English version below

Il gioco fa parte della vita di ognuno di noi, in ogni parte del mondo e in ogni contesto sociale e culturale. Guardare il mondo con gli occhi dei bambini, attraverso le regole e i meccanismi del gioco, è ciò che esplora Francis Alÿs nel suo progetto per il Padiglione del Belgio a Biennale Arte 2022, dal titolo The Nature of the Game. A cura di Hilde Teerlinck, lo spazio espositivo del padiglione si trasforma in un grande terreno di gioco, animato da dipinti e film, per lo più inediti. Colti dallo sguardo della videocamera, durante le passeggiate di Alÿs in diversi contesti urbani, i giochi dei bambini diventano metafora di un microcosmo sociale in cui si intrecciano relazioni e punti di vista. La curatrice Hilde Teerlinck ha raccontato in anteprima gli aspetti peculiari del progetto The Nature of the Game e del percorso creativo e artistico di Francis Alÿs.

Veronica Pillon: Francis Alÿs è il protagonista del Padiglione del Belgio di questa edizione di Biennale Arte. Nel corso della sua ricerca, ha esplorato diversi temi – la relazione tra il corpo e lo spazio, il mito di Sisifo, la parata – ma vi siete concentrati sul gioco. “The Nature of the Game” è anche il titolo di questo progetto: che significato ha il gioco per Francis Alÿs?

Hilde Teerlinck: La trama e i processi di molti progetti di Francis sono direttamente ispirati dai giochi dei bambini, nella la natura stessa del gioco, ma anche nelle meccaniche e nell’insieme di regole rigorose e non scritte. Non serve dire nulla ma nel momento in cui si esce dal gioco tutti i bambini obietteranno all’istante.

Francis Alÿs: Lo stesso accade con i miei progetti, non sarei in grado di spiegare chiaramente la trama ma mi è chiaro inmediatamente se sto valicando i confini della mia idea iniziale.

HT: Francis è interessato anche al significato o al messaggio nascosto nel gioco, alla componente della rappresentazione sociale. Spesso ironizza su quest’aspetto ma, allo stesso tempo, fa parte di un lungo processo di assimilazione. A tal proposito, l’antropologo McDougall scrive: “Nelle due decadi passate, gli antropologi hanno iniziato a riconoscere un contributo, economico e culturale, importantissimo ai bambini, in grado di generare un cambiamento sociale. Inoltre, oggi si pone maggiore attenzione all’autonomia dei bambini e alle loro esperienze di vita. Sono considerati di giorno in giorno più indipendenti, esseri umani con propri costumi, credenze e valori”. Continua: “L’intera produzione di Alÿs guarda ai rituali che i bambini mettono in scena. Molti di questi rituali enfatizzano la persistenza e la ripetizione, spettacolo di chi vive ai margini e alla periferia della società”.

VP: Quali sono le implicazioni politiche e sociali del gioco?

HT: Il gioco dei bambini è stato considerato come una relazione creativa con il mondo che li circonda, rivelando una dimensione geo- e sociopolitica, antropologica ed etnologica. Direi che spetta allo spettatore ritrovarla.

VP: Come avete pensato al progetto “The Nature of the Game”?

HT: La procedura di selezione si è svolta in due fasi. Nella prima, la giuria ha invitato sei curatori, tra cui io, a presentare un progetto espositivo per il padiglione Belga alla Biennale di Venezia. Nella seconda fase, dopo la presentazione di ciascun progetto, la giuria ha scelto il vincitore, il 12 giugno 2020. Io avevo invitato Francis e abbiamo lavorato fianco a fianco per sviluppare insieme la proposta per la giuria.

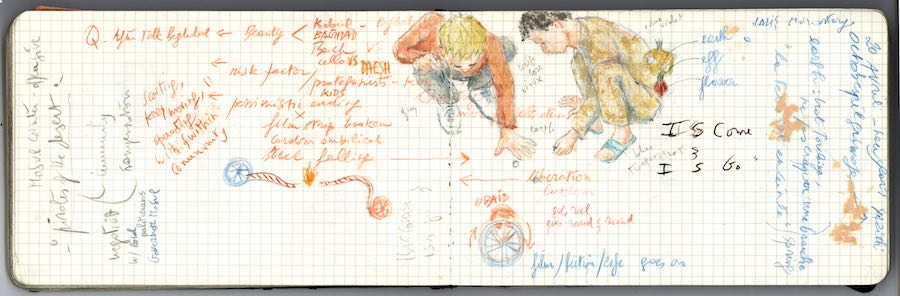

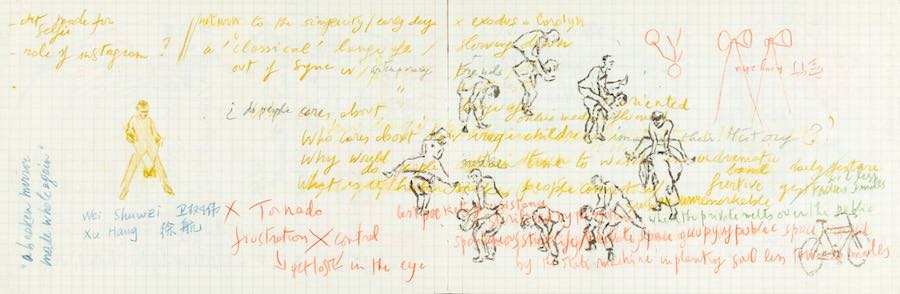

Abbiamo deciso di focalizzarci sul tema del gioco e questa è stata la naturale evoluzione del progetto. Negli ultimi tempi, il lavoro di Francis si è concentrato sul gioco, così abbiamo pensato che anche il progetto del Padiglione dovesse riflettere su questo tema. Questo aspetto particolare della sua ricerca è cominciato nel 1999, quando ha casualmente filmato un bambino mentre calciava una bottiglia in strada, in Messico. Ogni volta che Francis è stato invitato a lavorare in qualche parte del mondo per una mostra o una conferenza, lui ha sempre camminato per strada (osservare le persone nello spazio urbano è una costante del suo lavoro) e ha cominciato a filmare i bambini mentre giocavano. In questo modo ha scoperto e capito (o almeno cercato di capire!) la società, la cultura e il comportamento della comunità. Di fatto non c’è uno schema, ma segue ciò che accade intorno a lui.

Negli ultimi vent’anni di carriera, la sua collezione di “children’s games” è cresciuta. Francis ha scoperto che alcuni giochi sono praticati in tutto il mondo, conferendone un carattere universale. Altri invece appartengono ad una certa regione o cultura.

Ad aprile 2021, quando abbiamo visitato Venezia, abbiamo deciso di dedicare il padiglione al tema del gioco. Francis ha notato che i bambini non giocano più così tanto all’aperto e negli spazi pubblici: è necessario che qualcuno glielo ricordi. L’interazione sociale faccia a faccia si sta trasformando in qualcosa di virtuale, un fenomeno che si è ulteriormente sviluppato con la pandemia. La stessa architettura del padiglione l’ha ispirato a trasformarlo in un grande campo da gioco con 14 film.

VP: Alÿs vive in Messico, ma ha spesso lavorato in zone di guerra, luoghi in cui ha documentato la vita quotidiana attraverso la videocamera. In questa esposizione propone sia dei dipinti che dei video, ma sono quest’ultimi i veri protagonisti. Nei film si concentra sull’infanzia: qual è la relazione tra il mondo dei bambini e quello degli adulti?

HT: Nel padiglione ci saranno 14 video e 16 film, che, usando le parole di Francis, sono “complementari, come le geste et l’image”.

I film sono stati prodotti da poco e alcuni sono ancora in produzione e post-produzione. I dipinti offrono, dall’altro lato, ciò che Alÿs definisce “recorrido de mi trabajo”. “Recorrido” implica un viaggio e una durata più lunga, forse potremmo considerarla una “corsa”?

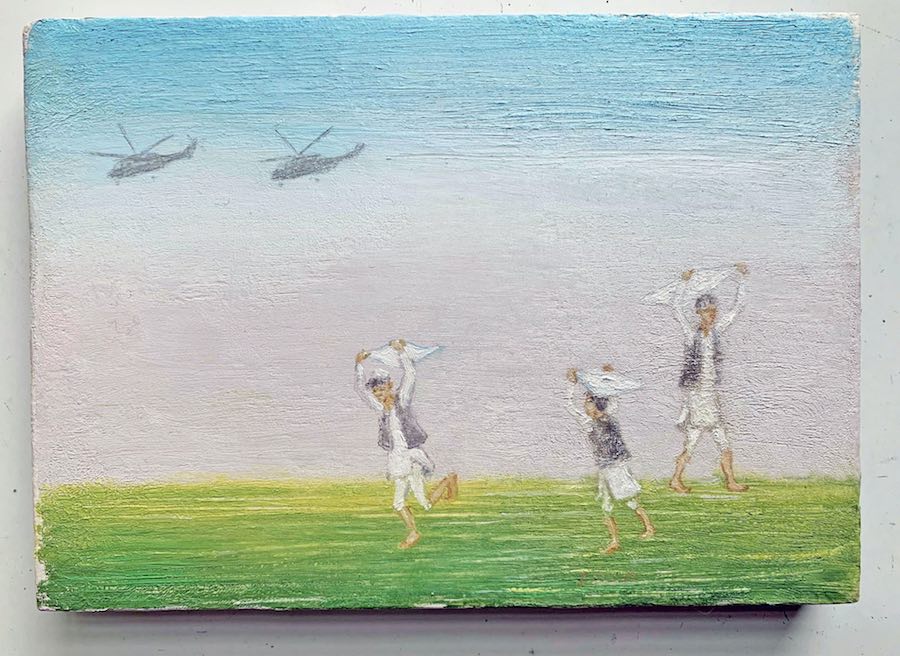

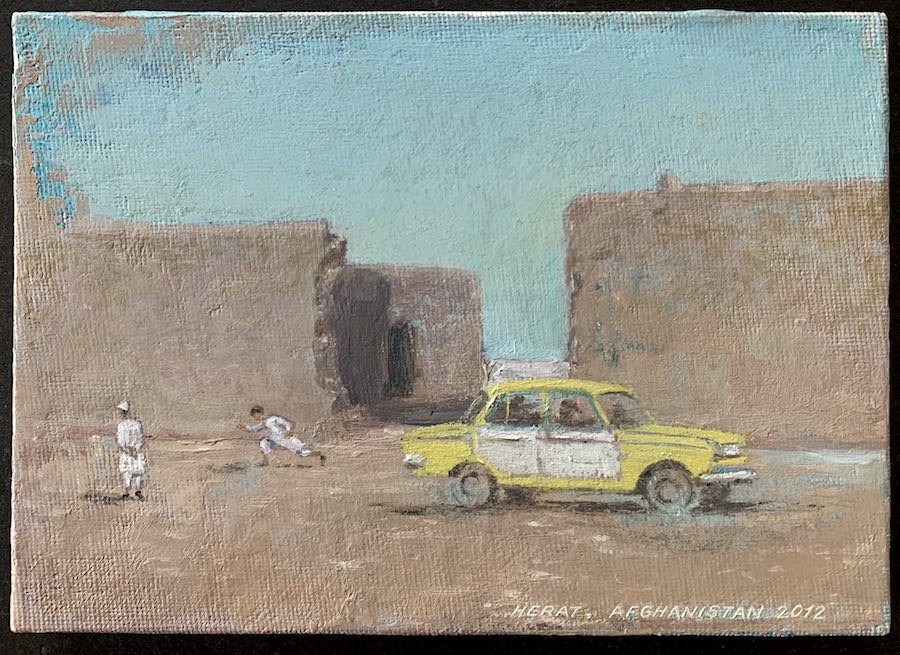

Lui ha sempre ripreso i bambini giocare quando lavorava. Ha spesso lavorato in zone di guerra e ha sviluppato un corpus di opere sul tema. I due temi sono di fatto legati: se gli adulti prediligono l’uso della parola per processare un trauma, il gioco aiuta i bambini a superare un trauma, come la guerra. I bambini giocano per esprimere i loro sentimenti: in questo modo trovano un senso alla realtà circostante, anche nelle situazioni più violente. Giocando, il bambino trasforma il trauma provocato dal conflitto armato in controllo. Questo ha un effetto curativo o per lo meno li aiuta ad adattarsi alle circostanze.

In maniera sfacciatamente onesta, Francis pone una questione fondamentale: qual è il ruolo e la rilevanza dell’artista in situazioni di conflitto e crisi?

VP: Qual è il legame tra “The Nature of the Game” e “The Milk of Dreams”, titolo della mostra scelto da Cecilia Alemani per Biennale, che parla di “Rinascimento” e “cambiamento”?

HT: In realtà abbiamo cominciato a lavorare al progetto due anni fa, quando il tema non era ancora stato annunciato.

Biennale 2022 | Interview with Hilde Teerlinck, curator of the Belgian Pavilion

Veronica Pillon: Francis Alÿs is the protagonist of Belgian Pavillon for this edition of Biennale Arte. He explored different themes with his artistic research – the relationship between body and space, the Sisyphean myth, the parade – but you have focused on gaming. “The Nature of the Game” is also the title of this project: what does the game mean for Alÿs?

Hilde Teerlinck: The scripts and processes of a lot of Francis’ projects are directly inspired by children’s games; the nature of the game itself, but also the mechanics and set of rigorous unspoken rules – nothing is said but the second you step out of the game, all of the children will instantly object.

Francis Alÿs: “The same happens with my projects, I would not be able to clearly articulate their plot but it’s always crystal clear to me when I am stepping out of bounds with my initial intention.”

HT: Francis is also interested in the hidden meaning or message of games, the component of social representation, often mocking it but also being part of a slow process of assimilation. Anthropologist McDougall writes in the text of the publication: “In the past two decades anthropologists have come to recognise that children make important economic and cultural contributions to society and may be significant generators of social change. Moreover, greater attention is now being paid to the autonomy of children and their life experiences. They are increasingly seen as independent beings with their own customs, beliefs, and values.”

“The whole of Alÿs’s art resonates with the themes found in the rituals that children perform. Many of these emphasize persistence and repetition, as well as the spectacle of an outsider on the periphery of society.”

VP: Which are the social and political implications in it?

HT: Children’s play is to be understood as a creative relationship with the world in which they are living, revealing a socio-political, geo-political, anthropological, ethnological dimension. I would say that it’s up to the viewer to fill this in.

VP: How did you and Alÿs design “The Nature of the Game”?

HT: The selection procedure was held in two phases. In the first phase, the jury invited six curators – I was amongst them – to present an exhibition project for the Belgian Pavilion in Venice. In the second phase, and after the presentation of each project, the jury made the final decision on June 12, 2020. I invited Francis and we worked closely together to develop the proposal for the jury.

We decided to focus on children’s games and this was actually the consequence of an evolution in the project. Recently, children’s games took up a central position in Francis’ work so we decided that the Pavilion should reflect this. He began in 1999 coincidentally filming a boy who played with a bottle in the streets of Mexico. Each time Francis was invited to work somewhere in the world to put on an exhibition, or to give a conference, he walked through the streets (observing the people in an urban space is a constant in the work of his) and started to film children playing. It was a way for him to discover and to understand (or, try to understand) the society, the culture, the behavior of a community. So, there is no masterplan. He just goes with the flow.

Over the last 20 years, his collection of children’s games has grown. He discovered that some games are played all over the world, thus giving it a universal character. Others are related to a certain region or culture.

When visiting Venice in April last year, we decided that the Pavilion should be dedicated to the children’s games. Francis noticed that children don’t play so much in public spaces anymore, so, there is a new urgency to record them. Face-to-face social interaction is becoming more and more virtual , a phenomena recently accentuated by the pandemic. It was also the architecture of the Pavilion that inspired him to transform it into one big playground with around 14 films.

VP: He lives in Mexico, but he has often worked in war zones using his camera to document everyday life: in this exhibition, he proposes some paintings, but the films are the real protagonists. In them, he always focuses on childhood: what is the relationship between children’s world and that of adults?

HT: There will be around 14 videos and around 16 paintings. In Francis’ words, both are complementary, it’s like “le geste et l’image”.

The films were produced quite recently and some are still in production and post-production at the moment. The paintings on the other hand offer a much larger “recorrido de mi trabajo” as Francis likes to call it. “Recorrido” implies a journey and a longer span of time, so maybe in English we could say a “ride”?

He has always recorded children’s games in different parts of the world where he has worked. Francis has often worked in warzones and has developed a body of work around it. The two are actually closely linked: Whilst adults are more likely to use language to help process trauma, play helps children cope with trauma, like war in this instance. Children play to express their feelings. It is a way they make sense of their reality, even in the most violent of circumstances. By playing, children can transform trauma provoked by armed conflict into feelings of control. This can help them find healing, or help them adapt to a change in circumstances.

In a devastatingly honest way, Francis postulates often an essential question: what is the role and the relevance of the artist in situations of conflicts and crisis?

VP: What is the link between “The Nature of the Game” and “The Milk of Dreams”, the title chosen by Cecilia Alemani for Biennale, focused on “Reinassance” and changes?

HT: We started to work on the exhibition for the Pavilion two years ago when the theme of the exhibition curated by Cecilia Alemani hadn’t been announced yet.

Padiglione del Belgio alla 59. Esposizione Internazionale d’Arte – La Biennale di Venezia

The Nature of the Game | Francis Alÿs

Curato da Hilde Teerlinck

Commissario: Jan Jambon, Ministro-Presidente del Governo delle Fiandre e Ministro Fiammingo degli Affari Esteri, della Cultura, della Digitalizzazione e della Gestione delle Risorse

Dal 23 aprile al 27 novembre 2022