Quest’anno, Ibrida si fa Moltitudine: il Festival Internazionale delle Arti Intermediali di Forlì giunge alla sua decima edizione e celebra il proprio anniversario con quattro giorni di eventi, dal 25 al 28 settembre, al crocevia tra videoarte, performance art, installazioni interattive, musica, live cinema, talk e workshop, a cui si aggiunge l’assegnazione di cinque premi nazionali e internazionali. I Direttori Artistici Francesca Leoni e Davide Mastrangelo completano il denso programma di quest’edizione speciale con un’importante ‘mostra collettiva intermediale’ dal titolo Anatomie Digitali, allestita alla Fondazione Dino Zoli. «Nel decimo anniversario di Ibrida Festival, abbiamo immaginato il corpus delle opere raccolte in questi anni come un grande organismo in divenire. Un corpo che cresce, muta, si evolve. E attraverso un gesto simbolico, quasi chirurgico, abbiamo tracciato un taglio per individuare alcuni degli organi vitali: opere emblematiche, artisti significativi, visioni che hanno segnato profondamente il percorso del Festival – spiegano i curatori – Non si tratta, dunque, di una semplice retrospettiva. Ma di una dissezione poetica e curatoriale. Un’indagine stratificata sul modo in cui il corpo, l’immagine, la tecnologia e il linguaggio video si sono trasformati nell’ultimo decennio. Un viaggio attraverso cinque sezioni tematiche che esplorano il gesto, la performance, l’animazione, il glitch, l’intelligenza artificiale e l’ibridazione dei codici». L’esposizione (già inaugurata e aperta fino al 12 ottobre) presenta le opere di ben 55 artisti provenienti da 15 paesi: tra questi, accanto a grandi nomi come Robert Cahen e Regina José Galindo, l’ospite d’onore è Gary Hill (Santa Monica, 1951), Leone d’oro alla Biennale di Venezia nel 1995 e pioniere della videoarte. Hill, che prenderà anche parte ad un talk previsto per sabato 27 settembre (tutti i dettagli sul sito), si è gentilmente prestato a rispondere ad alcune nostre domande sulla sua serie di opere in mostra, sulla sua poetica e, per concludere, sul suo rapporto con il nostro Paese.

English version below

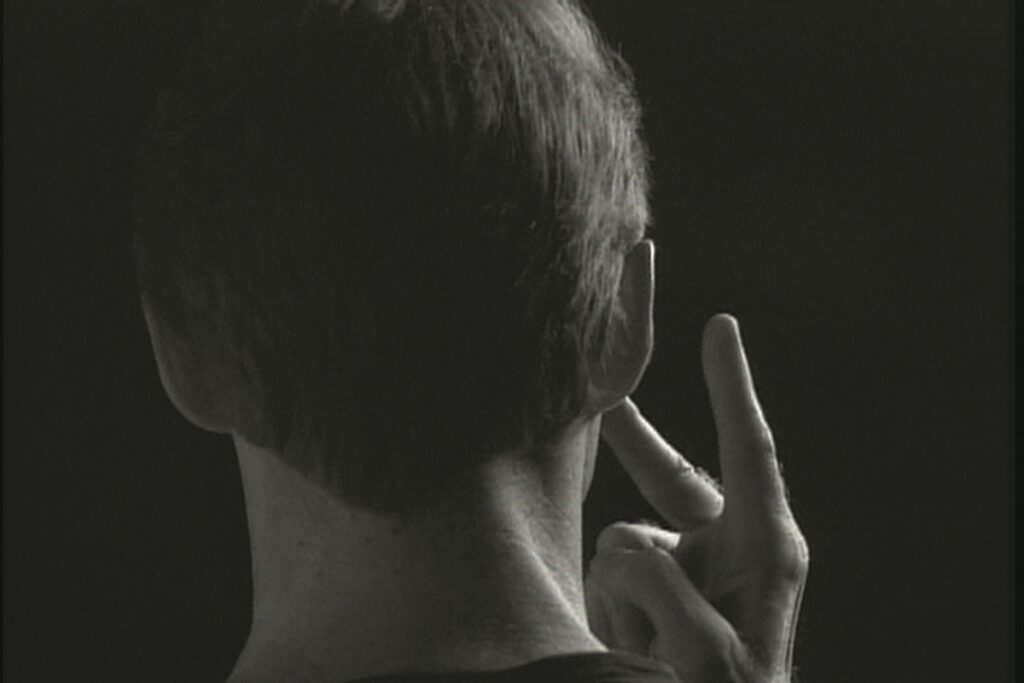

Federico Abate: Nella mostra Anatomie digitali sarà esposta la tua serie SELF ( ): cinque dispositivi bianchi, simili a strumenti medici, ciascuno dotato di un oculare, all’interno del quale lo spettatore vede frammenti disarticolati della propria corporeità catturati in tempo reale – e distorti – da sensori posizionati alle estremità che lo circondano. L’opera, dunque, mette chi la fruisce di fronte ad una versione aliena del proprio sé, in cui forse non può riconoscersi, e suscita un senso di inquietudine affine al “perturbante”. Con SELF () cosa intendi suggerire sulla nozione di identità o sul concetto di “sé” in rapporto alle evoluzioni della tecnologia e alla società contemporanea?

Gary Hill: Dopo averne fatto esperienza, si potrebbero vedere i “dispositivi” come una sorta di ‘altro’ in attesa. Una volta attivati dalla presenza di uno spettatore, si verifica un istante di tempo sfocato, un momento in cui lo spettatore si sente distaccato da se stesso: un altro sé è entrato in scena, per così dire. E poi subentra una consapevolezza secondaria venata di paranoia: qualcuno, qualcosa di altro è coinvolto, in modo simile alla sorveglianza, o forse alla sorveglianza rivoltata al contrario.

FA: L’esperienza intima sollecitata da SELF ( ) e la sua modalità di fruizione mi ricordano dispositivi della preistoria del cinema come lo stereoscopio o il mutoscopio, ma anche il gesto voyeuristico del guardare da una fessura. Questo è un tropo ricorrente dell’arte dell’ultimo secolo: da Étant donnés di Duchamp in poi, gli artisti hanno usato questo approccio per indagare a fondo i desideri e le pulsioni dello spettatore, mettendolo in condizione di “guardare senza essere guardato”. Tuttavia, nella tua opera, ciò che si incontra al di là dell’oculare non è l’altro da sé, ma il proprio sé destrutturato, e dunque lo sguardo voyeuristico si rovescia su se stesso. Lo spettatore, pur nell’intimità della sua esperienza di fruizione, si ritrova non solo a vedere tracce del suo essere che non riconosce, ma anche a “vedersi visto”, come in certi lavori storici di Bruce Nauman. Quali sono i tuoi pensieri in merito al rapporto tra artista, opera e spettatore? Cosa significa, oggi, proporre un’esperienza così fisica e individuale nella fruizione dell’immagine, la quale peraltro non è documentabile ed esiste solo nel momento dell’interazione?

GH: Si tratta effettivamente di una costruzione a circuito chiuso, ma camuffata da dispositivo visivo, sebbene sia in grado di riportare chi lo guarda in una sorta di iper-presenza. Non lo considero tanto una decostruzione, che forse è un concetto troppo meccanico e didattico. L’esperienza è più confusa, c’è un momento in cui non si capisce chi o cosa sia ciò che si vede, ma non appena entra in gioco la propriocezione, improvvisamente lo si percepisce come una parte di sé. Tuttavia, rimane ancora il dubbio su quale parte del mio corpo si stia guardando o dove si trovi quel motivo o quella trama sui propri vestiti, per non parlare di come avvenga, come se fosse per magia o per un gioco di prestigio. Essendo primi piani estremi, le immagini non sono le tipiche immagini di sorveglianza. Suppongo che siano più simili alle immagini mediche. Quando ero giovane, ho subito un intervento endoscopico per controllare i ventricoli, poiché avevo il cuore ingrossato. Ero sveglio e ho guardato la telecamera risalire lungo la vena ed entrare nelle aree intorno al cuore su un monitor video. Se questa fosse stata l’ispirazione per il lavoro, equivarrebbe a un periodo di gestazione di circa sessant’anni!

FA: Credi che questo disallineamento tra ciò che vediamo e ciò che ci aspettiamo di vedere, tra la familiarità del sé e la sua astrazione, possa generare una nuova consapevolezza nello spettatore? È un modo per spingerlo a interrogarsi non solo su come si rappresenta, ma su chi è, fuori dall’immagine?

GH: Forse tutto ciò che dici è “corretto”. Eppure, immagina che io stia riflettendo su come far funzionare tutto questo. Non mi viene in mente nulla di simile a come posso generare una nuova consapevolezza nello spettatore, o niente di vagamente simile.

Allargando lo sguardo, le possibilità offerte dalla cibernetica e dai media in tempo reale sono ancora interessanti per sperimentare il “sé”. In una certa misura, questo potrebbe essere considerato un parallelo alla ricerca psichedelica, specialmente quando i due elementi sono combinati, come esemplificato dallo scrittore e artista multimediale Paul Ryan, autore di Cybernetics of the Sacred and Video Mind, e dall’uso di vasche di isolamento e LSD da parte di John C. Lilly. Ora, questo aspetto si è notevolmente diffuso.

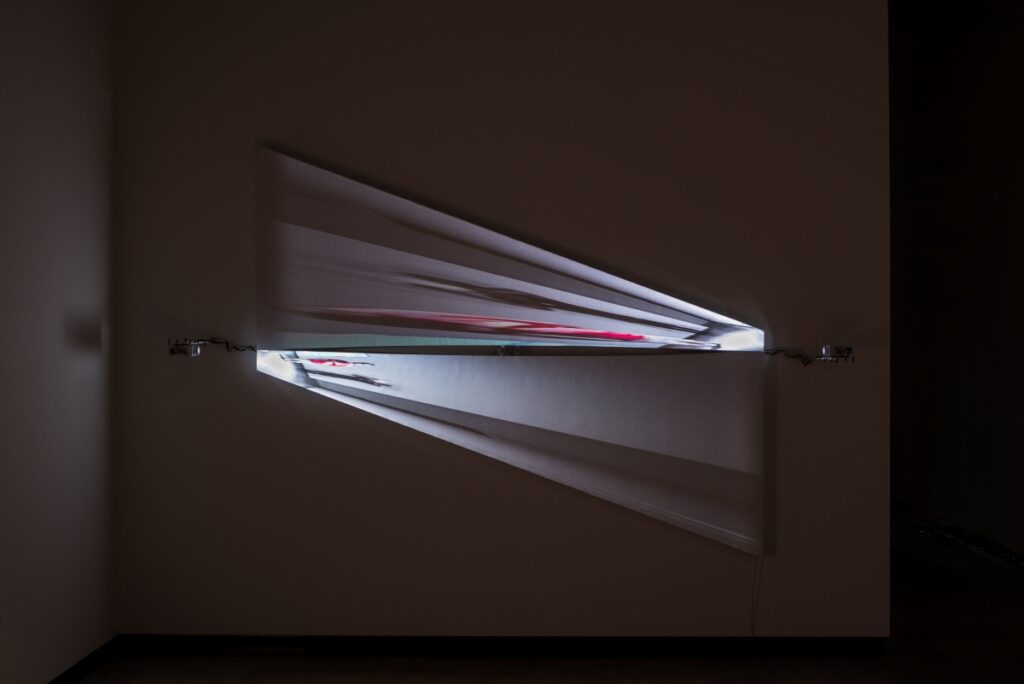

Una volta che ho iniziato a giocare con le microcamere, ne sono diventato ossessionato e mi ci sono immerso completamente. Ho realizzato diverse opere utilizzando questa microtecnologia, in particolare Dream Stop, che incorpora 31 telecamere nascoste in una struttura simile a un acchiappasogni. Quando gli spettatori entrano nello spazio, si ritrovano proiettati ovunque in orientamenti casuali, sovrapposti e con un effetto olografico. Nello stesso periodo ho realizzato una serie intitolata Accelerated paintings: Cornered, Painting with Two Balls (after Jasper Johns) e Tripyramid, tutte del 2016. Tutte e tre le opere incorporavano microcamere nascoste in modi diversi, incorporando gli spettatori nelle opere: la loro immagine era mappata, in ciascuna opera, sui particolari tronchi di piramide proiettati.

L’idea di usare queste telecamere grandi come un’unghia potrebbe essere nata dall’uso di piccoli monitor, in realtà mirini di videocamere di piccolo formato, considerandoli come oggetti materiali e pensando che anche loro potessero proiettare immagini come luce, come in And Sat Down Beside Her, 1990.

Nel romanzo The Painted Bird c’è un passaggio in cui un bambino vede un gatto che gioca con gli occhi appena strappati a un bracciante accusato di aver spiato nella camera da letto del padrone. Il ragazzo immagina di prenderli e di metterli in luoghi strategici per poi recuperarli in un secondo momento, pensando di poter scoprire cosa è successo in sua assenza.

FA: La tua opera accoglie il pubblico nella sezione ‘Genesi’, accanto a un lavoro di un altro protagonista della storia della videoarte, Robert Cahen. È in effetti ben noto il tuo ruolo pionieristico nello sviluppo del linguaggio del video, fin dagli anni Settanta. Come ritieni che siano cambiati i codici espressivi del video oggi rispetto a quando hai iniziato ad esplorarne le potenzialità?

GH: Ho iniziato come scultore. Quando mi sono imbattuto per la prima volta nel video, cosa che in realtà è avvenuta per caso, questo mezzo stava attraversando una fase altamente sperimentale. All’epoca non era legato al mondo dell’arte. C’era un’energia frenetica intorno ad esso. È stata una rivoluzione su molti livelli, simile al modo in cui Bitcoin è nato con la speranza di una moneta forte/energia che fosse decentralizzata. L’aspetto singolare che distingue davvero il video, facendo una differenza sostanziale, è la sua natura in tempo reale e intrinsecamente cibernetica. Fondamentalmente, non è un film, né è semplicemente basato sulle immagini; è invece un potente strumento cibernetico in grado di coinvolgere chi lo guarda in uno stato continuo di divenire. Anche se le persone lo usano certamente come un dispositivo facilmente disponibile per realizzare “film”, in realtà questo non è il suo vero scopo o la sua ragion d’essere.

E sì, la parola chiave è “codice”. Se è vero che la programmazione cerca intrinsecamente un risultato specifico e predeterminato e non può essere considerata veramente “in tempo reale” nel senso di una creazione spontanea e in evoluzione, questa natura orientata all’obiettivo non permette di cogliere l’essenza dell’arte. Allo stesso modo, il significato del soggetto in un dipinto, in un film o in un’installazione video, o la tecnologia impiegata nella sua creazione, non determinano da soli il suo valore artistico. Ciò che rende qualcosa arte è invece il modo in cui si manifesta o si esprime, indipendentemente dalla particolare tecnologia o dal soggetto coinvolto.

Da questo punto di vista, nuovi “codici espressivi” possono certamente essere applicati ai mezzi artistici, ma tali codici non definiscono né costituiscono l’arte stessa.

Abbiamo assistito a secoli di sviluppo tecnologico utilizzato nella creazione artistica, con una velocità e una portata in crescita esponenziale. Tuttavia, che dire dell’aspetto sfidante del coinvolgimento umano in un processo intimo e profondamente vulnerabile, una sorta di pathos che esiste da sempre nella storia dell’umanità? Possiamo immaginare uno “sviluppo” nell’essenza stessa dell’essere umano che potrebbe trasformare l’arte dall’interno?

In questo momento, l’elefante nella stanza è: non farò nomi, ma le sue iniziali sono AI. È ironico che si debba ricorrere a stimoli (usare il linguaggio) per suscitare una reazione, almeno per ora. La fase attuale è, relativamente parlando, né qui né là. Forse quando emergeranno l’AGI e l’ASI, l’arte (e la vita [e la morte]) cambieranno profondamente. Non ho altra scelta che attendere quel momento.

FA: Nei primi anni Settanta parlavi del video come del “medium più vicino al pensiero”. È ancora così, o è cambiato qualcosa con l’avvento delle nuove tecnologie?

GH: Mi correggo e dico che è la scrittura ad essere più vicina al pensiero, e sì, il video è una forma di scrittura, o almeno può esserlo. D’altra parte, sfruttando l’aspetto in tempo reale del video, esso può bypassare il linguaggio come un arco elettrico e creare una sorta di pensiero viscerale.

FA: Hai esposto più volte nel nostro Paese, collabori con la Galleria Lia Rumma e hai concepito in più occasioni degli interventi site-specific in dialogo con il nostro patrimonio artistico e architettonico. Come descriveresti il tuo legame con l’Italia?

GH: Dinamico: un intricato intreccio di relazioni ed esperienze.

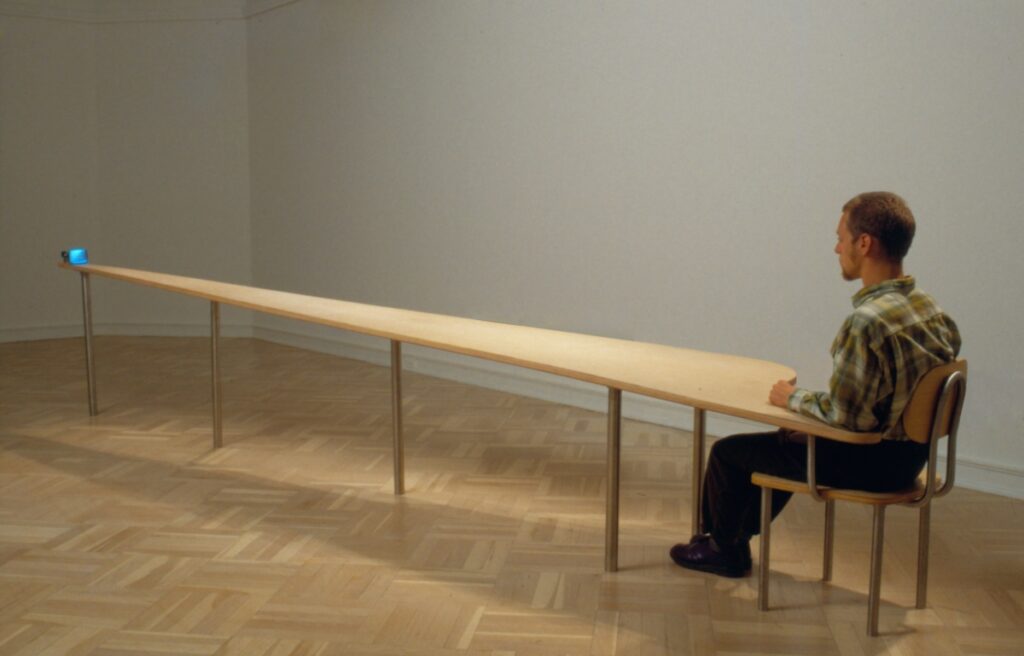

Se la memoria non mi inganna, la prima mostra in Italia fu alla Biennale di Venezia del 1995, dove fu installato Withershins. Durante la settimana dell’installazione piovve a dirotto e gran parte dell’opera fu allagata, compresi i cavi elettrici e i tappetini sensibili utilizzati per attivare i testi parlati. Fu una catastrofe. Quando si discusse su cosa si potesse fare, gli organizzatori dell’evento dissero: “Beh, siamo tutti sulla stessa barca”. Effettivamente. Ciononostante, l’opera fu in qualche modo completata per l’inaugurazione. Seguì la prima di quattro mostre personali con la Galleria Lia Rumma di Napoli (e imparai un modo diverso di guidare l’auto!). Sono state installate Learning Curve (still point), 1993, e Clover, 1994. Nel 2000 ho preso parte ad una residenza presso l’American Academy in Rome. Si è verificato un difficile episodio di depressione e per il resto del soggiorno ho consultato uno psichiatra freudiano due volte alla settimana. In qualche modo, Goats & Sheep, 1995/2002, è stato comunque realizzato. Contemporaneamente, Wall Piece è finito alla 49ª Biennale di Venezia, ma solo dopo un lungo viaggio in treno con il curatore Harald Szeemann. Facemmo una visita al CEO di United Colors of Benetton alla ricerca di finanziamenti per il progetto, ma non siamo riusciti a convincerlo.

Nel 2005 ho imparato rapidamente a conoscere i tentacoli nascosti della politica che circondano il Colosseo, dove è stata esposta l’installazione Resounding Arches ed è stata realizzata un’elaborata performance, Dark Resonances, con diversi collaboratori. In concomitanza con l’ultima mostra, Ghost Chance, alla Galleria Lia Rumma di Napoli, ho realizzato un libro d’artista, Inasmuch as It Has Already Taken Place, commissionato dallo scrittore Gabriel Guercio e dalla Juxta Press per un progetto intitolato Afterlife. Purtroppo, la mostra prevista delle opere è stata annullata a causa del Covid.

Forse l’esperienza più strana che ho vissuto in Italia è stata quella di entrare nel Museo del Real Bosco di Capodimonte a Napoli e vedere una scultura in filo metallico che avevo realizzato nel 1967 (?). Era stata originariamente commissionata da Marshal Backlar, il produttore del film sullo skateboard Skaterdater in cui recitavo. Ancora oggi non ho idea di come e perché si trovasse in quel museo.

Tutto sommato, una pazza avventura italiana…

FA: Hai avuto occasione di seguire l’evoluzione della videoarte italiana? Ci sono artisti italiani che lavorano con il video (o con altri linguaggi espressivi), con cui senti di avere delle affinità?

GH: No. È difficile stare al passo con qualsiasi tipo di evoluzione, compresa la mia! La buona notizia è che seguirò un corso intensivo ai festival Over the Real e Ibrida e non vedo l’ora di farlo.

Federico Abate: In the exhibition Digital Anatomies, your series SELF ( ) will be on display: five white devices, reminiscent of medical instruments, each equipped with an eyepiece through which the viewer sees disjointed fragments of their own body, captured in real time – and distorted – by cameras placed at the surrounding extremities. The work, therefore, confronts the viewer with an alien version of their own self, in which they may not be able to recognize themselves, and evokes a sense of unease akin to the “uncanny.” With SELF ( ), what do you intend to suggest about the notion of identity or the concept of the “self” in relation to technological developments and contemporary society?

Gary Hill: After the fact of experience, one might see the “devices” as a kind of other in waiting. Once activated by the presence of a viewer, there is an instant of smeared time—a moment in which the viewer feels displaced from themselves—another self has entered the picture so to speak. And then a secondary awareness kicks in tinged with paranoia—someone, something other is involved not unlike surveillance, or perhaps surveillance turned inside out.

FA: The intimate experience prompted by SELF ( ) and its mode of viewing remind me of pre-cinematic devices such as the stereoscope or the mutoscope, but also of the voyeuristic act of peering through a peephole. This is a recurring trope in art over the last century: from Duchamp’s Étant donnés onwards, artists have used this approach to probe the desires and drives of the viewer, placing them in a position of “looking without being seen.” However, in your work, what lies beyond the eyepiece is not an ‘other’, but one’s own deconstructed self, and thus the voyeuristic gaze is turned back upon itself. The viewer, even in the intimacy of their experience, finds themselves not only seeing traces of their own being that they do not recognize, but also “seeing themselves being seen,” as in certain historical works by Bruce Nauman. What are your thoughts on the relationship between artist, artwork, and viewer? What does it mean, today, to propose such a physical and individual experience of viewing the image – an image that, moreover, is not documentable and exists only in the moment of interaction?

GH: It is indeed a closed-circuit construction but camouflaged as a seeing contraption, albeit one that loops one back into a kind of hyper-presence. I don’t think of it so much as a deconstruction, that’s maybe too mechanical and didactic. The experience is messier, there’s a glitch moment of not knowing who or what it is but as soon as your proprioception kicks in you suddenly kind of own it. Nevertheless, there’s still the query of what part of my body is that or where on my clothing is that pattern or texture, not to mention, how is it happening, as if it’s by way of magic or sleight of hand. Being extreme close-ups, the images aren’t your typical surveillance image. I suppose it’s closer to medical imaging. When I was young, I had an endoscopic procedure done to check my ventricles since I had an enlarged heart. I was awake at the time and watched the camera go up my vein and into areas around my heart on a video monitor. If that were possibly the inspiration for the work, it would equate to about a sixty-year period of gestation!

FA: Do you think that this misalignment between what we see and what we expect to see – between the familiarity of the self and its abstraction – can generate a new awareness in the viewer? Is it a way of prompting them to question not only how they represent themselves, but who they are, beyond the image?

GH: Perhaps everything you say is “correct.” And yet, Imagine I’m contemplating how to make this work. Nothing comes to mind akin to: how can I generate a new awareness in the viewer or anything remotely similar.

Zooming out, the possibilities of cybernetics and real-time media are still compelling for experiencing the “self.” To a certain degree, this could be considered a parallel to psychedelic research, especially when the two elements are combined, as exemplified by the writer and media artist Paul Ryan, who wrote Cybernetics of the Sacred and Video Mind, and John C. Lilly’s use of isolation tanks and LSD. Now, this element has proliferated considerably.

Once I started playing around with micro cameras, I became obsessed and immersed myself. I made several works utilizing this micro technology, notably Dream Stop that incorporates 31 hidden cameras in a dreamcatcher-like structure. When viewers enter the space, they find themselves projected all over in random orientations, overlapping and having a holographic feel about them. Around the same time, I did a series entitled “Accelerated paintings,” Cornered, Painting with Two Balls (after Jasper Johns), and Tripyramid, all 2016. All three works incorporated hidden micro cameras in different ways enfolding the viewer into the works—their image mapped to the particular projected frustums of each work.

The incentive for using these fingernail-sized cameras might have originated from using tiny monitors, actually viewfinders of small format video cameras, and treating them as materiality and that they too could project image as light as in And Sat Down Beside Her, 1990.

There’s a passage in the novel The Painted bird in which a child sees a cat playing with freshly plucked out eyes of a farm hand who was accused of spying into the master’s bedroom. The boy imagines taking them and placing them at strategic locations only then to fetch them at a later time thinking he could find out what happened in his absence.

FA: Your work welcomes visitors into the “Genesis” section, alongside a piece by another key figure in the history of video art, Robert Cahen. Your pioneering role in the development of the video language, since the 1970s, is well known. How do you think the expressive codes of video have changed today compared to when you first began exploring its potential?

GH: I began as a sculptor. When I first encountered video, which was, in fact, happenstantial, it was going through a highly experimental phase. At that time, it wasn’t tethered to the art world. There was a giddy energy about it. It was a revolution on many levels, similar to the way Bitcoin began with the hope of a decentralized hard money/energy. The singular aspect that truly sets video apart, making a substantial difference, is its real-time and inherently cybernetic nature. Fundamentally, it is not film, nor is it merely image-based; instead, it’s a powerful cybernetic tool capable of engaging one in a continuous state of becoming. While people certainly use it as a readily available device for making “films,” that, in fact, is not its true purpose or raison d’être.

And yes, the code word is “code.” While programming inherently seeks a specific and predetermined result, and cannot truly be considered ‘real-time’ in the sense of spontaneous, evolving creation, this goal-oriented nature doesn’t get one into the guts of what art is. Similarly, the significance of the subject in a painting, film, or video installation, or the technology employed in its creation, does not solely determine its artistic value. Instead, what makes something art is the manner in which it is manifested or expressed, independent of the particular technology or subject matter involved. From this perspective, new ‘expressive codes’ can certainly be applied to art media, but these codes do not define or constitute art itself.

We have witnessed centuries of technological development used in art making, with exponentially increasing speed and scope. However, what about the challenging aspect of human engagement in a process that is intimate and profoundly vulnerable—a kind of pathos that has existed throughout human history? Can we envision a ‘development’ in the very essence of human beingness that could transform art from the inside out?

Right now, the elephant in the room is: I won’t mention any names but its initials are AI. It’s ironic that one prompts (uses language) to get a rise out of it, at least for now. This current phase is, relatively speaking, neither here nor there. Perhaps when AGI and ASI emerge is when art (and life [and death]) profoundly change. I have no choice but to look forward to it.

FA: In the early 1970s, you spoke of video as “the medium closest to thought.” Is that still the case, or has something changed with the advent of new technologies?

GH: I would correct myself and say that writing is closest to thought, and yes, video is a kind of writing, or at least it can be. On the other hand, using the real-time aspect of video, it can short-circuit language akin to arcing electricity and create a kind of visceral thinking.

FA: You have exhibited many times in Italy, collaborated with Galleria Lia Rumma, and on several occasions conceived site-specific works in dialogue with our artistic and architectural heritage. How would you describe your relationship with Italy?

GH: Dynamic, an intricate tapestry of relationships and experiences.

If memory still serves, the first exhibition in Italy was at the 1995 Venice Biennale, where Withershins was installed. During the week of installation, it poured rain, and a large part of the piece was flooded, including wiring and the switch mats used for triggering the spoken texts. It was catastrophic. When discussing what could be done, the event organizers said, “Well, we’re all in the same boat.” Indeed. Nevertheless, the work was somehow completed for the opening. That was followed by the first of four solo exhibitions with the Lia Rumma Gallery in Naples (where a different way people drive cars was learned!). Learning Curve (still point), 1993, and Clover, 1994, were installed. In 2000, there was an artist-in-residence at the American Academy in Rome. A difficult bout with depression occurred, and a Freudian psychiatrist was seen twice a week for the remainder of the stay. Somehow, Goats & Sheep, 1995/2002, was still made. Concurrently, Wall Piece ended up in the 49th Venice Biennale, but not until after a long train ride with the curator, Harald Szeemann. A visit was made to the CEO of United Colors of Benetton looking for project funding—whom we failed to convince.

In 2005, I quickly learned about the hidden tentacles of politics surrounding the Colosseum, where the installation Resounding Arches was exhibited, and an elaborate performance, Dark Resonances, was done with several collaborators. Coinciding with the last exhibition, Ghost Chance, at the Naples gallery of Lia Rumma, I made an artist book, Inasmuch as It Has Already Taken Place commissioned by the writer Gabriel Guercio and Juxta Press for a project entitled Afterlife. Unfortunately, a planned exhibition of the works was canceled due to Covid.

Perhaps the strangest experience I had in Italy was walking into the Real Bosco di Capodimonte Museum in Naples and seeing a wire sculpture I had made in 1967(?). It was originally commissioned by Marshal Backlar, the producer of the skateboard film Skater Dater which I was in. Still, to this day, I have no idea how or why it was in that museum.

All in all, a wild Italian ride…

FA: Have you had the opportunity to follow the evolution of Italian video art? Are there any Italian artists working with video (or other expressive media) with whom you feel a sense of affinity?

GH: No. Hard to keep up with evolutions of any kind including my own! The good news is I will get a crash course at the Over the Real and Ibrida Festivals and I’m very much looking forward to it.

Cover: Gary Hill, SELF B, 2016 | Courtesy the artist and James Harris Gallery