English version below –

Centrale nella ricerca artistica di Christian Holstad (Anaheim, California, 1972) è la demitizzazione degli eidola della società dei consumi: la merce giunta al termine del suo breve ciclo di vita viene recuperata e sottoposta ad un atto trasformativo, che ne fa strumento di denuncia delle contraddizioni insite nel sistema capitalistico e veicolo per narrazioni alternative. Parallelamente, l’artista va a riscoprire antiche metodologie di lavorazione e di impiego dei materiali, tecniche che sono tradizionalmente associate alla sfera dell’artigianato, restituendo loro dignità artistica. Proprio con tale finalità Holstad, californiano d’origine ma romagnolo d’adozione, ha sviluppato un progetto espositivo in due atti presso il Museo Civico Luigi Varoli di Cotignola (RA) che intende mettere in rapporto la tradizione locale di lavorazione della cartapesta con la ricerca che lui stesso conduce da più di vent’anni su questo materiale. La mostra, dal titolo Salve (10 marzo – 30 giugno), si inserisce in un più esteso progetto di valorizzazione del medium della cartapesta nell’arte contemporanea portato avanti dal curatore Gioele Melandri. Abbiamo posto all’artista alcune domande in merito alla mostra.

—-

Federico Abate: A Cotignola è in corso Salve, la tua prima personale in Romagna, articolata in due atti. Innanzitutto, a cosa si deve questo titolo?

Christian Holstad: Il linguaggio è strano. Trovo che anche la mia lingua madre, l’inglese, sia generalmente inadeguata a esprimere il mio modo di navigare nel mondo. Quando sono arrivato in Romagna volevo sapere come ci si rivolge agli anziani con rispetto, e mi hanno insegnato la parola “salve”. Deriva dal verbo latino salvēre, che significa stare bene, o essere in buona salute. In inglese “salve” si usa per indicare un unguento curativo. Mi piaceva l’idea di salutare qualcuno pensando a questo. Il saluto è anche un buon modo per iniziare a parlare una lingua. Guardo ai “punti di accesso” come catalizzatori per la realizzazione del mio lavoro. Durante la preparazione della mostra ho fatto visita a un amico. All’ingresso della casa c’è un pavimento in terrazzo con la parola SALVE che accoglie i visitatori. Il mio amico lo vede ogni giorno prima di entrare e uscire da casa sua. Diventa un mantra.

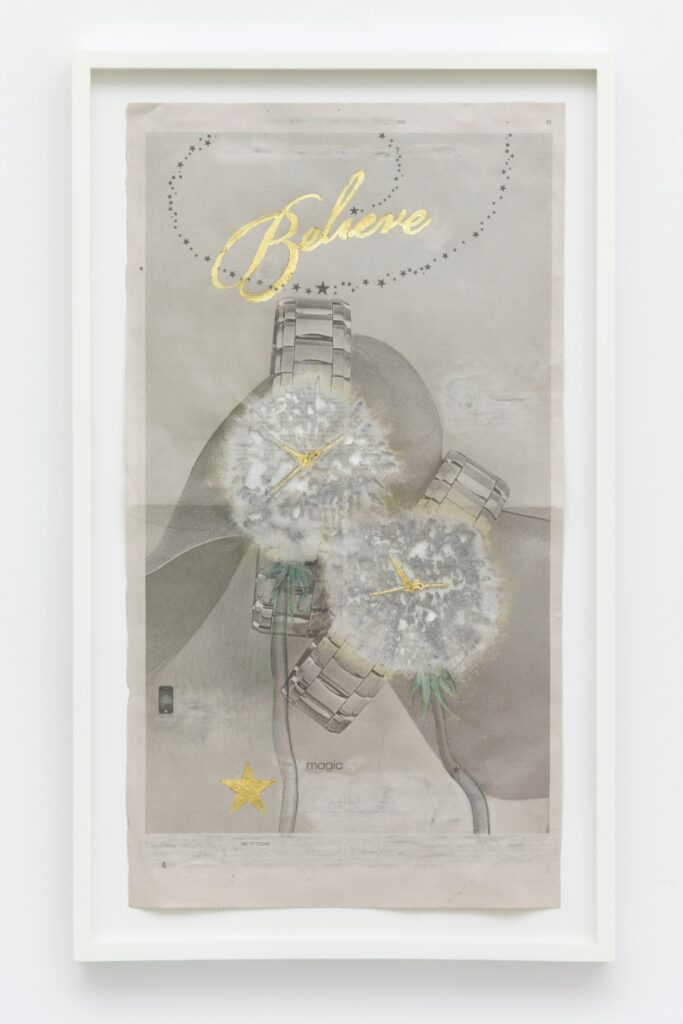

FA: Nel primo atto, A flutter of butterflies atop debris to reach our gentle heights, sono presenti alcuni tuoi vecchi lavori e un’installazione inedita dal titolo di Gentle Parade. Ci puoi parlare più approfonditamente delle opere esposte e di questa installazione?

CH: La prima parte della mostra presenterà un gruppo di palloncini di cartapesta. Ho iniziato a realizzarli 20 o 25 anni fa. Strappo la prima pagina di un giornale e la riassemblo in nuove immagini. Sopra di essi scrivo Life is a gift. La notizia in prima pagina rispecchia ciò che noi umani facciamo di questo dono.

C’è anche un mosaico di gusci d’uovo, che riproduce il pavimento in terrazzo di cui parlavo, poi due bidoni della spazzatura in ceramica cotta in fossa e una scultura realizzata con un carrello della spesa schiacciato e farfalle fatte a mano. Gioele Melandri, che ha curato la mostra, mi ha parlato della sagra di Cotignola, e io mi sono concentrato sulla sensazione e sul significato delle parole “gentle parade”, cercando di coltivare questa qualità.

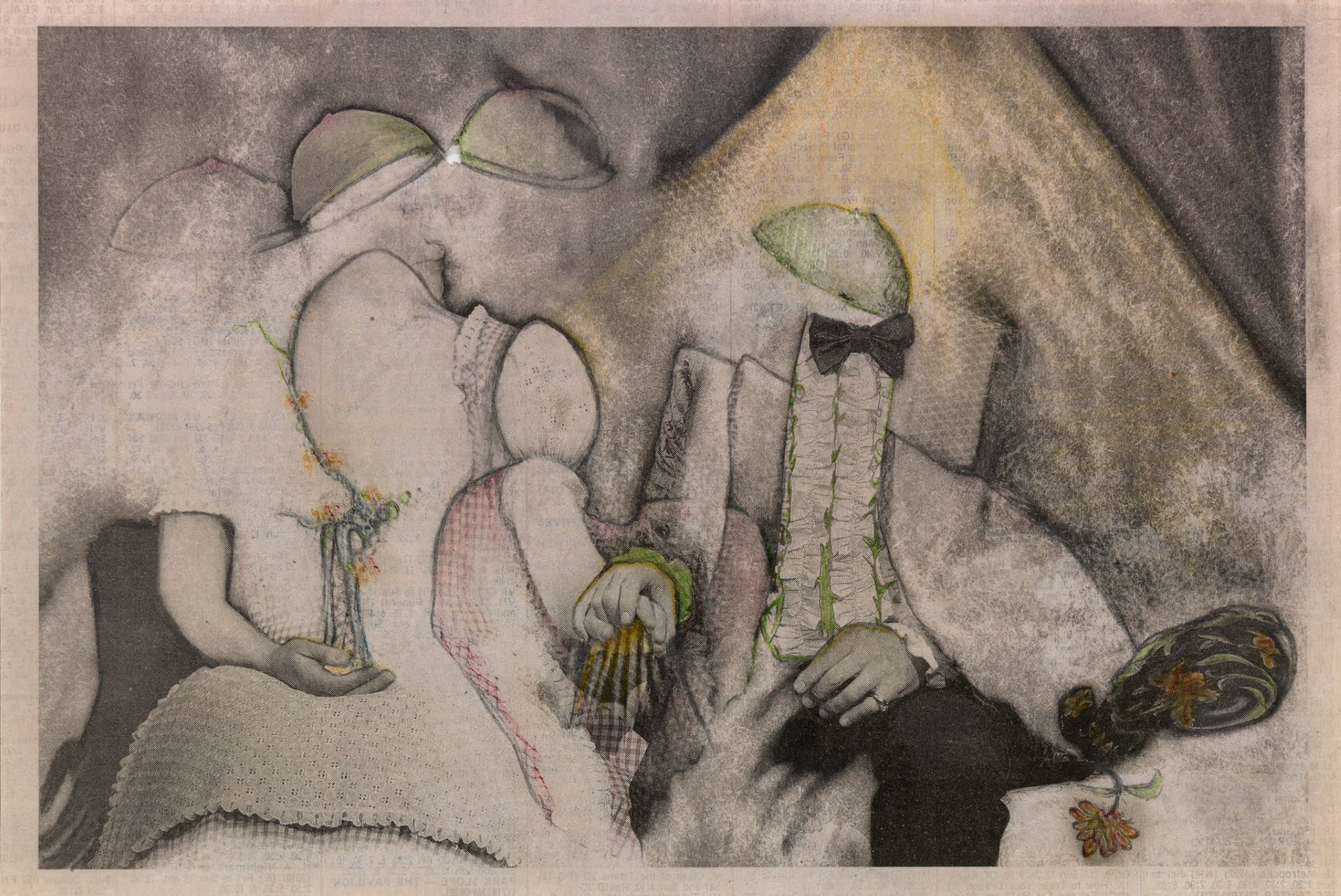

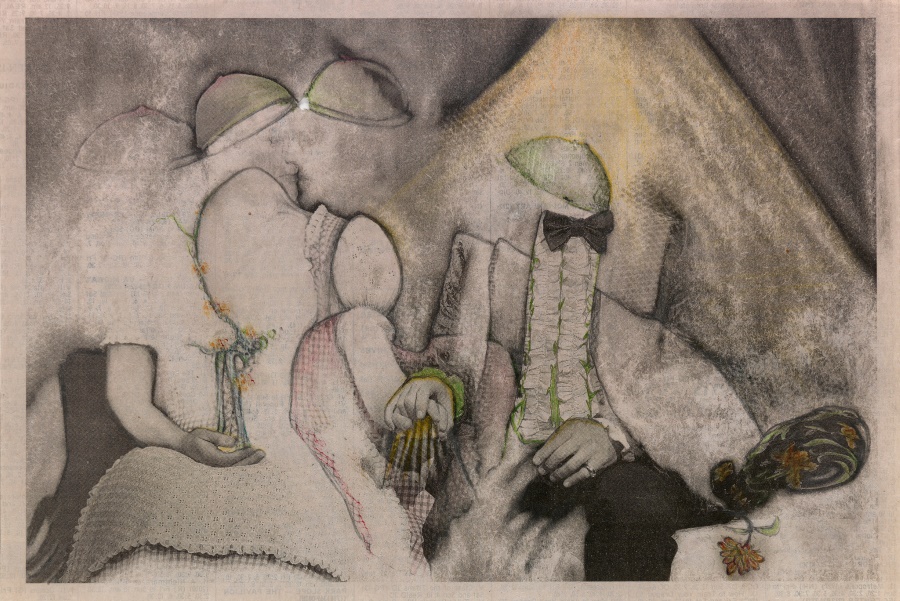

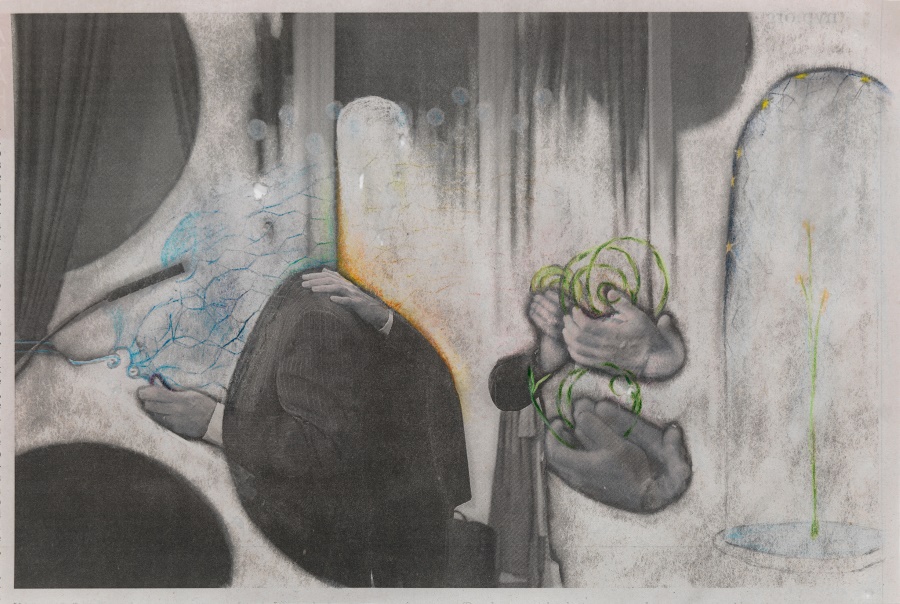

FA: A partire da sabato 12 aprile sarà invece la volta di Hello, prima occasione internazionale di riflessione su un tuo corpus di disegni realizzati su carta di giornale. In queste opere l’atto di comporre graficamente i soggetti si avvale anche dell’importante componente espressiva della cancellazione. Come si svolge il processo realizzativo di questi disegni? Che genere di storie vuoi raccontare?

CH: Uso una normale matita. Uso entrambe le estremità, sia la gomma che la grafite. Per me il processo è fare scultura. Mi interrogo e rispondo a quali immagini vengono scelte. Nelle fotografie si impiegano vari sfondi e angolazioni per spingere il punto di vista del giornale. Cosa succede quando si altera tutto questo?

FA: La carta di giornale e la tecnica della cartapesta sono presenti da molto tempo nel repertorio di materiali e linguaggi che impieghi nella tua ricerca artistica: lo attesta il fatto che alcuni dei disegni e delle sculture esposti in mostra datano già agli anni Novanta. In generale, nella tua pratica tendi a prediligere l’impiego trasformativo di materiali di riuso e di rifiuti, oppure tecniche “povere” che normalmente non sono ritenute degne di assurgere allo status di arte. A cosa si deve questo interesse?

CH: Penso ai rifiuti come al nostro es collettivo e al carrello della spesa come al nostro ego. Mi interessano i rifiuti e ciò che ci dicono di noi stessi. Come osserva Nicolas Bourriaud in Inclusioni, “la natura non produce né rifiuti né opere d’arte”. Ciò che apprezziamo e ciò che non apprezziamo ci dicono molto di noi stessi in egual misura.

FA: Il museo civico che ospita la mostra prende il nome da Luigi Varoli, un poliedrico artista locale noto soprattutto per le sue sculture in cartapesta, ed espone una serie di mascheroni raffiguranti personaggi della cittadina di Cotignola realizzati dall’artista per la sagra di Segavecchia. In che modo ritieni che le tue opere dialoghino con questi lavori di alto artigianato così profondamente legati al territorio e al suo folklore?

CH: Dopo la guerra Varoli ha utilizzato materiali di scarto come i sacchi di carta per la farina o il cemento, o i mattoni degli edifici distrutti, che ha usato per ottenere un colore rosa. C’è un senso di necessità – ha usato ciò che poteva trovare, trasformando i rifiuti in arte. Ha sentito anche un’urgenza: ha compreso l’importanza di portare gioia dopo ciò che la gente aveva subito. Questa connessione immediata con il qui e ora – opere realizzate per (e che parlano di) questa particolare comunità, di questo particolare territorio, fatte con materiali che hanno origine direttamente da esso – è il tipo di pratica artistica con cui mi relaziono ed è stato un punto di partenza per me.

Central to the artistic research of Christian Holstad (Anaheim, California, 1972) is the demythologization of the eidola of consumer society: commodities that have reached the end of their short life cycle are recovered and subjected to a transformative act, which makes them an instrument for denouncing the contradictions inherent in the capitalist system and a vehicle for alternative narratives. At the same time, the artist goes on to rediscover ancient methods of working and using materials, techniques that are traditionally associated with the sphere of craftsmanship, restoring artistic dignity to them. It is precisely with this purpose in mind that Holstad, a Californian by origin but a Romagnolo by adoption, has developed a two-act exhibition project at the Museo Civico Luigi Varoli in Cotignola (RA) that intends to relate the local tradition of papier-mâché work with the research he himself has been conducting on this material for more than two decades. The exhibition, titled Salve (March 10-June 30), is part of a more extensive project to enhance the medium of papier-mâché in contemporary art led by curator Gioele Melandri. We asked the artist some questions about the exhibition.

Federico Abate: Cotignola is hosting Salve, your first solo exhibition in Romagna. First, why did you choose this title?

Christian Holstad: Language is strange to me. I find even my mother tongue, English, generally inadequate to express my way of navigating the world. When I came to Romagna I wanted to know how to address elders with respect, and I was taught the word salve. It derives from the Latin verb salvēre, which means to be well, or to be in good health. In English ”salve” is a healing ointment. I liked the idea of greeting someone with this in mind. A greeting is also an entry point to speaking a language. I look to points of entrance as catalysts for making my work. While preparing the show I visited a friend. At the entrance of the house is a terrazzo floor spelling the word SALVE to greet visitors. My friend sees this daily before entering and exiting his home. It becomes a mantra.

FA: The exhibition will be divided into two acts. The first one, A flutter of butterflies atop debris to reach our gentle heights, features some of your old works and a brand-new installation entitled Gentle Parade. Can you tell us more about the works on display and this installation?

CH: The first part of the show will show a group of papier maché balloons. I started making these 20 or 25 years ago. I tear the front page of a newspaper and reassemble it into new images. In script I write “Life is a gift”. The news on the front page mirrors what we humans do with this gift.

There is also an eggshell mosaic, reproducing the terrazzo floor I was mentioning, two pit-fired ceramic trash cans and a sculpture made from a smashed shopping cart and hand-made butterflies. Gioele Melandri, who curated the show, told me about the parade of Cotignola, and I focused on the feeling and meaning of the words ”gentle parade”, and tried to cultivate this quality.

FA: From April 12, it will instead be the turn of Hello, the first international opportunity to reflect on a body of your drawings made on newsprint. In these works, the partial erasure of what is printed on the newspaper page plays a crucial role in the final result. Can you describe the process of making these drawings? What kind of stories do you want to tell?

CH: I use an ordinary pencil. I use both the eraser and graphite ends. For me the process is sculpting. I am questioning, responding to what images are chosen. Different backgrounds and camera angles are used to push the newpaper’s viewpoint. What happens when you alter that?

FA: Newsprint and the papier-mâché technique have long been present in the repertoire of materials and languages you employ in your artistic research: this is attested to by the fact that some of the drawings and sculptures on display in the exhibition date back to the 1990s. In general, in your practice, you explore the transformative potential of recycled materials, or traditional techniques commonly not associated with art making. Can you talk more in-depth about this interest of yours?

CH: I think of trash as our collective id, and the shopping cart as our ego. I am interested in waste and what it tells us about ourselves. As Nicolas Bourriaud remarks in Inclusions, ”nature produces neither waste nor works of art”. What we value and what we don’t, both are very revealing.

FA: The civic museum hosting the exhibition is named after Luigi Varoli, a multifaceted local artist best known for his papier-mâché sculptures. In the collection is displayed a series of masks depicting people from the town of Cotignola made by Varoli for the Sagra della Segavecchia. How do you think your works dialogue with these sculptures of high craftsmanship, so deeply connected to the local folklore?

CH: After the war Varoli used discarded materials like the paper bags for flour or cement, or brick from destroyed buildings, which he used to get a pink color. There’s a sense of necessity — he used what he could find, turning waste into art. There’s also an urgency: he saw the importance of bringing joy after what the people had suffered through. This immediate connection to the here and now — works made for and that speak about this particular community, this particular territory, made from materials that directly stem from it — this is the kind of art practice I relate to, and was a starting point for me.