Dedicated to artistic experimentation and collaboration Mimosa House (12 Princes street, W1B 2LL, London) is a new, independent, non-profit project space in the heart of Mayfair that works with emerging practitioners. Developed by curator Daria Khan, Mimosa House supports artistic process and exchange and delivers a public programme including four group exhibitions a year and collateral events. The programme will focus on self-initiated artists’ projects and collaborations by female and queer artists in particular.

The space opens with a new project. The exhibition Growing Gills is conceived by artists Joana Escoval and Gaia Fugazza, writer Agnieszka Gratza, curator Daria Khan and photographer Giovanna Silva.

Agnieszka Gratza: As a sculptor, you tend to work with raw materials that you find in nature only to then put them back – as if you had them out on loan – by displaying the artworks you’ve turned them into outdoors, there to be weathered and gradually reclaimed by nature. Would you say nature – by which I mean plants, animals, the elements, and so forth – is your intended audience? and is that a form of animism?

Joana Escoval: It’s not so much that I work with raw materials but with matter(s) that are in transformation, mutation. I’ve been working more and more with different precious metals and alloys, materials one can argue are actually raw but never found as such in nature. So, in this sense, I feel I’m more an heiress to an alchemic tradition that today takes place not in the laboratories and cauldrons of the past but between the studio and the outdoors. The audience is, therefore, not exactly what we tend to call nature, but we as players within that ‘nature’, within a transformational sphere.

To try and answer your question about a sort of animism, I’d like to avoid drawing up hierarchies between myself, my works and other beings like plants and animals. When mined, metals are usually found as parts of certain geological / chemical compounds, they are in composition with others. I feel that there is a certain truth to the archaic idea of aether: even solid states, let alone other states of matter, are inter-related, ‘spirited’ with energies and vibrations.

Daria Khan: Your works for Growing Gills revolve around the use of psychedelic plants in the witchcraft tradition. Which historical facts and which direct experiences had an impact on your works?

Gaia Fugazza: My fascination with psychedelic plants extends to the broader context around their ceremonial and healing uses. When I first encountered ayahuasca, despite having a beautiful experience with it, I was disturbed by the commerce and the spiritual tourism surrounding it. Since every region has its own indigenous plants, I took to studying how psychotropic plants have traditionally been used in the Mediterranean. This is how I came across ‘witch’ potions.

The label ‘witch’ was given to a woman practising herbal medicine, a spiritual healer or just a free person in touch with nature and using her body as a bridge between the natural worlds the and the village. These women and their knowledge have been discredited by Christianity, modern medicine and scientific thought. Urbanisation and a change in traditions have wiped out the few remnants of animist spiritual worlds present in people’s daily lives. Aside from the drama of the ‘witch hunt’, a lot of knowledge and practices were lost with it.

The works I produced for Growing Gills are homages to plants found in Europe such as datura stramonium, atropa belladonna (both present in the ‘Potion to Fly’) or ipomea violacea (whose seeds contain LSA, a molecule similar to LSD).

Gaia Fugazza: In your volcanic swims, you seem to resist basic planning and props, so that relatively straightforward actions became potentially harmful (swimming in jellyfish-infested waters, in a sulphurous lake with pH0, alongside the Sciara del Fuoco, a continually erupting volcano…). Is this a peculiar case of distraction or are you purposely tempting fate and asking the environment to leave a mark on you?

Agnieszka Gratza: Your question makes me sound either rash or suicidal. I’m neither, really. Too much planning can take the fun out of things and I’ve always had an aversion for anything that counts as ‘equipment’. Volcanic swimming for me is an aesthetic pursuit and a meditative activity, rather than a sport. I remember once reading somewhere that all you needed to swim is a towel and a bathing suit (and even that is optional). That said, there’s nothing ‘straightforward’ about these ‘actions’, as you say. Swimming is dangerous in and of itself and the volcanic setting undeniably compounds that.

The element of risk involved may be part of the appeal of volcanic swimming – a way of living life more intensely or defying death. Many of the places I have swam in around the world since this project began two and a half years ago are hard to access and sometimes off-bounds. Volcanic swims are forbidden pleasures that you indulge in at your own peril.

Documenting these swims, in writing or otherwise, has not been my primary concern so far. I’m building up a collection of volcanic swims, as and when the opportunities arise, one which is inscribed in my body.

Joana Escoval: You told me about about running and how you’ve been preparing yourself for marathons. What’s the sound in your head like when you run and when you decide to start a new book in collaboration with someone, as a publisher and photographer? In this case, do words matter?

Giovanna Silva: I run, I swim, and the only way to survive is by listening to music. I have four waterproof mp3, each one with a different playlist, from romantic Italian songs to electronic music. Once I swam for one hour listening to the same song (Jim O’Rourke Women of the World) in repeat. And while I’m running I prefer to listen to podcasts or audiobooks.

In my work as a photographer and publisher, words are important, at least for a title. I published a book about discotheques titled Nightswimming (but not because of the R.E.M. song) and one about Egypt whose title is Walk like an Egyptian (yes, because of The Bangles’ song).

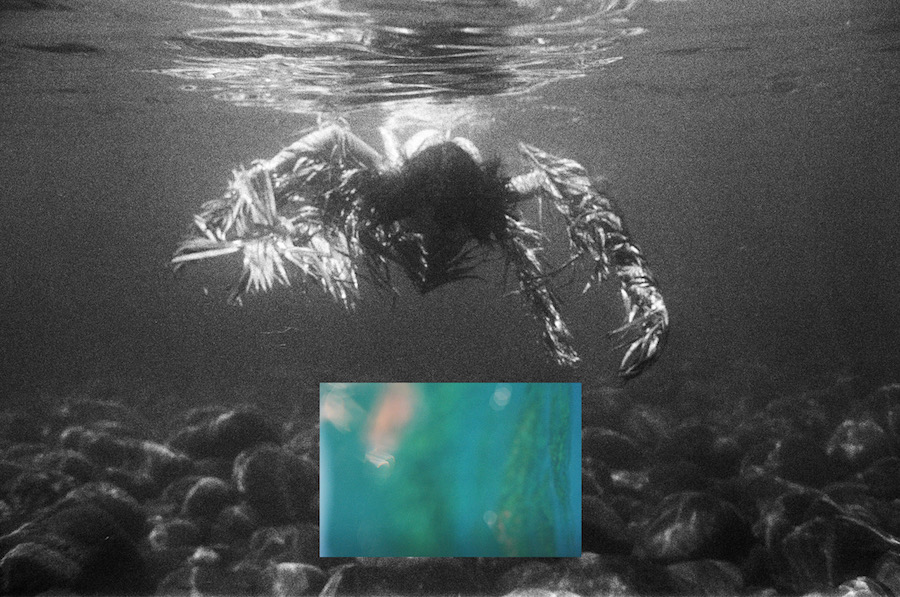

After reading Haunts of The Black Masseur, by Charles Sprawson – a beautiful non-fiction book about great swimming heroes, from Byron to Leander – I became obsessed with the idea of the sea and long-distance swimming. I bought a Nikonos, a 1980s analogue waterproof camera, and I started taking pictures from the coast – sometimes a rock, sometimes a crowded beach – from the sea level.

Giovanna Silva: As Curator and Founder at Mimosa House, how was it to be part of this adventure? You were there with us, literally living this project, physically part of it. You where more than a curator in Stromboli…

Daria Khan: The whole adventure happened in a very spontaneous way – Gaia told me about the residency you were planning and the subjects you were planning to explore, such as volcanic swimming, experiments with altered states, etc. At the time I was already planning the exhibition programme for Mimosa House, so I thought about joining the residency and seeing if we could then show something that came out of it at Mimosa House.

The experience was physical indeed: I joined the five-hour walk up to the craters of the active volcano, practised volcanic swimming, read texts selected by Agnieszka on the subject of travel to the centre of the earth, participated in the drumming meditation session, visited the local nursery to learn about plants and their use in spiritual ceremonies, as well as about witches. I was fully part of the dialogue which took place during the residency, and I’m excited to see how this experience we all shared will translate into an exhibition.

I was really curious about how self-initiated artists’ projects work, and in this case I had to withdraw myself as curator, so as to join the process which was already in formation, choosing the position of an equal participant.

And in relation to what you were saying about long-distance swimming heroes – it makes me think about a quote from The Descent of Woman by Elaine Morgan, in which she states that humanity originates from aquatic apes. She, in her turn quotes Lionel Tiger’s Men in groups: ‘Ironically, the only sport in which females are superior to males is long-distance swimming – a precisely inappropriate skill for a terrestrial mammal’.