[nemus_slider id=”72754″]

—

Italian text below

We meet the Czech artist Eva Kot’àtkovà (Prague, 1982) to share a few words about her upcoming exhibition at Pirelli HangarBicocca “The Dream Machine is Asleep” (February 15 – July 22); we spoke about her new work presented here, about subliminal influences and children’s dreams.

ATP Diary: The exhibition at Pirelli HangarBicocca is called “The Dream Machine is Asleep”, could you please explain us the title? What new work will we see?

Eva Kot’àtkovà: “The Dream Machine is Asleep” is based on the conception of the body as a machine, machine constituted of smaller machines that we carry within us. And then there are perhaps bigger machines around us that influence us, those small machines within us. These bigger machines can be rules of institutions for example that tell us how to behave, that send the body various impulses or orders. The exhibition continues my interest in exploring the relation between the inner forces and external impulses and how these cooperate or get into conflict with each other. This is the general theme but then there is the concrete work that gave the whole exhibition its title: the large 10 metres long bed which is being occupied by both adults and children.…..

The installation The Dream Machine is Asleep centres around a hypothetical idea: what would happen if the dream machine would fall asleep, decide to take a break or simply stop functioning from various reasons. And since the fact is that while growing older we loose subsequently the ability to dream (or at least the length of a dream gets shorter and shorter) I decided to call children to help to provide dreams to those who are not able to dream anymore. Children became necessary protagonists, suppliers of dreams, collaborators that made the exhibition complete. Physically but also conceptually the installation of the bed is divided into 3 parts or zones: On the ground floor there is an office for the children where they write down and record their dreams and visions, on the upper level the visitors can lay down on the bed and listen to the audio created by the children and in an enlarged drawer of the bed one can find arrested bad dreams, dark visions, phobias and anxieties, that are kept, at least temporarily away, from attacking our heads.

ATP: The Shed at Pirelli HangarBicocca is a peculiar exhibition space, how and to what extent have you been influenced by it?

EK: It is the largest space I have had the chance to work in and with so far. In general I prefer spaces that are less clean and neutral, the Shed was therefore an ideal space for the materials with which it is built, the floor that carries the memory of the previous shows, the roughness, the metal structures. “The Dream Machine is Asleep” thus naturally fitted to this kind of space – one could think perhaps the Shed was a dream factory before. In the same time it took me some time to get used to the large scale and adapt my works to it as what was important for me was to turn the large space into an intimate one, a kind of night landscape in which one discovers disturbing elements but in the same time still wants to travel further.

ATP: Your work deals often with slumber, dream and infancy, what are the subconscious influences you might have had while producing your works? Or that in general shapes your artistic practice?

EK: I have always been interested in stories and in the images that we create in our head while listening to them. And then in the images we construct or recall while dreaming and how are these shaped by what we experience in everyday reality. The main answer for the questions arising around this particular exhibition at Pirelli HangarBicocca is that the “machine” actually never sleeps and perhaps it is even more vivid when we sleep. The body is only seemingly passive as the head processes what has happened the day or days before. I have worked with ideas and visions of other people in the past, for example in a series of works that dealt with ideas of psychiatric patients. There it was not so much linked to dreams but rather to imagining as a parallel reality, drawing worlds that one inhabits in his or her head. In other cases I collaborated with groups of seniors and children who would exchange stories and borrow each other biography. I am also very much interested in children drawings or in outputs of those who do not consider themselves as artists, people without artistic training and who create records of their mind processes out of inner necessity and obsession.

ATP: Fences, cages and walls stand for the normative measure in social contexts that surveil, control and constraint movements and also thoughts, in your opinion how can art help to overcome them?

EK: At least within exhibition spaces art can overcome such constraints and forces by proposing new hierarchies, schemes or models of how the world could function. Sometimes just the turn to communication through images rather then through words can be quite freeing. Even thought I include a lot of text in my works I also aim to create strong visual images or experiences (choreographing the way one walks through the space, encounters things within it, test some of them physically etc)that could approach the viewer directly, addressing or perhaps even trying to awaken hidden, sleeping or suppressed images and thoughts within us. Ideally a sort of unlearning of the body would happen when experiencing the exhibition. And naturally the themes I touch on are those that I consider to be problematic-lacking ability of empathy, our relation to other creatures, situation of those who do not have a voice and are labeled as handicapped from various reasons. The dream machine can thus hopefully not only provide dark documents of the present, but can also propose scenarios for a better future.

Eva Kot’átková — The Dream Machine is Asleep

Pirelli HangarBicocca ospita “The Dream Machine is Asleep”, dal 15 febbraio al 22 luglio 2018, la mostra personale di Eva Kot’átková, concepita come un percorso di immagini e parole, un mondo labirintico e surreale che invita a produrre sogni e a sviluppare l’immaginazione, mettendo in luce le fantasie individuali, le paure e le sfide della società contemporanea.

A cura di Roberta Tenconi

Al centro di “The Dream Machine is Asleep” è l’omonima installazione, un gigantesco letto alla cui base è presente quello che l’artista definisce un ufficio per la creazione di sogni. Con questo lavoro Eva Kot’átková prosegue la sua ricerca sui sistemi che regolano la nostra vita, contrapponendo loro immagini provenienti dall’universo infantile per supplire alla mancanza o alla perdita di immaginazione. Immaginate che le persone non siano più in grado di sognare – recita l’invito dell’artista nel cercare i giovani collaboratori per creare un archivio di sogni a disposizione dei visitatori della mostra milanese. Non solo durante la notte, ma anche durante il giorno alle persone manca l’immaginazione. Questo è il vostro compito in questo lavoro: fornire sogni e idee a tutti quelli che passano la notte senza sonno e senza sogni o quelli che vivono monotone giornate lavorative con rigidi orari e prive di eventi inaspettati. Diventate ingegneri (costruttori) dei sogni degli altri, diventate fornitori di sogni.

Per accedere allo spazio espositivo i visitatori sono invitati ad attraversare l’opera Stomach of the World (2017), un’allegoria del mondo, descritto come un organismo caotico che alterna processi di assimilazione famelica, a momenti di stasi, di empatia o di scontro tra i suoi abitanti, a fasi di controllo, digestione, espulsione e riciclo delle “scorie” prodotte, ovvero le fobie e gli stati d’ansia. L’opera, composta da un video presentato all’interno di un’installazione percorribile dai visitatori e che assume la forma del disegno stilizzato di uno stomaco, si avvale di protagonisti e immagini presi dal mondo dell’infanzia e della mitologia.

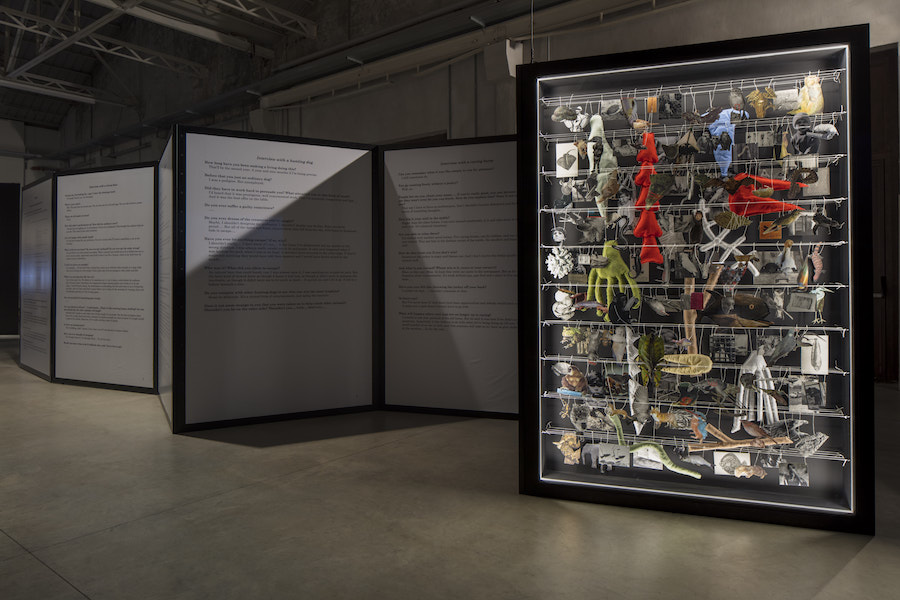

Nello spazio dello Shed di Pirelli HangarBicocca numerosi oggetti fuori scala punteggiano l’intera mostra, mettendo il pubblico a confronto con un immaginario a cavallo tra letteratura fantastica e scienze neurologiche. Accanto a una serie di sette enormi teste in metallo (Heads, 2018) che vengono regolarmente attivate e completate dalla presenza immobile di performer e che rappresentano maschere in cui trovare riparo, i visitatori possono sfogliare le pagine di libri che raggiungono i due metri di altezza. Questi libri (Diaries, 2018) raccolgono piccole sculture e collage – una tecnica largamente adottata nel Surrealismo e molto amata da Eva Kot’átková per la sua intrinseca natura in cui si uniscono frammenti ed elementi differenti in nuove composizioni – e rappresentato un diario in cui vengono raccolti pensieri attorno alle disfunzioni e alle peculiarità del mondo contemporaneo.

In The Theatre of Speaking Objects (2012), invece, undici oggetti quotidiani e di arredamento come un vaso, una porta o un muro, assumono caratteristiche antropomorfe, facendosi portavoce di traumi nascosti. L’opera è stata presentata alla 18° Biennale di Sydney ed è ispirata a una serie di schizzi dell’architetto ceco Jiri Kroha (1893-1974), che negli anni ’20 aveva immaginato una piece teatrale utilizzando semplici utensili quotidiani a cui dava voce e caratteristiche umane. Nella cacofonia di voci, che parlano idiomi differenti, e nell’utilizzo di oggetti come surrogato del corpo umano, Eva Kot’átková mette in luce le situazioni in cui non è possibile esprimersi liberamente dando invece la possibilità di farlo attraverso questa comunicazione indiretta, usando gli oggetti come mediatori.

L’intera mostra viene concepita come un organismo che, attraverso performance programmate, si anima e viene abitato da figure che si aggirano nello spazio attivando le opere con semplici azioni statiche, con coreografie più complesse o attraverso narrazioni orali estemporanee. Così in Asking the Hair about Scissors (2018), un anomalo e surreale parrucchiere, i visitatori possono ricevere racconti liberamente composti da Eva Kot’átková a partire da fatti di cronaca: chiedendo di rinunciare a una parte del proprio corpo, i capelli, l’artista ripropone l’idea di frammentazione. (Comunicato stampa)