and interesting seeing your work in the same space alongside Ovartaci (Luis Marcussen), that for me has been an astonishing discovery. The artist – as Kathrin Busch noted – created dolls to kiss, touch and position on a mirror to see their imaginary self in it. Do you think that your work can have an affinity with that of said artist?

CHIARA ENZO: There is not a direct correlation with the work of Ovartarci, but there are points in common. Their figures have something alien, probably there is a feeling of not belonging and an attempt at reclaiming, where the tactile sense also plays a role. There is an effort to rebuild the world that has gone to pieces, and the desire to explore its physical limits.

AM: There is a certain surreal atmosphere in your works that appear blurred as they escape a clear location in time and space, it could be images of real or invented figures, it could be visions, dreams, or fictions. However, there is a work of yours that refers to a particular news story– a story that had ignited political debate in Italy, the case of Stefano Cucchi. I would like it if you could speak about how this enters into your practice and, more in general, in the relation between reality and imagination in your work.

CHIARA ENZO: In my work there is always an extremely close relationship with the real–or better–with that which is my perception of the real. I have always been faithful to an attitude that I had adopted as a child: that of drawing as my preferred medium to understand the world. However, the reference to reality is not ever slavlish, and never completely subordinate to any eventual images which I may use to compose my own. This happens also in the case of the two works that you have mentioned, which I have made from a series of photographs of the autopsy of the battered body of Stefano Cucchi. The family had published those photos to denounce the violence he suffered in custody, and I had collected them–as I had in many other news stories–because I am interested in how violent situations are expressed and received. Often I avoid the use of these types of overly recognizable images in order to avoid feeding the voyeuristic dynamic that the sharing of them already arouses. In fact, when these works were shown I did not explicitly say in the title nor in the text the identity of the representational fragments. In any case, this diffusion was strongly desired in order to claim a denied justice, and that suffering body has become a symbol that is still very powerful today.

Translation by John Michael McLaughlin.