English version below

Dopo l’introduzione e le interviste alla direttrice dello Schermo dell’Arte Silvia Lucchesi, al curatore della sezione VISIO Leonardo Bigazzi e al direttore di Palazzo Strozzi Arturo Galansino, Martina Odorici è l’autrice di alcune brevi interviste a registi e artisti partecipanti al festival: Antje Ehmann, collaboratrice e moglie di Harun Farocki, che presenterà Parallel I – IV (2014) e a Lisa Immordino Vreeland, regista statunitense, che presenterà il biopic Peggy Guggenheim: Art Addict (2015).

Venerdi 20 novembre, dalle ore 21 presso il Cinema Odeon, Antje Ehmann, in conversazione con Erika Balsom, introdurrà Parallel I – IV (2014), uno degli ultimi lavori di Harun Farocki, cui è dedicato quest’anno il Focus On del festival. Il regista tedesco, da poco scomparso, è stato protagonista, dagli anni ’60 a oggi, di un grande cinema di critica; critica dell’immagine e delle costruzioni che attraverso di essa vengono create, critica della storia, della politica, della società e della violenza. Cinema forte, eversivo e potente, il suo, che negli ultimi tempi si è concentrato sui cambiamenti che la tecnologia ha portato in tutti i campi della vita umana, dall’intrattenimento alla guerra. Di questa ultima serie di lavori ci parla direttamente Antje Ehmann, collaboratrice e moglie di Harun Farocki.

ATP: Harun Farocki è stato un maestro della critica dell’immagine. Qual’è il punto di vista dei suoi ultimi lavori?

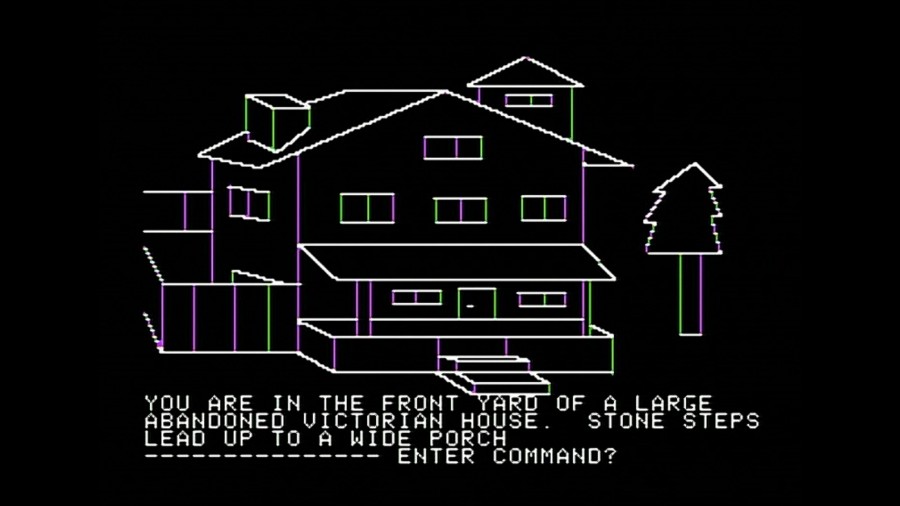

Antje Ehmann: Parallel I – IV esplora la storia visuale dei videogiochi e analizza come queste immagini animate sono usate nell’industria dell’intrattenimento e della grafica digitale. In soli 30 anni le immagini e le animazioni generate dai computer si sono sviluppate dalle linee pixelate degli anni ’80 ai videogame iperrealistici di oggi. Harun Farocki si è accostato a questi mondi virtuali non tanto come un giocatore o un sociologo, ma piuttosto dalla prospettiva di un teorico dei media o di uno storico dell’arte. Parallel è un’analisi della cultura visiva contemporanea. E indaga lo spostamento dalla rappresentazione (film) alla costruzione (realtà virtuale). Il cinema è sempre stato un legame indessicale al reale, grazie alla potenzialità del film di registrare tracce di realtà fisica e preservarle come immagini durevoli. La domanda è: cosa succede quando immagini di videogame generate da un computer – immagini che non possiedono il legame indessicale di cui parlavamo – surclassano il film in quanto medium predominante della creazione visiva del mondo? Come si modifica la relazione con il mondo se non ci identifichiamo più come corpi reali ma come avatar senza emozioni?

ATP: In Parallel I – IV ha seguito l’evoluzione della grafica computerizzata, che è vista anche come un modo insospettato e insospettabile per trasmettere e illustrare la violenza. In che modo?

AE: Parallel investiga le limitazioni e i confini di paesaggi animati così come le restrizioni del movimento corporeo e i comportamenti sociali dei personaggi. La domanda sul perché questi mondi sono così violenti e aggressivi è presente, ma non direttamente espressa. Ma c’è un commento che ci può dire qualcosa di più: “Gli eroi qui non hanno genitori o maestri; devono trovare da soli le regole da seguire. Raramente hanno più di una espressione facciale e decisamente pochi tratti caratteristici, che vengono espressi attraverso una limitata serie di brevi frasi. Sono homuncoli, esseri antropomorfi, creati dall’uomo. Chiunque giochi con loro spartisce con il creatore un po’ d’orgoglio creativo.”

ATP: Il cinema di oggi è molto influenzato dalla virtualità e dalla tecnologia. Quali sono state le influenze per Farocki?

AE: Harun Farocki è sempre stato interessato alla politica delle immagini, al modo in cui le immagini, le tecnologie e i sistemi di rappresentazione definiscono e controllano lo spazio politico e sociale. La maggior parte dei suoi ultimi lavori si concentra sull’interfaccia tra uomo e macchina, e specialmente sul mondo delle macchine che hanno volto umano, come si può osservare nella serie di installazioni Eye/Machine I-III (2000-2003) o nel film War at a Distance (2003).

ATP: Harun Farocki è sempre stato molto critico verso la politica, la storia, la violenza e le pratiche di oppressione nascoste dietro le immagini sul grande schermo, come abbiamo detto. Crede che questi punti siano importanti anche per i giovani artisti e registi di oggi?

AE: La teorica cinematografica Nicole Brenez conclude un testo su Harun Farocki1 con il seguente aneddoto: “Qual’è il film più politicamente attivo, il film più sovversivo della storia del cinema?”. A questa domanda che Brenez pose in Cahiers di Cinéma a diversi filmmaker e storici, il giovane regista argentino Mauro Andrizzi, regista dell’esemplare Iraqi Short Films (2008), rispose: “Videograms of a Revolution, di Harun Farocki e Andrei Ujica (1992).”

1 Nicole Brenez, “Harun Farocki and the Romantic Genesis of the Principle of Visual Critique, ” in Antje Ehmann and Kodwo Eshun, Harun Farocki. Against What? Against Whom? Cologne 2009, pp. 128-142, qui p. 142.

Sabato 21 novembre, alle ore 21.45 presso il Cinema Odeon, sarà presentato per la prima volta in Italia Peggy Guggenheim: Art Addict (2015), alla presenza della regista Lisa Immordino Vreeland.

Dopo il documentario sulla fotografa di moda Diane Vreeland, del 2012, Lisa Immordino Vreeland ritorna a indagare sulla vita di una grande donna del XX secolo. La figura di Peggy Guggenheim, con la sua straordinaria intuizione, vitalità e forza, cattura l’attenzione della regista che, attraverso biografie, testimonianze, immagini e documenti d’archivio – e un’importante intervista inedita, l’ultima registrata da Peggy –, ricostruisce la sua vita affascinante e ricca, mostrando il suo retroterra culturale e l’ambiente e le persone brillanti di cui si circondava, artisti e addetti del mondo dell’arte. Uno sguardo complesso e aperto su una personalità altrettanto sfaccettata e interessante.

ATP: Perché ha deciso di dedicare un film a Peggy Guggenheim?

Lisa Immordino Vreeland: Il ruolo di Peggy nel mondo dell’arte è sempre più legittimato. Ci sono poche figure, nel mondo dell’arte, che hanno giocato un ruolo così centrale nelle vite degli artisti e in così tanti paesi; lei lo fece a Londra, Parigi, New York e Venezia. Era rivoluzionaria per quei tempi perché sceglieva le persone e le sottraeva all’oscurità, prima che fossero artisti famosi, e credeva in loro, e lo faceva nei suoi termini, senza seguire regole altrui. Penso che le sue storie personali, che sono tante, abbiano smorzato in qualche modo i suoi risultati. Con il senso di perdita che la circondava, avendo un sogno e una passione cui dava corso, niente poteva fermarla, ed essenzialmente fece tutto ciò che fece per il suo amore per l’arte.

ATP: Qual’è stato il suo approccio al soggetto, come si è sviluppata la struttura del film?

LIV: Questo è un lungometraggio in cui i materiali d’archivio giocano naturalmente un ruolo chiave nel racconto della storia. Abbiamo avuto l’opportunità di usare filmati di artisti e della loro arte per aiutarci a ricreare diversi periodi di tempo. Le conversazioni registrate tra Peggy e la sua biografa Jackie Weld hanno giocato un ruolo chiave e abbiamo cercato di creare la nostra storia attorno ad esse.

ATP: Nel film è inclusa anche l’ultima intervista di Peggy Guggenheim, che non era mai stata trasmessa o pubblicata. Questo “dettaglio” ha influito in qualche modo sul film?

LIV: Abbiamo comprato i diritti cinematografici di Peggy: The Wayward Guggenheim, l’unica biografia autorizzata di Peggy, pubblicata prima della sua morte, dalla sua autrice, Jacqueline Bogard Weld. Jackie aveva ottimi rapporti con lei, ha passato due intere estati a intervistare Peggy nel 1978-1979 e ha intervistato altre 200 persone, delle quali molte ora sono scomparse. Jackie è stata incredibilmente generosa, lasciandomi curiosare in tutte le sue ricerche originali, escludendo il fatto che non ricordava dove fossero I nastri delle conversazioni con Peggy. Un giorno le ho chiesto se avesse una cantina; ce l’aveva, e per caso ho trovato le registrazioni in una scatola di libri. Era la più lunga intervista che Peggy avesse mai concesso ed è diventata una cornice per il film. Non c’è niente di più potente della vera voce di una persona che racconta una storia, e Jackie era particolarmente brava a porre domande provocatorie. Se non avessimo trovato quella registrazione la storia sarebbe stata raccontata dalla voce fuori campo di un’attrice.

ATP: Qual’è “l’eredità” di questo film? Contiene qualche suggerimento ai collezionisti di oggi?

LIV: L’arte era il luogo dove Peggy aveva finalmente trovato se stessa. Quando Peggy decise di intraprendere quella carriera, questa diventò la sua passione la forza trainante della sua vita. Il suo desiderio di creare una collezione divenne la sua più grande motivazione. Si identificava con l’arte e gli artisti e trovava conforto in questo. E’ un impegno molto umano quello di dedicarsi all’arte ma lei aveva l’intuito per capirla, allo stesso tempo, e in ogni caso lo faceva per amore dell’arte e degli artisti.

LO SCHERMO DELL’ARTE – Interview with Antje Ehmann and Lisa Immordino Vreeland

From the 18th to the 22nd of November, 2015, Florence will host the eighth edition of Lo Schermo dell’Arte Film Festival. After the introduction and the interviews of the director of the festival Silvia Lucchesi, the curator of the section VISIO Leonardo Bigazzi and the director of Palazzo Strozzi Arturo Galansino, four brief interviews to some of the participating artists and directors.

Here the interviews with Antje Ehmann, collaborator and wife of Harun Farocki, that will present Parallel I – IV (2014), one of the last projects of the German artist, and with Lisa Immordino Vreeland, director of Peggy Guggenheim: Art Addict (2015).

Friday the 20th of November, from 9 pm at the Cinema Odeon, Antje Ehmann, with Erika Balsom, will introduce the public to Parallel I – IV, one of the last work of Harun Farocki, whom the Focus On of 2015 festival is dedicated. The German director, who passed away last summer, has been a prominent figure, from the 1960s until today, of what could be defined as the great cinema of consciousness and critics; critique of images and of the structures that thanks to it can be created, critique of history, politics, society and violence. A very powerful cinema, strong and subversive, that recently concentrated on the changes that technology engendered in every field of human life, from entertainment to war.

Of this last series of work we talk directly with Antje Ehmann, collaborator and wife of Harun Farocki.

ATP: Harun Farocki was a master in the critique of images. What is the point of view of these last works?

Parallel I – IV examines the visual history of computer games and how these animated images are used in the computer game and entertainment industry. In only 30 years, computer-generated images and animations have developed from the pixelated lines of the 1980s to the hyper-realistic videogames of today. HF approaches these virtual worlds not so much as a gamer or sociologist, but more from the perspective of a media theorist or art historian. The installation is an examination of contemporary visual culture. It questions the shift from representation (film) to construction (virtual reality). Cinema always had an indexical bond to the real, thanks to film’s ability to register traces of physical reality and preserve them as enduring images. The question is: what happens when computer-generated video game images – images possessing no such indexical bond – transcend film as the predominant medium of visual worldmaking? How does one’s relation shift when we no longer identify with real bodies, but with affectless avatars?

ATP: In Parallel I – IV he followed the evolution of computer graphics. This is also seen as an unsuspected means of conveying violence. In which way?

Parallel investigates the limitations and boundaries of animated landscapes as well as the restrictions of bodily movement and the social behavior of the characters. The question of why these worlds are so violent and aggressive is in the room but not directly addressed. We learn from the commentary: “The heroes have no parents or teachers; they must find the rules to follow of their own accord. They hardly have more than one facial expression and only very few character traits, which they express in a number of different short sentences. They are homunculi, anthropomorphic beings, created by humans. Whoever plays with them has a share in the creator’s pride.”

ATP: Nowadays cinema is very influenced by virtuality and technology. What were the influences for him?

HF was always interested in the politics of images, in the ways in which images, technologies and systems of representation define and control social and political space. Most of his late works concentrate on the interface of man and machine, and especially on the world of machines that have appropriated human sight, as you can see in his installation series Eye / Machine I-III (2000-2003) or in the film War at a Distance (2003).

ATP: Harun Farocki has always been very concerned with politics, history, violence and the practices of oppression hidden behind images on the screen. Do you think these are important points also for young directors and artists?

The film theorist Nicole Brenez ends a text about HF1 with the following anecdote: “What is the most activist, the most subversive film in the history of cinema?” To this question that [Brenez] posed in Cahiers du Cinéma to diverse filmmakers and historians, the young Argentinean filmmaker Mauro Andrizzi, director of the exemplary Iraqi Short Films (2008) replied: Videograms of a Revolution, by Harun Farocki and Andrei Ujica (1992).”

1 Nicole Brenez, “Harun Farocki and the Romantic Genesis of the Principle of Visual Critique, ” in Antje Ehmann and Kodwo Eshun, Harun Farocki. Against What? Against Whom? Cologne 2009, pp. 128-142, here p. 142.

Saturday the 21st of November, at 9.45 pm at the Cinema Odeon, will be presented, for the first time in Italy, Peggy Guggenheim: Art Addict (2015), in the presence of the director Lisa Immordino Vreeland.

After the documentary about the fashion photographer Diane Vreeland (2012), Lisa Immordino Vreeland investigates once again the life of a great woman of the XX century. The character of Peggy Guggenheim, so extraordinarily intuitive, strong and dynamic, grabbed the attention of the director, who, trough biographies, testimonies, archive documents, images and footage – and an important unpublished interview, the last one registered by Peggy before her death –, reconstructs her fascinating and rich life, unveiling her cultural background and the milieu of brilliant people of whom she surrounded herself, like artists and art world operators. A complex and open look on a likewise multifaceted and interesting personality.

ATP: Why did you decide to devote a film to Peggy Guggenheim?

LIV: As time goes on Peggy’s place in the art world is more legitimized. There are few figures in art history that played such a pivotal role in the lives of artists in so many countries; she did this in London, Paris, New York and Venice. She was revolutionary at that time because she was picking people out of obscurity, before they were known as successful artists and believed in them and she did it on her own terms. I think her personal stories, which are many, have diluted her real accomplishments. With the sense of loss that surrounded herself she had a dream and passion that she pursued, nothing stopped her, and ultimately she did it all for the love of art.

ATP: Which was your approach to the subject, how was the structure of the film built?

LIV: This was naturally a film where archival film was going to play a pivotal role in telling the story. We had the opportunity to use footage of artists and their art to help us recreate different periods of time. The taped conversation between Peggy and her biographer Jackie Weld were pivotal in the story and we tried to form our story around that.

ATP: In the film is included also the last interview held by Peggy Guggenheim, that had never been released. Was this “detail” central to the film?

LIV: We optioned Jacqueline Bogard Weld’s book, Peggy: The Wayward Guggenheim, the only authorized biography of Peggy, which was published after she died. Jackie had great access and spent two summers interviewing Peggy in 1978-1979 and spoke to 200 other people, many who now have passed away. Jackie was incredibly generous, letting me go through all her original research except she did not remember where the tapes of her conversation with Peggy were. One day I asked if she had a basement, and she did, eventually I found the tapes in a box of books. It was the longest interview Peggy had ever done and it became the framework for the film. There’s nothing more powerful than when you have someone’s real voice telling the story, and Jackie was especially good at asking provoking questions. If we had not found the times the narrative would have been based on a voice over by an actress.

ATP: Which is the “legacy” of this movie? Is there any suggestion to contemporary collectors?

LIV: Art was where Peggy Guggenheim finally found herself. When Peggy truly decided on this métier in her life it became her passion and her driving force. Her desire to build a collection became her biggest motivation. She identified with the art and the artists and found solace in it. It is a very human endeavour to practice art but she had the vision to understand this at a time and ultimately she did it for love of the art and the artists.