Can you feel your own voice è il claim della 52esima edizione di Santarcangelo Festival. Un monito che assume forme artistiche ed estetiche differenti, ma che si pone sempre come pratica culturale e politica.

Nel lavoro di Maria Magdalena Kozlowska la voce è elemento sociale e semantico, strumento di espressione del sé e della relazione con l’altro. È a partire da questa considerazione, e da una formazione musicale e teatrale, che l’artista di origine polacca ha realizzato COMMUNE (in scena dal 9/07)una vera e propria opera teatrale che vuole reclamare i corpi delle donne nel genere. Uno spettacolo che rovescia i canoni storici, musicali, teatrali e narrativi, in un atto di celebrazione del corpo e della voce. In programma il primo weekend del Festival al Teatro Amintore Galli di Rimini, COMMUNE porta sul palco con seria ironia le proteste per i diritti fondamentali delle donne, il fantasma di una nonna comunista, Rosa Luxemburg e la performatività della musica.

Maria Magdalena Kozlowska ci ha raccontato il suo rapporto con l’opera e la musica dal quale nasce la sua ricerca artistica e che ha dato vita ad un’opera frenetica, onirica e ironica come COMMUNE.

Guendalina Piselli: Let’s start with an easy question. What is COMMUNE and what will the public see on the stage during the performance?

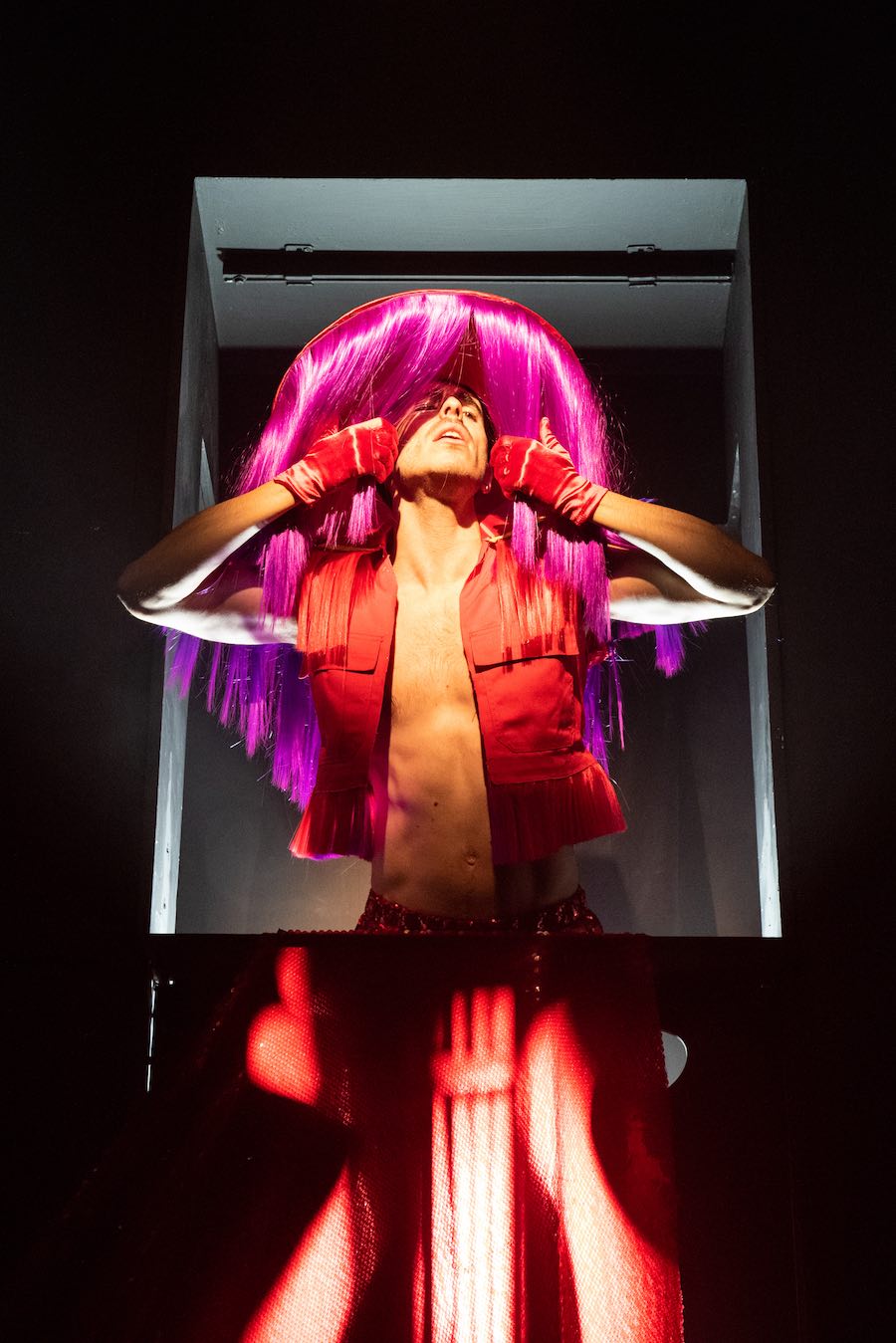

Maria Magdalena Kozlowska: The dictionary definition of a commune is “a group of people who live together, sharing belongings and responsibilities”. My COMMUNE is an attempt to reclaim women’s bodies in opera, foregrounding their unruly physiology and gaze. The work depicts an episode from the life of a gang of masked female musicians. They feel the urge to express their rage, but lack the knowledge about protesting. They decide to summon the Communist Grandma. She shows them how to channel their anger through opera. The Grandma, portrayed by the outstanding male soprano Maayan Licht, is based on my own granny. With a pinch of Rosa Luxemburg. The rest of the characters are played by classically trained musicians – flutists Teresa Costa and Beatrice Miniaci, as well as a percussionist Aleksandra Wtorek. Together, we experimented with ways to expand the instrumentalist’s performativity. Instead of traditional stillness, we added a lot of movement, which does not equal resignation from virtuosity. On the contrary – the passion for music becomes more embodied that way. We are looking for body-positive, emancipatory opera. Women are not suffering here – they celebrate their unruly bodily fluids and vocalize their complex feelings.

GP: This is not the first that your work with opera – I am thinking about Opera to the People. What makes this kind of music so interesting to you?

MMK: I’ve always seen opera as an aestheticised scream. I believe it has a great potential in terms of “redistributing the sensible”, changing the angle from which we experience power structures of our society. The operatic voice is loud, direct and in that sense marks the very idea of being heard. Actually, one has no choice but to hear it. It’s like a siren, like an alarm, a powerful sound wave, which carries a potential to bring attention to something. I started working with it through “operatic videos”, outside of the theatrical context. My roots are in visual art, jazz and experimental music. In my earlier work I was interested in celebrating the soundscape of everyday life. For example, I always admired the acoustics of a staircase in a typical soviet block of flats. The reverb can be as spectacular there, as the one in a cathedral. And so I made Alcina//Ah mix cor, a short video about a heart broken girl in an Adidas jumpsuit. The video was exhibited by the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw and later in Kronika Contemporary Art Centre in Bytom, which was great, but at the same time I found myself more and more attracted by music theatre. I graduated from a theatre school in Amsterdam right in the middle of the pandemic. Along with Pankaj Tiwari, an artist-curator, we were looking for ways to continue working. Opera to the People came as an answer to that need. Singing from a boat guaranteed a safe distance. It allowed me to continue investigating the acoustics of urban landscapes. In that case, the encounter between the voice and bodies of water in a city. We performed the piece in Zurich, Berlin and Amsterdam.

We were curious to see how public space and operatic spectacle can inform each other. Opera to the People was an invitation to renegotiate the terms of spectatorship and participation. On one hand, the spectacle was forced on passers-by. On the other, it was in constant motion, so it was impossible to witness the whole piece. It remained elusive, capricious and always fragmented. There were no tickets or assigned seats, but there was also no climax.

GP: In COMMUNE piece, music and politics seem pretty linked. How can working on music make a difference on today’s society?

MMK: Music has the power of building instant, powerful relations. It helps us work through our collective emotions, allows us to gather around it. We rub our bodies against other bodies, while dancing to it. It strikes people so directly, it doesn’t need language to communicate. However, we often use musical vocabulary to speak of communication – “it resonates with me”, “I feel I’m not heard.” The voice, my field of musical expertise, has both social and somatic properties – it comes from the body and it can influence other bodies. Within the language, it becomes the metaphor of itself. For example, we say “to raise one voice” or “speak up” – the expression indicates a literal, physical action, but also refers to a gesture of making oneself part of a conversation, especially for a right cause. The voice marks self-expression and identity, since it is so unique. It also helps us to accept a certain obscenity and otherness within ourselves. The voice comes from us, but it also immediately leaves our body and becomes part of the public domain – reverberates in a certain way, reacts to the acoustics. It becomes uncanny. I think that through experiencing this mystery of our own voice, we can become more aware of our role in the broader context – a group, a society, the environment.

GP: In occasion of Santarcangelo COMMUNE will be performed at Teatro Amintore Galli in Rimini so a traditional space to go for opera….

MMK: I’m extremely excited about the opportunity to occupy the building for a moment. The traditional aesthetics creates a beautiful undertone for COMMUNE, which, after all, is still a contemporary music piece. At the same time, we are very willing to re-think the aesthetics of an opera house. Jan Tomza’s water sculptures, as well as the costumes he designed, come from a dark, post-punk sensitivity. It’s both bombastic and unsettling. Let’s see what kind of an aesthetic dispute will emerge from the juxtaposition of those two visual worlds. We are interested in questioning the division between the audience and the untouchable, holy space of the stage. I would gladly bring the audience to the stage and create a space for them to cultivate their polyphony. Maybe that’s an idea for a new project.

GP: Sounds like a piece full of humor…

MMK: Operatic voice has a lot to do with an outburst of laughter – it is a life force, exploding from the body and striking everybody in its range. I use comedy in many of my works, because of its community-building potential. Laughter is a very serious, deeply political tool. To laugh is to subvert power, it’s to give a testimony of passion and energy. Authoritarian forces often find it threatening, as it brings a promise of emancipation from fear. Comedy usually bases on unexpected juxtapositions, it is born from the entanglement of pathos and the vernacular, the solemn and the banal, the philosophical and the stupid. On the level of form, COMMUNE alludes to opera buffa, operatic comedy, which historically arose as a genre for “common people”. It often told stories of everyday life, instead of praising Gods or tragic lovers. We are creating a meta-operatic journey, cracking jokes about opera itself. We oppose deadly seriousness, which can make an art form dead as well. I believe that opera, within its extravagance and eccentricity, can be exciting and radical.

GP: In your work you deal with the main and most urgent issues of the society such as the role of women and their rights. However, these themes are not explicitly exposed on the stage. There is always a kind of shift both from reality and collective imagination…

MMK: I practice poetic social critique, which engages collective imagination and invites it to join an introspective adventure. I work with distortion, interference and displacement. I believe that an accurate and acute juxtaposition is more likely to be a catalyst of transformation than a moralistic effort. In my work, the political tropes are often disguised as fiction, very often in a story of an “I”, which does not necessarily represent me. But having a narrator and her supposedly singular story, allows me to convey political messages in a more discrete way. This is also how an advertisement, or sophisticated propaganda works – it makes certain values effortlessly attractive. You want to adopt them, because you fall in love with the reality built in front of you.

GP: One last, and maybe uncomfortable, question. Feel free to not reply to this one. How much the situation in Poland (your country of origin) influences your artistic research?

MMK: It is customary for a Polish artist to denigrate their country, to complain about it and publicly mock it. I think only Austrians have a similarly dark and twisted sense of national identity. I enjoy that self-irony very much. I don’t trust patriots. The ambivalence, intrinsic to any identity, certainly informs my work. It fuels the humor and dialectic thinking. However, Poland is like a toxic, yet clever mother – it holds a firm grip over you by inspiring pity and worry for her. And so I’m obviously very concerned about the fascist government and infuriated by the despicable laws it implements against women and the LGBTQ+ community. They also managed to take control over a lot of important institutions of art, which makes it hard for me to imagine moving back there, even though I love working in Poland. I see some hope in the impotence and clumsiness of the party in power. They resemble those unlucky cartoonish characters, who try hard, plot all the time, but somehow always end up in a pit. On the other hand, maybe that’s what actually makes them easy to identify with and fuels their popularity? Anyway, I feel very connected to Polish playful sensitivity and I don’t think it will ever disappear from my work.

Maria Magdalena Kozlowska

COMMUNE

Sabato 9 luglio h. 21.30

Domenica 10 luglio h. 20

Teatro Amintore Galli, Rimini