English text below —

All’inizio c’è un numero. Cinque cifre: 00970. Un codice telefonico, un prefisso internazionale, una linea da comporre per raggiungere una terra che oggi, sotto i nostri occhi, viene rasa al suolo. Una cifra minima, quasi insignificante nella sua apparenza numerica, eppure carica di vita, di voci, di lutti, di ostinazioni. 00970 è il numero che precede ogni chiamata alla Palestina. Ma è anche la chiamata stessa, interrotta, disturbata, trascurata. È il rumore bianco dell’indifferenza, il silenzio che avanza quando le immagini perdono presa sul reale, e la realtà si trasforma in polvere, macerie, corpi dispersi.

La mostra in corso da ORDET a Milano sino al 20 settembre raccoglie venti opere di artiste e artisti palestinesi o appartenenti alla diaspora. Non un’esposizione tematica, né un percorso pedagogico, ma un gesto collettivo di contro-narrazione. Le immagini in movimento — film, video, suoni, voci — diventano geografie affettive, archivi spezzati, fantasmi che tornano a chiedere ascolto. In un tempo in cui Gaza brucia, sotto le bombe e le menzogne, 00970 apre una fenditura nel presente: non per consolare, ma per trattenere ciò che resiste. L’immagine non come testimonianza, ma come eco, frammento, incrinatura.

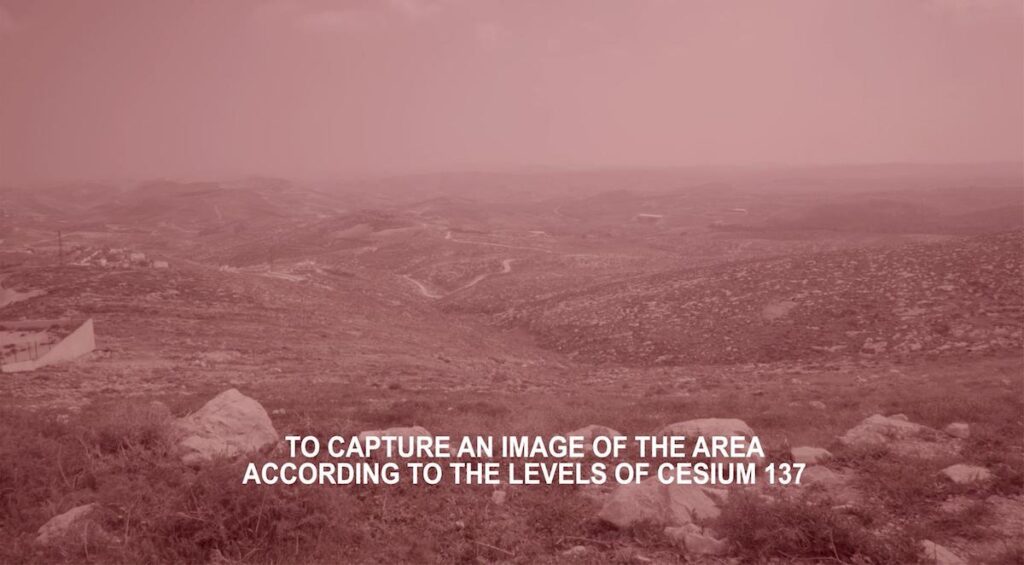

Le opere non illustrano la Palestina: la abitano nel tempo dislocato della memoria, della perdita, del ritorno impossibile. In We Have Always Known the Wind’s Direction,(2019-2020) Inas Halabi indaga la possibile sepoltura di scorie nucleari nel sud della Cisgiordania. Il cesio-137, invisibile e tossico, è la materia di un’ossessione che non può emergere pienamente: le parole sono frammentate, i paesaggi inquieti, la rappresentazione stessa messa in crisi. Halabi lavora nel punto cieco, là dove l’immagine si svuota e ciò che manca diventa visibile. Come nelle riflessioni di Ariella Azoulay — teorica e storica della fotografia, le cui ricerche sull’archivio coloniale, la cittadinanza visiva e le politiche della memoria mettono a fuoco ciò che viene sistematicamente rimosso o silenziato — anche il lavoro di Halabi si colloca in quello spazio critico dove l’immagine non mostra, si ritrae, lascia vuoti. Entrambe interrogano le condizioni della visibilità e della memoria: se per Azoulay l’assenza diventa il punto d’innesco di una contro-narrazione, Halabi agisce proprio in quel punto cieco, dove l’invisibile insiste e finisce per dire più del visibile.

Anche We Began by Measuring Distance (2009) di Basma al-Sharif racconta un fallimento del visivo: un gruppo misura distanze, registra, osserva — ma la distanza stessa diventa impossibile da quantificare. È lo spazio della diaspora, della sospensione, dell’irreparabile, una distanza che non si cancella, ma si attraversa come un paesaggio interno.

Ed è in quella stessa logica dell’esilio che si inscrive 31°42’49.5”N 35°10’13.9”E (2023) di Francisca Khamis Giacoman: la casa della famiglia ad Al-Makhrour non esiste più, sopravvive solo nei racconti orali e nei tracciati digitali di un GPS. Come ricorda Edward Said, l’esilio non è solo condizione di sradicamento, ma anche luogo di enunciazione — uno sguardo disallineato che decostruisce l’idea di appartenenza come radicamento esclusivo, e ne fa narrazione diasporica. Ovunque straniero, ma mai senza sguardo critico: così si delinea, in Edward Said, la possibilità di abitare il mondo da una frattura, ed è da quella stessa frattura che l’opera di Khamis Giacoman riattiva la memoria, trasformando l’assenza in una geografia affettiva e politica.

Il ritorno, in questi lavori, è sempre mediatizzato, impossibile. In Your father was born 100 years old, and so was the Nakba (2018) di Razan AlSalah, una nonna torna a Haifa solo attraverso Google Street View che promette accesso, ma restituisce assenza; cartografa ma disloca; mappa ma cancella. È un viaggio congelato: fotografie sgranate, strade immobili, una Palestina ridotta a interfaccia. Un rimando laconico a ciò che oggi, a Gaza, viene bombardato anche nella sua forma simbolica: una topografia emotiva che viene smantellata sistematicamente pezzo dopo pezzo, come se il paesaggio potesse essere cancellato dalla memoria insieme ai suoi luoghi. AlSalah — artista e filmmaker palestinese attiva tra Beirut e Montréal — lavora proprio su questo confine poroso tra corpo, tecnologia e memoria diasporica. Nelle sue opere, spesso costruite con found footage, VR e archivi digitali, l’immagine diventa luogo instabile, frammento di un ritorno impossibile. Il lavoro presentato in questa sede è anche una riflessione sulla natura coloniale degli strumenti di visione: il paesaggio palestinese diventa un campo conteso non solo geopoliticamente, ma anche percettivamente — una contro-cartografia affettiva, dove la visione si incrina e l’immagine restituisce il vuoto dell’espulsione.

Refusing to Meet Your Eye (2022) di Huda Takriti si apre con una sottrazione radicale, una mancanza che diventa punto d’origine: una fotografia completamente nera, l’unica immagine sopravvissuta al dirottamento aereo compiuto da Leila Khaled nel 1969. Un documento negato, opaco, che diventa punto di partenza per interrogare non solo le immagini, ma anche il loro potere e i loro fallimenti. È in quel nero che la storia si condensa, si ritrae, e insieme si carica di potenziale critico.

Come Jacques Rancière mostra ne La partizione del sensibile (2000) e in The Politics of Aesthetics (2004), è proprio l’estetica—intesa come regime del sensibile—a stabilire ciò che può essere visto, detto, ascoltato e chi ha accesso a questo spazio di visibilità. Takriti agisce proprio su questa soglia: mette in crisi le gerarchie dello sguardo, lavora per ridistribuire l’apparizione, per spezzare la grammatica visiva del dominio. Come molte altre voci in questa mostra, fa dell’assenza non una mancanza, ma una forma attiva di presenza: uno spazio politico che resiste alla narrazione egemonica e ne disarticola l’impianto.

Nel cuore dell’esposizione, come un contrappunto ai vuoti e agli errori dell’archivio, pulsa il lavoro di Emily Jacir su Tel al Zaatar (1977): una ricostruzione archivistica delle riprese girate nel 1977 da Monica Maurer all’interno di un campo profughi palestinese in Libano, teatro di un massacro ormai relegato ai margini della memoria storica. Jacir non restituisce semplicemente un documento ma apre una ferita. Un tempo che continua a sanguinare attraverso l’immagine rendendola visibile senza spettacolarizzarla, come un atto di riparazione e di amore. Il suo gesto è radicalmente politico e profondamente affettivo.

Nel suo Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism (Verso Books, 2019), Ariella Azoulay invoca il bisogno urgente di “disimparare l’impero” — un atto di ripensamento radicale delle immagini e dei gesti che le producono -, a sospendere le modalità conoscitive e percettive che l’ordine coloniale ha reso familiari, e che continuano a modellare gli archivi, gli sguardi, i corpi. La storia non è un dato chiuso, ma un campo potenziale da riaprire, dissodare, disimparare. L’archivio imperiale — fondato sulla violenza, sull’espropriazione e sulla cancellazione — può essere smontato solo attraverso un atto di coabitazione con ciò che è stato messo a tacere. Azoulay invita a pensare la storia non come un racconto lineare ma come uno spazio in sospensione, in cui la giustizia si gioca nel presente, attraverso la restituzione del visibile e dell’ascoltabile, a chi ne è stato espulso. Non si tratta di produrre nuove immagini, ma di ripensare le condizioni stesse della visibilità: i gesti che portano l’immagine nel mondo, le relazioni che essa implica, i silenzi che impone o interrompe. È esattamente ciò che fa Jacir: riattraversa le rovine dell’archivio non con nostalgia, ma con ostinazione. Le sue immagini non commemorano, resistono. Non riempiono un vuoto, ma lo espongono — come una fenditura aperta nel tempo, contro l’erosione dell’oblio.

Altri lavori si muovono lungo confini più porosi, tra umano e non umano, tra museo, corpo, rovina. Nel solco di una critica delle istituzioni visive, Am I the Ageless Object at the Museum? (2018) di Noor Abuarafeh intreccia zoo, cimiteri e istituzioni museali per interrogare l’atto stesso del conservare: cosa viene protetto, cosa viene esposto, cosa viene dimenticato? L’artista compone una genealogia del controllo visivo e disciplinare, in cui il corpo vivo diventa oggetto, reliquia, tassonomia — corpo esposto ma non ascoltato.

In Hold Breath (2025), Basel Abbas e Ruanne Abou-Rahme ci portano al limite del respiro: tra trattenimento e collasso, tra presenza e dissolvenza. Un’opera che si dispiega come poema visivo, in cui la Palestina appare come corpo esaurito ma non domato, che trattiene ancora — per un istante sospeso — il fiato, come chi sa che respirare ancora è già un atto contro il dominio.

Dina Mimi, con Thousand Thrashing Arms (2024), lavora sul corpo come punto di tensione e desiderio frustrato. Prende le parole di Fanon sul corpo colonizzato e le trasforma in sogno visivo, in desiderio spezzato: corsa, salto, nuoto. Il movimento, qui, è un gesto di liberazione abortita, o forse solo invocata nel linguaggio dei pixel.

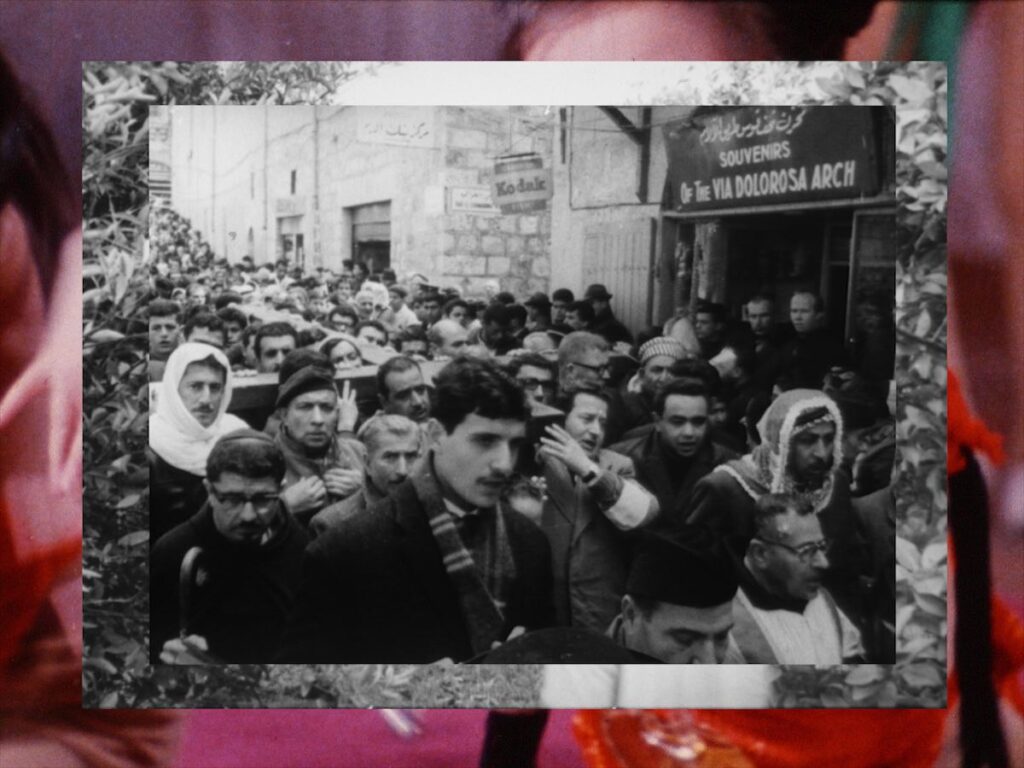

In un altro registro, ma nella stessa tensione verso una restituzione parziale, frammentata e inquieta della storia, si collocano le opere di Oraib Toukan, TaysirBatniji e Marwa Arsanios. Via Dolorosa (2021) di Toukan lavora sul gesto del ri-montaggio come forma di attivazione dell’archivio dimenticato, accostando materiali d’epoca e commenti teorici in una processione visiva che è anche processuale, meditativa, quasi liturgica. Batniji, con Transit (2004), offre invece un contro-racconto muto e lento: una sequenza di fotografie clandestine, sgranate, girate tra Il Cairo e Rafah, che documentano l’attesa, la stasi, l’impossibilità del movimento. Il tempo, nei suoi fotogrammi, è una ferita.

Arsanios, con Have You Ever Killed a Bear or Becoming Jamila (2013), rievoca invece la figura della combattente algerina Djamila Bouhired come spettro mediale: cinema, stampa egiziana, propaganda e diserzione ideologica si intrecciano per interrogare i dispositivi iconici del femminile rivoluzionario. Il suo lavoro si colloca là dove l’archivio diventa finzione, dove la soggettività si costituisce nel corpo di un’immagine prodotta da altri.

La tenacia silenziosa torna nei corpi femminili che danzano, che cantano, che portano con sé i racconti popolari di una terra fatta di pozzi, lutti, sparizioni. In Our songs were ready for all wars to come (2021), Noor Abed costruisce una coreografia del dolore e della sopravvivenza, dove il canto resta l’unico linguaggio possibile quando le parole si spezzano. L’artista — che lavora tra Ramallah e la diaspora, intrecciando cinema, performance e pratiche comunitarie — si muove lungo la soglia tra rituale e resistenza, tra memoria orale e immaginazione politica. Le sue protagoniste non interpretano un ruolo: incarnano una storia collettiva, stratificata, che si trasmette attraverso i gesti, le voci, i ritmi che precedono la parola scritta. Abed si ispira alle pratiche coreutiche e vocali femminili del Levante, a cerimonie che mescolano lamento, festa e preghiera, recuperandole come forme di archivio vivente. Nella Palestina di oggi, dove la voce è sistematicamente interrotta, cancellata, criminalizzata, questo canto si impone come un atto di insubordinazione radicale. Non c’è documento, qui, ma presenza. Non c’è narrazione lineare, ma evocazione corale. È il corpo stesso, nella sua esposizione fragile e testarda, a diventare il luogo in cui la storia resiste.

E poi c’è il suono, che taglia il silenzio come una lama: assordante nella sua assenza. Starry Night (2006) di Mazen Kerbaj è un’improvvisazione al limite dell’assurdo: la tromba dialoga con le esplosioni durante il bombardamento di Beirut. L’artista registra tutto dal balcone di casa: la città brucia, ma il suono resiste. In un gesto simile a quello che oggi accade a Gaza, dove le case crollano ma le voci restano, testimoniano, scrivono, documentano finché possono.

ll suono si fa di nuovo materia interrogativa in My Pain is Real (2010)di Ali Cherri che mette alla prova la nostra soglia percettiva, assuefatta al dolore altrui. Possiamo ancora guardarlo davvero? Possiamo ancora sentirlo, farcene carico? In un mondo in cui le immagini di guerra scorrono ininterrotte sugli schermi — filtrate, moltiplicate, neutralizzate — cosa resta dell’empatia, dell’ascolto, della capacità di risposta? Artista visivo e regista libanese, Ali Cherri lavora da anni sul rapporto tra archeologia, trauma e potere, interrogando le narrazioni che legano il corpo alla storia e le immagini alla violenza. La sua pratica — che si muove tra video saggio, installazione e performance — esplora i resti, i fossili, le ferite aperte del presente. In My Pain is Real, l’artista si confronta direttamente con l’impossibilità di rappresentare il dolore senza esporlo al rischio del consumo, senza ridurlo a una merce visiva. Il dolore qui non è spettacolo, ma materia instabile, opaca, che ci chiede di rinegoziare la nostra posizione di spettatori. Achille Mbembe, nel suo Necropolitics (Duke University Press, 2019), ci offre una chiave teorica per comprendere l’estensione del potere contemporaneo oltre la gestione della vita, fino al dominio sui corpi destinati alla morte. In continuità con il paradigma biopolitico foucaultiano, ma spingendolo verso i suoi limiti estremi, Mbembe mostra come la sovranità si eserciti oggi attraverso l’abbandono, l’esposizione, l’assoggettamento differenziale dei corpi. Chi può morire, chi può essere visto morire, chi può raccontarlo: questa è la logica necropolitica che organizza il visibile e l’invisibile nei conflitti coloniali e postcoloniali del nostro tempo. È il potere di definire quali vite sono degne di lutto, di memoria, di attenzione, e quali invece possono essere cancellate senza conseguenze, è la grammatica che si dispiega a Gaza in tempo reale, sotto gli occhi del mondo, senza mediazioni, senza vergogna: il dolore viene prodotto e mostrato nell’immediatezza dell’evento, ma raramente ascoltato e l’immagine non restituisce la presenza, ma l’abbandono. In questo contesto, il lavoro di Cherri si fa contropotere: non documenta, ma incrina; non illustra, ma chiede. Ci costringe a restare nello spazio scomodo tra la visione e la responsabilità, tra ciò che vediamo e ciò che scegliamo di non vedere.

Eppure, contro questa logica di morte, Foragers (2022)di Jumana Manna riporta la resistenza nei gesti più quotidiani: racconta la raccolta illegale di za’atar (una pianta simile al carciofo) e ‘akkoub (timo) come gesto di appartenenza e insubordinazione. Un’erba può essere politica. Un seme può contenere una rivolta. Le scene di cucina, le fughe dai ranger, i processi legali mostrano come l’ecologia sia campo di contesa coloniale. Ma anche di resilienza. Di radicamento. La terra, qui, non è oggetto di proprietà: è corpo vivo, memoria ancestrale, voce sotterranea. Due opere, infine, agiscono come deragliamenti silenziosi all’interno del tessuto urbano e delle sue strutture di proprietà e memoria. In 30kg Shine (2017) Shadi Habib Allah costruisce un viaggio notturno nei livelli nascosti di Gerusalemme tra fantasmi del 1936 e lavoratori invisibili. Nature Morte (2008) di Akram Zaatari, invece, ci mostra un’interruzione silenziosa: due uomini che si osservano, esitano, e non combattono. Il gesto che non si compie, il corpo che si ritrae, diventa qui allegoria di una resistenza in tensione, tra generazioni e tra ideologie. Il paesaggio, anch’esso testimone, registra silenzioso questa sospensione.

A legare molte di queste opere è anche ciò che Hamid Dabashi, in Palestine, Liberation, and the Arab Uprisings (Palgrave Macmillan, 2020), ha definito la condizione transnazionale palestinese: una condizione diasporica e resistente che eccede il modello dello Stato, che attraversa confini, media e linguaggi, rendendo la questione palestinese non solo un fatto locale, ma una griglia critica per leggere le dislocazioni del potere e le forme di solidarietà emergenti su scala globale.

Le opere di 00970 non cercano di rappresentare una nazione, ma di rendere visibile una grammatica dell’esilio: una serie di gesti, voci, intonazioni che parlano da una soglia. Da un altrove. Non si tratta di affermare un’identità, ma di costruire uno spazio di ascolto.

Anche il documentario, qui, viene messo in crisi. Talaeen a Junuub (1993), il lavoro realizzato da Walid Raad e Jayce Salloum, affronta la resistenza in Sud Libano non tanto attraverso una narrazione diretta o lineare, quanto smontando progressivamente le convenzioni stesse del linguaggio documentario: il punto di vista, la verità, il montaggio come garanzia di senso. L’opera scarta ogni pretesa di oggettività, assumendo la forma di un racconto in frammenti, dove i materiali raccolti convivono con le loro opacità, le loro contraddizioni, i vuoti. È una linea di pensiero che trova risonanza nelle riflessioni di Trinh T. Minh-ha, regista e teorica vietnamita-americana, secondo cui “non si dà rappresentazione innocente”: ogni immagine comporta una presa di posizione, ogni montaggio è già un gesto critico. Il documentario, anziché spiegare, si interroga. Anziché restituire il reale, lo incrina.

In 00970, le opere non gridano. Resistono. Alcune in silenzio, altre per via di canti, testimonianze, montaggi ellittici. Il dolore non è mai spettacolarizzato, ma trattenuto, interrogato, disarticolato. La giustizia selettiva e arbitraria, di cui parla il comunicato stampa, trova qui la sua controparte estetica: una pratica visiva che rifiuta la retorica, che non semplifica, che non educa. Una pratica che invita a restare.

In un tempo in cui i numeri superano la soglia dell’umano —decine e decine di migliaia di morti, centinaia di giornalisti, operatori umanitari, artisti uccisi — questa mostra è un atto di resistenza. Di lutto attivo. Di testimonianza non neutralizzabile. Rancière lo ha detto con chiarezza: la politica dell’arte non risiede nei messaggi, ma nella forma che dà visibilità al mondo. 00970 produce visibilità dove si vorrebbe solo buio.

Guardare non basta più. È tempo di ascoltare, di raccogliere, di portare memoria. E anche di agire. Perché ogni opera è una chiamata. E ogni chiamata, oggi, è un’urgenza — un numero da comporre, un segnale che ci raggiunge da una terra in frantumi. Rispondere non è più un’opzione.

Cover: Ali Cherri, My Pain is Real, still, 2010 – Courtesy the artist and Galerie Imane Farès, Paris

00970: Moving Images from the Threshold of a Dislocated Land

Text by Rita Selvaggio —

It begins with a number. Five digits: 00970. A phone code, an international prefix, a line to dial in order to reach a land that, before our eyes, is being razed to the ground. A minimal figure, seemingly insignificant in its numerical form, and yet charged with life, with voices, with mourning and defiance. 00970 is the number that precedes every call to Palestine. But it is also the call itself — interrupted, distorted, neglected. It is the white noise of indifference, the advancing silence that rises when images lose their grip on reality, and reality turns to dust, to rubble, to scattered bodies.

The exhibition currently on view at ORDET in Milan, until September 20, brings together works by Palestinian artists and those from the diaspora. Not a thematic display, nor a pedagogical journey, but a collective gesture of counter-narration. The moving images—films, videos, sounds, voices—become affective geographies, broken archives, ghosts returning to demand attention. In a time when Gaza is burning, under bombs and lies, 00970 opens a fissure in the present: not to console, but to hold on to what resists. The image not as testimony, but as echo, fragment, fracture.

The works on view do not illustrate Palestine: they inhabit it, within the dislocated time of memory, of loss, of impossible return. In We Have Always Known the Wind’s Direction (2019–2020), Inas Halabi investigates the potential burial of nuclear waste in the south of the West Bank. Caesium-137—both invisible and toxic—is the matter of an obsession that cannot fully surface: words are fractured, landscapes are restless, and representation itself is thrown into crisis. Halabi works within the blind spot, in that space where the image empties out and what is missing begins to appear.

As in the writings of Ariella Azoulay—theorist and historian of photography, whose research into the colonial archive, visual citizenship, and the politics of memory brings into focus what is systematically erased or silenced—Halabi’s work, too, occupies that critical zone where the image does not reveal, but withdraws, leaving voids. Both interrogate the conditions of visibility and remembrance: if for Azoulay absence becomes the ignition point of a counter-narrative, Halabi operates precisely within that blind spot, where the invisible insists, and ends up saying more than what can be seen.

We Began by Measuring Distance (2009) by Basma al-Sharif also speaks of a visual failure: a group measures distance, records, observes—yet the very idea of distance becomes impossible to quantify. It is the space of diaspora, of suspension, of the irreparable: a distance that cannot be erased, but must be traversed like an inner landscape.

It is within that same logic of exile that 31°42’49.5”N 35°10’13.9”E (2023) by Francisca Khamis Giacoman is inscribed: the family home in Al-Makhrour no longer exists, surviving only through oral accounts and the digital traces of a GPS coordinate. As Edward Said reminds us, exile is not merely a condition of uprootedness, but also a site of enunciation—a disaligned gaze that deconstructs the idea of belonging as exclusive rootedness, and recasts it as diasporic narration. Always a stranger, yet never without a critical gaze: this is how Said outlines the possibility of inhabiting the world from within a fracture—and it is from that very fracture that Khamis Giacoman’s work reactivates memory, transforming absence into an affective and political geography.

Return, in these works, is always mediated—always impossible. In Your father was born 100 years old, and so was the Nakba (2018) by Razan AlSalah, a grandmother returns to Haifa only through Google Street View: a tool that promises access but delivers absence; that maps while it dislocates; that charts even as it erases. It is a frozen journey: pixelated images, motionless streets, a Palestine reduced to interface. A laconic echo of what is now being bombed in Gaza, even in its symbolic form: an emotional topography systematically dismantled, piece by piece, as if the landscape could be erased from memory along with the places it holds. AlSalah—a Palestinian artist and filmmaker working between Beirut and Montréal—operates precisely on this porous threshold between body, technology, and diasporic memory. In her works, often built through found footage, VR, and digital archives, the image becomes an unstable site, a fragment of an impossible return. The work presented here is also a meditation on the colonial nature of visual tools: the Palestinian landscape becomes a contested field not only geopolitically, but perceptually—a counter-cartography of affect, where vision falters and the image reflects the void left by expulsion.

Refusing to Meet Your Eye (2022) by Huda Takriti begins with a radical subtraction, an absence that becomes a point of origin: a completely black photograph, the only image that survived the 1969 plane hijacking carried out by Leila Khaled. A denied, opaque document that becomes the starting point for questioning not only images themselves, but also their power—and their failures. It is within that blackness that history condenses, withdraws, and simultaneously becomes charged with critical potential.

As Jacques Rancière argues in The Distribution of the Sensible (2000) and The Politics of Aesthetics (2004), it is aesthetics—understood as a regime of the sensible—that determines what can be seen, said, heard, and who is granted access to that space of visibility. Takriti works precisely on this threshold: she unsettles the hierarchies of the gaze, reconfigures the field of appearance, and fractures the visual grammar of domination. Like many other voices in this exhibition, she turns absence not into a lack, but into an active form of presence: a political space that resists hegemonic narration and dismantles its very framework.

At the heart of the exhibition, as a counterpoint to the voids and errors of the archive, pulses Emily Jacir’s work on Tel al Zaatar (1977): an archival reconstruction of footage shot in 1977 by Monica Maurer inside a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon, the site of a massacre now largely pushed to the margins of historical memory. Jacir does not merely retrieve a document—she opens a wound. A time that continues to bleed through the image, rendering it visible without spectacle, as an act of repair and of love. Her gesture is radically political and deeply affective.

In her Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism (Verso Books, 2019), Ariella Azoulay calls for the urgent need to “unlearn empire”—a radical rethinking of images and of the gestures that produce them; a suspension of the epistemic and perceptual modes rendered familiar by the colonial order and still shaping our archives, gazes, and bodies. History is not a closed account, but a potential field—something to be reopened, unsettled, unlearned. The imperial archive—built on violence, expropriation, and erasure—can only be dismantled through an act of cohabitation with what has been silenced.

Azoulay urges us to conceive of history not as a linear narrative, but as a suspended space, where justice is enacted in the present through the restitution of the visible and the audible to those from whom it has been withheld. It is not a matter of producing new images, but of rethinking the very conditions of visibility: the gestures that bring an image into the world, the relations it enacts, the silences it imposes or breaks.

This is precisely what Jacir does: she moves through the ruins of the archive not with nostalgia, but with determination. Her images do not commemorate; they resist. They do not fill a void; they expose it—as an open rupture in time, standing against the erosion of forgetting.

Other works in the exhibition move along more porous boundaries—between the human and the non-human, the museum, the body, the ruin. In the wake of a critique of visual institutions, Am I the Ageless Object at the Museum? (2018) by Noor Abuarafeh weaves together zoos, cemeteries, and museum institutions to question the very act of preservation: what is protected, what is displayed, what is forgotten? The artist composes a genealogy of visual and disciplinary control, in which the living body becomes object, relic, taxonomy—a body exposed, but not heard.

In Hold Breath (2025), Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme bring us to the edge of breath itself: between restraint and collapse, between presence and fading. The work unfolds as a visual poem, in which Palestine appears as an exhausted yet untamed body, still holding—if only for a suspended instant—its breath, like one who knows that to breathe again is already an act of resistance.

Dina Mimi, in Thousand Thrashing Arms (2024), works with the body as a site of tension and frustrated desire. She takes Fanon’s words on the colonised body and transforms them into visual dream, into broken longing: running, leaping, swimming. Movement here becomes a gesture of aborted liberation—or perhaps one merely invoked in the language of pixels.

In a different register, but animated by the same drive toward a partial, fractured, and unsettled restitution of history, are the works of Oraib Toukan, Taysir Batniji, and Marwa Arsanios. Via Dolorosa (2021) by Toukan explores the gesture of re-editing as a form of reactivating the forgotten archive, juxtaposing period footage with theoretical commentary in a visual procession that is also processual, meditative, almost liturgical. Batniji, in Transit (2004), offers a slow, mute counter-narrative: a sequence of clandestine, grainy photographs taken between Cairo and Rafah, documenting waiting, stillness, the impossibility of movement. In his frames, time itself is a wound.

Arsanios, with Have You Ever Killed a Bear or Becoming Jamila (2013), conjures the figure of Algerian freedom fighter Djamila Bouhired as a mediated spectre: cinema, Egyptian print media, propaganda and ideological defection intertwine to question the iconic apparatus of revolutionary femininity. Her work inhabits the space where the archive turns to fiction, where subjectivity is shaped through an image produced by others.

Silent tenacity returns in the female bodies that dance, that sing, that carry with them the folk tales of a land made of wells, mourning, and disappearances. In Our Songs Were Ready for All Wars to Come (2021), Noor Abed composes a choreography of pain and survival, where song remains the only possible language when words break apart. The artist—working between Ramallah and the diaspora, weaving together film, performance, and community-based practices—moves along the edge between ritual and resistance, between oral memory and political imagination. Her protagonists do not play a role: they embody a layered, collective history, transmitted through gestures, voices, rhythms that precede the written word.

Abed draws on the choral and vocal traditions of Levantine women, on ceremonies that blend lament, celebration, and prayer—reviving them as forms of living archive. In today’s Palestine, where voice is systematically interrupted, silenced, criminalised, this song asserts itself as an act of radical insubordination. There is no document here, only presence. No linear narrative, but a choral evocation. It is the body itself—in its fragile and stubborn exposure—that becomes the site where history holds its ground.

And then there is sound, slicing through silence like a blade: deafening in its absence. Starry Night (2006) by Mazen Kerbaj is an improvisation bordering on the absurd: a trumpet in dialogue with explosions during the bombing of Beirut. The artist records everything from his balcony: the city burns, but sound persists. A gesture not unlike what is happening today in Gaza, where the houses collapse but voices remain, testify, write, document—for as long as they can.

Sound once again becomes interrogative matter in My Pain is Real (2010) by Ali Cherri, which tests the limits of our perceptual threshold, dulled by constant exposure to the pain of others. Can we still truly look at it? Can we still hear it—carry it, respond to it? In a world where images of war flow endlessly across screens—filtered, multiplied, neutralised—what remains of empathy, of listening, of the capacity to respond?

A Lebanese visual artist and filmmaker, Cherri has long worked at the intersection of archaeology, trauma, and power, interrogating the narratives that bind the body to history and images to violence. His practice—moving between video essay, installation, and performance—explores remnants, fossils, open wounds of the present. In My Pain is Real, he confronts the impossibility of representing pain without exposing it to the risk of consumption, without reducing it to a visual commodity. Pain here is not spectacle, but unstable, opaque matter—demanding that we renegotiate our position as spectators.

Achille Mbembe, in his Necropolitics (Duke University Press, 2019), offers a theoretical framework for understanding how contemporary power extends beyond the management of life to the control of bodies destined for death. In continuity with Foucault’s biopolitical paradigm, yet pushing it to its furthest limits, Mbembe shows how sovereignty now operates through abandonment, exposure, and the differential subjugation of bodies. Who may die, who may be seen dying, who may speak of it: this is the necropolitical logic that structures the visible and the invisible in the colonial and postcolonial conflicts of our time.

It is the power to decide which lives are grievable, memorable, worthy of attention—and which can be erased without consequence. It is the grammar unfolding in Gaza in real time, before the eyes of the world, without mediation, without shame: pain is produced and displayed in the immediacy of the event, but rarely listened to. The image does not return presence—it exposes abandonment.

In this context, Cherri’s work becomes counter-power: it does not document, but fracture; does not illustrate, but demand. It forces us to remain within the uneasy space between vision and responsibility, between what we see and what we choose not to see.

And yet, against this logic of death, Foragers (2022) by Jumana Manna brings resistance back into the most everyday gestures: it tells the story of the illegal gathering of za’atar (a plant similar to artichoke) and ‘akkoub (wild thyme) as acts of belonging and insubordination. An herb can be political. A seed can contain a revolt. Scenes of cooking, fleeing from rangers, courtroom trials—these all reveal how ecology is a site of colonial contestation. But also of resilience. Of rootedness. The land here is not a possession: it is a living body, ancestral memory, subterranean voice.

Two works, finally, act as silent derailments within the urban fabric and its structures of ownership and memory. In 30kg Shine (2017), Shadi Habib Allah constructs a nocturnal journey through the hidden layers of Jerusalem—among ghosts from 1936 and invisible workers. Nature Morte (2008) by Akram Zaatari, on the other hand, reveals a quiet interruption: two men look at one another, hesitate, and do not fight. The gesture that is withheld, the body that draws back, becomes here an allegory of resistance under tension—between generations, between ideologies. The landscape, too, bearing witness, silently registers this suspension.

What ties many of these works together is what Hamid Dabashi, in Palestine, Liberation, and the Arab Uprisings (Palgrave Macmillan, 2020), has defined as the Palestinian transnational condition: a diasporic and resistant condition that exceeds the framework of the nation-state, crossing borders, media, and languages—which to read dislocations of power and emergent forms of global solidarity.

The works in 00970 do not seek to represent a nation, but to make visible a grammar of exile: a constellation of gestures, voices, and inflections that speak from a place of transition. From an elsewhere. It is not about asserting an identity, but about constructing a space of listening.

Even the documentary form, here, is brought into crisis. Talaeen a Junuub (1993), the work created by Walid Raad and Jayce Salloum, addresses resistance in South Lebanon not through direct or linear narration, but by progressively dismantling the very conventions of documentary language: point of view, truth, montage as guarantor of meaning. The work rejects any claim to objectivity, assuming instead the shape of a fragmented narrative, where collected materials coexist with their opacities, contradictions, and absences.

This approach resonates with the thinking of Vietnamese-American filmmaker and theorist Trinh T. Minh-ha, who reminds us that “there is no such thing as innocent representation”: every image entails a position, every cut is already a critical gesture. Documentary, rather than explaining, begins to question. Rather than returning the real, it fractures it.

In 00970, the works do not shout. They withstand. Some in silence, others through songs, testimonies, elliptical montages. Pain is never sensationalised, but held, questioned, disarticulated. The selective and arbitrary justice mentioned in the exhibition statement finds here its aesthetic counterpart: a visual practice that refuses rhetoric, that does not simplify, that does not teach. A practice that invites us to remain.

In a time when numbers surpass the threshold of the human—tens of thousands dead, hundreds of journalists, aid workers, artists killed—this exhibition stands as an act of defiance. Of active mourning. Of testimony that cannot be neutralised. As Rancière has made clear: the politics of art does not lie in the messages it conveys, but in the form that renders the world visible. 00970 produces visibility where darkness is meant to prevail.

Looking is no longer enough. It is time to listen, to gather, to carry memory. And to act. Because every work is a call. And every call, today, is an urgency—a number to dial, a signal reaching us from a shattered land. To respond is no longer optional.