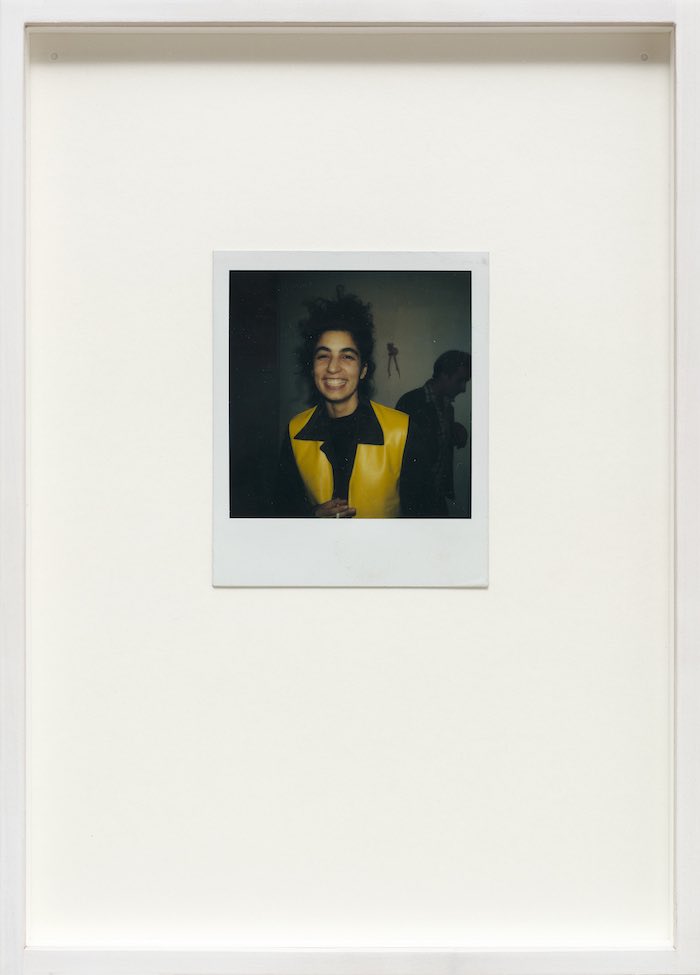

photo Credit ph. D.Lasagni

English version below —

Sara Benaglia / Mauro Zanchi: A distanza di 40 anni rispetto a quando hai cominciato a lavorare sulla found photography, quali sono le più interessanti derive che oggi si possono diramare dalla tua intuizione e da questo genere di sguardo? Come si può andare oltre, costruttivamente, l’attuale tendenza decisamente mainstream di chi lavora partendo dalla found photography?

Joachim Schmid: Il mio lavoro è una ricerca continua di cultura visiva con particolare attenzione alla fotografia non professionale. È un campo vasto e, sorprendentemente, c’è ancora un territorio non mappato. Se una parte di esso sia o meno “interessante” lo scopro solo dopo averci messo piede. Naturalmente non sono l’unico a lavorare in questo campo, e alcune opere basate sulla fotografia trovata possono essere ora compatibili con il mainstream del mondo dell’arte. Faccio il lavoro che desidero fare; né entrare a far parte del mainstream né prenderne le distanze giocano un ruolo nella mia mente.

SB/MZ: Quale è stata l’evoluzione di questa prassi?

JS: L’evoluzione del mio lavoro è stata ed è soggetta agli stessi fattori che caratterizzano l’evoluzione nel suo senso darwiniano. Si tratta di un processo irregolare, volatile e casuale, piuttosto che di uno sviluppo che segue una qualsiasi logica. Forse si potrebbe chiamare discontinuità continua. L’unico progresso è che cerco di limitare la ripetizione, in particolare evitando gli errori che ho commesso in precedenza.

SB+MZ: Come è cambiato l’approccio passando anche attraverso il rubinetto di Internet, dei motori di ricerca e l’inondazione di immagini?

JS: L’inondazione di immagini non è un fenomeno nuovo, si possono ripercorrere le tracce di questo tema tornando indietro per almeno un secolo. Ma i numeri sono esplosi, naturalmente, dopo che la fotografia digitale è diventata un passatempo popolare. La fusione di telefono e macchina fotografica è stata la spinta finale. Ora le fotografie sono il costante rumore di fondo di ogni attività umana. La cosa davvero cruciale, tuttavia, non è il numero di fotografie che vengono fatte, ma il fatto che molte di esse sono ora pubbliche. Una generazione fa la maggior parte delle fotografie si trovava in archivi privati, aziendali o governativi con un accesso molto limitato a un numero contingentato di persone. Ora un numero sempre crescente di immagini è accessibile praticamente a tutti. Il photo hosting online ha creato un ambiente visivo completamente nuovo. E il motore di ricerca lo rende gestibile, almeno in una certa misura. Tuttavia, la ricerca si basa sull’input verbale; molte foto vengono caricate senza didascalie o descrizioni e per questo motivo non sono incluse nei risultati della ricerca. Così i siti di hosting fotografico online si sono trasformati in enormi discariche digitali di rifiuti visivi. Tutto questo ha avuto un grande impatto sul mio lavoro. Ora ho accesso a molte più fotografie di quante ne potrei mai guardare. Così come chiunque altro. Sotto molti aspetti le cose sono diventate molto facili. Cerchi qualcosa, accendi il motore, ed eccolo lì, in tutta la sua diversità. Desideri il fiore blu, ne ottieni migliaia in un batter d’occhio. E questo è tanto noioso quanto sembra. Quando esploro siti come Flickr di solito non cerco niente di specifico, ma studio il flusso di upload in arrivo, e occasionalmente scopro qualcosa che cattura la mia attenzione. So cosa cerco solo quando lo vedo.

SB/MZ: Rispetto a Baldessari, Hans-Peter Feldmann e Boltansky tu come hai diretto il materiale trovato?

JS: Non paragonerò il mio lavoro a quello di altri artisti. Questo è il lavoro degli storici dell’arte. Gli uccelli non fanno il lavoro degli ornitologi.

photo credit D. Lasagni

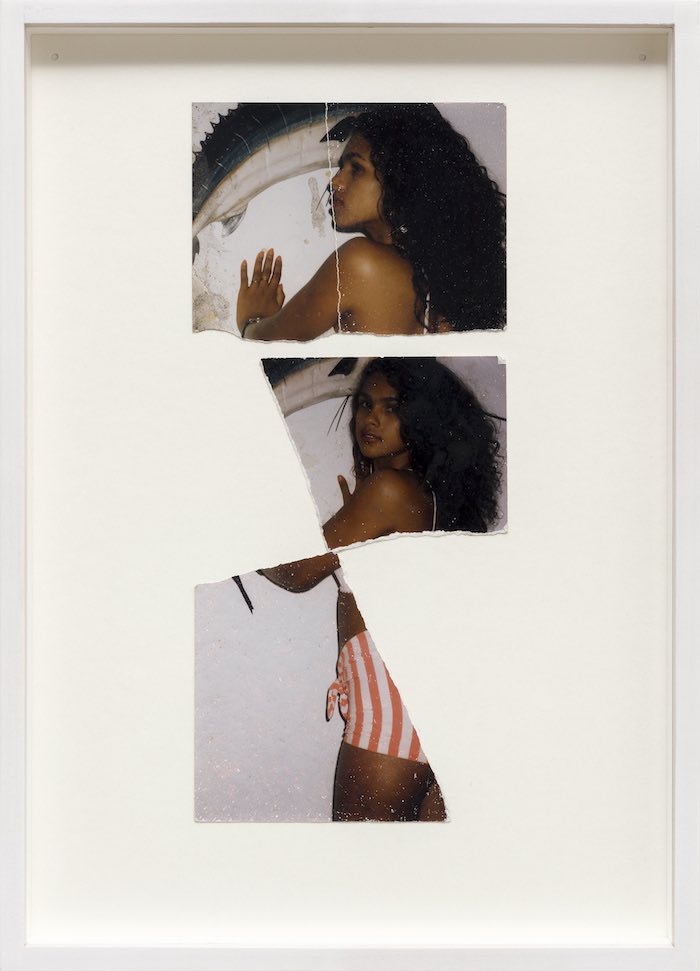

photo credit C. Favero

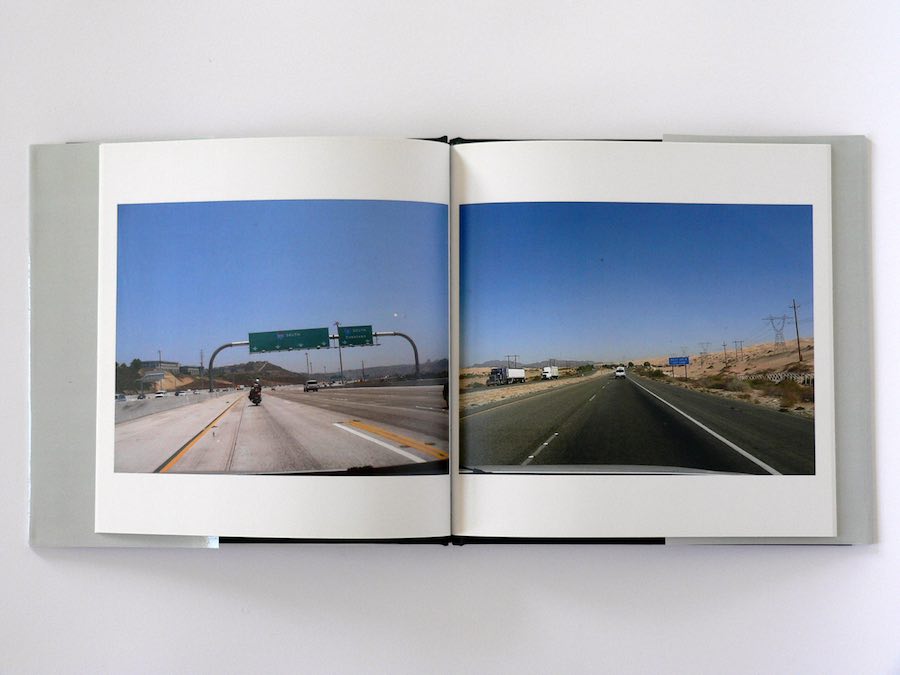

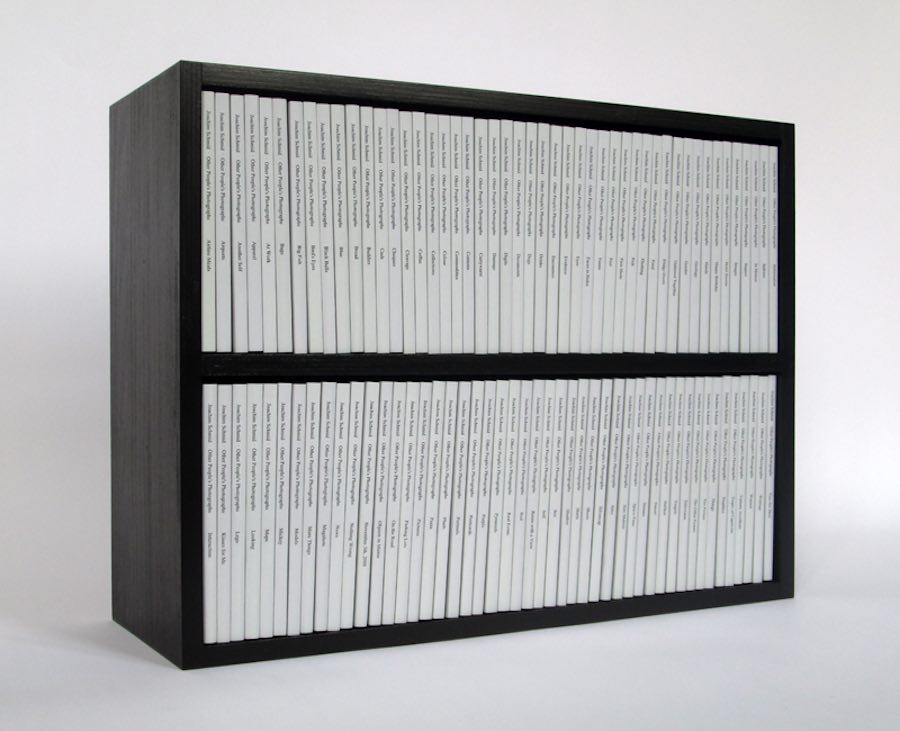

SB/MZ: Dopo aver esplorato Flickr con i 96 volumi del progetto Other People’s Photographs, dove hai diretto la tua attenzione?

JS: Compilare questi 96 volumi è stato uno sforzo enorme. Ci sono voluti più di tre anni e in quel periodo ho guardato Flickr per dodici ore al giorno, a volte anche di più. Dopo un po’ ho iniziato a sentirmi come un drogato che è inorridito dalla sua stessa dipendenza. Guardare le foto degli altri per così tanto tempo non fa bene al proprio benessere mentale. Quando ho iniziato il progetto ho avuto un’idea, ma nessun piano. Ma dopo un po’ di tempo è diventato chiaro che ad un certo punto tutto questo doveva finire. Quando il progetto è stato completato non ho guardato nessun sito web di foto per un bel po’ di tempo. Invece sono tornato a guardare di nuovo il mio ambiente fisico, comprese le visite occasionali ai mercatini delle pulci. Il risultato sono opere come Estrelas amadas o The Artist’s Model. Anche queste si basano su immagini trovate, ma su foto di natura industriale, che sono state personalizzate in vari modi dai loro precedenti proprietari. Mi piace come le fotografie vengono usate e modificate dalle persone, come vengono modellate secondo i desideri e le ossessioni di qualcuno. Probabilmente è ancora più interessante delle istantanee che la gente si fa da sola.

SB/MZ: Oggi esci ancora di casa in cerca di spunti concreti o affidandoti al fattore caso, all’incontro fortuito in un mercatino delle pulci? Se sí, cosa comporta per un artista ripartire da qualcosa che aveva sondato molti anni prima, avendo fatto anche esperienza dell’innumerabile materiale della rete?

JS: Il caso gioca un ruolo cruciale. Come ho detto prima, c’è sempre un’idea di quello che potrei voler fare, ma non un vero e proprio piano. Sono sempre stato aperto agli incontri casuali, molte delle mie opere reagiscono a qualcosa che trovo o a una situazione in cui mi trovo. Quando si rivede una situazione dopo qualche anno, quella situazione non è più la stessa, e nemmeno io sono più lo stesso di prima.

SB/MZ: Le foto finiscono nei mercatini delle pulci prevalentemente solo dopo la morte dei protagonisti. Cosa significa per te lavorare con ciò che è venuto a mancare, con la sparizione, con la traccia di momenti di vita di qualcuno che ora non c’è più? Come ti proietti rispetto a tutte le storie degli altri che sono giunte a te?

JS: Quando lavoravo con le istantanee dei mercatini delle pulci negli anni ’80 e ’90, c’erano due problemi principali: in primo luogo, era disponibile solo un numero relativamente piccolo di foto, ma per identificare i modelli ne avevo bisogno di molti; in secondo luogo, dato che le fotografie di solito vengono vendute in questi mercatini solo dopo la morte di una persona, ero sempre una o due generazioni indietro rispetto ai miei tempi. Per questi motivi sono stato felice di dire addio ai mercati delle pulci quando i siti di hosting fotografico online sono diventati una valida alternativa. Sia quando lavoravo con i mercatini delle pulci che con le foto online ho sempre cercato di mantenere il mio lavoro impersonale. Il lavoro non riguarda le persone raffigurate e nemmeno le persone che hanno realizzato le foto, ma le immagini. Non riguarda nemmeno me stesso, anche se le persone che studiano il lavoro possono giungere a conclusioni su di me. Va bene, ma non ho un ruolo molto attivo in questo processo.

Non farsi coinvolgere nella vita di un estraneo può essere difficile quando hai tutte le foto di quella persona sulla tua scrivania. A volte si impara molto su quella persona, e spesso non è proprio quello che si voleva sapere. Per evitare di farmi coinvolgere troppo in modo indesiderato ho scattato delle foto fuori contesto, ignorando ogni informazione biografica, concentrandomi rigorosamente sull’unico aspetto che mi interessava all’epoca. I capelli di qualsiasi storico probabilmente si drizzerebbero se osservassero il mio metodo di lavoro.

SB/MZ: Nelle tue ricerche come ti esponi al mondo? Ricordi qualche momento estatico o di rivelazione particolare quando hai trovato fotografie o immagini, che probabilmente in quel determinato momento del tuo percorso era necessario incontrare?

JS: Cammino per il mondo con gli occhi spalancati e cerco di rimanere aperto, pronto a raccogliere tutto ciò che può essere utile lungo il cammino. Naturalmente ci sono stati momenti di serendipità, incontri, scoperte – senza di essi si è perduti se non si ha un piano. La maggior parte della mia arte ha avuto origine da un tale momento di serendipità. È l’inizio perfetto, il resto è lavoro.

SB/MZ: Quali strategie hai messo in atto dopo la compulsiva osservazione delle foto altrui per liberarti dai flussi di immagini di persone che usavano Flickr e dalla inevitabile dipendenza?

JS: Una disintossicatione a freddo. Non c’è più la routine quotidiana di accendere il computer al mattino e di spegnerlo la sera. Non ho visitato alcun sito di foto per mesi. Andare a fare passeggiate, liberare la mente, riorientare la mia attenzione, leggere, andare al cinema.

photo credit C. Favero

photo credit C. Favero

photo credit C. Favero

SB/MZ: La maggior parte delle persone riproduce sempre (sia nell’epoca analogica sia in quella digitale e probabilmente in quella delle macchine quantiche) certe immagini di sé stessa, sia per quanto riguarda la sfera intima sia per quanto concerne il suo ruolo nel mondo. Avviene la stessa proiezione anche quando si raccoglie un materiale che proviene da altri?

JS: Immagino che sia un pericolo serio. Ci sono preferenze, abitudini, modelli di percezione. Cerco di esserne consapevole il più possibile. Aiuta il fatto che mi faccio guidare dal materiale a disposizione e non da un piano preconcetto.

SB/MZ: Ha mai preso in considerazione o lavorato sulla questione delle immagini scattate per capriccio momentaneo (ovviamente nell’ottica degli scatti realizzati a raffica con i cellulari) e che non vengono guardate da nessuno, le fotografie di cui ci si scorda dopo cinque minuti o di quelle che vengono memorizzate da qualche parte e non vengono più guardate? Ci può parlare del nuovo che continua a seppellire il già scattato con innumerevoli altri scatti dimenticabili?

JS: Temo che questo sia vero per la maggior parte delle foto fatte oggi. Considerando il numero di foto che la gente sforna, è piuttosto sicuro presumere che molte di esse vengano guardate una volta sola e mai più. Alcune vengono condivise sui social media, sostituite da quella successiva in pochissimo tempo, scorrono lungo la linea del tempo e scompaiono nell’abisso. Studiando Flickr e siti simili mi sono imbattuto in racconti con sei, sette, otto cifre di foto, la maggior parte delle quali non contrassegnate, identificate solo dal numero di file attribuito dalla fotocamera. È quasi impossibile ritrovarle, impossibile ricordarle tutte, ed è improbabile che qualcuno le cerchi. Spesso mi chiedo perché qualcuno si preoccupi di caricarle. Sembra un processo automatico, caricare l’intero lotto della giornata, svuotare la memoria della fotocamera o del telefono, fare spazio per il lotto successivo, andare avanti. E francamente, la stragrande maggioranza di essi sono totalmente e assolutamente privi di interesse se non si è stati alla festa dove sono state fatte le foto; fatte per il momento, guardate una volta, spinte sullo sfondo dalla serie successiva, dimenticate. Ci sono anche moltissimi racconti abbandonati. Le persone fanno e condividono le foto per un po’ di tempo, si interessano ad altre cose, vanno avanti, non fanno più il login, ma le loro foto sono lì finché il server non si rompe o l’host non scompare.

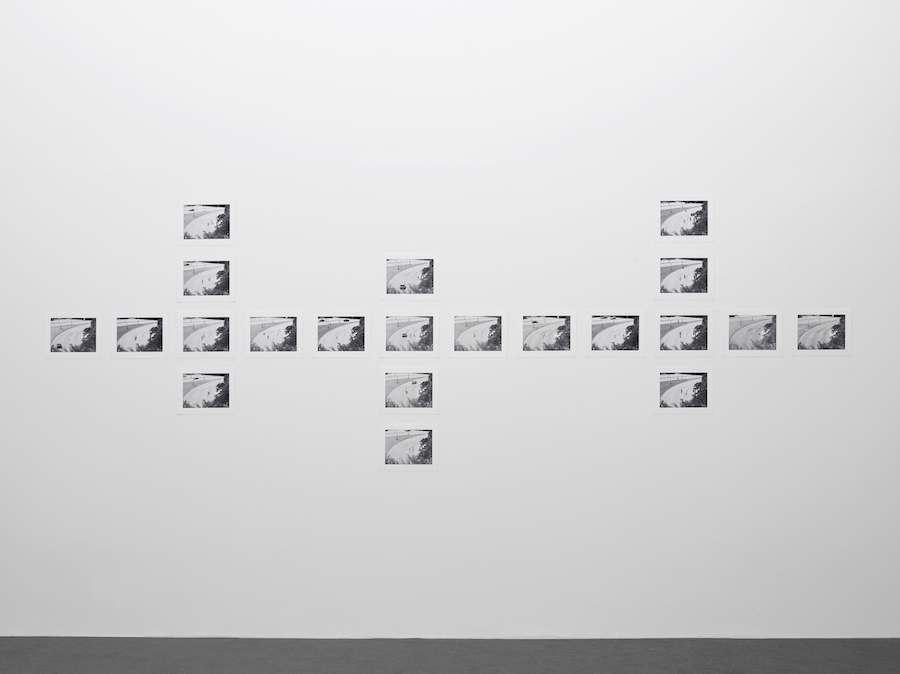

SB/MZ: Ci interessa molto il tuo progetto X Marks the Spot, che riguarda la Dealey Plaza di Dallas, dove fu assassinato Kennedy, dove le foto mostrano persone che se ne stanno in mezzo alla strada, proprio nel punto in cui avvenne l’omicidio, ripresi anche da una webcam che trasmette le riprese della strada. Quale è il rapporto tra guardare e essere guardati, nel rapporto tra libertà d’azione e controllo dall’alto?

JS: Questo è uno dei prodotti collaterali di Other People’s Photographs. Guardando il flusso costante di upload senza particolare enfasi mi sono imbattuto in foto di persone in piedi accanto a una X dipinta sul marciapiede di una strada. È stato facile scoprire cosa stava succedendo, e strano vedere che la gente lo faceva. Ho iniziato a raccogliere queste foto. Non sono riuscite ad entrare nel grande progetto. Più tardi ho fatto qualche ricerca intorno a questo fenomeno e ho scoperto la webcam posizionata esattamente nel punto in cui si trovava l’assassino. La prospettiva della videocamera corrisponde a quella della pistola. Ho iniziato a guardare i filmati della webcam per mesi e ho scattato fotogrammi ogni volta che ho visto persone fotografare sul posto. È un cerchio chiuso, la webcam registra le persone che scattano foto e alcune di queste foto vengono poi condivise sui social media. Entrambe sono accessibili istantaneamente a qualcuno a migliaia di chilometri di distanza. Ho visto la gente che veniva osservata. La libertà non mi è venuta in mente in questo contesto, tranne forse la libertà di trasformare tutto in un business. La webcam è gestita da un museo che è un’impresa commerciale come al solito negli Stati Uniti, e la X è dipinta sul marciapiede da venditori ambulanti di souvenir, attirando clienti che rischiano la vita per un’istantanea che non è stata una loro idea.

SB/MZ: Quale è il tuo rapporto tra prima idea e costruzione di un progetto attraverso il libro?

JS: All’inizio trovo qualcosa, spesso devo cercarne di più, e quando penso che ci sia materiale sufficiente inizio a lavorare senza sapere cosa sarà, un libro, un lavoro da appendere, o qualsiasi altra cosa. Lavorare significa cercare e cercare di nuovo finché non penso di aver capito quello che guardo. Poi seleziono e sistemo le parti fino a quando la combinazione appena creata funziona. Ad un certo punto di questo processo diventa chiaro quale sia la forma più adatta al materiale in questione.

Interview with Joachim Schmid

By Sara Benaglia and Mauro Zanchi

SB/MZ: 40 years after you started working on found photography, what are the most interesting drifts that can be made today by your intuition and this kind of look? How can you go beyond the current mainstream trend of those who work from found photography?

JS: My work is an ongoing research of visual culture with a particular focus on non-professional photography. That’s a vast field and surprisingly there’s still unmapped territory. Whether or not part of it is “interesting” I only know after stepping into it. Of course I am not the only one working in this field, and some works based on found photography may now be compatible with the art world’s mainstream. I do the work I wish to do; neither becoming part of the mainstream nor distancing myself from it plays any role in my mind.

SB/MZ: Which has been the evolution of this practice?

JS: The evolution of my work was and is subject to the same factors that characterize evolution in its Darwinian sense. It’s an erratic, volatile random process rather than a development following any logic. Maybe you could call it continuous discontinuity. The only progress is that I try to limit repetition, in particular avoiding mistakes I made before.

SB/MZ: How has the approach changed through the Internet tap, search engines and the flood of images?

JS: The flood of images isn’t a new phenomenon, you can trace the topic back at least a century. But the numbers have exploded of course after digital photography became a popular pastime. The amalgamation of phone and camera was the final boost. Now photographs are the constant background noise of every human activity. The really crucial thing however is not the number of photographs that are being made but the fact that many of them are public now. A generation ago the majority of photographs were in private, corporate, or governmental archives with very limited access for a limited number of people only. Now an ever-growing number of images are accessible for virtually everybody. Online photo hosting created an utterly new visual environment. And the search engine makes it manageable, at least to a certain extent. However, the search is based on verbal input; many photos are uploaded without any captions or descriptions and for this reason they are not included in the search results. Thus online photo hosting sites turned into tremendous digital landfills of visual trash.

All of this has had a big impact on my work. I have access now to many more photographs than I could possibly ever look at. So does everybody else. In many respects things have become very easy. You are looking for something, you start the engine, and there it is, in all its diversity. You wish for the blue flower, you get thousands of them in no time. And that’s as boring as it sounds. When I explore sites like Flickr I usually don’t look for anything specific but I study the incoming stream of uploads, and occasionally I discover something that catches my attention. I only know what I look for when I see it.

SB/MZ: Compared to Baldessari, Hans-Peter Feldmann and Boltanski how did you direct the found material?

JS: I won’t compare my work to the work of other artists. That’s the job of art historians. Birds don’t do the work of ornithologists.

SB/MZ: After exploring Flickr with the 96 volumes of the Other People’s Photographs project, where did you direct your attention?

JS: Compiling these 96 volumes was an enormous effort. It took more than three years and in that time I looked at Flickr for up to twelve hours a day, sometimes probably even more. After a while I started feeling like a junkie who’s appalled by his own addiction. Looking at other people’s photos for such a long time is not good for your mental well-being. When I started the project I did have an idea but no plan. But it became clear after some time that this had to stop at some point. When the project was completed I didn’t look at any photo websites for quite a while. Instead I went back to looking more at my physical environment again, including occasional visits to flea markets. The result are works like Estrelas amadas or The Artist’s Model. These are also based on found imagery, but on photos of an industrial nature that were personalized in various ways by their previous owners. I like how photographs are being used and altered by people, how they are shaped according to someone’s wishes and obsessions. That’s probably even more interesting than the snapshots people make themselves.

SB/MZ: Are you still going out of the house today in search of concrete ideas or relying on the chance factor, the chance encounter at a flea market? If yes, what does it mean for an artist to start again from something he had probed many years before, having also experienced the innumerable material of the net?

JS: Chance does play a crucial role. As I mentioned before, there’s always an idea what I may want to do but not really a plan. I have always been open to chance encounters, many of my works react to something I find or to a situation I find myself in. When re-visiting a situation after some years that situation isn’t the same any more, and I’m not the same I was before either.

SB/MZ: The photos end up in flea markets mainly after the death of their protagonists. What does it mean for you to work with what has disappeared, with the loss, with the trace of moments in someone’s life that is now gone? How do you project yourself in all the stories of others that have come to you?

JS: When working with snapshots from flea markets in the 1980s and 90s there were two main problems: first, only a relatively small number of photos were available but for identifying patterns I needed many; second, because of the fact that photographs usually are sold at these markets only after a person’s death I was always one or two generations behind my own time. For these reasons I was happy to say good-bye to flea markets when online photo hosting sites became a viable alternative.

Both when working with flea market and with online photos I always tried to keep it impersonal. The work is not about the persons depicted and not about the persons who made the pictures but it’s about the pictures. It isn’t about myself either although people who study the work may come to conclusions about me. That’s ok but I don’t play a very active role in this process.

Not getting involved in a stranger’s life can be difficult when you have all the photos of that person on your desk. Sometimes you learn quite a lot about that person, and it’s often not exactly what you wanted to know. To avoid getting too much involved in an unwanted way I took photos out of context, ignoring any biographical information, strictly concentrating on the one aspect I was interested in at the time. Any historian’s hair would probably stand on end if they watched my work in progress.

SB/MZ: In your research, how do you expose yourself to the world? Do you remember any particular ecstatic or revealing moment when you found photographs or images, which you probably needed to meet at that exact moment of your journey?

JS: I walk through the world with open eyes and try to remain open-minded, ready to pick up whatever may be useful along the way. Of course there were serendipitous moments, encounters, findings – without them you are lost if you don’t have a plan. Most of my art originated from such a moment of serendipity. It’s the perfect start, the rest is work.

SB/MZ: What strategies did you put in place after compulsive observation of other people’s photos to free yourself from the streams of images of people using Flickr and the inevitable addiction?

JS: Cold turkey. No daily routine any more of switching on the computer in the morning and switching off at night. I didn’t visit any photo sites for months. Go for walks, free the mind, re-direct my attention, read, go to the movies.

SB/MZ: Most people always reproduce (both in the analogue and digital age and probably in the quantum machine age) certain images of themselves, both in the intimate sphere and regarding their role in the world. Does the same projection also occur when one collects material that comes from others?

JS: I guess that’s a serious danger. There are preferences, habits, patterns of perception. I try to be aware of them as far as possible. It helps that I am guided by the material at hand and not by a pre-conceived plan.

SB/MZ: Have you ever considered or worked on the question of images taken on a momentary whim (obviously with a view to the snapshots taken with mobile phones) and that are not looked at by anyone, photographs that are forgotten after five minutes or those that are stored somewhere and are not looked at anymore? Can you tell us about the new one that keeps burying the already taken with countless other forgettable shots?

JS: I’m afraid that’s true for the majority of photos made today. Considering the number of photos people churn out it is rather safe to assume that many of them are looked at once and never again. Some are shared on social media, replaced by the next one in no time, they move down the timeline and disappear in the abyss. Studying Flickr and similar sites I came across accounts with six, seven, eight figure numbers of photos, most of them untagged, identified only by the file number attributed by the camera. It’s nearly impossible to find them again, impossible to remember all of them, and unlikely that anyone will ever look for them. Often I wonder why anyone would even care to upload them. It seems to be an automatic process, upload the entire batch of the day, empty the camera’s or the phone’s memory, make space for the next batch, move on. And frankly, the vast majority of them are totally and utterly uninteresting if you were not at the party where the photos were made; made for the moment, looked at once, pushed to the background by the next series, forgotten. There are also lots of abandoned accounts. People do make and share photos for a while, they get interested in other things, they move on, never log in again, but their photos are there until the server breaks down or the host disappears.

SB/MZ: We are very interested in your project X Marks the Spot, which is about Dealey Plaza in Dallas, where Kennedy was assassinated. In this project the photos show people standing in the middle of the street, right at the spot where the murder took place, also filmed by a webcam that transmits footage of the street. What is the relationship between watching and being watched, in the relationship between freedom of action and control from above?

JS: That’s one of the collateral products of Other People’s Photographs. Looking at the constant stream of uploads without any particular emphasis I came across photos of persons standing by an X painted on the pavement of a street. It was easy to find out what was going on, and strange to see that people did it. I started gathering these photos. They didn’t make it into the big project. Later I did some research around this phenomenon and discovered the webcam placed exactly at the location where the assassin stood. The camera’s perspective matches that of the gun. I started watching the webcam’s footage for months and grabbed frames whenever I saw people taking photographs at the spot. It’s a closed circle, the webcam records people taking photos and some of these photos are later shared on social media. Both are accessible instantly to someone thousands of miles away. I watched people being watched. Freedom is not something that came to my mind in this context, except maybe the freedom of turning everything into a business. The webcam is operated by a museum which is a commercial enterprise as usual in the US, and the X is painted on the pavement by souvenir hawkers, attracting clients who risk their lives for a snapshot that wasn’t their idea.

SB/MZ: What is your relationship between a first idea and the building of a project through the book?

JS: In the beginning I find something, often I have to look for more, and when I think there’s sufficient material I start to work without knowing what it’s going to be, a book, a work for the wall, or whatever. Work means looking and looking again until I think I understand what I look at. Then select and arrange the parts until the newly created combination works. At some point in this process it becomes clear what the most suitable form for the respective material is.

Per leggere le altre interviste della rubrica NEW PHOTOGRAPHY