On a grey day of middle April I walk towards the DoubleTree Hotel to meet the avant-garde filmmaker and poet Jonas Mekas. The founder of the Anthology Film Archives, the Filmmakers’ Cooperative and ‘Film Culture’ magazine, has just been part of an event in partnership with MUBI, Serpentine Galleries and the Lithuanian Culture Institute, followed by the launch of ‘Conversations with film-makers’ (published by Spector Books). Sitting at a table in a quiet corner of the hotel restaurant, we start talking about poetry and dreams, the avant-garde, his newest book publication and upcoming projects.

Giulia Ponzano: On the 10th April at PeckamPlex, while watching ’Outtakes from the Life of a Happy Man’ (2012), I thought of the Ancient Greek poet Sappho. I see her clarity of language and simplicity of thought, how she was looking into the burning centre of ordinary things and how she was expressing pure wonder for almost invisible moments, reflected in your work.

Jonas Mekas: My work is less personal I would say. The diary form is supposed to be personal, but there are diaries and diaries, like the ones by Anaïs Nin or Sappho: these two were much more personal. I’m recording more the outside, because the camera catches what is in contact with and, Anais Nin, for example, was recording more what is inside. My ‘inside’ in my films is recorded very indirectly and those women artists recorded very directly.

GP: But you share an interest to document the presentness, to give attention to the moment as it happens.

JM: Yes, definitely, my cinema is a celebration of the present and of reality.

GP: During the interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist, you reminded us that ‘panta rei’(all flows, Heraclitus) and then you mentioned ‘The waves’ by Virginia Woolf. Tell me something about movement/change.

JM: Have you read ‘The Waves’?

GP: Not yet, I bought the book yesterday. I still have to discover the meaning of the waves.

JM: I’m not interested in the meaning of it, when I’m reading a book I’m more interested in the way the author talks about certain things. I’m interested in how she writes, the language she uses. The point of the waves was not interesting at all, I thought that the content was almost boring. The same happens in the arts: it excites me the way how Picasso, Monet, Van Gogh painted, not so much their subjects. The same for Sappho, there were many many artists talking about love and beauty, but from the fragments that survived, she still stands out.

GP: What about the fragments, do they contain the whole?

JM: Yes, even the smallest fragment still reveal the style. Think about Emily Dickinson, one of her single line cannot be mixed up with anyone else. And the same happens in cinema.

GP: Are you still writing poems?

JM: Yes, I’m still writing but in a different way. All of my early poems are written in Lithuanian, while now, when I write, I write in English and since this has not been my mother tongue I’ve had to invent my own form in which I could write even in an adopted language. The form I took up for myself have been the one of postcards and letters. These don’t have to be perfect in a way. So, now, most of my poetry consists in letters to friends.

GP: What were you writing when you were a kid?

JM: I did not know how to write, I kept a diary where I was mostly making drawings. It was my lens, it was my camera. I have always been down-to-earth, very realistic because I grown up in a farm where everything was real, there was not so much dreaming.

GP: In a 2008 interview you mentioned ‘Cuore’ by Edmondo De Amicis. How did this work influence you?

JM: Yes, it was very influential for me. I read it when I was ten years old – it’s a diary written from a kid. I was impressed, in a way it strengthen my desire to keep a diary.

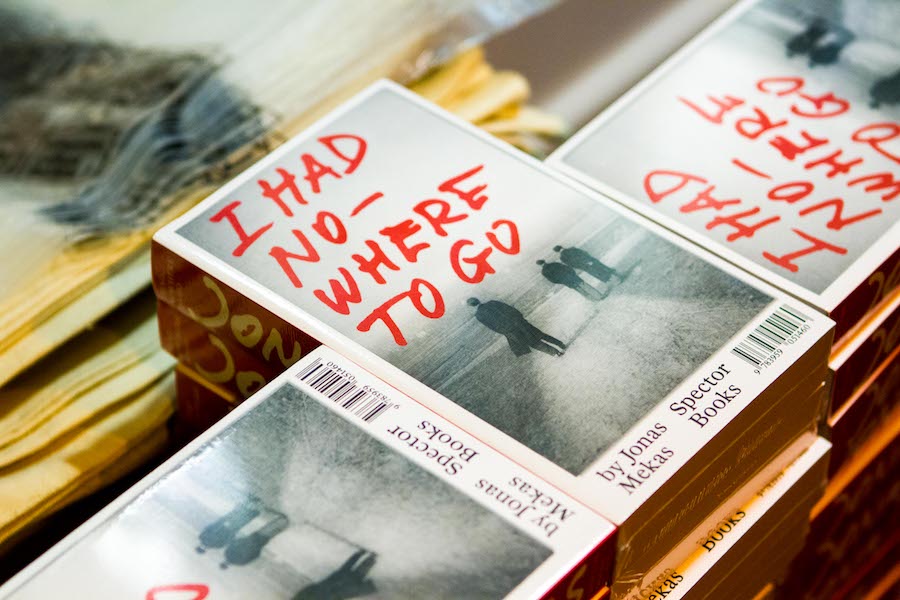

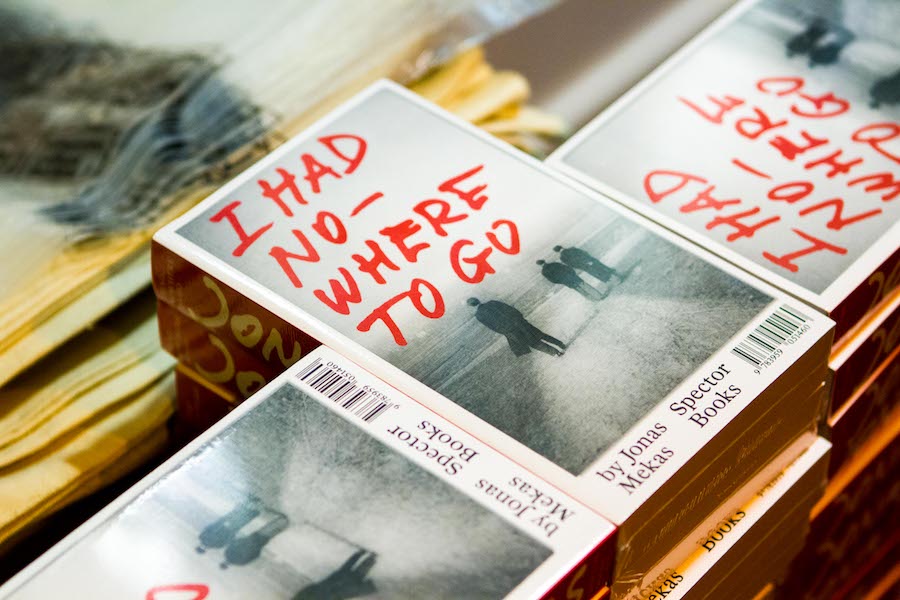

GP: ‘Conversations with film makers’, your new book, is a compilation of sixty interviews which you conducted on behalf of the Village Voice from 1958 until 1977. What is the idea behind the book?

JM: Most of those conversations have been published between 60’s – 70’s and were in the Village Voice where I used to write for about 20 years. They are all with non commercial film-makers and avant-garde artists, so the book is about different forms of cinema, not about the conventional, narrative one. Those who tried to develop new different poetics and other kind of form of cinema. There was a lot of that happening in the States but also in Europe, including in Italy. Little Cooperatives were rising in various cities of Italy as well. The same in England and Germany too. But they did not really continue in Italy, the movement expanded mostly in England and US. There were not possibilities to screen in Italy, there were very few universities and places available. One that continued the avant-garde tradition was my friend Tonino de Bernardi, in Turin.

GP: How did you come up with the idea of publishing these interviews now?

JM: I was asked by a young publishing house Spector Books, based in Leipzig in Germany, if I had something for them. I told them that those columns should have been collected and should be available because when they are together, sixty/seventy of them, they give a very good idea of what was happening in that period; the concerns of the filmmakers and also some ideas about different forms of cinema.

GP: When did the video enter in your life? How has the advent of new technologies affected your relationship to filmmaking?

JM: It affected what I was doing in cinema and how I was disseminating my work. Now it’s so much easier, faster and cheaper. In film you have to spend money, in printing and repairing damages and so on. With Internet it’s so much easier.

GP: Are you still using film sometime?

JM: No, I don’t film, I switched to video almost thirty years ago.

GP: Do internet and digital video help make experimental cinema more viable?

JM: No, I don’t think so. But first I should to tell you that I’m very much against the term ‘experimental’: because no filmmaker that I know experiments, filmmakers just make the films and they know what they want to and how to do it, there is not experimentation. I don’t know who invented that term. There are different forms of narratives and then there are many other non-narrative forms – which are poetics forms, from short pieces like haiku, to Dante. The same happens in cinema. So when Tonino de Bernardi or Stan Brackage made their film they did not experiment. The word ‘experimental’ seems not serious, but actually Stan Brackage films are as serious as the ones of Scorsese. It’s just that one is a poem and the other one is a novel and it goes under cinema.

GP: Which word should I use instead of ‘experimental’ then?

JM: Poetic Cinema.

GP: Have you had the chance to visit some Virginia Woolf spots here in London?

JM: Yes, here in Bloomsbury. We went to the Lamb, the pub just around the corner. When I walked in there was none, no tourists no music, a very nice pub. I visited also her house.

GP: Future projects?

JM: More shows and books. Besides my ‘Personale’ at Palazzo della Ragione in Bergamo I have a project with Missoni in New York and another event at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary art in Seoul. The biggest projects I’m working on consists in building the library for the Anthology Film Archive, which will collect audio-visual and paper materials.

GP: And what about today?

JM: Today is quiet for me, I’m ready to go back home.