English version below

MAST Photography Grant on Industry and Work premia talenti emergenti della fotografia, con un’attenzione particolare rivolta al tema del lavoro. L’edizione 2023 del premio si concentra sulla rapida e incessante trasformazione che contraddistingue il mondo del lavoro in società globalizzate e in continua connessione: il progetto vincitore è In Praise of Slowness di Hicham Gardaf, un vero e proprio inno alla lentezza che emerge sullo sfondo di una Tangeri dalla duplice anima, antica e moderna. Hicham Gardaf ha deciso di raccontarsi, rispondendo ad alcune domande sul suo progetto e sulla sua pratica artistica.

Veronica Pillon: In Praise of Slowness è il progetto vincitore dell’edizione 2023 di MAST Photography Grant on Industry and Work: ci descriveresti il lavoro e il concept alla base?

Hicham Gardaf: In Praise of Slowness riflette sulla natura dei lavori che stanno scomparendo – nel caso specifico i venditori ambulanti di candeggina – e in che modo detengano il potere di distruggere e rigettare i modelli dominanti di consumo in seguito alla modernizzazione di Tangeri. L’idea di realizzare questo progetto è stata suscitata dalla voce di un venditore ambulante di candeggina, mentre ero in visita a Tangeri qualche anno fa. Inizialmente la mia idea era di creare un’installazione sonora immersiva, ma quando sono stato nominato per il MAST Photography Grant ho dovuto ripensarne lo sviluppo e adottare un nuovo formato. Sono riuscito a mantenere l’elemento sonoro anche nel lavoro finale, incorporandolo nel film. All’interno dell’opera c’è una sorta di gioco di specchi: le fotografie presentano la stessa scena da diverse prospettive. La striscia gialla dipinta sulla parete della galleria è ripetuta negli scatti e nel film. Quest’idea si ricollega alla memoria: quando si vede qualcosa, questo riporta alla mente altro che si pensa di ricordare dal proprio passato.

VP: Il tuo lavoro spazia tra fotografia, film e installazione: come li utilizzi?

HG: Me ne servo come strumenti per raccontare storie, suscitare idee e impegnare lo spettatore in una conversazione critica con il contesto circostante. Contestualmente li utilizzo come strumenti per perseguire la mia ricerca.

VP: In Praise of Slowness un uomo cammina portando sulle spalle delle bottiglie vuote: intorno a lui un paesaggio desolato. Nei tuoi lavori, qual è la relazione tra uomo e natura?

HG: Nei lavori precedenti, mi focalizzavo sugli spazi in cui c’era una congiunzione tra spazio urbano e naturale. In particolare, l’incontro, il confine tra la presenza umana e la natura e che impatto ha sul paesaggio. Ora il focus del mio lavoro si è spostato verso la riflessione sull’aspetto industrializzato della presenza umana. Percepisco come la presenza dell’essere umano sia, sfortunatamente, connessa all’erosione del mondo naturale. Questa relazione è assolutamente sbilanciata verso l’essere umano, che detiene il potere. Paradossalmente, a discapito del dominio dell’essere umano, la distruzione dell’ambiente ha conseguenze soprattutto su chi si trova in una posizione di fragilità e vive in condizioni precarie. Il paesaggio alle spalle dell’uomo che sta camminando è desolato ma nello stesso tempo industrializzato, uno di quegli spazi che sono stati pesantemente trasformarti e sottomessi alla presenza dell’essere umano, per massimizzare l’efficienza e raggiungere il profitto.

VP: Il progetto è ambientato in una moderna Tangeri. Che cosa rappresenta per te la città? Ci sono dei registi in particolare che rappresentano per te un modello e che hanno influenzato il modo in cui rappresenti il paesaggio?

HG: Tangeri è la mia città natale. È il luogo in cui sono nato e cresciuto. È il luogo dei miei ricordi d’infanzia e in cui è nato il mio interesse per la fotografia, il cinema e la letteratura. È anche un’incredibile fonte d’ispirazione. Sono molti i modelli che mi hanno ispirato (Agnès Varda, Andrei Tarkovsky, Ingmar Bergman e Robert Bresson) ma ce n’è solo uno che ha avuto una diretta influenza sul mio ultimo progetto ed è Michelangelo Antonioni. Il suo primo film a colori, Il deserto rosso, è eccezionale dal punto di vista visivo e sonoro. Un film che ha superato la prova del tempo. La palette di colori, la cinematografia, l’uso della musica elettronica e di suoni industriali sono elementi di grande forza del film.

VP: La settima edizione del premio si concentra sui cambiamenti del mondo del lavoro, che si succedono rapidamente nella nostra società globalizzata e capitalista. Paradossalmente, il tuo lavoro si concentra sulla lentezza e sulle tradizioni locali: perché hai scelto di concentrarti su questo aspetto?

HG: Negli ultimi anni, sento che è in corso un cambiamento nel carattere della nostra società. Una trasformazione in relazione alla nostra percezione ed esperienza del tempo. Sebbene il tempo rimanga costante, ho la percezione crescente che si restringa, che ciascuna delle persone che conosco si trovi in una corsa, alla ricerca di qualcosa che non può raggiungere. L’espressione “tempo libero” è sostituita dall’assioma “Il Tempo è Denaro”. Lo sviluppo della tecnologia ha un impatto sul modo in cui comunichiamo, consumiamo e lavoriamo. Oggi si può lavorare in qualsiasi luogo e tempo, tanto che i confini che una volta separavano la vita professionale da quella privata sono sempre più sfocati, se non eliminati. Desideravo il tempo in cui chi conosco era tranquillo, disponibile, presente, sereno. Forse ciò che mi ha spinto a concentrarmi sulle tradizioni è stata , in prima battuta, proprio la capacità di rallentare il tempo, di cambiare il processo del consumo così come dettato dal capitalismo, “che esige che ogni desiderio venga soddisfatto immediatamente” per dirla con le parole di bell hooks. Quando i venditori ambulanti stanno vendendo ciò che hanno prodotto, il consumatore non può predire il giorno e il momento in cui passeranno. L’atto di aspettare il passaggio dell’ambulante permette ad un lasso di tempo in cui uno non fa nulla di esistere. Questa azione risulta radicale, urgente e vale la pena celebrarla.

Interview with Hicham Gardaf — MAST Photography Grant on Industry and Work 2023

In Praise of Slowness by Hicham Gardaf (Tangier, 1989), winner of the seventh edition of the Grant, is a tribute to slowness: the core theme is represented by the contrast between the prosperous, flourishing and expanding part of the city and the historic center with its ancient charm, the fresh shadow at the base of the walls that mark its perimeter, the slow and reflective pace of people and street vendors.

Veronica Pillon: In Praise of Slowness is the winning project of “MAST Photography Grant on Industry and Work” 2023: would you like to describe your artwork to us and explain its concept?

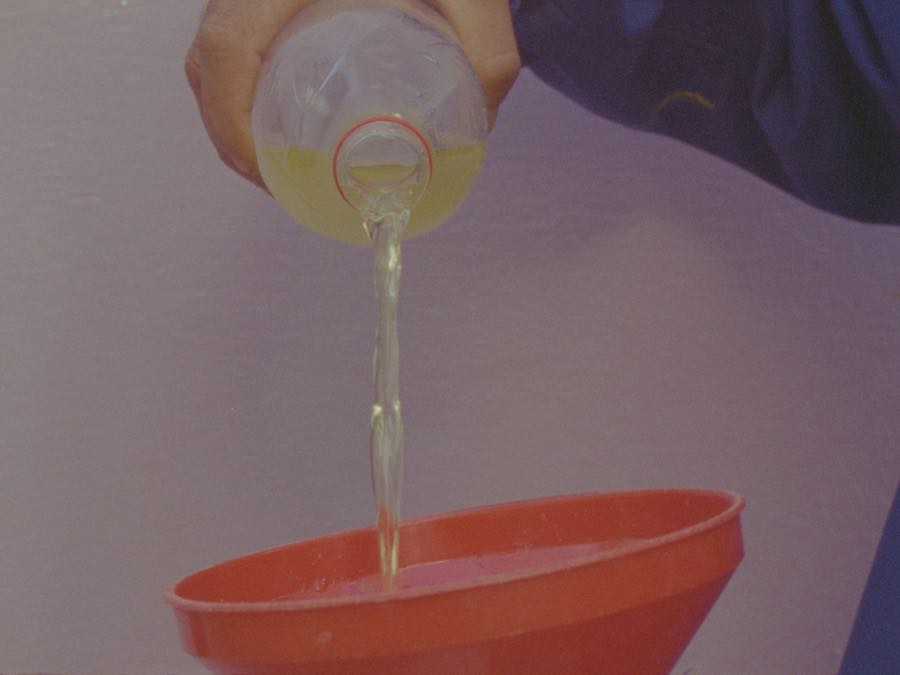

Hicham Gardaf: In Praise of Slowness meditates on the nature of vanishing jobs — in particular the bleach street sellers — and how these still hold the power to disrupt and reject the ruling modes of consumption in the wake of Tangier’s modernisation. The idea to make this project was triggered by the sound of a bleach vendor while I was visiting Tangier a few years ago. At first, my idea was to create an immersive sound piece, but when I was nominated for the MAST Photography Grant I had to rethink the outcome and came up with a new format. I was still able to maintain the sound element in the final work by incorporating it into the film. Within the work there is a sense of mirroring—photographs present the same scene from different perspectives: the yellow stripe painted on the wall of the gallery is repeated in the photographs and in the film. This idea is connected with work of memory: you see something and it reminds you of something else that you think you remember from your past.

VP: You work across photography, film and installation: how do you use them?

HG: I use them as tools to tell stories, conceive ideas and engage the viewers in a critical conversation with their immediate environment. But I also use them as a tool to conduct my own research.

VP: In In Praise of Slowness a man walks carrying empty plastic bottles on his shoulders: around him a desolate landscape. What is the relationship between human and nature in your works?

HG: In my previous works I was interested in spaces that are at the intersection/meeting point of urban and natural worlds. The meeting, the border of human presence and environment and how it affects the natural landscape but the focus of my current work has shifted into thinking of the industrial aspect of human presence. I feel like human presence is unfortunately connected with the erasure of the natural world. This relationship is definitely unbalanced, to the advantage of humans in terms of control. Yet, paradoxically, despite all the human dominance, the disruption of nature impacts many of those who are in a vulnerable position and live in precarious conditions. The landscape that is setting the background for the walking man is desolate but also industrial, one that has been heavily transformed and subdued by humans to serve efficiency and profit.

VP: This artwork is set in a modern Tangier: what does the city mean to you? Are you inspired by any filmmaker in the way you capture the landscape thought the Camera?

HG: Tangier is my hometown. I was born and raised there. It is the place where my childhood memories are housed and where my curiosity for photography, literature and cinema was born. It is also an incredible source of inspiration to me. There are many filmmakers that I am inspired by (Agnès Varda, Andrei Tarkovsky, Ingmar Bergman and Robert Bresson, to name only a few), but if there is one filmmaker that had a direct influence on my recent film, then Michelangelo Antonioni would be the one. His first colour film Red Desert was visually and sonically remarkable. A film that stood the test of time. The colour palette, the cinematography, the use of electronic music and industrial noise are all very strong elements of the film.

VP: The seventh edition of the grant is focused on the changes of the world of work, which occur rapidly in our globalized and capitalist society. As a paradox, your work reflects about slowness and vernacular traditions: why did you decide to focus on them?

HG: In recent years, I feel that there is a behavioural change taking place in our society. A shift in relation to our perception and experience of time. Although time remains constant, I have an increasing sensation that it is shrinking, that everyone else I know is in a rush, looking after something they cannot reach. The word leisure is being replaced by the axiom Time Is Money. The advance of technology impacted the way we communicate with each other, consume and work. It is now possible to work almost from anywhere, thus the boundaries that once separated the personal from the professional life are now blurred (or erased). I was longing for the times in which everyone I knew seemed to be dawdling, available, present, and in peace. Perhaps what made me focus on these vernacular traditions in the first place was their ability to slow down time, to challenge the consumption process as found in a capitalist model— one “that demands all desire must be satisfied immediately”, to use bell hooks words. When the pedlars are selling their produce, the consumer can’t predict the day and time in which they will pass by. The act of waiting for the street sellers to pass by allows for a time frame — in which one does nothing— to exist. This act felt radical, urgent and worth celebrating.

MAST Photography Grant on Industry and Work

Mostra collettiva a cura di Urs Stahel

Fondazione MAST

Via Speranza n. 42, 40133 Bologna

Fino al 1° maggio 2023