[nemus_slider id=”66231″]

Segue il testo in italiano

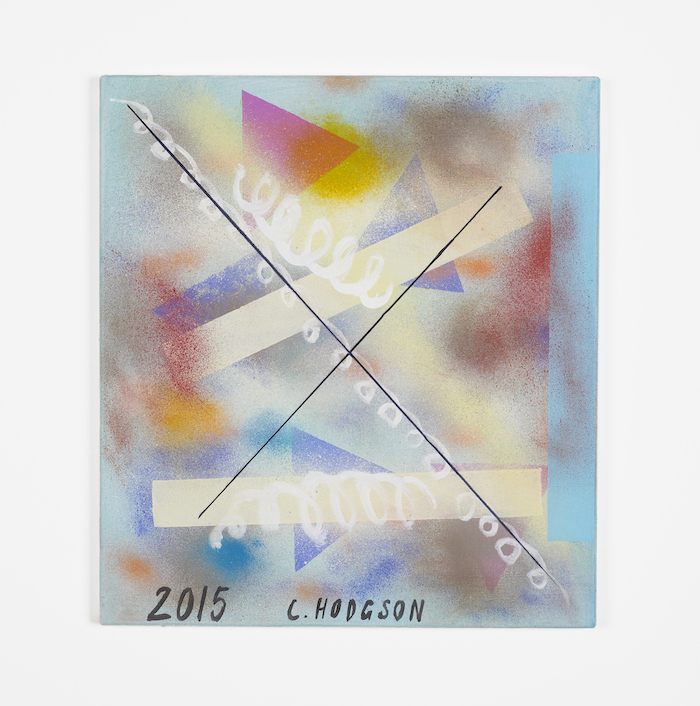

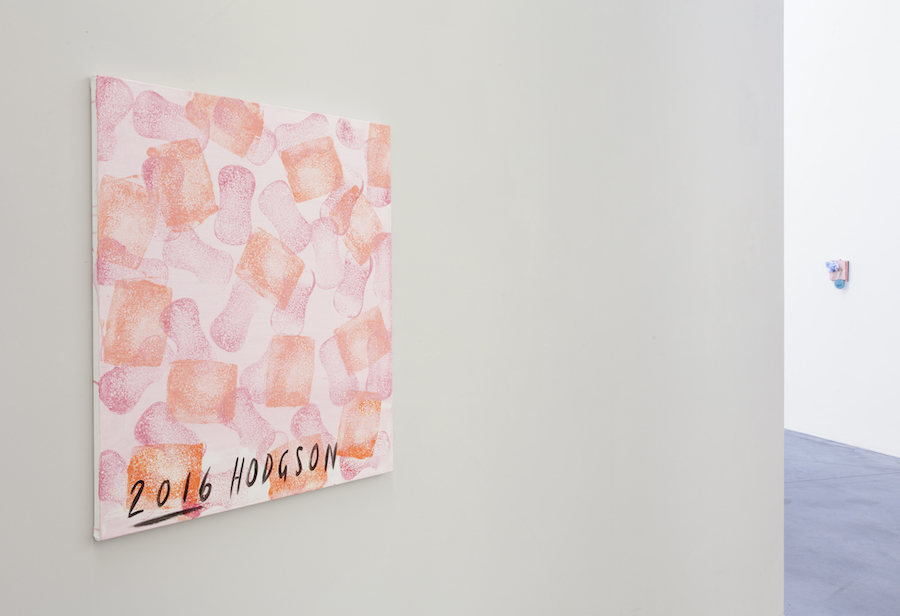

British artist Clive Hodgson started as an abstract painter, switched to figuration, then turned back to abstraction; now he makes paintings within which he takes up ideas about painting itself. Giulia Ponzano interviews him about his work, which will be on view during GRANPALAZZO 2017 (May 27th and 28th), the exhibition-fair organised at Palazzo Chigi of Ariccia in Rome.

ATP: Can you say something about the structures, motifs, patterns and general ‘content’ in your works? Are these irregular and simple structures seeking freedom from limitations and formulae? Is there a relation between the abstraction and things seen in the world?

Clive Hodgson: The ‘imagery’, if that is what it is, is derived largely from what is, historically speaking, the relatively recent and continuing tradition of abstract painting, but also from all sorts of decorative painting and painted patterns and effects that one sees way back in history. I love Roman painting for example, for its pleasure in pattern, decoration and depiction and for its anarchic interlacing of these aspects. I take notice of things in the world but there is no direct intended correspondence between things in these paintings and specific things I see, such as my cat.

ATP: All your works are ‘Untitled’; unpredictable, apparently meaningless things, which refuse any form of narration and lack gravity and weight – can these be read also as gesture of political negation and act of refusal, counter reaction of the heavy socio-political situation we are going through?

CH: I do prefer the idea of lightness to weight. The problem with meanings and narrative is that they give the painting a clear job to do, which I don’t like. This may be a refusal on my part, as you say, but the impulse is constructive and involves a kind of ludic juggling of elements whose status and relationships are very variable. If all of this is forced into a kind of instrumentalism and reason, there is a loss. The latitude, the freedom, the uncertainty, is important.

ATP: Can your paintings be considered self-portraits or more as windows to the world?

CH: I think of painting more as its own rather introverted world, which offers me a degree of freedom and pleasure. The pleasure (and pain, depression, anxiety, etc.!) lies in exploring and manifesting what seems valuable in this painted world. I don’t assume that this has relevance for somebody else. The trail of paintings left behind may be some sort of indication of a ‘self’ but it’s a self I’m happy not to know too well.

ATP: Your works seemingly invoke a dry and charming British humour – How directly has the visual experience of the place you live in affected your work? Have you always been based in London?

CH: I try to see a lot of art, and I value and appreciate the public collections of art in London. The availability of so much art (mostly free!) is very important to me, and also a pleasure. I like almost everything about the city except the pollution and cars – it is time to change that. The contemporary art scene has grown enormously during my time here (ages) and I am glad it is here, though my instinct is to be suspicious of and dislike almost everything. I work on this problem of suspicion and dislike and I am seeking a long-term cure.

ATP: Your signature is always accompanied by another pictorial element, the year – a rational, precise and consistent value in contrast with the other shapes, grids, lines and strokes floating in the canvas. Is the presence of time a statement or, instead, the subversion of its own meaning?

CH: I guess it is right that the repetition of certain elements, such as name and date, gives a sense of an ongoing process, with the implication of a past and a future? and a relation between the separate paintings. The name and date are (very conventional) elements in the painting: as you say, pictorial elements. Are they pictorial? I don’t know, they seem to be both part of the painting and also not part of it, but they are certainly painted letters and numbers. Numbers and letters exist in the paintings in a way that they don’t in a diary for example, where the numbers are printed. The significance of this is not clear to me. I am aware of time passing – I am running out of it. If I can subvert its meaning, I will.

Intervista con Clive Hodgson

In occasione della sua partecipazione a GRANPALAZZO (27-28 maggio 2017, Villa Chigi, Ariccia), con la galleria Arcade, Giulia Ponzano ha posto alcune domande all’artista.

ATP: Puoi dirmi qualcosa sulle strutture, sui motivi, sui pattern e sul contenuto generale che caratterizzano i tuoi lavori? Queste strutture semplici e irregolari cercano in qualche modo libertà da limitazioni e formule prescritte? C’è una relazione tra la tua astrazione e le forme/oggetti che popolano il mondo?

Clive Hodgson: L’immaginario, se così si può definire, deriva in gran parte da una tradizione storica relativamente recente e continuativa della pittura astratta, ma anche da tutti i tipi di pittura decorativa, ovvero motivi ed effetti che si ritrovano nella storia passata. Per esempio, amo la pittura romana, per la sua passione per pattern, decorazioni e rappresentazioni e per l’intrecciarsi anarchico di questi aspetti. Prendo nota delle cose nel mondo che mi circondano, ma non esiste alcuna corrispondenza diretta tra le forme dipinte e le cose specifiche che vedo, come il mio gatto.

ATP: Tutte le tue opere sono ‘Senza titolo‘; forme imprevedibili e apparentemente insignificanti, che rifiutano ogni tipo di narrazione e sembrano non disporre di alcuna gravità e peso – queste forme possono essere interpretate anche come gesto di negazione politica e di atto di rifiuto, contro-reazione alla grave situazione socio-politica che stiamo attraversando?

CH: Preferisco l’idea di leggerezza a quella di pesantezza. Il problema con il significato e la narrazione è che affidano alla pittura un lavoro da fare, il quale non mi piace. Questo può essere considerato, come dici tu, un rifiuto da parte mia, ma l’impulso è costruttivo e coinvolge una sorta di manipolazione di questi elementi che hanno status e relazioni molto variabili. Se tutto questo è portato a piegarsi a una sorta di strumentalismo e ragione, abbiamo una perdita. La libertà d’azione e l’incertezza sono importanti.

ATP: Le tue opere possono essere considerate autoritratti o più come finestre che si affacciano sul mondo?

CH: Penso alla pittura più come a un mondo a sè stante piuttosto introverso, che mi offre una certa libertà e piacere. Il piacere (e il dolore, la depressione, l’ansia, e così via) risiede nell’esplorare e manifestare ciò che sembra prezioso in questo mondo dipinto. Questo potrebbe non aver rilevanza per qualcun altro. Il percorso dei dipinti lasciati indietro potrebbe essere una sorta di indicazione di un ‘sé’, però si tratta di un sé che sono felice di non conoscere troppo bene.

ATP: Le tue opere sembrano richiamare un umore britannico, freddo e affascinante – Come l’esperienza visiva del luogo in cui vivi ha direttamente influenzato i tuoi lavori? Hai sempre vissuto a Londra?

CH: Cerco di vedere molta arte e apprezzo le collezioni pubbliche a Londra. La disponibilità di tante mostre ed eventi artistici (per lo più gratis!) è molto importante per me ed è anche un piacere. Mi piace quasi tutto della città, tranne l’inquinamento e le auto – è il momento di cambiare tutto ciò. Lo scenario dell’arte contemporanea è cresciuto enormemente durante il mio periodo a Londra (parlo d’anni) e sono contento di essere qui, sebbene il mio istinto sia quello di essere sospettoso e di non mi piace quasi nulla di quello che vedo. Sto lavorando su questo mio problema di diffidenza, cercando una cura a lungo termine.

ATP: La tua firma è sempre accompagnata da un altro elemento pittorico, l’anno – un valore razionale, preciso e coerente in contrasto con le altre forme, griglie, linee e pennellate che caratterizzano la tela. La presenza del tempo è una dichiarazione o piuttosto la sovversione del suo significato?

CH: Immagino sia giusto che la ripetizione di alcuni elementi, come il nome e la data, dia un senso di un processo in corso, con l’implicazione di un passato e di un futuro? E anche una relazione tra diversi dipinti. Il nome e la data sono elementi (molto convenzionali) del dipinto: come hai definito, elementi pittorici. Sono pittorici? Non lo so, sembrano essere entrambi parte del dipinto pur non facendone parte, ma sono certamente lettere e numeri dipinti. Numeri e lettere esistono nei dipinti in un modo che non si trova, per esempio, in un diario, dove i numeri vengono stampati. Il significato di questi ultimi non mi è chiaro. Sono consapevole dello scorrere del tempo – lo sto esaurendo. Se posso sovvertire il suo significato, lo farò.